Downtown Silver Spring has had a nice facelift. But amid all the improving, one landmark is aging gracefully. Crisfield restaurant keeps serving traditional Maryland seafood in an unapologetically simple way. Since 1945, it has sat virtually unchanged on Georgia Avenue near the District line: same sign, same menu.

Crisfield’s popularity stems from more than its fresh seafood. The restaurant is also an ethnic melting pot. Spend an hour at the horseshoe bar and you’ll see what looks like everybody stopping by for a bite. “All people feel at home when they come here,” says co-owner Bruce Mancuso.

When it comes to old-fashioned seafood houses, Crisfield doesn’t have a lot of competition—not anymore. Over the years, plenty of restaurants offered similar fare. In Silver Spring, Wheaton, and Bethesda, there were Fred and Harry’s, the Anchor Inn, and Bish Thompson’s. Today only Crisfield remains. Co-owner Bruce Mancuso doesn’t miss those other places, but he wasn’t thrilled to see them fall by the wayside: “I keep thinking there was writing on the wall for Crisfield.”

Sass from the waitresses? It’s practically on the menu. If oysters are on the specials board, they’re in season. Inquiries about their freshness will often be answered with a look rather than words.

“How’s the rockfish tonight?” asks a newbie at the table next to mine.

“He’s fresh and dead,” says the waitress. “How are you?”

A few of the staff have worked here longer than many customers have been alive. But all of the old-time bartenders are now gone. There was the famous trio who basically ran the joint from the 1950s right up until a few years ago: George Nash, Huck Winn, and Ned Toms.

Nash, down to earth and friendly, died five years ago. Winn, who seemed to shuck oysters in his sleep, died seven years ago. Toms, the last to retire, always found a way to squeeze you into the bar no matter how thick the crowd. He finally hung up his white apron five years ago and now lives in North Carolina with his wife. But for as long as these three have been gone, regulars still come in and ask about them.

Bruce Mancuso recalls a time when those three men were none too happy about having to teach him, then a 17-year-old rookie, the tricks of the trade. “I learned how to shuck an oyster by watching them from a safe distance,” he remembers with a laugh.

Crisfield has been in the Landis family since 1945. Today it’s owned by the third generation. The seven owner/cousins are grandchildren of Lillian Landis, Crisfield’s original owner. An avid traveler, Landis was in the antiques business before she tried her hand at a restaurant. As World War II was ending, she bought the Crisfield name from a local restaurateur. Originally, the place was nothing more than the bar. The dining room was added after the family absorbed the lease of a doughnut shop next door.

Signs of Landis’s past still adorn Crisfield. Beer steins from dozens of travel destinations are shown off on shelves on the walls. In the long dining room is a glass case of antique oyster plates. Among the paintings of old boats are aging photographs of friends, employees, and celebrities. There’s a small “Margaritaville” shrine on the side of the bar where autographed photos prove singer Jimmy Buffett’s love of the place. Everyone from go-go icon Chuck Brown to political satirist Mark Russell has eaten here.

Over the years, suitors have approached the Landis family looking to buy the place. Some offers have been tempting, but none ever made the family jump.

In the late 1980s, Crisfield expanded to a second location. At the busy intersection of Georgia Avenue and Colesville Road, it was newer, nicer, more expensive—and a failure. What it lacked was the intangible hominess, the sense of being “a joint.”

“It was a case of right place, wrong time,” says Mancuso. “Silver Spring wasn’t built up when we decided to put a restaurant there. If we were there now, it would be a home run.” Today the failed Crisfield at Lee Plaza is home to Ray’s the Classics, a thriving second location of Ray’s the Steaks in Arlington. Diners at the new Ray’s look out and see the striking AFI Silver Theatre. When Crisfield was there, the view was far less enchanting.

Crisfield’s long-term relationships reach from behind the bar to across the Chesapeake Bay. The restaurant has used many of the same seafood suppliers for decades. And whenever possible, Crisfield finds seafood from local waters.

“Our blue crab comes from as close to home as we can get it,” says Mancuso. “Sometimes that means Maryland; sometimes that means all the way down to Louisiana. Oysters and clams are almost always from the Delaware Bay, wild, not farmed.”

One supplier, Denny Neagle—father of the Major League Baseball All-Star of the same name—works for US Foods. “We’ve been dealing with him since before they were called US Foods,” says Mancuso. “That’s how long we go back.”

Why has Crisfield outlived many of its customers, much less its competitors? It’s the food—so long as you love seafood and aren’t out to find the latest in modern cuisine. Bouillabaisse at Crisfield? Hardly. But the oyster stew is fresh and simple, made with the same recipe for the last 60 years.

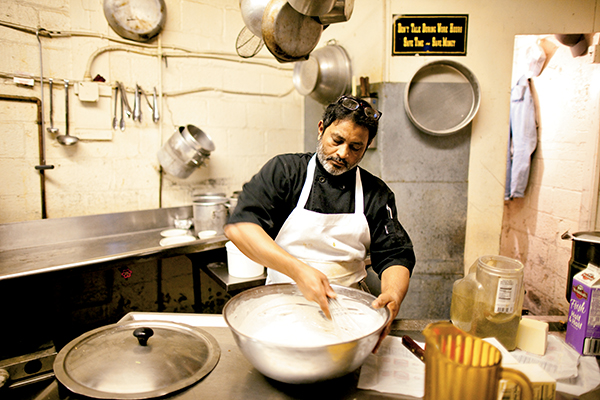

Baked stuffed shrimp is the most popular item. At any time, day or night, it seems half the customers are ordering it. The dish is nothing more than crabmeat tucked inside a split jumbo shrimp, rolled in bread crumbs, and baked until golden brown.

A no-frills raw bar consists of shrimp, clams, and oysters—all piled on a mountain of crushed ice in the aluminum sink under the bar. Haven’t got the nerve to ask for a mignonette sauce with your oysters? Smart move. It’s a coin toss who’d laugh harder—the regulars or the bartenders. Take the raw-bar fare just as it’s offered: fresh, ice cold, with a plastic cup of cocktail sauce and a bottle of Tabasco.

Many folks swear by Crisfield’s cold seafood platter. At $30, you get heaping mounds of chilled crabmeat, peeled shrimp, and lobster. Fans say the trick is to eat half, take the rest home, and sauté the leftovers in butter the following evening.

The dinner rush in the dining room has a pace and atmosphere all to itself. Unlike the front bar, this room is mostly filled with families. It’s where generations sit together and eat the same meal they’ve had dozens of times before. One of the best seats is a booth tucked against the wall in the back, opposite a small window that acts as a pass-through to the kitchen, kitty-corner from where the waitresses congregate. The waitresses provide dinner theater, and you can learn a lot about the restaurant just by keeping your eye on the kitchen window.

The food at Crisfield is king. But beyond that, it’s a living memorial to good times gone by. The place isn’t Cheers—truth be told, nobody knows your name. But if you listen, you might hear a group just like your family having a laugh in the back table by the window.