Two to three days a week, Sharita Thompson and Bernie Demczuk explore the entirety of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture with about 30 DC police officers. The museum lets them in at 6 AM, and they’re usually done at about 3 in the afternoon.

The visit is a new mandatory course for DC’s 3,800 sworn officers, but Demczuk says they’re not trying to teach cops how to do their jobs: “What we said in the very beginning is, we know nothing about policing, but what we’re gonna do is teach you history. That’s what relaxes everybody.”

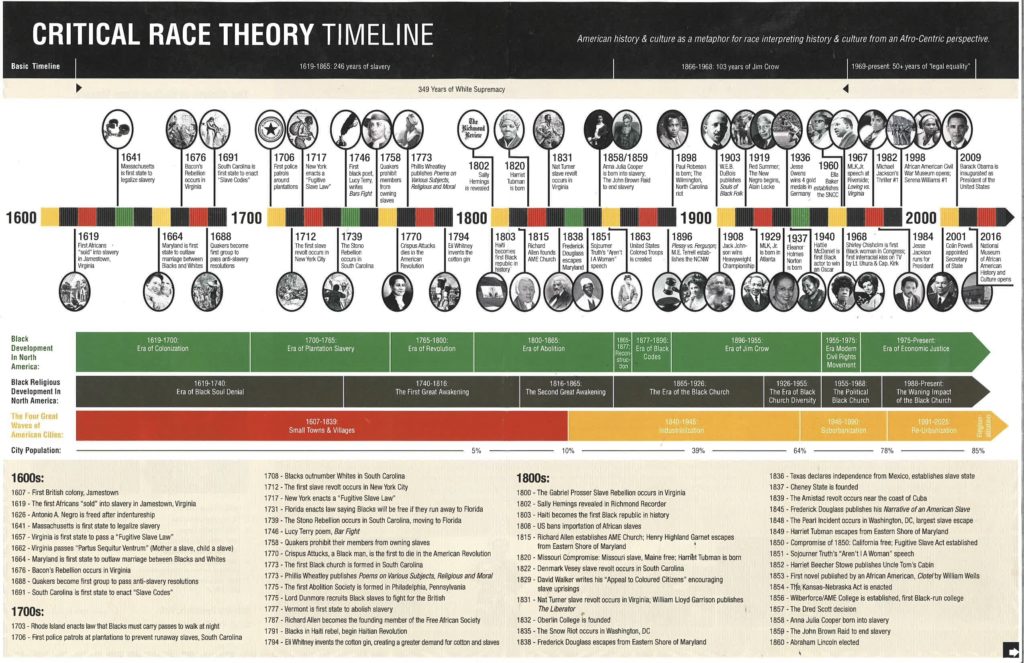

The professors, who both teach at University of the District of Columbia Community College (Demczuk is also the official historian for Ben’s Chili Bowl), start at the lower levels of the museum, with history that dates back to the 1600s. They learn about African-American history both global and local: the great African Kingdoms, the Civil War, Jim Crow Laws, U Street, the fact that Barry Farm is not actually named after the late Mayor Marion Barry.

The thinking behind the course is that cops who dive into black history might better understand the communities they serve. The coursework is animated by critical race theory, which means looking at American history through the lens of African-Americans. So, as Demczuk says, “We’re not really learning it from Thomas Jefferson’s perspective, but from the woman that he had six children with.” DC’s police department says that more than 550 officers and civilian employees have completed the training so far.

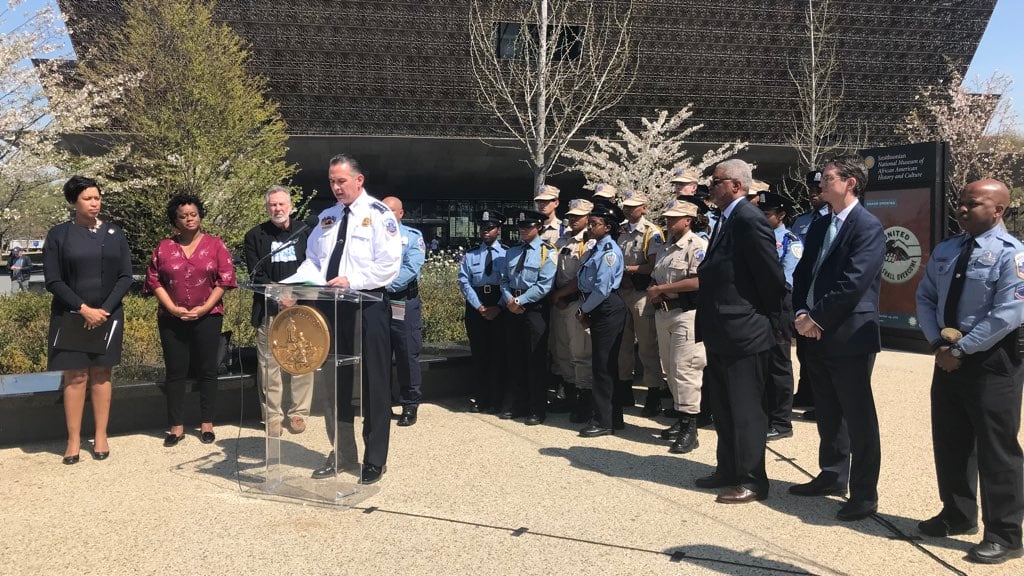

At a ceremony at the museum announcing the program Friday, Mayor Muriel Bowser said the class is part of the city’s effort to strengthen the bonds of trust between police and residents. Police Chief Peter Newsham stood with the mayor. “It’s an opportunity to see how police were viewed by people in the community and come face-to-face with the reality that not too long ago, police officers played an active role in the enforcement of many of the discriminatory and racist laws of the time,” Newsham said.

Demczuk and Thompson say the approach has worked so far. Cops who were initially wary, or hard to read, began to open up. One particular day, Thompson says, an officer repeatedly came up to them to simply say, “I didn’t know. I didn’t know.” DC Police Union Chairman Stephen R. Bigelow Jr. says officers have been learning a lot and also that they’re “already doing a pretty great job.”

Demczuk describes a moment he had with another officer he led through the museum. The man was white, and a 25-year veteran of the force. He cornered Demczuk towards the end of the day, tears in his eyes, to ask one question: Was he a racist? He explained how he’d pass by a white guy standing on a corner in Georgetown, say “Hi,” and keep on walking. But he’d pass by a black guy doing the same thing in Shaw and “Bust him up.” Demczuk says he told the man, “You might not be a racist, but your behavior is racist,” and encouraged him to “teach your younger officers that it’s not fair. If you’re gonna bust people on the corner, you have to have a reason.”