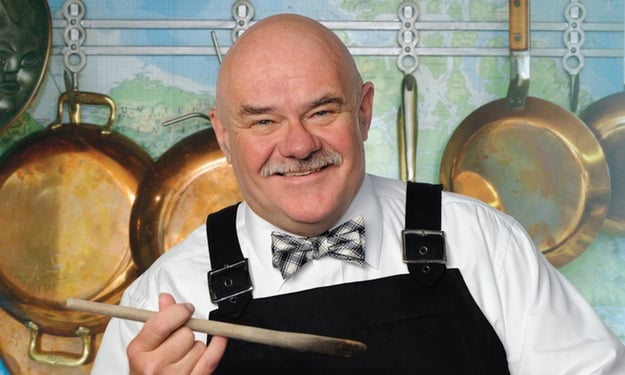

Written by James Still and directed by Leon Major, the one-man play I Love to Eat stars Nick Olcott, who is perhaps best known as a director of theater and opera. A multiple Helen Hayes Award nominee, he currently serves as the interim director of the Opera Studio at the University of Maryland.

For this production, Nick has let his audience in on his preparation for the role, sharing with us the books he has read and the recipes he has cooked in a thoughtful and witty online journal. You can read 2 of the 16 entries on Round House’s website.

Nick is also a friend, and we connected recently to talk about the jovial Beard’s immense loneliness, American food culture then and now, and the famous JB onion sandwich.

Why a play about James Beard?

The best answer to this question came from a woman about 75 years of age, who told me, “When I married in the mid-’50s, my sister gave me two books: Benjamin Spock and James Beard. Those two guys got me through a marriage and four kids.” Dr. Spock reared a generation of Americans; James Beard fed several. He was also a funny, fascinating, and complex individual.

And why Beard and not, say, other large-bodied gastronomes such as Paul Prudhomme or Escoffier?

Ah, for that you must ask the playwright. These men are probably worthy of dramatic portraits, too, but it was playwright James Still’s version of James Beard that fell into my lap and lit my imagination on fire.

Talk to me a little bit about your research. What did you read to gain insights into Beard’s life? What kitchens did you tour? Did you work your way through Beard’s books?

My major resource has been Robert Clark’s excellent biography, The Solace of Food. Mr. Beard’s own “memoir with recipes,” Delights and Prejudices, was also very helpful, even though, like most memoirs, it gives us a better picture of how he wanted to be seen than how he was. The compilation of his letters to Helen Evans Brown, Love and Kisses and a Halo of Truffles, was useful in giving a glimpse of the private man, since not all of the letters were intended for publication.

I have been in restaurant kitchens and have some insight into life there, but I did not do that as part of my research. Mr. Beard’s food life was not really that of a restaurant chef. He served as a consultant for many restaurants, but he only ran a restaurant kitchen once, when he and friends opened Chez Lucky Pierre on Nantucket in 1953. By all accounts, he hated the experience.

Mr. Beard’s true milieu was the dinner party at home. He gave and attended them by the hundreds. His books focus on cooking for family and friends, not on restaurant food. While he definitely championed other restaurant chefs, and his foundation does so still, his real concern was home cooking. And teaching. He was much more comfortable conducting a cooking class in his own kitchen than running a restaurant.

There was no way to work my way through his books; there are too many of them. I decided to approach his food chronologically, in the order he encountered it. I started with what he grew up with: fresh seafood. I made his mother’s clam chowder, steamed clams, and grilled scallops. I made vegetables according the recipes he attributes to people who supplied or worked in her boarding house kitchen: her Italian greengrocer (Joe) and her Chinese cook (Jue-Let), whom Mr. Beard considered his godfather. I went on to make several of Jue-Let’s recipes, including his wonderful Chinese curry, which had a profound impact on Mr. Beard. I then branched out to recipes that he mentioned as “old-fashioned” or “once common”—things he would have encountered when he first started going to restaurants.

Then after dabbling in the canapés and hors d’oeuvres, where he first made his mark, I moved onto the outdoor cooking books, where he had such a profound impact.

I haven’t had time for the bread yet, but I’m hoping to get there.

What are the two or three details from your research that helped you the most in building your portrayal?

On the positive side are his displays of generosity: the way he helped other cooks find jobs and get published, even when (as in the case of Richard Nelson) it turned out they were plagiarists. Mr. Beard couldn’t see dishonesty or disingenuousness. He had none in himself and couldn’t imagine it in others.

