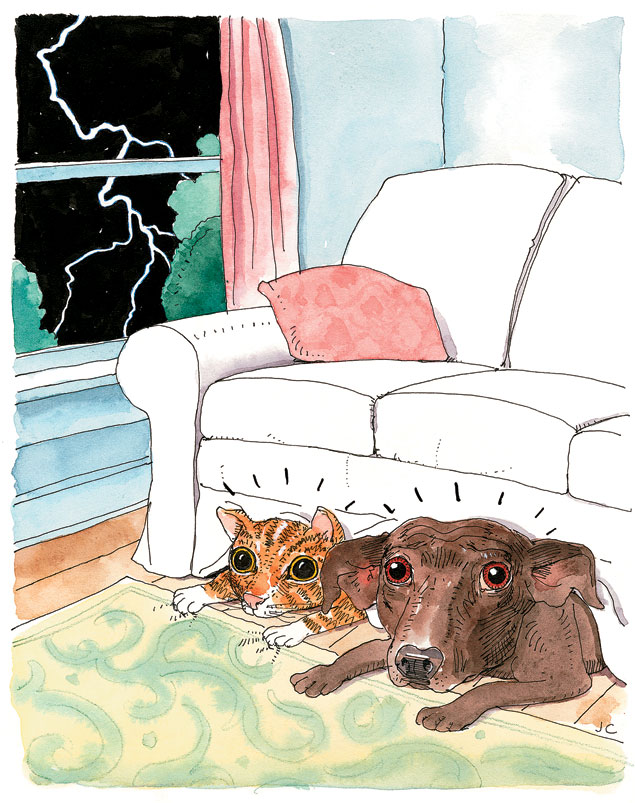

This may be the season for getting spooked, but for many pets, fears and phobias linger long after the trick-or-treaters.

Whenever a storm rolled through Marina and Tim Tignor’s Reston neighborhood, they knew their hound mix, Lilly, would shiver, pant, and drool. Even on calm days, if the wind picked up slightly or the trees rustled, Lilly—convinced a storm was coming—would panic. “I felt so helpless having this animal living in constant fear,” says Marina Tignor.

A number of products claim to ease phobias and anxiety in pets, though reviews of their effectiveness are mixed.

Thundershirt

$39.95

Designed to calm fearful dogs and cats with “gentle, constant pressure.”

Storm Defender

$44.99 to $54.99

This cape’s metallic lining is said to reduce the static-charge buildup animals can sense before a thunderstorm.

Mutt Muffs

$55 to $58

Invented for dogs riding in planes, the earmuffs are now also marketed for pets that fear noises such as thunder and fireworks.

Realizing they couldn’t help Lilly on their own, the couple contacted animal behaviorist Yody Blass, who works with patients throughout the area. Blass estimates that about 40 percent of behavior problems she treats in pets involve fear. Storms are among the most common sources of anxiety for dogs, but everything from household appliances to new babies can cause it.

Lilly began displaying nervous tendencies about a year after she was adopted from a shelter at age one. Rescue animals are often more prone to anxiety because many have suffered abandonment and other negative experiences. But even well-adjusted pets can have phobias—sometimes strange ones.

Blass has worked with animals afraid of particular images on TV, hardwood floors, heights, even grass. Marsha Reich, a veterinary behaviorist in Silver Spring, once treated a dog that fled the kitchen whenever a certain appliance beeped. Reich realized the family’s digital camera made the same noise as the appliance, and the dog associated the camera’s flash with lightning, his true phobia.

Cats and dogs share many of the same fears, though there are differences. Blass says it’s more common for cats to avoid confined spaces and being touched by strangers, while dogs are more likely to suffer from separation anxiety and to generalize their fears—something Lilly started to do as her thunderstorm phobia intensified. “Everything made her uncomfortable,” Tignor says. “She never slept. Little creaks around the house, like when the heat came on, would make her startled.”

Blass suggests desensitizing animals afraid of thunder by playing recorded thunderstorm CDs at gradually increasing volume (a method that she says works only when no actual thunderstorms are forecast). The technique was successful for Lilly, who now curls up next to the boom box when the Tignors play the recordings. They also started giving her anti-anxiety medication.

Reich uses a number of techniques to treat pets. She says that simply distracting a dog from whatever it fears with a Kong toy—a rubber chew toy stuffed with treats—can help. Some clients with dogs wary of strangers have gotten results by keeping a bucket of tennis balls outside the front door for visitors to throw. The exercise can help transform a scary stranger into a fun playmate.

Though Lilly’s fears have eased, Marina Tignor still keeps a close eye on the weather. Addressing her own helplessness and anxiety about Lilly’s phobia has made a big difference. “So much of it is the owner,” Tignor says. “It doesn’t mean that we cause the phobia, but it means we play into it.”

And now that Lilly has calmed down, life is calmer for everyone.

This article appears in the October 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.