In 1965, the Beltway was a newborn. Metro didn’t exist. The Mall’s museums were stuffy and formal. The music scene was Dixieland jazz. Tysons Corner was literally a corner. And 14th Street hadn’t even burned in a riot, much less been reborn as a hot dining destination. Here’s the story of how we became us.

1965

The Beltway Rises

These days, I-495 doesn’t get much love. Commuters curse it for gridlock; urbanists blame it for hollowing out the city. In its first full year, though, locals were more focused on how amazing it was to go from McLean to College Park in 30 minutes.

1967

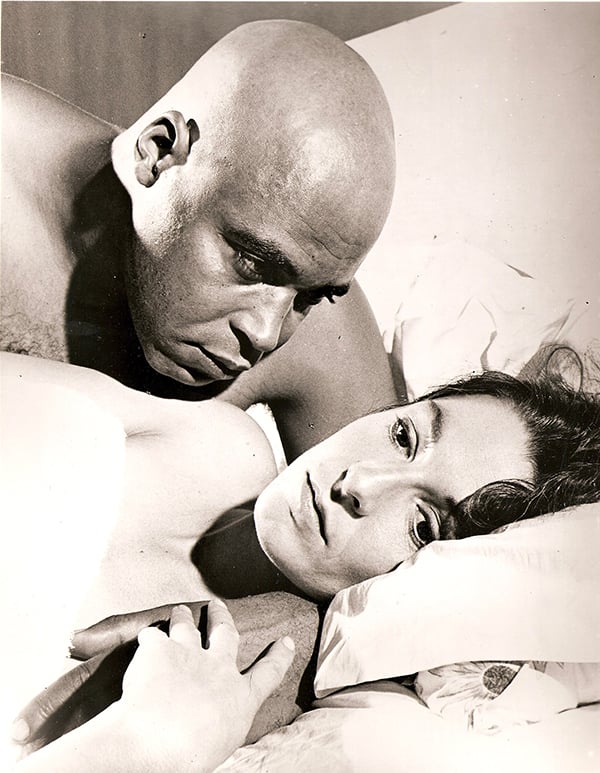

The Great White Hope Debuts

When a newcomer named James Earl Jones took the stage opposite Jane Alexander in a searing drama featuring an interracial relationship, the reaction was so sharp that actors in the show reportedly got death threats. The play–which became one of the first regional-theater works to move to Broadway (winning a Tony and a Pulitzer Prize)–announced the arrival of Arena Stage as a major force in American theater.

1968

DC Burns

For years, Washington remembered the riots that followed Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination as a kind of apocalyptic watershed, hastening white flight and a spiral of civic decline. History, though, has a way of moving on. Forty-odd years later, the center of the turmoil is one of DC’s most vital neighborhoods. So yes, the riots changed everything. But the other lesson is that everything can change again.

1968

Ted Lerner Builds Tysons Corner Center

As late as the 1950s, Tysons was a rural intersection with a couple of small stores. By the end of the next decade, it was home to one of the nation’s largest enclosed malls, an emblem of booming, affluent Fair-fax County. These days, the neighborhood around it is a city of its own. To demonstrate that, in 2012, officials decided to drop “Corner” from its name.

1969

Agronsky & Company Premieres

Before Watergate made heroes of muckrakers, a Channel 9 talk show helped establish a less admirable media archetype: the TV gasbag. Other programs featured reporters, of course, but on Agronsky & Company the entire round-table was composed of them–and a new breed of Washington lecture-circuit celebrity was born.

1970

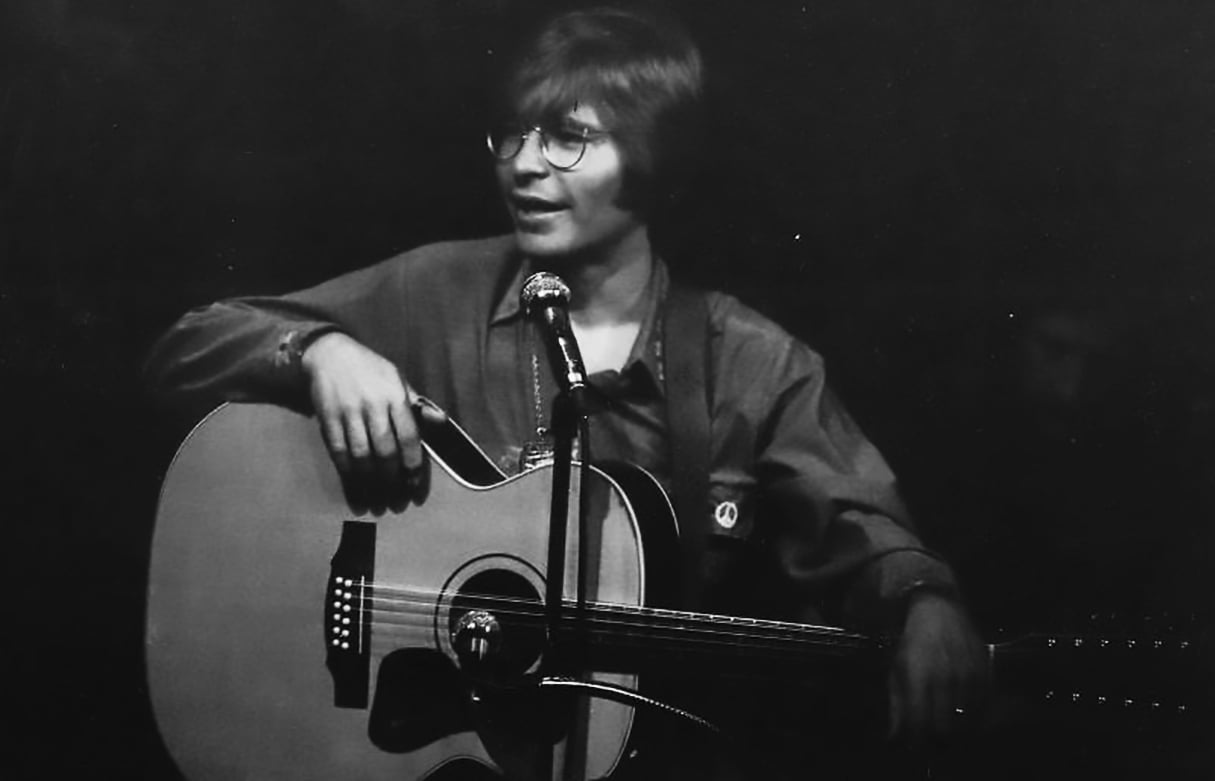

John Denver Plays the Cellar Door

From the 1960s through 1981, Georgetown was home to one of America’s great music clubs. Emmylou Harris hung out there. Neil Young, Linda Ronstadt, Carly Simon, and B.B. King all played there. Miles Davis recorded an album there. But perhaps the venue’s most famous moment was the night John Denver, noodling around with the opening act, Bill and Taffy Danoff, improvised “Take Me Home, Country Roads” (written by the Danoffs) on the club’s stage. Washington then was still Southern enough to have vibrant country and bluegrass scenes. At the Cellar Door, those musicians played alongside stars of the age.

