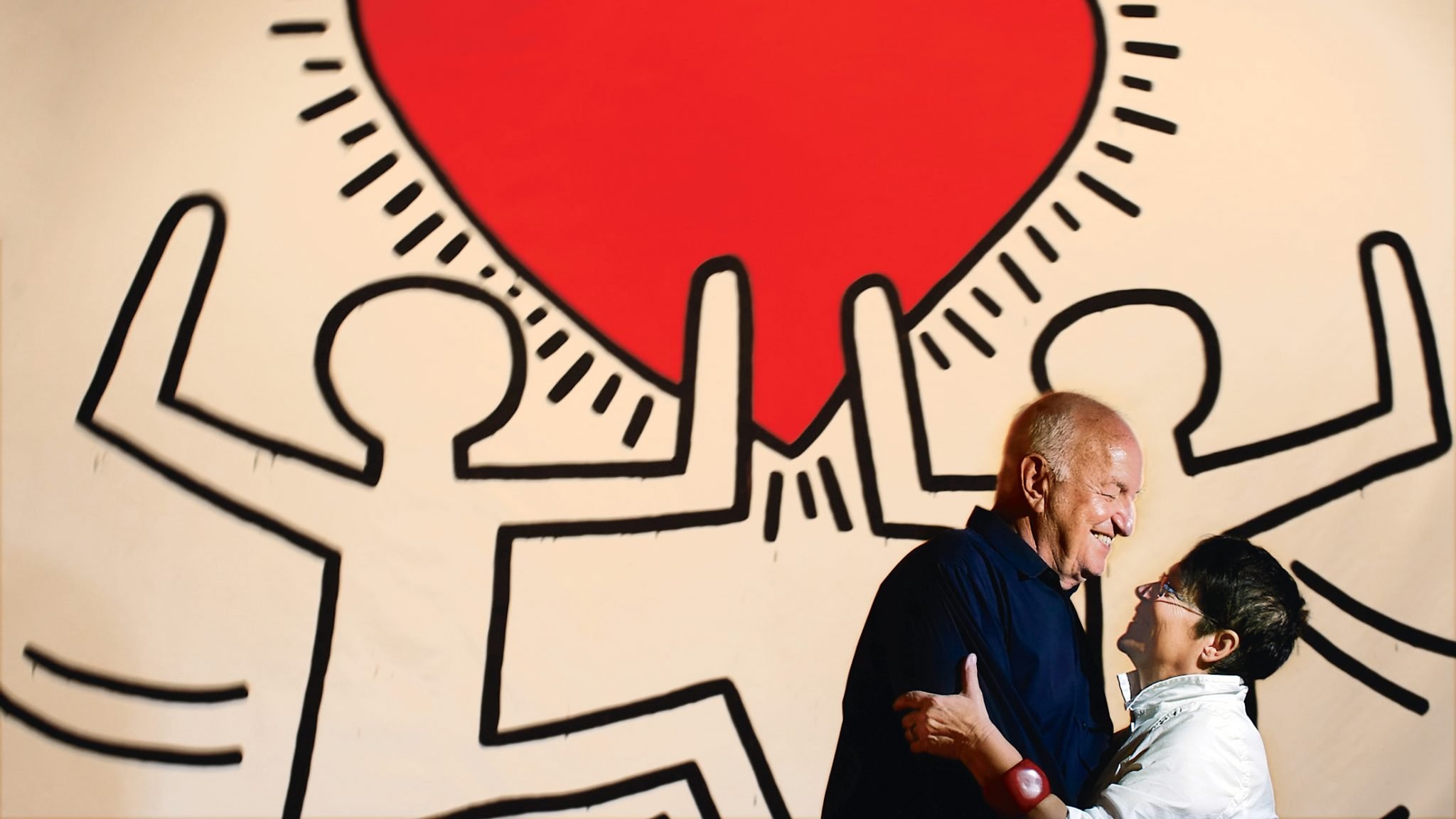

As they’ve built one of the world’s largest private art collections, Mera and Donald Rubell have adopted cities the way they take an interest in artists: getting in deep before anyone else and ultimately creating stars. In the 1990s, the New York transplants helped turn Miami’s South Beach into a destination for fashion and art-world luminaries by restoring the neighborhood’s aging Art Deco oceanfront hotels, just as in the previous decade they had championed New York painters Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, buying their canvases long before those artists became celebrities.

