On a sunny Friday this spring, a thick haze lingered in the lobby of the Hyatt Dulles in Herndon. It was sweet, like apples and chocolate, and was coming from people huddled around tables near an indoor koi pond, sucking on metal contraptions with skinny mouthpieces that made them look like miniature oboes.

More people sat at the bar, challenging one another to see who could blow the biggest clouds. When I asked the bartender how he liked serving this crowd, he shrugged and said it was okay. Not that long ago, he noted, “you could smoke in here—it was horrible.”

The Virginia Indoor Clean Air Act bans smoking in elevators, public schools, polling places, and restaurants. But the law doesn’t extend to electronic cigarettes or personal vaporizers, which is what people at the Hyatt Dulles were puffing. The battery-powered devices work by heating a liquid nicotine solution and turning it into an inhalable mist. (They are, in effect, wee versions of the fog machine Lady Gaga uses to becloud herself onstage.) The vapor the devices emit looks like cigarette smoke, but they’re noncombustible: no tobacco, smoke, or ash. To use such a device is to “vape.” A person who vapes is a vaper.

About 2,000 vapers were at the Hyatt Dulles for Vapefest, a semiannual gathering for e-cigarette vendors and enthusiasts. First held in 2010, the convention is now billed as the “longest-running vape event in the nation.” It has spawned at least 15 copycats, including VapeBash, Vapestock, Vape-a-Palooza, Vapetoberfest, and, yes, Vapor Gras.

At Vapefest, vapers roamed the Hyatt hallways and rode the elevators dragging on their devices full of flavored e-juice, leaving trails redolent of cinnamon and crème brûlée. Meanwhile, in my room, a placard on the bedspread warned that I’d be hit with a $250 cleaning fee if I stank the place up with cigarettes.

• • •

Throughout Washington and across the country, close encounters with vapers are becoming more common, and it doesn’t take an extreme environment like Vapefest to guarantee a sighting. But you might not know a vaper when you see one. That’s because e-cigs are typically designed to mimic the look of traditional cigarettes—hardcore vapers call them “cig-alikes,” disparagingly—and they glow at the tip when dragged on. Likewise, some personal vaporizers resemble paraphernalia available in a head shop, except they’re sold in vape shops.

Six or seven years ago, there was no such thing as a vape shop. Today there are about 5,000 nationwide, and new stores are opening all the time. The District’s first, called DC Vape Joint, opened in Adams Morgan in March. Many thousands more convenience stores and kiosks, such as those at Union Station and Tysons Corner Center, sell cig-alikes.

There’s also Vape News Magazine, a glossy bimonthly out of St. Louis with 25,000 readers; podcasts (Click, Bang!; The TVA Show); online communities (Vaping Forum, Planet of the Vapes); YouTube channels (Vaped Crusader, Vaping Monkey); and the National Vapers Club, organizer of Vapefest.

For such a young market—e-cigs didn’t appear until around 2006—vaping is already doing big business. Last year, e-cig sales topped $2 billion, according to industry analyst Bonnie Herzog of Wells Fargo Securities. By 2017, Herzog expects sales to surpass $10 billion. At this rate, and barring any red tape that could stifle innovation, she adds, the market could outpace that of traditional cigarettes by 2024—a prospect that hasn’t gone overlooked by Big Tobacco.

The makers of Camels, Marlboros, and Newports have all fired up their own e-cig products. R.J. Reynolds introduced Vuse Digital Vapor Cigarettes in July of last year. Altria has MarkTen, and this past April the company acquired a small e-cig manufacturer called Green Smoke. Blu, the country’s top-selling brand, is made by Lorillard.

