2014 Washingtonians of the Year

Nine local heroes whose good works and generous spirits make Washington a great place.

By Leslie Milk | Photographs by Greg Kahn

Ann H. Bissell

A passion for pachyderms

When Smithsonian secretary Wayne Clough first came to the National Zoo after being named to the post, he stopped a caretaker in the elephant enclosure and asked how she liked her job. “I was covered in straw and sweat, and I told him I loved my job,” Ann Bissell recalls. Then she added: “I’m a volunteer.”

Bissell has spent three days a week with the elephants for more than a decade. As a zookeeper aide, she prepares their meals, gives them baths, and cleans up after the enormous animals. She hides food in toys to create scavenger hunts for her charges. “Bored elephants,” she says, “are unhappy elephants.”

Volunteers save the zoo about $4 million a year, according to Bissell, who also serves on the board to Friends of the National Zoo and is a generous contributor to the zoo.

Growing up in DC, Bissell was a frequent visitor to the zoo. She told her parents she wanted to be a zookeeper, though the sight of lions and tigers in cages sometimes brought her to tears. Convinced by her family that this wasn’t a good career choice, she pursued another profession.

Bissell is owner of Associated Designers, a lighting-design company in the District. However, her heart has always been in elephants.

Now free to enjoy the animals she loves, Bissell hopes people will continue to have the same opportunity. “The younger generation has to be turned to environmental biology,” she says. “It’s going to take everybody’s effort to save species. Working here at the zoo and talking to school groups, I feel I’m making the best contribution I can.”

“The younger generation has to be turned to environmental biology. It’s going to take everybody’s effort to save species.”

Arch Campbell

Shining the spotlight on arts

For 40 years, arch Campbell appeared on local TV, touting the richness of the local cultural community and—what he’s best known for—offering pithy opinions on movies and theater productions. His enthusiasm about the films and plays he loves has encouraged viewers to go out and see something they might have missed.

Campbell found his voice as a seventh-grader in San Antonio delivering announcements over the PA system. He studied radio and television at the University of Texas at Austin, then became a movie reviewer when he was working in a Dallas TV newsroom and no one else volunteered. After he moved to DC’s Channel 4 in 1974, he started out doing a bit of everything but by 1979 was regularly covering arts and entertainment. He often ad-libbed theater reviews, using slides to illustrate the productions. “Casts would gather around a TV to watch,” he recalls.

“Arch has always recognized that theater is fundamental to our community,” says Linda Levy of Theatre Washington, which presents the Helen Hayes Awards. “Without question, he helped develop Washington audiences, who then brought their buying power into neighborhoods.”

He’s equally dedicated to helping people with colon cancer, a disease he battled. Patients get in touch with him through his doctor, Fred Smith, and Campbell helps them see by example that the disease is survivable. “All I have to do is show up and say, ‘I had colon cancer nine years ago—let’s get some lunch,’ ” he says.

Eight years ago, he moved to Channel 7. He recently left, but you can still hear his basso chuckle weekly on WNEW-FM and occasionally on his friend Tony Kornheiser’s ESPN Radio show. He also emcees events for ArtStream, a group offering stage opportunities for people with disabilities and others. “I want to be an advocate for the arts,” he says. “These places are important.”

Gerald R. Sigal

Constructing Children's Futures

Having grown up in a Brooklyn tenement, Gerry Sigal knows what it’s like to be disadvantaged and discounted. As a boy, he delivered groceries to earn money. He put himself through school, went to work for a New York construction company, and eventually settled in Washington, where he started his own successful business, Sigal Construction Corporation.

In 1995, he read in the paper that the bathrooms at many DC schools were unusable, and he was instantly returned to his roots. He contacted colleagues, clients, and friends, and Operation Spiffy John was born. By the time they were done, Sigal and company had rehabbed restrooms in 14 schools.

He also realized that while unemployment in the District was a chronic problem, public schools didn’t offer a vocational program to train kids for jobs in his own field. So he helped found DC Students Construction Trades Foundation and the public/private partnership that created the Academy of Construction & Design at Cardozo Education Campus. “Lots of young girls who didn’t think of this before are in the program,” Sigal says. “We’ve taught them to be carpenters, plumbers, electrical workers. Some have gone on to college.”

This year, he established an annual award for the outstanding Career and Technical Education student at the academy. The first winner, Treymane Chatman, was hired by Sigal’s company on graduating from Cardozo and became a registered apprentice after just 90 days.

