When I was looking for a TV news job in Washington 17 years ago, my choices were limited. America’s Most Wanted was one of the few national prime-time shows produced here. I knew the work would be interesting; I didn’t know how life-changing it would be.

My first week, a five-year-old girl went missing. Her babysitter, a man in his early twenties, had become obsessed with her and—when her mother tried to keep him away—kidnapped the child.

Before, I couldn’t have imagined what a family went through when a child was missing. Now I was their greatest hope.

Week after week, I pushed their story onto the air. I listened to the mother cry on the phone every day and fretted as days went by and local media began losing interest. I walked down the street thinking of that little girl, wondering if we’d find her.

And then a sighting. The babysitter was seen riding a bicycle in Florida with the child on the handlebars. I had my staff call every TV station in that part of Florida, begging them to run the pictures, to help us find this girl. And we did.

As we arranged to bring the child home, as her mother sobbed with joy on the phone, I became someone who believed—in order, in justice, in the ability to set right what’s wrong.

Over the years, as AMW helped capture hundreds more fugitives—murderers, rapists, pedophiles—people would ask how I was able to deal with such violence and misery every day. I told them it was all about focusing on the people who came to us for help, about seeing the difference we were making in their lives.

I never had a moment’s hesitation—the pain and suffering didn’t faze me.

Until Max was born.

It’s different being an older father—I was pushing 50 when we had Max—and not just because your house is littered with both reading glasses and pacifiers.

When you know there are fewer days ahead of you than behind, the sense of invulnerability that took you through your wild days is gone. Suddenly, the pain and violence I dealt with every day began to take their toll. My colleagues and I were watching a reenactment we’d done of a drive-by shooting in New York. A seven-year-old boy lay dying in his father’s arms. I couldn’t hold back the tears.

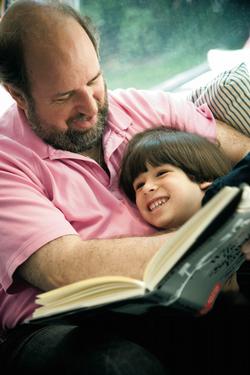

I walked out of the editing room, down the stairs, and into the parking garage, then drove home. Max was on the rug in his playroom, his head on the ground, watching the wheels of a car he rolled back and forth in front of his nose. He looked at me and smiled.

Sometimes, in the following months, I’d feel guilty for quitting my job. But then a little boy in footie pajamas would pad up, hand me a book, and pad away, returning with my reading glasses and a pacifier. And so we’d begin.