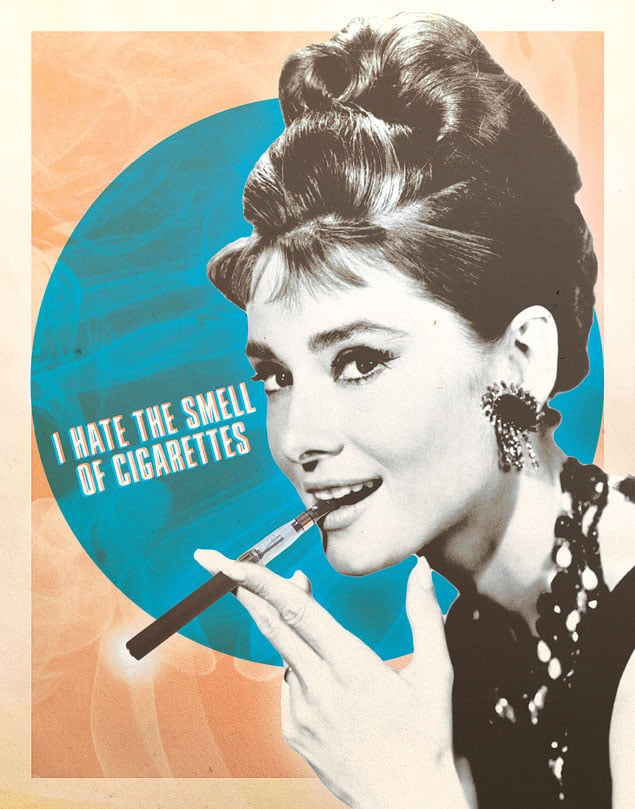

The company got free publicity at the Golden Globe Awards this year when Julia Louis-Dreyfus vaped a Blu as a gag. The audience roared as the Veep star, in black cat-eye sunglasses, an updo, and a strappy red evening gown, puffed importantly on the long black wand, its tip lighting up like an electrified topaz gemstone. (Watch the GIF.)

Lorillard has left the official flacking to former Playboy centerfold Jenny McCarthy, now of The View, who has gushed about Blus in ads for the brand. The message: E-cigs won’t yellow your teeth or make your hair smell, and they can be enjoyed anywhere—no one will give you the stink-eye, she says. The tagline: Take Back Your Freedom.

• • •

The political undertones of Blu’s messaging are probably no accident. In many parts of the country, it’s illegal to smoke indoors or in public places but it’s totally legal to vape, and e-cig makers have a vested interest in seeing that the bans imposed on traditional cigs don’t extend to their replacements—now, especially.

Anti-vaping legislation is on the books in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York, and a growing number of other cities. Locally, DC Council members Yvette Alexander and David Grosso introduced a bill in 2013 that would put e-cigs on par with regular cigarettes, banning their use anywhere smoking is prohibited and barring sales to minors.

Alexander says that several e-cig makers, in an attempt to convince her of their products’ safety, sent samples and, for effect, she puffed on one at a council hearing. The bill didn’t become law, but Alexander plans to reintroduce the legislation.

In Maryland, it’s already illegal to sell e-cigs and vapor products to minors. The same is true in Virginia. Delegate David Albo, sponsor of the bill that passed in that state this past March, says he was moved to act after trying an e-cig for the first time: “My face got tingly. I felt a little bit nauseated. I didn’t want my kid getting ahold of this stuff. I mean, it’s really powerful.” (Virginia, the nation’s third-largest tobacco producer, has otherwise shown itself loath to crack down on vaping.)

Now the US government is poised to apply some of the same muscle to electronic cigarettes that it has to the traditional variety. In 2010, a federal appeals court ruled that the Food and Drug Administration can regulate e-cigs as tobacco products, because the nicotine they contain is derived from tobacco, and in April the agency issued its long-awaited proposed regulations. The FDA wants all manufacturers to provide it with a listing of their devices’ ingredients. Sales to minors would be banned, and all products would have to carry labels warning that nicotine is addictive. If approved, the rules could pave the way for further restrictions: a ban on TV advertising and flavorings that appeal to young people, for instance.

• • •

After years of mostly laissez-faire policy, the prospect of federal limits has interest groups agitating. E-cig opponents who think limits are critical say that the devices make smoking look cool and that they encourage young people to trade up to traditional cigarettes, enticing them with flashy hardware and kid-friendly flavors.

One online purveyor of liquid nicotine products at Vapefest told me that her company offers more than 230 flavors—including strawberry, root beer, and piña colada but also specialties like a six-flavor blend called Demeter’s Harvest. “Those that try this e-juice state it has reminded them of one of their favorite cereals as a child,” the company’s website proclaims.

Lobbies such as the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids want to snuff out the fast-spreading appetite for e-cigs. Results of the National Youth Tobacco Survey released last fall by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that e-cig usage by middle- and high-schoolers more than doubled between 2011 and 2012.

Longtime smokers think the prohibitionists have it backward. At Vapefest, former smoker Joe Barnett, a retired network engineer from Ann Arbor, told me that the devices were his way out of a deadly cigarette habit. “Is this gonna bother you?” he asked politely before taking a draw off his vaporizer as we sat outside the Hyatt’s ballroom.

Barnett was 16 when he had his first cigarette and smoked two packs a day for 35 years. He started vaping in 2010. “Tell you the truth,” he said when asked how he made the switch, “I rented a car and couldn’t smoke in it.” To satisfy his nicotine craving, he bought a V2, a disposable e-cig that retails for about $30 for a five-pack and provides about 400 puffs, the equivalent of two packs of traditional cigarettes.