1971

Katharine Graham Okays the Pentagon Papers

When Kay Graham took over the Washington Post, it was the area’s second paper. But within a decade–even before Watergate–it was spoken about in the same breath as the New York Times. One reason was Graham’s decision to back executive editor Ben Bradlee and publish the Pentagon papers–government documents detailing US involvement in Vietnam–which courts had enjoined the Times from doing. To the frustration of critics who thought her too cozy with the powerful, the showdown made Graham a First Amendment hero and helped solidify the Post’s new status. Two years later, she became the first female CEO of a Fortune 500 company.

1972

George Mason Becomes a University

When the University of Virginia’s pokey little extension school in suburban Washington was born after World War II, it had a handful of students in an old elementary-school building. When it finally became a full-fledged four-year institution, it was a sign of how power had shifted in the Old Dominion: Washington-area counties were now able to pony up millions to build the place. Today, GMU has graduate schools, research centers–and a record of having broken DC universities’ monopoly on public-policy expertise.

1972

Hsing-Hsing and Ling-Ling Move In

How did Chinese pandas become so popular that their images adorned Metro Farecards in the capital of the United States? Geopolitics. The bears were a gift to Richard Nixon on his historic visit to Chairman Mao’s China. Back in Washington, they drew vast crowds despite proving to be rather surly creatures. When they died without leaving a cub, they were replaced–and now we can watch the action online via Panda Cam. Locals thrilled to the recent birth of a panda baby. But of course, thanks once again to geopolitics, it’s not really the same. A newly powerful China didn’t give us Mei Xiang and Tian Tian or their offspring. They’re here on loan.

1973

DC Wins Home Rule

After decades of being kicked around by Congress, the District finally won the right to elect the people who raise its taxes and spend its money. It was an incomplete victory–DC’s taxpayers get no voting representation on the Hill, and the city’s budget remains subject to federal veto. Even in those optimistic early days of home rule, activists knew this was an injustice. Savvy political scientists could also have predicted that it would be an excuse–a loophole that still allows local pols, rightly or wrongly, to blame their troubles on Uncle Sam.

1973

Abe Pollin Builds the Capital Centre

When developer Abe Pollin bought the Baltimore Bullets, created the Washington Capitals, and moved both teams into his new saddle-roofed arena in Landover, it helped demonstrate that Redskins-obsessed Washington was more than a one-sport town–no mean feat just two years after the hap-less Senators departed.

1973

The Heritage Foundation Is Born

By 1973, Republicans had run the executive branch for 12 of the previous 20 years. But conservatives were a puny part of the capital’s policy world. A new think tank changed that, creating the governing playbook for the Reagan years–and jump-starting a well-funded galaxy of conservative intellectual organizations that continue to drive Washington’s ideas business.

One innovation: Looking for alternatives to Bill Clinton’s health-reform effort, Heritage Foundation scholars came up with what was, at the time, considered a more free-market alternative. Today we call it Obamacare.

1974

Mormon Temple Opens

“Surrender, Dorothy!” The soaring suburban temple may be closed to non-Mormons, but the land-mark looming over the Beltway is a familiar sight to commuters–and an inspiration for the Oz-obsessed wags who created the area’s most celebrated (alas, long gone) piece of overpass graffiti.

1974

Nixon Resigns

Watergate changed the leadership of the country and made Richard Nixon infamous. But it changed Washington in more prosaic ways, too. After Watergate, reforms instituted new rules about financial disclosure, gift-giving, and slush funds, obliging even relative nobodies to be more careful. And post-Watergate histories turned adversarial outsiders into the capital’s true heroes, luring a generation of would-be Woodwards and Bernsteins to the capital. And why not? When Alan J. Pakula’s movie All the President’s Men debuted at the Kennedy Center two years after Nixon quit, it made the Washington Post reporters and their silver-fox editor look like the most glamorous people in town.

1974

Haile Selassie Is Overthrown

When a Communist regime supplanted a pro-American monarchy 7,000 miles away, thousands of Ethiopians fled–and many wound up in their old ally’s capital. More than a few of the émigrés opened restaurants, introducing Americans to a wholly new cuisine. Today Washington is the center of the Ethiopian diaspora. And scooping up doro wat with injera is a low-budget rite of passage across the region.