Sigal also awards a scholarship to one District student to attend Parsons design school in New York. He’s on the National Building Museum board and helped rally support for constructing the BIG Maze that delighted museum visitors last summer. In addition, Sigal organized a relief fund to help families of 9/11 victims at the Pentagon. Appointed by President Clinton to the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, he’s now co-developer of the new Holocaust archival-research-and-scholarship building to be built in Prince George’s County.

“I’m from the streets of Brooklyn,” Sigal says. “I’m very fortunate. I believe people have to give back.”

Duane Gautier

Bringing new life to Anacostia

"Every neighborhood, whatever the income, deserves good art and culture.”

Walk into Honfleur Gallery, with its white walls, pale wood floors, and colorful art, and you might think you’re in SoHo. But this is Anacostia, and the work is by an east-of-the-river artist yet to be widely known.

Honfleur is part of the Anacostia Arts Center, which founder Duane Gautier sees as a catalyst toward changing the sometimes troubled area and people’s views of it. “Every neighborhood, whatever the income, deserves good art and culture,” he says. Gautier started the center’s parent organization, ARCH Development Corporation, in 1991. The arts center, which opened in 2013, includes a black-box theater, galleries, boutiques, and a cafe.

Gautier was working for Pepco in the ’80s when he began a “green” job-development nonprofit in Anacostia. Funded by Pepco and the DC school system, it offered low-income homeowners weatherization services. Finding no local workers trained to do the work, Gautier started ARCH Training Center in 1986. He bought a house for students to work on, then sold it, thus beginning ARCH’s housing program—a project that provided 900 units, including for homeless vets. By 1994, he had left Pepco but continued to focus on training. While consulting abroad, he helped set up artist cooperatives. Gautier returned home with the idea that art could be an economic engine.

When Honfleur opened in 2007, a critic told him no one would come. But they did—and not just to the gallery: In its first year, the Anacostia Arts Center welcomed 24,000 people. The 2012 arts festival Lumen8Anacostia attracted 3,000-plus visitors to the neighborhood on one Saturday. Gautier hopes his efforts will bring both long-term investment and spending money. It seems to be happening: Kera Carpenter of Petworth’s Domku restaurant opened Nürish Food & Drink in the arts center a year ago, and center spaces have drawn two resident theater companies plus a wellness collective. Andy Shallal is reportedly planning a Busboys and Poets and a culinary training center nearby. Thanks to Duane Gautier, Washingtonians are discovering a new Anacostia.

Tawanda Hanible

Mentoring at-risk kids

Marine Gunnery Sergeant Tawanda “Tee” Hanible is an Iraq War vet, but some of the toughest battles she’s fought were on the streets of Chicago as a teenager. “I didn’t think my family understood me,” she recalls. “I acted out in so many wrong ways.”

Her adoptive mother sent a teenage Tee off to a military school run by the National Guard. After Hanible graduated, she followed her brother into the Marines. Still on active duty, Hanible has been stationed at Quantico since 2011. She’d previously volunteered in every community where she’d served, including as a Big Sister, and planned to look for similar opportunities in Virginia, but of the mentoring programs she contacted, one had a yearlong wait for volunteers and another charged the families it worked with. So Hanible started her own.

Operation Heroes Connect enables servicemembers and vets to mentor at-risk kids, many living in homeless shelters. The youths themselves pick their mentors, and the adults agree to get together with the kids at least once a week. They see them after school, attend their games, become part of their lives. There are 32 children in the program and 38 volunteers.

“I see myself in a lot of these kids,” Hanible says. The girl she mentors, 16-year-old Beja, is a “firecracker.” They bump heads, “but at the end of the day, I’m the first one she calls.”

Operation Heroes Connect has also sent more than 4,000 holiday cards to deployed servicemembers and collected toys for needy children. Last year, Hanible created 30 Days of Giving to distribute donated clothing and food to local homeless communities.

Hanible—who has been recognized for her volunteer efforts by the Marine Corps and the USO—is inspired by her mom, who fostered 30 children in addition to adopting Hanible and her brother. “Without her stepping forward, I think: Where would my brother be?” she says. “Where would I be?”