In 2002, it looked as if it was Washington’s turn. That year, the couple took a huge gamble on the Capitol Skyline Hotel, a dilapidated Best Western five blocks from the US Capitol building, in a part of Southwest DC still suffering from a failed 1960s redevelopment effort. The Rubells—drawn by the sweeping curves and futuristic design by Miami architect Morris Lapidus, a friend—bought the building for $7.2 million. New York interior designer Scott Sanders did a renovation; Frank Gehry chairs and other artistic flourishes were installed in the lobby. Today the place is best known for its pool parties.

“Everyone said, ‘You can’t go near this hotel. It’s the worst neighborhood and you’re from out of town and you’re making a big mistake,’ ” says Mera Rubell. “No matter where this hotel was, we would have bought it. We always believed in urban rebirth. We believed in SoHo. We believed in South Beach. We believe that cities do come back and architecture never dies.”

In the 14 years since, Washington has boomed on its own, and Southwest DC—thanks in part to Nationals Park—has begun to show signs of life. But the quadrant has never become known as a particularly art-centric part of town. The Rubells, while talking up their plans for DC, supporting art fairs, and exhibiting their collection around town, have largely stayed on the sidelines.

Now, after years of delays, the couple is poised to break ground on a major project that will preserve the historic Randall Junior High School building, a crumbling brick structure across the street from the Skyline, while creating a new 12-story, 520-unit apartment complex with a restaurant, stores, and affordable housing for artists and low-income residents. The most ambitious element will be a 32,700-square-foot museum to house part of the Rubells’ collection. It will be the largest expansion of their art empire since 1994’s opening of the Rubell Family Collection museum in Miami.

As if to announce their renewed focus on Washington, the couple is mounting “No Man’s Land,” a traveling exhibit of work by dozens of female artists, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, opening September 30. Says associate curator Virginia Treanor: “The Rubells collect this work because they love it and they want to share it with people.”

We always believed in urban rebirth. We believed in soho, in south beach. We believe that cities do come back.

Washington isn’t a blip on most wealthy collectors’ radar. The Hirshhorn Museum and the National Gallery of Art, bound by the constraints of publicly funded museums, rarely show edgy or controversial work. The Hirshhorn held its 40th-anniversary gala in New York last year.

“Curators from the Hirshhorn or National Gallery would rather take a cab to Dulles Airport to look at emerging artists in Berlin than they would take a cab to Adams Morgan to look at emerging artists here,” says Lennox Campello, an artist and former gallery owner. “They don’t do a good job of tending their own back garden.”

Independent galleries, meanwhile, struggle to compete with the pull of Manhattan’s art world. And Washington applies its own pressures. In a rapidly gentrifying city, where nearly every building seems to be turning into an expensive condo, keeping even a guest bedroom that doubles as studio space can be a luxury. The area is seeing more disposable income than ever before, and the new crowd of millennials loves showing up to alternative art happenings like Artomatic or Art All Night, but almost no one is buying art.

The Rubells have a long history of not only buying art but also convincing others to do so. Neither of them came from money or grew up with fine art. Donald was reared in Brooklyn, the son of a postal worker and a high-school Latin teacher. Mera, whose family fled Poland as the Nazis invaded, grew up in refugee camps in Germany before emigrating to the United States when she was 12. “For me to survive at that time was a real miracle,” she says. “No one needed the extra burden of a child.”

The couple’s improbable journey to becoming “super-collectors” started in Manhattan in the 1960s, when Mera, earning $100 a week as a teacher, and Donald, a medical student, began befriending undiscovered artists and buying artwork on $5 weekly installments, a system they still use today with much larger sums.

Their introduction to celebrity came in the ’70s, when Donald’s brother, Steve, became an owner of Studio 54, the disco frequented by Mick Jagger, Calvin Klein, Andy Warhol, and Liza Minnelli. Championing young artists like Jeff Koons, Haring, and Basquiat in the 1980s, they helped summon New York’s SoHo art scene. After Steve’s death from AIDS, Donald inherited his brother’s share of several New York hotels and the family moved to Miami, where they snapped up several worn Art Deco–style hotels and helped transform South Beach into a cosmopolitan playground.

At the heart of their urban-renewal efforts has always been their passion for contemporary painting, sculpture, and photography. By 1994, they had amassed enough work to open a 45,000-square-foot showcase for their purchases: the Rubell Family Collection, housed in a giant former Drug Enforcement Agency warehouse in Miami’s then-sketchy Wynwood neighborhood. They were crucial to the success of Art Basel Miami, an international fair that draws more than 70,000 collectors, artists, and hangers-on each year.