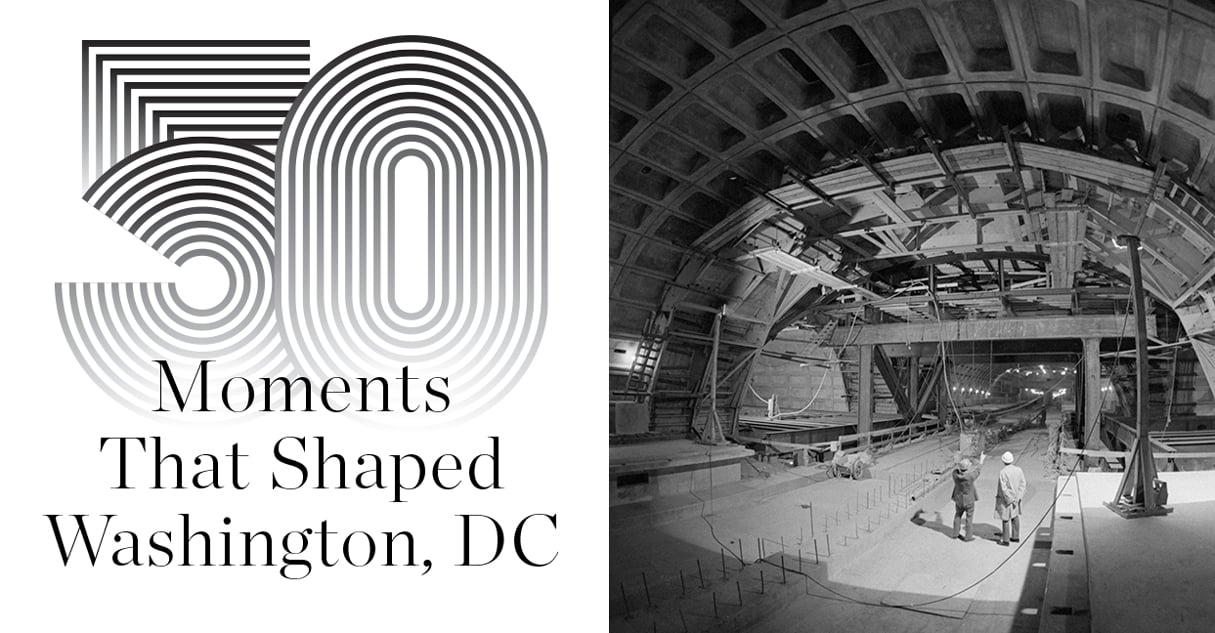

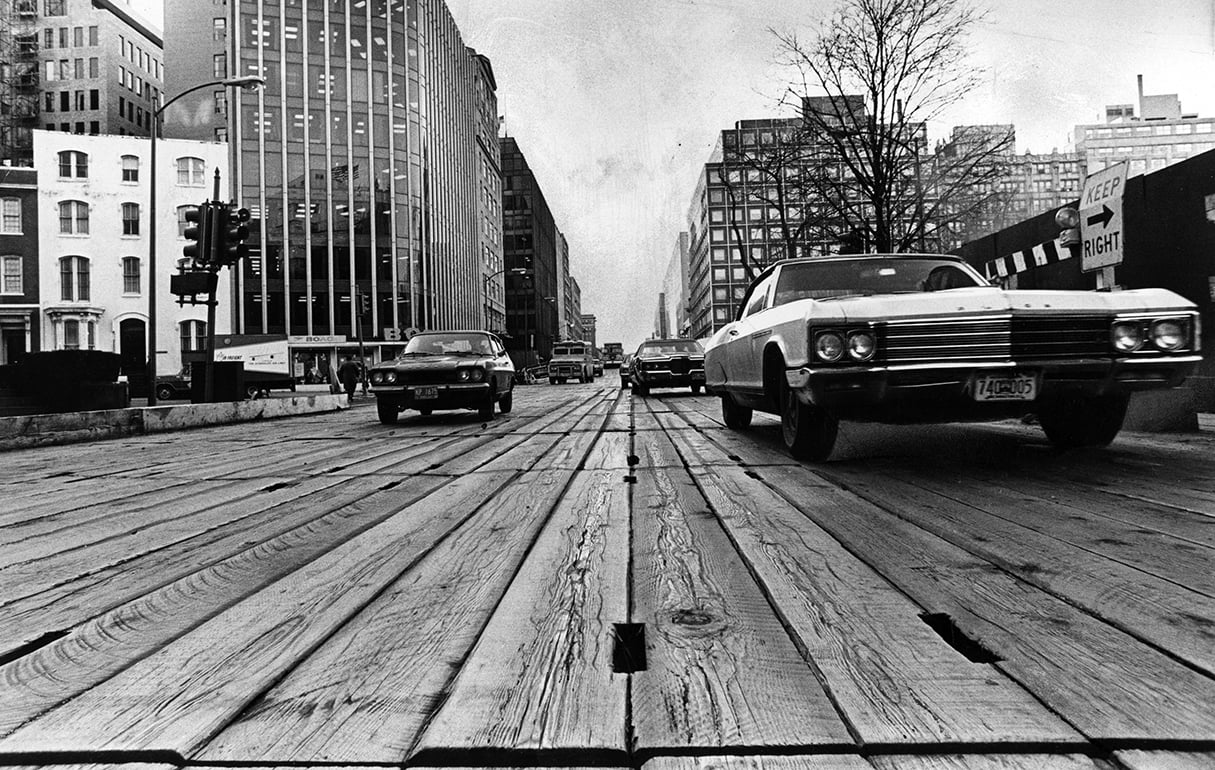

1976

Metro Debuts

After six years of construction-related traffic jams, Metrorail didn’t look like much when it started: five puny stations on the Red Line, all in the District. Even as it expanded across the area, the system’s boosters mainly celebrated pluses like gorgeous stations and spotless cars–not too shabby at a time when New York City’s crime-ridden, graffiti-scarred sub-way seemed like the norm, but not exactly the kind of thing that could alter a region’s trajectory.

That was then. Today Metro is the country’s second-busiest transit system, and its stations have fundamentally changed neighborhoods, bringing thousands of new residents and jobs to places like Clarendon, U Street, and Pentagon City. (Georgetown, where locals once resisted the Metro, now dreams of getting a station.) Of course, these days, Washingtonians are more likely to gripe about Metro than to celebrate it. But even that’s an indication of how important the rail system has become: In 2015, one of Metro’s all-too-frequent meltdowns can ruin your whole day.

1976

“Treasures of Tutankhamun” Opens

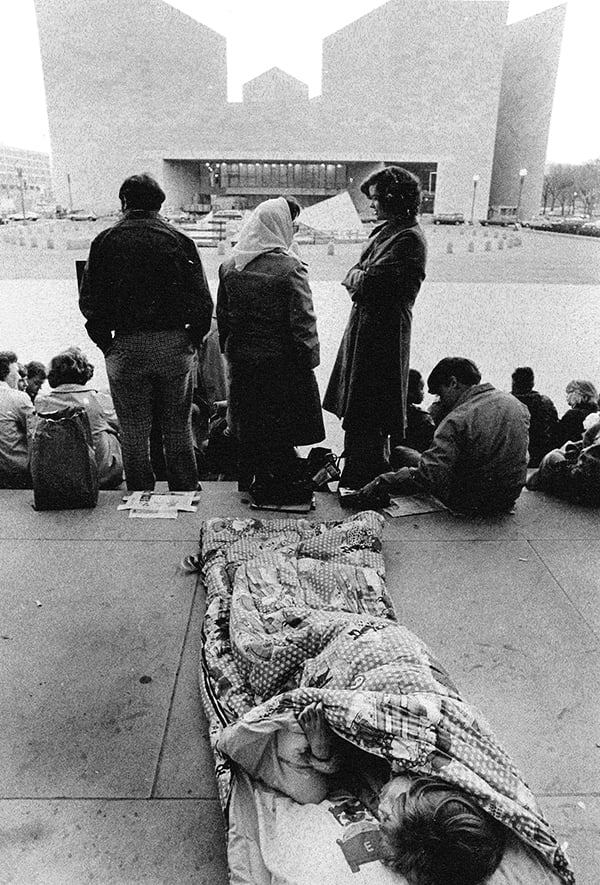

In its early decades, the National Gallery of Art was a conservative place. Then J. Carter Brown took over. He made splashy acquisitions, built an eye-catching modern-art wing, and–to the chagrin of traditionalists–embraced the concept of the “blockbuster” exhibit.

This Egyptian-artifacts show was the first. Some 836,000 visitors queued up. The museum shop sold hundreds of different Tut trinkets. Critics sniffed that “Tut-mania” represented the victory of mass entertainment over fine art. It didn’t matter: Blockbusters like 1981’s Rodin show (more than a million visitors) followed. Along with the National Air and Space Museum–which opened the same year as Tut’s visit–the blockbuster era helped democratize museum-going. The Mall would never be the same.