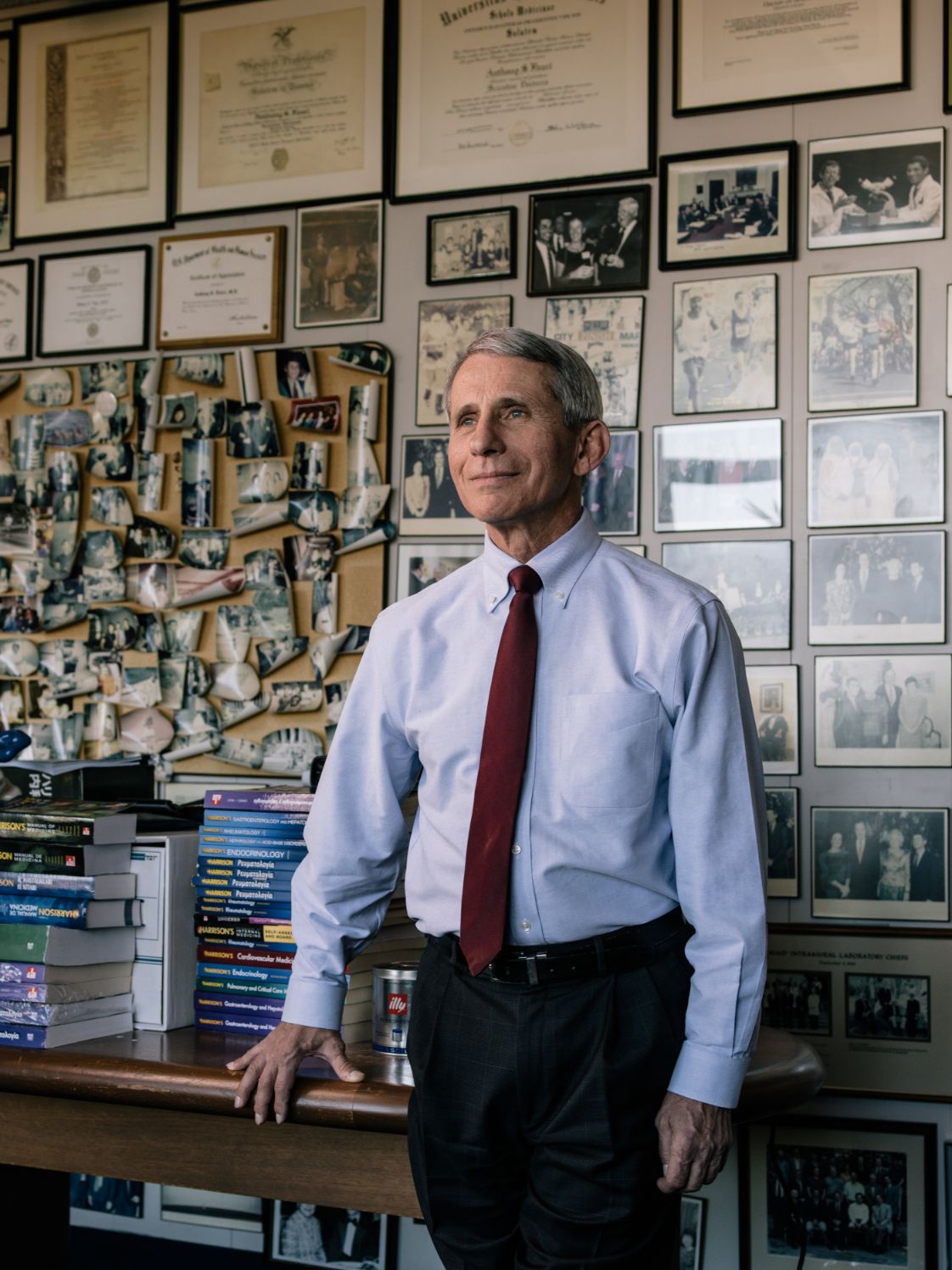

Anthony Fauci

This doctor's prescription: public service

Dr. Anthony Fauci has spent his professional life at NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the last 30 as director. Fauci relishes the challenges: to take care of patients while researching global problems and developing cures for fatal illnesses. His early years had triumphs—he and colleagues discovered therapies for once deadly inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases—but in 1981 his career changed when he began working on the first cases of what was later found to be AIDS. “We were dealing with a killer and didn’t know what it was,” Fauci recalls. “I made the decision to devote myself to finding this disease and a cure.” He has worked on HIV and AIDS ever since—laboring in the lab, funding other researchers, lobbying Congress, making his case in the media. Today, a “cocktail” of drugs can enable HIV/AIDS patients to lead active, normal lives.

President Bush sent Fauci to Africa in 2002 to bring AIDS care and prevention there. The Obama White House has consulted him on Ebola, and he treated a nurse infected with the disease. Winner of the National Medal of Freedom and the Presidential Medal of Science, Fauci could rest on his laurels. But there’s an HIV vaccine to develop, and he hopes to see malaria and universal influenza vaccines. “I love the electric atmosphere of this place,” he says of his work, “the critical mass of dedicated people.”

Carol Pensky

Helping navigate grief and loss

Carol Pensky met William Wendt, founder of what was then the St. Francis Center, in 1983 after her mother died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. A social worker from the center for the terminally ill and bereaved had been a comfort to her mom and mentioned Pensky to Wendt. He reached out to her and, as she puts it, “it was love at first sight.”

