If you happen to see a silver-coifed woman driving a burgundy Toyota while making strange faces and loudly mouthing words to herself, that’s Diane Rehm. “I warm up my voice in the car,” she says. “It’s a good thing I have heating and air conditioning because I’m screaming like a banshee.”

Rehm has been at the helm of a weekday public-radio talk show since Jimmy Carter was President. You might expect a 77-year-old who is plagued by a voice disorder and whose husband of 54 years suffers from Parkinson’s disease to toy with retirement. Not Rehm. She has zero intention of hanging up her microphone. Repeat—none.

Last fall, WAMU extended a five-year contract with NPR—which distributes The Diane Rehm Show—for an additional three years, taking the host to age 80. “God forbid I fall sick,” she says. “Then NPR gets out.”

According to WAMU programming director Mark McDonald, her age is not an issue: “Diane can carry on doing the show as long as she wishes.” That freedom has to do with Rehm’s popularity and her razor-sharp mind, which can jump from Vladimir Putin to Pussy Riot to public health with minimal effort.

Her show reaches 2½ million listeners a week, putting her at number 13 among the top 15 shows in public radio, says NPR vice president for programming Eric Nuzum. Listeners on 191 stations continually pledge their affection. Rarely does an episode of her show go by that a caller or two doesn’t gush about how civilized Rehm is, how they appreciate that she doesn’t let guests yell or interrupt.

Rehm’s power, both behind and away from the mike, is legendary. She can be biting to staff if she feels they let her down, a trait I witnessed (and others corroborated) at the Wednesday meeting to decide which of the hundreds of books that flood in weekly will get airtime. A staffer had failed to obtain a timely copy of Robert Gates’s Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War. Rehm’s annoyance was detectable in her withering tone. Then again, if Rehm is ill prepared, it’s her reputation on the line. Says a colleague who likes her: “Diane is the sun in her universe.”

One former producer would talk about Rehm only off the record, but the sentiments aren’t unique, nor are requests for anonymity. “Diane could be a tough taskmaster. She demands a lot of herself as well as those who support her and the program,” the former staffer says. “Producers were expected to put the show above all else. If Diane felt a producer had taken their eye off the ball, they’d be taken to task, sometimes very publicly. Working with Diane could be a great experience, but you did not want to get on her bad side. That could lead to unpleasant outcomes, such as having guest selections questioned, scripts sent back for minor issues, and show ideas rejected out of hand.”

• • •

As for a succession plan once Rehm does step down, there is none—at least that WAMU is sharing. All McDonald will say regarding a post-Rehm future is that he is a “big believer in the call-in format.” When pressed, he dances: “What she’s built here is a very successful show. If and when Diane decides to retire, we will work hard for that legacy to continue.”

Her health scare has been the only threat to her radio longevity thus far. In May 1998, after a six-year medical odyssey, Rehm discovered that the increasing quiver in her voice was a neurological disorder called spasmodic dysphonia. The condition requires medical leave for treatment every five to six months, which means periodic trips to Portland, Oregon, to see her otolaryngologist, Dr. Paul Flint, and to get a Botox shot. Then she needs time off.

“At first, my voice gets down to a whisper, when nothing but air comes out,” Rehm says. “Then it’s very high-pitched. As it comes back, it sounds like Minnie Mouse. Slowly it comes back.”

Of the disorder—which Rehm wrote about in a 1999 memoir, Finding My Voice—McDonald says: “It’s amazing how many people learn to understand the challenges she’s had and learn to listen past it to the content. There’s a small minority who don’t like it.”

If Rehm misses a show, she and her staff turn to a list of substitutes on speed dial, including NPR’s Tom Gjelten, USA Today’s Susan Page, the BBC’s Katty Kay, George Washington University’s Steve Roberts and Frank Sesno, and former PBS NewsHour correspondent Terry Smith.

Sources say Rehm’s replacement would most likely be a woman. Page, for one, claims to be happy where she is and in no hurry: “It’s been such a pleasure and a privilege to fill in. If, and only if, Diane decided she wanted to step down, I’d love to be considered.”