1976

Elizabeth Taylor Marries John Warner

For Hollywood celebrities, Washington is a famously easy place to wow the locals–just popping in for a hearing on the Hill can merit a gossip-column item. Liz Taylor’s romance with the dashing Virginia senator, by those standards, was some-thing that lasted. In six years as Mrs. Warner, Taylor helped keep local gossips in business.

1977

DC Embraces Gay Rights

When it passed in 1977, DC’s Human Rights Act was one of the country’s first laws protecting gays and lesbians against discrimination. A year later, local elections were in part a referendum on gay rights–and the anti-gay side lost. But though the basic issue was justice, one long-term effect was economic: Drawn to a place that would protect them from arbitrary firings, gays and lesbians became a major local demographic, helping revitalize a city that was hemorrhaging residents.

1978

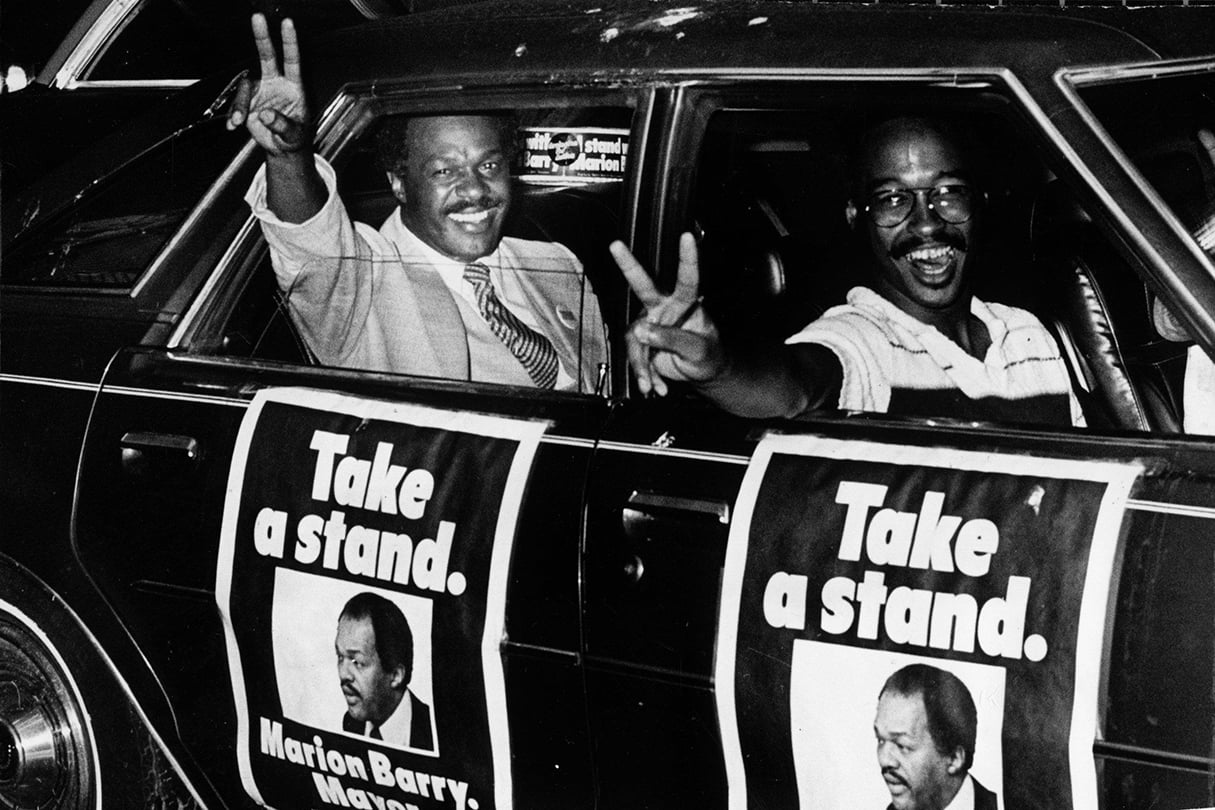

Marion Barry Wins

DC first elected its own mayor in ’74, but the city’s modern political culture was really born four years later, when onetime firebrand Marion Barry won an upset victory. He initially triumphed with support from white liberals but came to embody the hopes of a black majority that had been shut out of government jobs and contracts. Buoyed by a downtown office-building boom, Barry followed the lead of old-time urban bosses and turned the District Building into a hiring machine–without being too fussy about how well the new hires did their jobs. One unintended consequence: Many of those new employees went looking for homes in comparatively well-governed Prince George’s County, which became jokingly known as DC’s Ward 9.

