An atheist will most likely emerge from Freud’s Last Session at Theater J with her or his skepticism intact, a believer with faith unbowed. And both will have had a quietly enjoyable time of it, for there is a kind of secular spiritual uplift that comes with watching a terrific actor bring a character intensely to life.

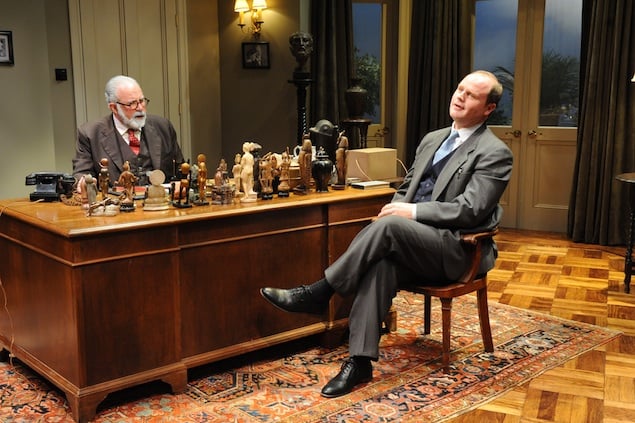

That would be Rick Foucheux, who creates such a fully human portrait of Sigmund Freud in the last year of his life that an audience will feel they’ve paid the man a personal visit via time travel. The pioneer of psychoanalysis hosts the much younger scholar and devout Christian C.S. Lewis (Todd Scofield) in his London study in 1939. (Freud fled Nazi-occupied Vienna the previous year.) The two men jump right into a debate about the existence of God; an afterlife; whether humans are born with a moral conscience; and whether war, loss, pain, and sickness—Freud is terminally ill, and Hitler has just invaded Poland—are punishments from God or proof there is no deity.

The topic may seem too dry for some theatergoers, and the play by Mark St. Germain does at times fall into patness and predictability. But the 80-minute intellectual tennis match will feel short and salutary for those in search of a good sit-down with a couple of brilliant thinkers.

Lewis, who didn’t accept Christianity until he was an adult and had survived fighting in World War I, describes himself as “the most reluctant convert in all of England,” and the God of the Bible as “a bullying busybody.” Yet he believes. He accuses Freud of undue pride and of being “bombastic” in his lifelong effort to debunk religion. He suspects Freud must have a secret yearning for faith. He argues that free will, granted by God, is “the only thing that makes goodness possible” and that humans are born with a moral conscience.

Freud counters that conscience is taught. He sums up religion as “an insidious lie,” chides Lewis that in his adult conversion he succumbed to a hallucination and “abandoned facts for fairy tales.” Freud remains “convinced that Christ was a lunatic,” citing the dozens of patients he treated who thought they were Christ. Darwin is his saint, he tells Lewis, who in turn asks him why science makes no room for religion.

The encounter is imaginary. St. Germain based the piece on a dialectic created by Armand Nicholi’s 2002 book (and a PBS series), The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of Life, which grew out of a course Nicholi taught at Harvard.

There is more than a whiff of the printed page about the play, and St. Germain’s efforts to break things up with phone calls, radio broadcasts, and even an air-raid siren feel too convenient. Yet Foucheux and Scofield, under Serge Seiden’s direction, do fine work making the play live and keeping any artificiality in check.

Scofield’s solid Lewis, all British rectitude and relative youth (in his early 40s compared to Freud in his early 80s), is, alas, not nearly as interesting as Freud in this setting, even though St. Germain tips the emotional scales slightly in Lewis’s favor. “Psychoanalysis doesn’t profess the arrogance of religion, thank God,” says Freud at one point, before catching himself. Seeing Lewis’s delight, Freud concedes that casually thanking God in conversation is a habit he has yet to break. It’s intended as an “aha!” moment.

Throughout the play, it is Foucheux’s cranky, arrogant, ironic secular-Jewish Freud who pulls in the audience—even those who personally reject his rejection of faith. The two men converse in a handsomely wrought study (set design by Deb Booth), complete with enormous desk, Oriental rugs, and, of course, a couch. A curved back wall of tall windows and French doors looks onto a garden. The date is September 3, 1939, two days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland. The men turn on the radio to hear Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announce that war has been declared, and later to hear King George VI rally his people. Both leaders invoke God, prompting Freud to roll his eyes.

Other interruptions are medical. Freud is dying from mouth and jaw cancer. Surgeries have removed most of the roof of his mouth. He wears a prosthesis, he tells Lewis, to keep food and drink from entering his nasal cavity. At one point, Lewis helps Freud, in a sudden bout of pain and bleeding, remove and clean the prosthesis. It is one of the most harrowing theatrical moments about serious illness this reviewer has seen on a stage.

The meeting doesn’t conclude so much as just end. Freud expects his doctor and his daughter, Anna, so it’s time for Lewis to go. The debate is over, and mortality—or is it immortality?—awaits.

Freud’s Last Session is at Theater J through June 29. Running time is about 80 minutes, with no intermission. Tickets ($35 to $65) are available online.