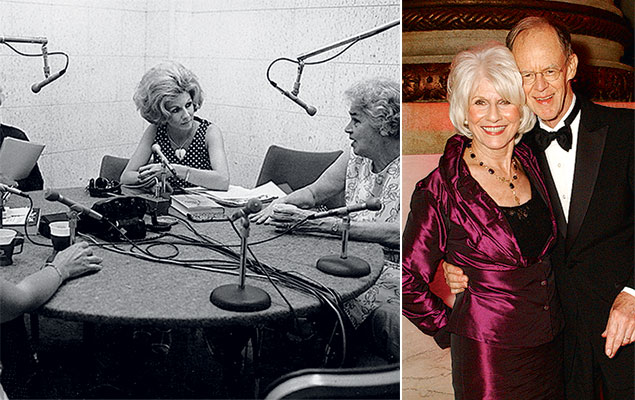

Rehm is clearly neither bored nor interested in the late-life reinvention that former Today host Jane Pauley spoke of on Rehm’s show in a January appearance touting her new book on that subject. The real transformation, Rehm says, occurred when she morphed in the early ’70s from housewife to WAMU volunteer to, in 1979, host of what became The Diane Rehm Show. NPR began distributing the program nationally in 1995.

She told Pauley that she’s “absolutely happy where I am and expect to continue to be.”

To me, Rehm says: “It’s not as though for 35 years I’ve been doing the same thing. I feel as though we are still having a place in the dialogue. ”

• • •

Guests on Rehm’s show see tangible effects from an interview with her. Getting on the second, “book” hour is a goal for many authors and publicists, says Jane Beirn, senior director of publicity for HarperCollins: “We check Amazon the next day, and there’s always an impact. It’s very interesting when an author goes on tour and hears, ‘I heard you on The Diane Rehm Show.’ It gives you an idea of her reach.”

Says Washington literary agent Howard Yoon: “DC is the most literate city in the country. In every publicity meeting I sit through, the goal is to get Fresh Air and then Morning Edition or All Things Considered. A very close second is Diane Rehm.”

She has even indirectly helped careers. CBS chief White House correspondent Major Garrett says that during his seven years at the Washington Times, he was often a guest on Rehm’s show. In 1998, when he applied for a job at U.S. News & World Report, a few editors hesitated, feeling his objectivity might be tainted because he’d worked for the Unification Church-owned Times. Several U.S. News editors said Garrett had proved his professionalism on Rehm’s program. He was hired.

“The most important evidence that I was qualified for the job, other than my work,” Garrett says, “was being on Diane Rehm.”

Elise Labott, a CNN foreign-affairs reporter, has gotten sources from her appearances. She was on Rehm’s Friday “international roundup” after Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak stepped down in 2011. A White House official called Labott afterward to provide updates on the situation.

Labott admits Rehm can be intimidating: “Diane’s interviewing style is very much like her personality—disarming charm with a steely toughness. I love her, but I’m also a wee bit scared of her, and that has made me a better guest and a better journalist. It’s not enough to have read up on your topics—you have to be able to analyze events and defend your arguments.”

• • •

Rehm is out of bed at 5 in the morning at her condo on New Mexico Avenue near American University. She drinks exactly two cups of coffee. Every night, she has two glasses of ice-cold Champagne. (“It feels really good on my throat.”) She’s in bed by 9:30.

One day a week, she follows the Fast Diet, devised by British physician Michael Mosley. She begins that day with two ounces of Gruyère cheese and coffee. Lunch is nonfat yogurt, dinner a small serving of fish or chicken and a vegetable. She drinks lots of water. She has lost 20 pounds since last March and has had 17 jackets altered. Rail-thin (she prefers I use the word “slender”), Rehm says: “I feel terrific. It’s the best diet I’ve done in my life.”

Listeners know about the weight loss because she shares details of her life on the air, at events, and in her books. They know about her dog, Maxie, because she wrote a 2010 book about him. They know that her best friend, Jane Holmes Dixon, an Episcopal bishop, died on Christmas Day 2012 because Rehm shared the news on the air and later rebroadcast a conversation in which the pair talked about their 30-plus-year friendship.

Listeners know about her husband, John—an attorney in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations and later in private practice—who, like so many fathers of his generation, came to regret spending more time at the office than at home. They know that because the Rehms cowrote a frank 2002 book, Toward Commitment, about the ups and downs in their marriage. Listeners know that last year Rehm’s husband, now 83, was moved into assisted living to get constant care for his Parkinson’s. “I never thought I would live apart from John Rehm after all these years,” she says.

When I ask her why she shares so much, I note that I know nothing, for example, about the personal life of Tom Ashbrook, host of another popular public-radio talk show, On Point. She leans in and slowly asks, “Do you care about Tom Ashbrook?”

Rehm’s theory is that to truly connect with others, she needs to talk about her life: “You should see the cards, the letters I get—people worrying about my voice, my husband, wondering about my kids, my grandchildren. I mean, would you ever write that kind of letter to Tom Ashbrook? I don’t think so.

“He has a good following. He started a lot later than I did. He’s just not a real person on the program. He’s just a talk-show host.”

Alicia C. Shepard is a former NPR ombudsman. This article appears in the May 2014 issue of Washingtonian.