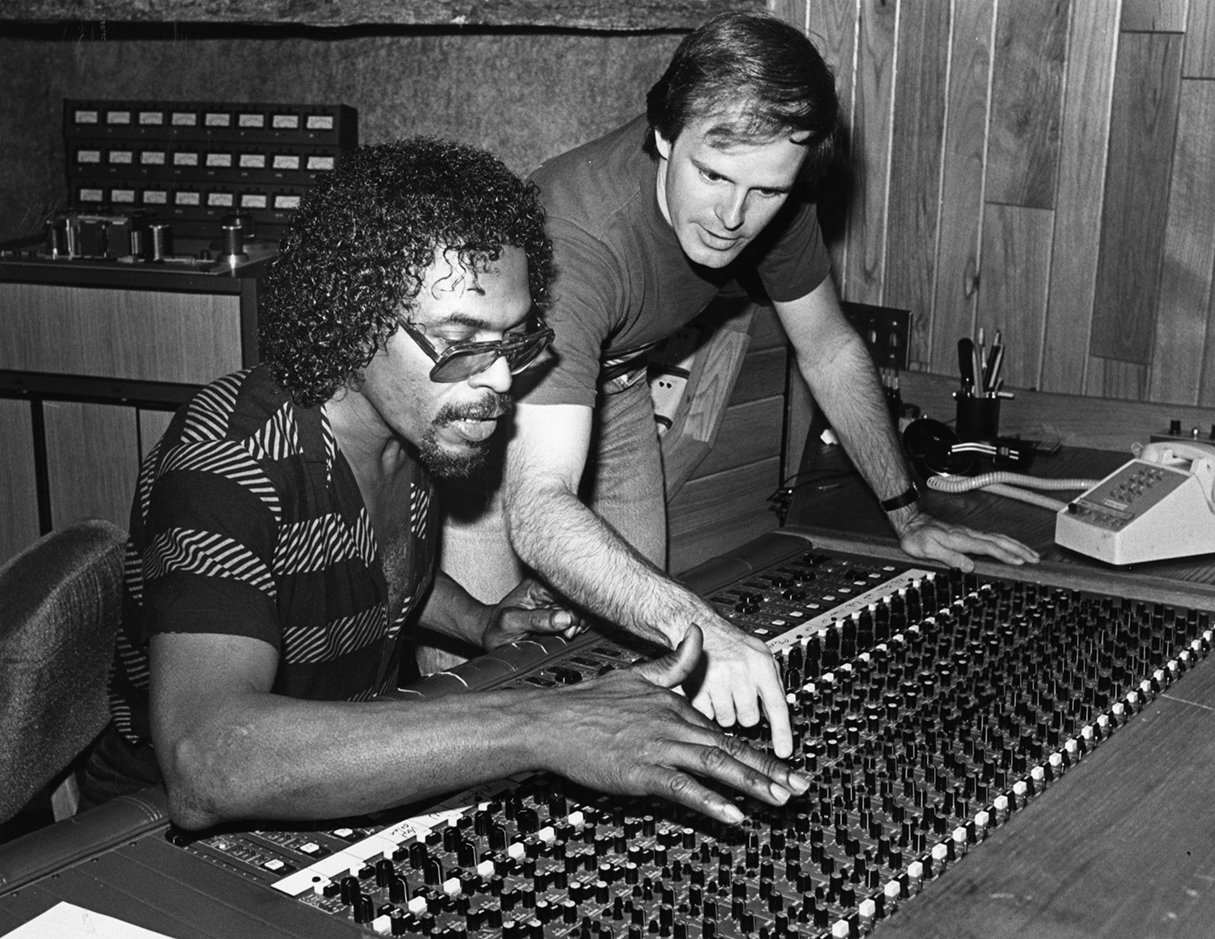

1979

Chuck Brown Records “Bustin’ Loose”

Go-go, DC’s homegrown musical form, emerged slowly from the primordial soup of 1970s funk. If a single song deserves credit for making the percussive subgenre the sound of black Washington in the Barry era, it’s “Bustin’ Loose,” the 1979 number-one R&B hit by Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers.

Go-go would eventually get bigger, groove smoother, and crank harder, but “Bustin’ Loose,” which Brown and his band workshopped as a party anthem for two years before committing it to tape, mapped out the sound’s DNA–its calls and responses, its elemental simplicity, its unstoppable, syncopated beat. “It was the only time in my career that I felt like it’s going to be a hit,” Brown said of the song. “Bustin’ Loose” did more than that. It gave a city its unshakable rhythm.

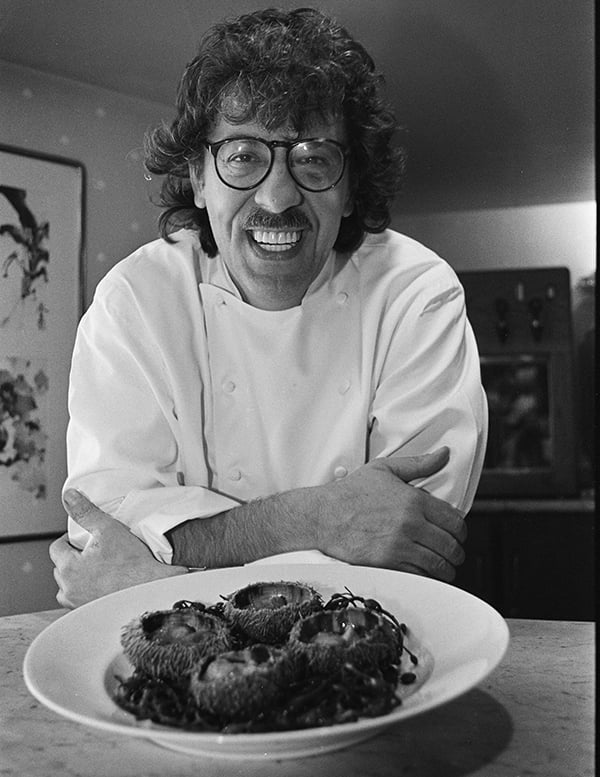

1979

Jean-Louis Palladin Moves to Washington

Once upon a time, the only name Washington diners typically associated with restaurants was that of the maître d’. That changed when a floppy-haired French chef with comically thick glasses–and two Michelin stars–arrived to open a dining room at the Watergate, called Jean-Louis. Palladin got attention for refusing to settle for standard-issue American ingredients (he convinced his seafood purveyor in Maine to suit up in scuba gear and start diving for scallops) and for a daringly unstuffy personality (he once posed starkers in a blender ad). Palladin’s innovations such as consommé with Belon oysters racked up the critical accolades–and Washington got its very first celebrity chef. (Keep an eye out for his profile on washingtonian.com in the upcoming weeks.)

1980

Dischord Records Is Founded

It’s not often we can make legitimate claim to being the center of an artistic movement. But during the 1980s and ’90s, it was fair to call Washington the capital of hardcore punk.

One reason: the culture surrounding Dischord Records, started by Wilson High graduates Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson of the band Minor Threat. The Dischord aesthetic–political, self-reliant, skeptical of drugs and other rock-star indulgences–made DC’s scene stand out, and also helped it last.

1981

Ronald Reagan Takes Office

At the black-tie balls, the guests were draped in jewelry. Private jets crowded National and Dulles airports. The new President himself showed up in a morning coat–the sort of frill that his predecessor, Jimmy Carter, had disdained. It was a new era, all right.

Of course, its long-term local impact wasn’t what critics feared. When Reagan left town eight years later, the federal pay-roll that he had hoped to axe was still pretty robust. In fact, the combination of a defense buildup and a tendency to outsource government work helped Northern Virginia boom.

One particular stylistic innovation from Reagan’s first day in office would outlast the 40th President and transform a Washington ritual: Saying that he wanted to look out at his beloved California, Ronald Reagan moved his swearing-in from the Capitol’s east front to its west front. From then on, instead of facing a parking lot, newly mint-ed Presidents would look out on a gorgeous urban vista.

1981

John Hinckley Shoots the President

The fact that March 30, 1981, doesn’t live alongside November 22, 1963, in infamy is a testament to John Hinckley’s bad aim, Ronald Reagan’s robust physical fitness–and, America later learned, the George Washington University Hospital medical team that saved a President who was much closer to death than authorities let on. But although the shooting neither changed history nor won over actress Jo-die Foster, it did lead to a further strengthening of Washington’s VIP-security culture. These days, Hinckley gets passes to leave St. Elizabeths hospital, but the Secret Service has more power than ever over how a President moves around.

1982

Maya Lin Designs the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

This quiet, magnificent tribute to the 58,000 Americans who died in Vietnam upended the rules of memorial-building. You could now pay honorable tribute to fallen warriors in a setting free of the equestrian statues and laureled colonnades that dominated the District. Of course, the vast, bombastic World War II Memorial, which opened 22 years later, proved that old-school commemorative architecture remained very much alive.