Barnett became a believer. Last year, he started an advocacy group called the Vaping Militia, and at Vapefest he wore a black T-shirt bearing the group’s name alongside an image of a Minuteman. When I asked about the Revolutionary War reference, he told me not to take it the wrong way: “The idea is to be alert. We warn others.” His group issues online “calls to action,” which make followers aware of local legislation that takes aim at vapers.

But are e-cigs bad for you? Can they cause cancer? Heart disease? Stroke? What happens to people who inhale the secondhand vapor?

The FDA doesn’t have answers to those questions. Long-term studies on vaping don’t yet exist. As part of its ongoing evaluation of e-cigs, the agency is doling out research grants and inviting manufacturers themselves to weigh in.

Njoy, a top-selling brand, is one company that plans to make its case, according to CEO Craig Weiss. Last year, the peer-reviewed American Journal of Health Behavior published results online from the company’s first study. The main finding: Njoy e-cigs could help smokers cut back on traditional cigarettes.

David Abrams might not be the first person you’d expect to agree. He’s executive director of a tobacco-policy think tank at the American Legacy Foundation, a DC anti-smoking nonprofit formed in 1999 as part of the landmark tobacco settlement. “People have tried all sorts of ways to get addicted smokers off of cigarettes, and we’ve had some success,” Abrams says, referring to replacement therapies such as nicotine patches and gum. “But the excitement of the e-cigarette is that it’s a safer way to get nicotine.”

In Abrams’s view, vaping devices are the “disruptive technology” that could help end the chokehold tobacco has on the nation’s 42 million smokers, nearly half a million of whom die each year from smoking-related diseases. “I think we’re missing the biggest public-health opportunity in a century if we get [the regulations] wrong,” he says. “We’ve got to thread this needle just right. We’ve got to both protect kids and non-users and use it as a way to make obsolete the much more lethal cigarette.”

• • •

It’s not clear how long it will take the FDA to make up its mind on the e-cig rules (the public-comment period closes July 9), but the current proposal isn’t likely to extinguish the market anytime soon. The question is: Which companies will be able to hack the bureaucracy that will eventually be upon them?

Big Tobacco has the money to challenge regulations that wouldn’t be favorable. Last year, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, Lorillard, R.J. Reynolds, and Altria spent a combined $14 million lobbying Washington on tobacco-related issues, including e-cigarettes.

That’s serious competition for mom-and-pop e-juice manufacturers and independent e-cig companies that have only recently begun to band together in trade groups. Cynthia Cabrera, executive director of the Smoke-Free Alternatives Trade Association (SFATA), says one of her biggest concerns is the FDA’s “substantial equivalence” requirement, which mandates that all new tobacco products introduced after February 15, 2007, must pass muster with the agency.

For e-cigs to be approved, manufacturers would have to submit their product and show that it’s essentially the same as what was on the market before 2007. Cabrera says this is inappropriate for technology that’s been around only since 2006 and that’s evolving so rapidly: “Basically, it would be like taking your iPhone and going back to whatever was around in 2007,” the year Apple released its first smartphone.

The upshot: Smaller, newer, less flush businesses would struggle to comply compared with the large tobacco companies, which have more resources, infrastructure, and experience.

After the FDA released its proposal, I caught up with Cabrera by phone at Reagan National Airport, where she was on her way home to Hallandale Beach, Florida, before heading to Chicago for SFATA’s spring conference, called Technology Not Tobacco. She described the coming regulations as a “de facto ban” on e-cigs. I asked what the worst-case scenario would be if the proposal were to go through as is. “Extinction of the vapor industry as we know it today,” she said. At least as her members know it.

At Vapefest, over quesadillas and Buffalo wings in the Hyatt’s bar, Adrian Harris of Oxon Hill told me how three months earlier he’d given up his carton-a-week cigarette habit. “The smell of cigarettes does kind of bother me now,” he said. Harris showed off his ZNA, a small, sleek, stainless-steel vaporizer that’s been described on a Reddit forum as “a contraption from Star Trek.” A display window at the base of the device kept track of its battery life. “It has a computer in it,” he pointed out.

It was easy to see that vaping hadn’t only given him a new party trick. It had changed him. Said Harris: “I’m that person now who judges people who are still smoking.”

Jaime Joyce (on Twitter @jaime_joyce) is the author of Moonshine: A Cultural History of America’s Infamous Liquor. Assistant editor Rebecca Nelson contributed reporting.

This article appears in the July 2014 issue of Washingtonian.