An Episcopal priest, Wendt believed in the power of presence, being there for people at the end of life and their loved ones. Pensky has been there ever since as a volunteer leader of the renamed Wendt Center for Loss and Healing. “It’s no exaggeration to say the center is here today in large part because of the efforts of Carol,” says executive director Michelle Palmer.

Pensky has been instrumental in widening the organization’s reach. She encouraged the center, in Northwest DC, to open an office in Anacostia, where residents in high-risk neighborhoods suffer disproportionately from family loss and violence. She and her husband, David, provided seed money for the center’s first program for kids. Staff go where the children are, running therapy groups in more than 20 District schools. Says Pensky: “We have evidence that 85 percent of the kids receiving counseling have shown an absence of depression and anxiety compared to other children who have experienced traumatic losses.” She often joins in the center’s sleep-away camp, where children and volunteers are united by their common experience of losing a loved one.

William Wendt gave Pensky a great gift, she says. He told her of being called to New York by an old friend whose wife had terminal cancer. The wife had asked for Wendt because she knew he would come just to be with her. He did, offering simple comforts like rubbing her feet. The day before Wendt himself died in 2001, Pensky visited him. “I rubbed his feet,” she says.

Rushern Baker III

Making Prince George's proud

Prince George’s county Executive Rushern Baker III is aiming high. Since he took office four years ago, more than $6 billion in development has begun, including an MGM casino, Tanger Outlets at National Harbor, and a planned regional medical center in Largo. Baker meets weekly with the police, sheriff’s, and corrections departments and the state’s attorney to strategize about crime reduction—and cites a crime rate that’s the lowest in almost 30 years. He appointed a new school superintendent and helped restructure the school board. The county is revitalizing blighted neighborhoods—removing abandoned buildings, repaving streets, encouraging citizen involvement. “I want to bring back what I felt when I moved to Prince George’s in the late ’80s,” Baker says. “That this was a place on the rise.”

Baker was a poor student whose father was in the military, and the family moved around before settling in Beverly, Massachusetts. There he met cousins from Springfield, some of whom were all too familiar with the juvenile-justice system. Baker realized the advantages he’d had. A conversation with his dad inspired his political ambitions. When Rushern railed against a do-nothing politician, his father said: “If you think you can do better, you should run for office.” Baker attended Howard University for college and law school. He first ran for office in Prince George’s in 1994 and served in the Maryland House of Delegates till 2003. He lost two races for county executive before winning the post in 2010.

In 2012, he revealed that his wife, Christa, suffers from early-onset dementia. He’s a passionate advocate for those affected by the disease while remaining devoted to the county: “I want my kids to want to stay here. I want everyone to feel proud to be in Prince George’s County.”

Mark Bergel

Fighting poverty one bed at a time

"The people I meet are suffering. I can’t be cautious.”

When people in need come to A Wider Circle, they get something more precious than free home furnishings or clothes suitable for job-hunting. They get respect.

Founder Mark Bergel believes recipients should be treated as valued clients. Donated furniture is arranged as in a retail showroom, and there are personal shoppers and dressing rooms. Everyone is greeted with a smile; no one asks for an ID. The organization also offers workshops in job readiness, from résumé-writing to interviewing skills—Bergel believes it’s impossible to escape poverty without a job—as well as financial planning, nutrition, and stress management. “Poverty is 100 percent stress,” he says.

A Wider Circle furnishes more than 4,000 homes a year from its Silver Spring warehouse, and clients are referred by 300-plus government and nonprofit agencies. More than 15,000 people volunteer each year—people Bergel hopes will become committed to his cause.

After Bergel got his PhD in sociology at AU, two professors encouraged him to teach a course on his passion: combatting poverty. He began A Wider Circle in 2001 following a visit with students to a family who lived in an apartment containing only a chair and a TV. It was life-changing for the teacher, who vowed: “I will not sleep in a bed until everyone in need is able to sleep in a bed. I will sleep on the floor and the couch and let that inspire me to work harder on behalf of those in poverty.” (Long single, he has stuck to the promise.)

Bergel began by asking people he knew to donate furniture. He stashed pieces in friends’ garages and borrowed vans for pickups. His students became his interns. Eventually he acquired an abandoned warehouse—a move some nonprofit leaders might have questioned. Not this one: “The people I meet are suffering. I can’t be cautious.” His goal isn’t to make comfortable people feel guilty but to empower everyone to do something. Says Bergel: “Our nation’s capital has to be a model of what is possible.”

This article appears in the January 2015 issue of Washingtonian.