“The three finest things God ever made,” wrote Gustave Flaubert in 1846, “are the

sea,

Hamlet, and Mozart’s

Don Giovanni.” Less pithy but no less ardent about

Don Giovanni’s canonic status was another Frenchman, the composer Charles Gounod, who described

the opera as “a luminous apparition, a kind of revelatory vision” that embraced “the

beautiful and the terrible,” combining “truth of expression” and “perfect beauty.”

This was a work of art, Gounod believed, “to which the centuries must pay homage.”

It is, to be sure, the most perfect fusion of tragedy and comedy in all of opera,

though this duality—evident right from the overture, shifting suddenly from a dark,

formidable D minor to a bright and spritely D major—suggests a few interpretive possibilities.

Do you approach the piece primarily as a tragedy injected with comic relief (as the

legendary conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler did)? Or as a comedy that happens to contain

some grave scenes, remembering that Mozart himself classified

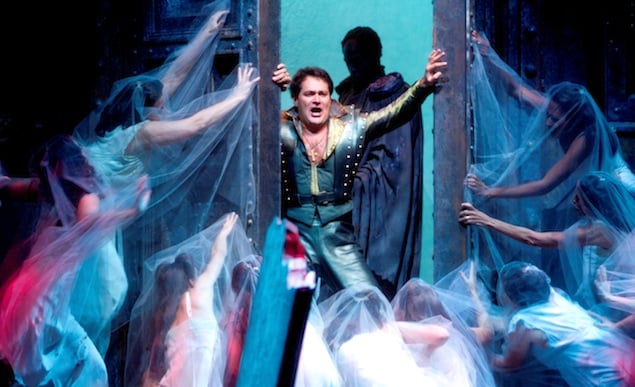

Don Giovanni as an opera buffa? The Washington National Opera’s revival of director

John Pascoe’s production takes the latter approach. And though the premiere last Thursday night

was successful and assured, it did seem to lack some power, largely because the work’s

darker elements were glossed over.

This isn’t to suggest that bass

Ildar Abdrazakov lacks the heft required to play Don Giovanni; on the contrary, he has a big, sonorous

voice (that’s equally sweet-toned and lyrical), and he has enough charisma to play

the classic rake, a character at once seductive, cruel, alluring, and selfish, interested

only in a life of wine, women, and yet more women. Yet in general, he was a gentler,

more humane Giovanni. Upon killing the Commendatore in the duel that opens the work,

for example, he is compassionate toward his fallen foe. And when the Don later woos

the peasant girl Zerlina in the famous duet “Là ci darem la mano,” the tone Abdrazakov

produced in the gentlest, quietest passages was exquisite—you really could understand

how Zerlina, on her wedding day of all days, could fall for him.

Perhaps the only place Abdrazakov faltered was in the famous “Champagne Aria”—“Fin

ch’han dal vino”—where he wasn’t quite agile enough to negotiate the rapid passagework.

The agility Mozart calls for here isn’t mere virtuosity. The Don, after all, is constantly

eluding women, escaping tricky situations, and having to think fast to outwit those

who wish to hunt him down, and the brisk and nimble qualities of this music are emblematic

of his character.

But does it matter that Abdrazakov’s Don isn’t the sort of relentlessly cruel and

violent character that other basses have portrayed in the past?

One of the ironies of

Don Giovanni is that even though the title character is in constant pursuit of sexual conquest,

he spends the duration of the opera on the run, being pursued by others: by Donna

Anna and Don Ottavio, who seek to avenge the Commendatore’s death; by the tortured

Donna Elvira, who offers Giovanni redemption through the promise of her love; and

by the dead Commendatore himself, whose shade manifests itself as the statue that

comes to dinner at the opera’s end. It is responsibility, as well, from which Giovanni

flees—responsibility for the crimes he’s committed, for the women he’s bedded and

abandoned. His philosophy is the ultimate expression of freedom: to live outside the

moral and legal bounds of a society, without anything resembling a conscience. He’s

the consummate rebel—brazen sexuality being the instrument of his rebellion—and he

demands a slightly darker characterization, as a consequence, than what Abdrazakov

gives us.

Of the opera’s three sopranos,

Barbara Frittoli is outstanding as Donna Elvira, conveying anguish, virtue, and anger in a voice that’s

creamy and plush; her second-act “Mi tradì quell’alma ingrate” is a hauntingly beautiful

lament. For my taste,

Meagan Miller’s vibrato is a bit too wide, her sound somewhat metallic in the upper register, though

she’s appropriately intense as the vengeful Donna Anna.

Veronica Cangemi is a monochromatic Zerlina, though she’s best in the second act when she consoles

her beaten-up fiancé, Masetto (sung with appealing menace by baritone

Aleksey Bogdanov), her darker tone here giving the character both richness and depth.

Andrew Foster-Williams is excellent as the Don’s cowardly servant, Leporello, ironic and playful in the

first act, full of bravura in the second; and

Soloman Howard is powerful as the Commendatore.

Juan Francisco Gatell sings an impassioned Don Ottavio, phrasing the long arching lines of his Act I “Della

sua pace”—one of the most sublime numbers in a work composed of one sublime number

after another—with elegance.

Overall, this is a well-sung

Don Giovanni, though in a few instances, Mozart’s heavenly music is compromised by bits of silly

stage direction. Cangemi’s lovely “Vedrai, carino” is nearly spoiled by the sight

of Bogdanov crawling and slithering across the stage after her. And for me, there’s

nothing sexual about Zerlina’s moving, guilt-ridden “Batti, batti, o bel Masetto,”

but there is Cangemi bending over, coquettishly asking Bogdanov to spank her. There’s

comedy enough in the text to make any added slapstick a distraction. And when the

music and the action get deadly serious later in the piece, the audience is still,

unfortunately, in the mood to laugh—an unintended consequence of hamming up the comedy

at the expense of the work’s abiding darkness.

This is never an issue with the orchestra. After some spotty work in Donizetti’s

Anna Bolena less than a week before, the musicians play with great power

and finesse, conductor

Philippe Auguin leading a magnificent performance, old-fashioned and red-blooded. In the gripping

banquet scene, when the Commendatore’s statue condemns Don Giovanni to hell, the orchestra

is the star, unleashing torrents of roiling music, the scales rising and falling menacingly

as the Don, unrepentant to the last, finally meets his end.

Don Giovanni

is at the Kennedy Center Opera House through October 13. Running time is around three

hours and 15 minutes. Tickets ($25 to $300) are available via the Kennedy Center’s

website. The performance on October 13 will feature singers

from the Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Program.