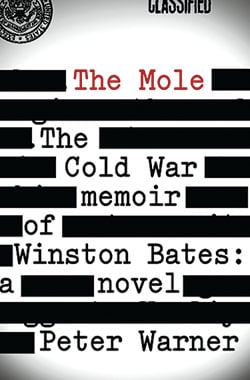

Early in Peter Warner’s crafty post-World War II spy novel,

The Mole: The Cold War Memoir of Winston Bates, Central

Intelligence Agency director Allen Dulles shows Bates a surveillance photo

of the prison where a KGB agent turned CIA operative was likely tortured

and killed. Bates, a Canadian spy working in DC, is the one who pegged the

poor devil as a Western sympathizer.

“I stared at the picture,” Bates says. “I tried to imagine him

in the dark, conspiratorial corners of the Kremlin, risking everything for

a ranch house in Scottsdale.” The moment perfectly captures espionage’s

high stakes and dubious rewards. This is no game for amateurs. At least no

game for most amateurs.

A hapless poet recruited in 1948 Paris during the “happy

interlude between university and serious life,” Bates is armed with little

more than a photographic memory, a taste for high society, and a knack for

finding himself in the right place at the right time. When the novel

opens, it’s 1953 and Bates has maneuvered his way onto Senator Richard

Russell’s staff. Over the next two decades, he’ll rub elbows with the

power elite while intervening in many of the era’s extraordinary events,

from the Suez crisis to Watergate.

Bates emerges as an observant, ruminant agitator. He wonders,

for example, if his Georgetown neighbor, a starry-eyed Pentagon staffer he

finesses, hides “in the past to protect himself from an ever more

demanding present.” Here a young Bates despairs of his literary dreams

after falling victim to a Paris publishing scam: “As my train rattled

across Europe, I mentally cast my poems away, phrase after phrase, leaves

fluttering away into the night that swept past me like a black wind

outside my window.”

Warner, who last published a novel in 1985, knows Washington

intimately, and he particularly nails the way that the right social access

can lead to professional success. But perhaps most impressive is his

informed rendering of the capital’s evolution.

When the novel opens, for example, Bates takes a trolley to

Dupont Circle, and the Georgetown pool is segregated. But by the end, DC

looks entirely familiar to us: “Though expensive, it wasn’t hard to get an

apartment, and a number of the residents seemed to have temporary or

unexpected reasons for living in Washington—foreign businessmen looking

for contacts; journalists on special assignments; diplomatic families

awaiting more permanent housing; and probably the occasional

spy.”

This article appears in the October 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.

Publisher:

Thomas Dunne Books

Price:

$17.07