1983

John Riggins Breaks a Tackle

The Redskins were trailing the Dolphins in the fourth quarter of Super Bowl XVII when the running back and honorary Hog broke free, scampering 43 yards to a touchdown. The Skins never trailed again. And the romance between Washington and its team rose to an even higher level.

1984

Georgetown Wins the National Championship

On the court, the Hoyas of the early 1980s were a basketball force–the team that was one bad pass away from a title in 1982, the group that lost an upset in 1985, and especially the squad that won it all in 1984.

Off the court, the impact may have been bigger still. Black superstars had long dominated college hoops, but they’d usually been led by white coaches. This time, they played for John Thompson, the mercurial, brilliant local who just a few years earlier had been subjected to racist taunts from Georgetown’s own fans. The spectacle of a tough, unapologetic team winning it all bonded the Hoyas to the region as nothing before.

1984

Politics and Prose Opens

It seems inevitable, in hindsight, that a bookstore known for serious nonfiction would become a top regional destination: Washington, after all, has an ample supply of people whose idea of a night on the town involves a reading from a new political-history book. But to chalk it up to the area’s nerds is to undersell the accomplishment that is Politics and Prose, which began as a tiny bookshop, survived the age of Barnes & Noble and the rise of Amazon, and built a community so devoted that customers helped lug books when P&P moved across Connecticut Avenue to its expanded current home. When owners Carla Cohen and Barbara Meade decided to sell in 2010, the news wasn’t treated as a simple business transaction involving a small store. The new owners would be custodians of a civic treasure.

1986

Len Bias Overdoses

The University of Maryland basketball star’s shocking death–two days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics–was a tragedy for his family. And as details emerged about the school’s out-of-control sports culture, it became an outrage to Maryland fans, too. But there was also a long-term impact on our culture: Bias’s OD dominated headlines just as crack arrived on DC’s streets. Cocaine, which until then had appeared to be mainly a yuppie indulgence, was suddenly not okay. The drug war was on.

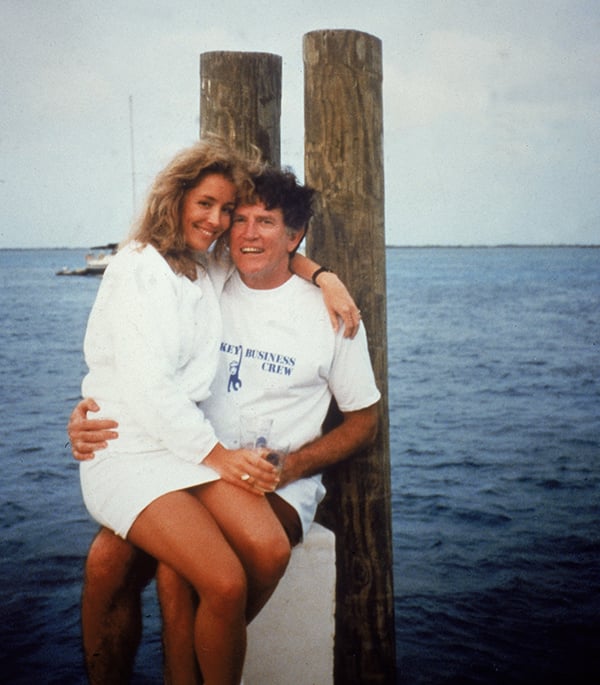

1987

Gary Hart Gets Caught With Donna Rice

When the Miami Herald staked out Hart’s Capitol Hill rowhouse and caught the married Colorado senator with another woman, it meant the end of a presidential campaign. For Washington, it also represented a change in the rules of the game. That same year, a local reporter got hold of Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork’s rental record from a local video store. For people in public life, it was the end of any meaningful distinction between professional and personal life.

1987

Studio Theatre Moves to 14th and P

When founder and former artistic director Joy Zinoman moved Studio Theatre into an old automotive space–it had previously occupied a former hot-dog warehouse on nearby Church Street–the neighborhood’s prospects were bleak. Streetwalkers prowled the sidewalks, mansions on Logan Circle lay derelict, and, Zinoman later said, there wasn’t even a 7-Eleven.

Today, Studio’s original building on 14th Street is just part of a sprawling Zino-plex, home to one of America’s most celebrated theaters. And thanks in part to theatergoers, the neighborhood around it blossomed. It not only has a 7-Eleven–it’s got a Whole Foods.

1989

The Corcoran Cancels Its Robert Mapplethorpe Show

When the Corcoran Gallery of Art axed an exhibit that included homoerotic photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, it was a grim day for Washington’s arts world: In a town with federal money sloshing around, would all controversial shows be subject to veto by culture warriors in Congress? The cancellation, though, sparked a vocal backlash–protesters projected slides of Mapplethorpe’s banned pictures against the side of the museum. Supporters of serious, difficult artwork had learned not to simply trust Uncle Sam’s largesse.