The Rubells’ projects have always had an improvised air, and Mera says their undertaking here is no different. “It wasn’t a grand plan to come to Washington and have a museum away from Miami,” she says. “It felt like there was a real necessity.”

Their motivation, Mera admits, was at least in part their nervousness about what might end up near their hotel. The Randall School closed in 1978 after more than 70 years as an anchor for the African-American neighborhood—in the 1950s, Marvin Gaye sang in the school choir—and later served as a makeshift homeless shelter and artist studios. In 2006, the Corcoran School bought the property for $6.2 million, but financing for a new school and a residential development was lost during the recession. In 2014, the Corcoran itself came apart, a victim of mismanagement and the board’s disagreements about how to dig itself out.

“The Corcoran painted this picture and vision of what this neighborhood could be,” Mera says. “I can’t tell you how disappointing it was when the economic downturn caused that whole thing to collapse. Being across the street, we don’t want to see failure on top of failure there.”

The Rubells partnered with Telesis, a developer in DC, to buy the old school from the Corcoran for $6.5 million. Twenty percent of the apartments will be reserved for affordable housing, including live/work space for artists. The museum, which will occupy the Randall building, is to house part of the Rubells’ art collection.

Says Telesis president Marilyn Melkonian: “It will be a total change and regeneration of that whole part of the neighborhood.”

Some local artists are daring to hope the Rubells will also breathe life into contemporary art in the nation’s capital at large. Mera has been mapping the territory since at least 2009, when she came to DC to select pieces for an auction gala by Washington Project for the Arts in a dawn-to-midnight whirlwind of studio visits called 36 Artists in 36 Hours. The artists she visited were in equal parts excited and perplexed by the experience.

“She was like a little tornado,” says Campello, one of those chosen in a lottery for a visit from Mera. “She looked at my work and sniffed around and asked questions about something I had pinned to the wall, like an old valentine from my wife.” The Campello piece that Rubell put in the WPA auction ended up being bought by a vice president at Sotheby’s, and the artist still feels indebted to her: “I think Mera is going to bring a giant spotlight to the DC area.”

The Rubells could well bolster their real-estate investments by cultivating local artists and igniting the art scene here. Besides her work with the WPA, Mera invited the (e)merge art fair to hold its inaugural exhibit at the Skyline in 2011. Washington fits the Rubells’ pattern of discovering up-and-coming artists where no one else is looking.

Mera says she and her husband limit their budget, refusing to pay the mind-blowing prices for work by some elite artists today. (In May, Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa paid $9.7 million for “Runaway Nurse,” a painting by New York artist Richard Prince, whose career the Rubells helped launch decades ago.) “It doesn’t make it difficult—it makes it impossible,” says Mera. “We have to believe in our hunch, to perceive the talent of an artist even faster than ever before.”

Any spotlight the Rubells shine, however, may shine brightest on their own art. Mera said she wants the museum at the Randall School site to have a local feel, but most of the work will come from their collection. “We don’t buy because we have pity on the artist,” she says. “It’s not a philanthropic activity. We absolutely are engaged in what is compelling to us personally.”

Washingtonians trying to discern the Rubells’ intentions might look an hour north to Baltimore. In 2013, the couple bought the historic 440-room Lord Baltimore Hotel for what Mera calls the “shockingly reasonable” price of $10 million. They’ve spent millions more renovating it and filling it with some of their prized artwork. Mera has gone on studio blitzes in Charm City, too. In 2014, she went there for a weekend, prospecting for another WPA show. Some of her selections ended up going to Manhattan for a gallery exhibit.

“I think she just enjoys being with artists—it’s fun for her,” says Cara Ober, an artist and founder of the online journal Bmoreart, which has partnered with Mera on local events. “The Rubells definitely see themselves as people who see the potential where others don’t.” But Ober cautions that Washington artists shouldn’t presume their paintings will soon be on display in a Rubell property. “I don’t think there’s any illusion by [Baltimore] artists that she’s necessarily going to buy their art.”

Mera says she’s well aware of the challenges Washington artists face. The upside of this city, she offers, is that artists can find well-paying jobs in government or teaching to supplement their income: “An artist who has a daytime job has the freedom to do whatever the hell they want to do with their art. They aren’t desperate to just produce. They make the art they need to make and not just to pay the rent.

“Artists have a way of cutting to the chase and saying things that reach us on a human level that transcends our differences, whether it is country, religion, or sex,” she adds. As for consumers of art, “they find God inside of it. They find the humanity. They find the talent. It changes their life.”

This article appears in our October 2016 issue of Washingtonian.