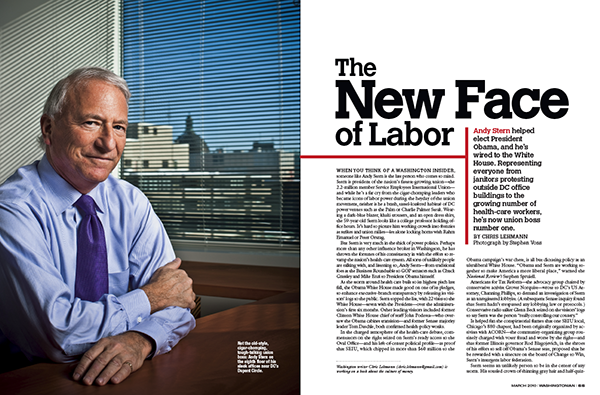

When you think of a Washington insider, someone like Andy Stern is the last person who comes to mind. Stern is president of the nation’s fastest-growing union—the 2.2-million member Service Employees International Union—and while he’s a far cry from the cigar-chomping leaders who became icons of labor power during the heyday of the union movement, neither is he a brash, tassel-loafered habitué of DC power venues such as the Palm or Charlie Palmer Steak. Wearing a dark-blue blazer, khaki trousers, and an open dress shirt, the 59-year-old Stern looks like a college professor holding office hours. It’s hard to picture him working crowds into frenzies at strikes and union rallies—let alone locking horns with Rahm Emanuel or Peter Orszag.

But Stern is very much in the thick of power politics. Perhaps more than any other influence broker in Washington, he has thrown the fortunes of his constituency in with the effort to revamp the nation’s health-care system. All sorts of unlikely people are talking with, and listening to, Andy Stern—from traditional foes at the Business Roundtable to GOP senators such as Chuck Grassley and Mike Enzi to President Obama himself.

As the storm around health care built to its highest pitch last fall, the Obama White House made good on one of its pledges, to enhance executive-branch transparency by releasing its visitors’ logs to the public. Stern topped the list, with 22 visits to the White House—seven with the President—over the administration’s first six months. Other leading visitors included former Clinton White House chief of staff John Podesta—who oversaw the Obama cabinet transition—and former Senate majority leader Tom Daschle, both confirmed health-policy wonks.

In the charged atmosphere of the health-care debate, commentators on the right seized on Stern’s ready access to the Oval Office—and his left-of-center political profile—as proof that SEIU, which chipped in more than $60 million to the Obama campaign’s war chest, is all but dictating policy at an ultraliberal White House. “Obama and Stern are working together to make America a more liberal place,” warned the National Review’s Stephen Spruiell.

Americans for Tax Reform—the advocacy group chaired by conservative activist Grover Norquist—wrote to DC’s US Attorney, Channing Phillips, to demand an investigation of Stern as an unregistered lobbyist. (A subsequent Senate inquiry found that Stern hadn’t trespassed any lobbying law or protocols.) Conservative radio talker Glenn Beck seized on the visitors’ logs to say Stern was the person “really controlling our country.”

It helped fan the conspiratorial flames that one SEIU local, Chicago’s 880 chapter, had been originally organized by activists with ACORN—the community-organizing group routinely charged with voter fraud and worse by the right—and that former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich, in the throes of his effort to sell off Obama’s Senate seat, proposed that he be rewarded with a sinecure on the board of Change to Win, Stern’s insurgent labor federation.

Stern seems an unlikely person to be in the center of any storm. His tousled crown of thinning gray hair and half-quizzical squint make him look like the nerdier older brother of talk-show host Bill Maher. Moving about his office on the eighth floor of SEIU’s modern Dupont Circle headquarters, Stern carries himself more like a laid-back tech executive than a union boss. He might bark out a data point or two when he gets worked up, but it’s usually about a procedural setback in Senate health-care negotiations, not the gruff ultimatums you’d have heard from earlier generations of labor leaders.

Stern is well aware of the differences, in both style and leadership. “You know, it’s a different world,” he says of the labor movement’s diminished sway in the capital’s powerbrokering game. “No one’s saying, ‘What does Andy think?’ as they used to say, ‘What does Sidney think?’ ” Stern points out, referring to the legendary clout of labor leader Sidney Hillman during the New Deal. “We should never forget that the only reason we’re listened to is because of our members. We’re not such brilliant or handsome people on our own.”

Stern was the opposite of a quick study in throwing one’s weight around when he first came to Washington. “Until I became president of the union, I did not do anything related to electoral politics,” he says. “My claim to fame was that I never wore a tie—something I was told I had to start doing once I went [without one] to see Secretary Robert Reich,” Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Labor through 1997. “That’s about how far I was from traditional DC.”

Penetrating the inner sanctum of the White House didn’t sharpen his sense of insiderness: “My first official Washington event was at one of Bill Clinton’s famous coffees. It was the night before his reelection. I thought I was really just going for coffee. I was saying that to someone who worked there—“Gee, it’s so nice that the President wants to have me over for coffee and hear what I think!”—and they told me, no, it was what they called a ‘donors’ event.”