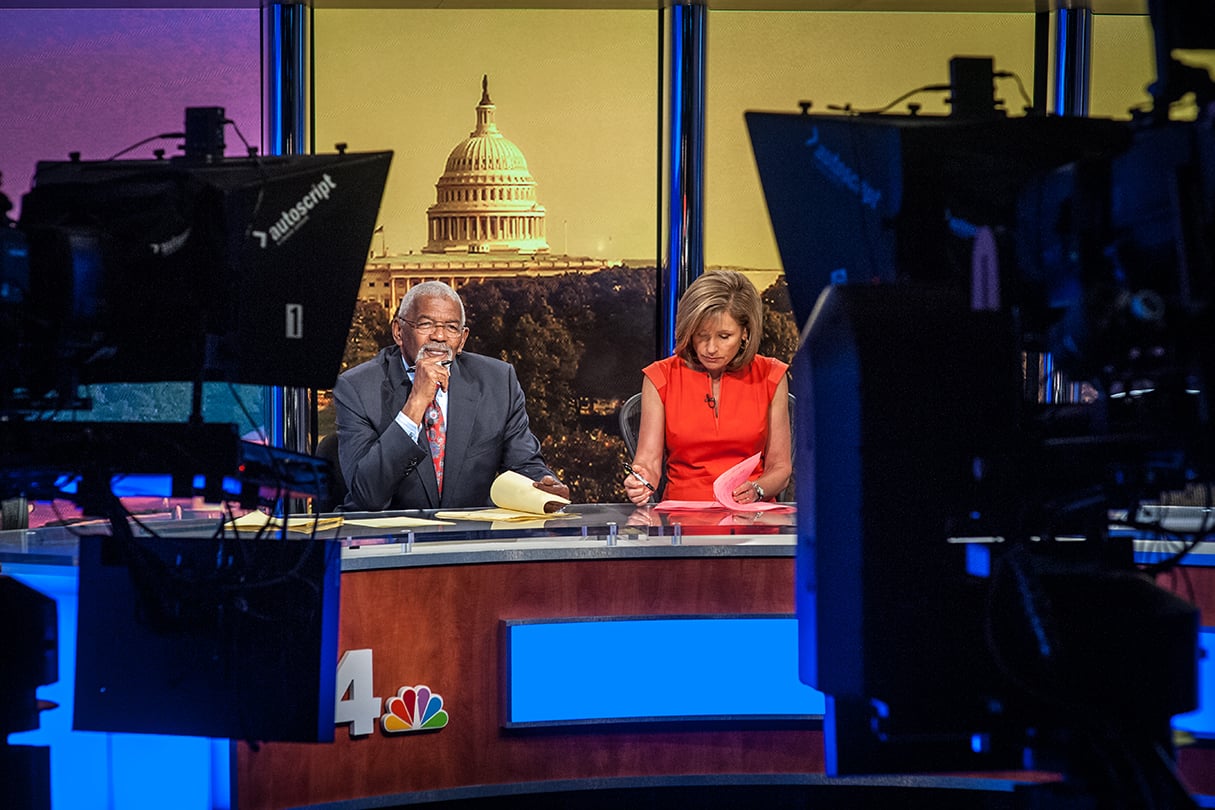

1989

Jim Vance Teams With Doreen Gentzler

Every media market has its beloved him-and-her local news team that everyone thinks has been around forever. In Washington, as it happens, that duo has been in place at Channel 4 long enough for it to seem bizarre that anyone might ever have thought it risky to pair an African-American man with a white woman on the air. Not quite forever, in other words, but an awfully long time.

Vance, 73, recently stopped doing the 11 pm broadcast. But he and Gentzler are still there at 6, as they have been for 26 years.

1990

The Mayor Is Arrested

A hotel room. A crack pipe. “Bitch set me up.” The mayor’s arrest polarized the District along race and class lines while turning Washington into a national joke. What it didn’t do was sever the bond between Marion Barry and voters, who returned him to office in 1994 and elected him to the DC Council four more times.

1991

Anita Hill Speaks Out

When she testified against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, Anita Hill kicked off a national conversation about workplace sexual harassment. Perhaps nowhere was that conversation more needed than in Washington. Lecherous bosses in corporate America could face seven-figure lawsuits. But in federal DC, many bigwigs were exempt from labor laws–and it showed. The Senate that voted on Thomas included the likes of Bob Packwood, who in 1995 would resign his seat amid charges of having serially harassed his own staffers.

By then, the laws had changed. A few years after the Thomas hearings, embarrassed law-makers stopped exempting themselves from antidiscrimination laws.

1994

Wayne Curry Becomes Prince George’s County Executive

It’s hard to believe now, but as late as 1982, a white Republican–Lawrence Hogan, who happens to be the father of Maryland governor Larry Hogan–was chief executive of Prince George’s County. And for 12 years after him, as the county became synonymous with African-American suburban ambition, its power structure remained white. Curry’s election in 1994 (the same year a floundering DC returned Marion Barry to the mayor’s office) marked a major shift in local political power.

1994

Newt Gingrich Leads a Revolution

The Republican sweep of 1994 upended a Capitol where Democrats had done the hiring for 40 years. And for political pros, it represented a seismic cultural change. Instead of getting ahead via the workaday deals that make government function, the new speaker of the House won by waging total war–first against compromisers in his own party, then against Democrats. Today’s bitter, polarized landscape is a major legacy.

Which is why the second, more local legacy is surprising. Working with Democrats, Gingrich’s Republicans forced serious changes on a broke District government. A financial-control board would oversee city hall. A tax credit would beckon new home-buyers. And the mayor would have to hire an independent chief financial officer–a job that eventually went to a nebbishy number-cruncher named Anthony Williams. It all set the stage for a much-celebrated revival and for the less celebrated gentrification that accompanied it. One thing it didn’t do: change how the deeply liberal city votes in national elections.

1997

The MCI Center Opens

As late as the mid-’90s, DC’s historic downtown was a lonely place at night. When Abe Pollin pro-posed an arena for his basketball and hockey teams, supporters promised that bringing 20,000 fans to Gallery Place would change that. Critics grumbled that the venue (now the Verizon Center) would turn the area into an expanse of chain eateries. Both were right. And judging by the crowds in the neighborhood–on game and non-game nights alike–Washington’s pretty happy about it.

1998

Matt Drudge Reports on Monica Lewinsky

At the dawn of the internet-news age, Newsweek got a tip that Bill Clinton had had an affair. The reporting ultimately didn’t get past editors. In the old days, that would have been the end of that. But when Drudge’s theretofore obscure website reported that the magazine had spiked the story, the Lewinsky scandal exploded. Clinton’s impeachment would rivet the country for a year. But the agenda-setting power of Washington’s “responsible” mainstream media would be altered forever.

1999

Dan Snyder Buys the Redskins

Once upon a time, the Redskins were a unifying force, a topic that suburbanites could discuss with city dwellers and that busboys could gab about with Congress members. Two decades of futility have changed that. Now when strangers bond over the Skins, the conversation is often about the owner’s latest display of incompetence, unpleasantness, or vanity.

Would the team still have a lousy record if Jack Kent Cooke’s family had maintained ownership? Maybe. But would they still have a stronger grip on our hearts if the boss weren’t Washington’s favorite bad guy? Almost certainly.

2000

AOL Buys Time Warner

As a government town, Washington has always wanted people to know that its businesses are capable of more than just federal contracting. Boosters took note when the Palm, that most famous power-lunch spot, opened an outpost in tech-heavy Tysons in 1999. Early the next year, when homegrown AOL–then known for the ubiquitous starter CDs that appeared in mailboxes–took over the nation’s most famous media firm, Northern Virginia’s digital economy was officially a big deal.

Of course, the purchase proved an epic disaster. But it was the New York sharpies, not the Virginia newcomers, who took a bath. Today Steve Case remains a local tech godfather and Ted Leonsis managed to buy the Wizards and the Capitals.

2001

United 93 Crashes

For all the genuine trauma, 9/11 did not leave a local legacy on a scale anywhere near New York’s. It was quite possible in Washington not to know anyone whose life was altered when terrorists hit the Pentagon with American Airlines Flight 77. And while Manhattan’s attack left the skyline permanently altered and sent its job market reeling, the tragedy here was, paradoxically, good for the economy. The ensuing war on terror pumped money into security contracting, buoying the region as the rest of the country struggled.