On the negative side are his self-destructive tendencies. Even after heart attacks and embolisms, he would go on Kentucky Fried Chicken binges and eat nothing else for weeks on end. He loved food, but in the end he used it to commit suicide.

Some months back, you mentioned to me the famous JB onion sandwich. Why do you love this “dish”—or, more to the point, what does it tell you about the man?

It’s amazing today to think of this simple hors d’oeuvre attracting so much attention. It’s bread, mayonnaise, onion, and parsley. Period. This got a review in the New York Times? I think we have to look at in the context of the era, when Cheez Whiz on a Ritz was considered a proper canapé. Mr. Beard’s “onion ring,” as he called it, was startling: entirely fresh, entirely raw, entirely bold in taste. It’s easy today to think it commonplace. At the time it was a revelation. And that’s what I think it shows about him. He dared to be simple, dared to be honest.

From a distance, Beard’s life would appear a fortunate one, not to mention a delicious one. How do you create drama out of it?

He cultivated an aura of well-being, but his life was not all that happy. He barely knew his father. He was close with his mother, but she appears to have been something of a tyrant. (Even as he praises her in his memoir, he says, “She was more a manager than a mother.) He was fat and unathletic in the American West. He was thrown out of college for sleeping with a male professor. His dream was to be an opera star, and he failed. Then to be a movie star—and he failed. Then to be a stage actor. He only stumbled on chefdom by accident. He gained fame as a chef, but his television show (the first cooking show on TV) flopped. He never found real love; he had a series of younger lovers who appear either to have been mentally unstable and/or were only using him for his money and fame. While appearing in public as a jovial giant, he was in fact a deeply unhappy and lonely man. Like many great entertainers, he was covering up a lot of pain.

What’s been director Leon Major’s biggest contribution to creating the character of JB?

He’s unlocked a couple of sections of the script for me—passages where I didn’t understand what was going on. He understands the motivation for every moment, and he’s really helped me find my way through it. The biggest of those was showing me how guilty Mr. Beard felt about the endorsements and commercials he did. I hadn’t realized how severely Mr. Beard was plagued by the thought that he had sold out.

Are you a better—or different—cook now, having pored over cookbooks and spent considerable time entering the world of JB?

I used to loathe cooking. Now I really enjoy it. What’s even more amazing: I’m a better eater. I realized that real food, made with fresh ingredients, is so much more satisfying than processed food. I used to have a real weakness for junk food, but the thought of it now makes me slightly queasy. I’ve been eating so much better that I’ve actually lost 15 pounds, even while making recipes full of butter and oil.

Food culture in the US seems drastically different from when Beard was working. Did you envision this show as a comment on that? JB was not telegenic in that slick way we associate with chippy cooking shows, nor was he shticky.

He certainly was not telegenic, and the clips I’ve seen of his appearances on the Today show and of his 1960s Canadian TV show are the opposite of slick. They’re almost painfully slow. The food prep gets done in real time. The emphasis isn’t on the “wow” factor; his presentation is honestly educational. The play makes an oblique swipe at overly elaborate Martha Stewart-type entertaining, and Mr. Beard inveighs in the script against “hotshot” chefs who “mess around and modify” without having mastered the basics. But I’m not sure the play is intended as a commentary on today’s scene. It just enunciates what mattered to Mr. Beard.

Have you been in contact with the Beard Foundation? What help did you get from them?

They provided DVDs of the clips I mentioned above. Both the set designer and director have made pilgrimages to the Beard House in New York and have met with people from the foundation. My schedule hasn’t made that possible for me. But the foundation people have been helpful in every way we’ve asked.

Would you describe yourself as a food lover or even—gasp—a foodie? Someone who, for instance, constructs travel around food or goes far and long in pursuit of great barbecue?

I’ve definitely never been a “foodie,” if that means someone who knows a lot about food. I’ve always been someone who enjoys good food, and restaurants are always an important part of my travel plans. I’ve never chosen to visit a place because of a restaurant, but once I decide to go somewhere, researching the restaurants is a top priority. I remember a trip to Florence in the pre-Internet age where I made reservations at the best restaurants by letter a month in advance to be sure I could get in.

Final, possibly unrelated question: As an actor, what do you think of the famous/infamous stunt around which Ruth Reichl constructed her memoir Garlic and Sapphires —that is, dressing in costume and creating characters to review restaurants?

I read that book and honestly didn’t think a whole lot of it. It defied credibility for me that she really disguised herself so well that no one recognized her. She seemed so incredibly self-involved the whole time that I came away suspecting the only person she fooled was herself.