Things might have been very different had passengers not rushed the cockpit of United’s Flight 93, which went down near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. To this day, there’s uncertainty about the hijacked plane’s intended destination–but it’s a good bet that a successful attack would have changed the area in far more dramatic ways. Could you imagine a Washington without the White House? The Capitol? Thanks to Flight 93’s passengers, you don’t have to.

2002

The Beltway Sniper Attacks

A year after 9/11, most Americans were petrified of foreign terrorists. Washingtonians spent much of October 2002 locked down as a result of domestic ones. Not that people knew it at the time. The uncertain source of the gunshots that targeted ordinary citizens as they did things like pump gas or wait for buses was part of what made the sniper period so terrifying. In an age of spectacular terrorism against monumental targets, the rampage reminded us how fragile normal lives can be, too.

2002

José Andrés Opens Zaytinya

The hyper-energetic Spanish chef had already made a name for himself at the helm of Jaleo, the Penn Quarter tapas house that served Washington some of its first tastes of croquetas and tomato bread with Manchego. But it was Andrés’s second restaurant that sparked a revolution. With its miniature distillations of Lebanese, Turkish, and Greek flavors, Zaytinya proved that if you (stylishly) shrink it, they will come. In a town where big, thick expense-account steaks once ruled the fine-dining landscape, small plates now dominate the table.

2005

Riggs Bank Is Sold

The scandal that doomed Riggs National Bank involved shady dealings with foreign dictatorships. But the effect on Washington’s commercial landscape was profound. Riggs was one of the last great local chains. When it went the way of Garfinckel’s, Woodward & Lothrop, and Peoples Drug, the retail scene became a little less distinctive.

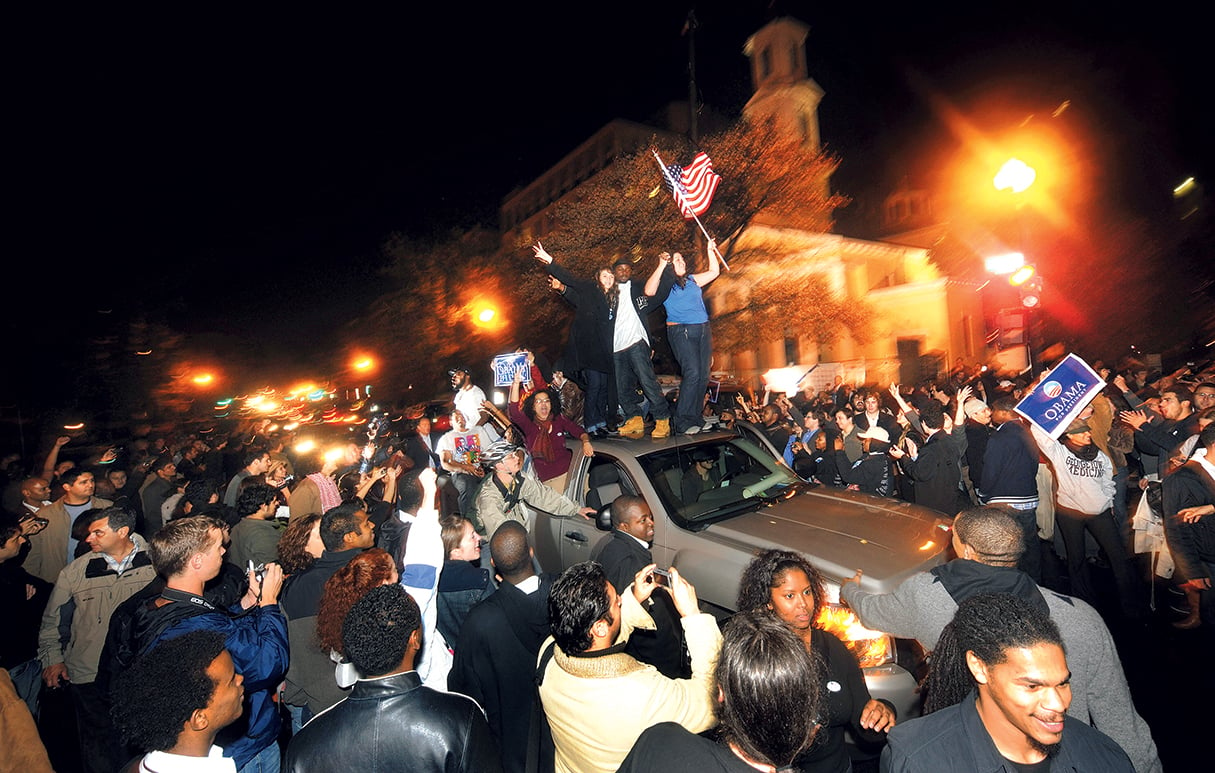

2008

The Obama Era Arrives

Folks wondering why Washington seems overrun by millennials might be tempted to credit Barack Obama, who rode the enthusiasm of young voters to a historic victory. It would be more accurate to assign some of the responsibility to a seismic event that happened a couple of months earlier: the 2008 financial panic. With the national economy in a deep freeze–while the new administration’s spending measure helped our region stay relatively buoyant–greater Washington was, more than ever, the place to be.

2012

Nats Lose in Playoffs

After seven hapless seasons, the Washington Nationals became winners in 2012. They finished the regular season with the best record in baseball and were one out from beating St. Louis in the playoffs.

Then disaster struck. The bullpen surrendered four runs in the top of the ninth, the Nats went home, and fans felt as if they had been kicked in the gut. It was a grim winter. But the long-term impact wasn’t so grim. Baseball lovers know that nothing bonds fans to a team like shared tragedy. After 2012, the Nats were no longer ineffectual newcomers. They were ours.

2013

Jeff Bezos Buys the Post

Just a couple of years ago, picking up the Washington Post was like encountering an old friend who had aged dramatically. The personality and the general contours were the same; they just came wrapped in a body too feeble to do its old tricks.

People talked about chairman Donald Graham with a kind of pity: Even those who believed management had ideas for fixing the Post knew the company was too poor to act on them. With one stunning summer announcement, though, the narrative changed. Graham became the man who took a bullet for the Post, selling his family’s paper to a man with pockets deep enough to navigate the future. Today we’re not sure what Bezos’s Washington Post will become, but it’s clear it’ll have a better shot.

2015

White Flint Is Reinvented

The upscale shopping mall on Rockville Pike was always a trendsetter. When it opened in 1977, Bloomingdale’s was an anchor tenant, prefiguring a time when Washingtonians would want more than local stalwarts like Woodward & Lothrop, Hecht’s, or Garfinckel’s. The mall’s death is also a sign of the times. White Flint is to be replaced by a pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use town center–befitting a suburban county that is much bigger, denser, and more cosmopolitan than anyone back in 1977 could have imagined.

This article appears in our October 2015 issue of Washingtonian.