Even now, when he’s held forth as a symbol of Washington clout, Stern keeps an unassuming profile. He lives not far from the Georgetown power eatery Cafe Milano but prefers to schlep much farther up Wisconsin Avenue to the kitschy ’50s-era seafood joint the Dancing Crab. Even there, he grumbles that “they’ve gone a little upscale. But yes, give me a pitcher of beer and a bunch of crabs and sports on the TV and I’m happy.”

Other fixtures of the DC political scene sometimes affect a fondness for more down-market tastes as a pseudo-populist sort of brand management, but Stern seems to have the opposite problem: convincing people he really belongs in Washington. Casting about for a DC-appropriate lifestyle pursuit, he volunteers that “I drive a convertible.” This prompts his SEIU media handler, Michelle Ringuette, to interject that “it’s an American-made convertible”—a Chrysler Sebring.

After 27 years in Washington, Stern says he’s still struck by the city’s deeply self-referential operating grid: “I grew up outside of New York, and in New York money was king—it was all about Wall Street money. In Seattle, being a smart geek puts you at the top of the top of the food chain; in New York, it’s if you’re the manager of a hedge fund or an equity fund. In Washington, there’s just nothing but political power.”

He says one of his struggles is to resist what progressive critics call the “villager” mentality of the city’s power elite: “It’s incredibly hard. Everyone here is focused on this stuff like what the President’s really saying to his staff or what Politico writes. You just have to resist all that—and thank God for our members. Some people in DC live in that world because they were congressmen and lobbyists—because it’s what they know. My world is the 2.2 million people in our union going to work every day.”

Stern says he also is kept grounded in a more fundamental way by a tragedy that shook him and his family to the core seven years ago: the death of his 13-year-old daughter, Cassie, from complications related to spinal surgery. (Stern’s marriage, to environmental and union activist Jane Perkins, fell apart after the loss of the couple’s daughter; they shared custody of their older son, Matt, who is now in art school.)

The shock of Cassie’s death, he says, “reminds you how much we’re moved by love and loss. You come to appreciate how much we truly have to be thankful for in this country. Every day for the past seven years, I feel like I’m trying to forget something, and trying to find the meaning and reason in my life that’s not about getting rich or what other people may think of me—that’s about doing stuff that matters.”

At the same time that Stern professes puzzlement over the currency of power within Washington, he’s a student of a different sort of clout—that wielded in the punishing world of labor infighting. While the right-wing commentariat routinely casts Obama as a devotee of radical community organizer Saul Alinsky’s bare-knuckled philosophy of accruing power in institutions such as school boards and unions, Stern—who came of political age during the New Left’s pinnacle of influence—has followed its spirit, if not its letter, far more closely. Beginning in the early 1970s, with his inadvertent recruitment as a union shop steward during his first job out of college—as a worker in the state welfare department in Philadelphia—Stern rose through the ranks of service-sector organizing.

He moved to Washington from Pennsylvania in 1983, under the tutelage of then–SEIU president John Sweeney, who retired last year as head of the AFL-CIO. Stern soon found his niche in the union’s leadership, taking over its organizing and field-service operations.

That proved to be, in terms of cultivating membership growth, a plum assignment—though it scarcely could have seemed so at the time. The labor movement was in disarray; Ronald Reagan had sent many union leaders into defensive crouches after breaking the federal air-traffic controllers’ union in the wake of its 1981 strike. The Reagan years also coincided with a fundamental—and ongoing—shift in the character of the US workforce, as more employers shed traditionally unionized industrial jobs in favor of lower-wage, non-union service work.

Most labor leaders were caught flatfooted, but Stern heeded the counsel of martyred union leader Joe Hill: “Don’t mourn, organize.” SEIU bucked the traditional organizing methods of the bigger industrial unions and mounted high-profile campaigns to unionize the people many traditional unionists ignored—security guards, janitors, health-care workers. By the early 1990s—when many union memberships were cratering—SEIU had more than a million workers in its ranks.

When Stern’s onetime mentor in SEIU, John Sweeney, left the union’s top spot in 1995 to head the AFL-CIO—a move that was a landmark recognition within labor circles of the new composition of the American workforce—a power struggle ensued. SEIU secretary-treasurer Richard Cordtz had been elected to serve out the balance of Sweeney’s term, through 1996, and pledged to run for a full four-year term after that. But Cordtz—who had been tarred with past allegations of double-dipping from union funds—selected as his running mate Gus Bevona, the scandal-plagued head of a New York local who paid himself $438,000 a year, one of the highest salaries for a labor leader in the country, while the members of his local earned an average of $32,000 in annual wages. Stern announced his own insurgent candidacy in early 1996, provoking Cordtz to fire him for insubordination. But the millstone of Bevona’s dubious associations never permitted Cordtz to galvanize widespread backing among SEIU locals, and he withdrew his candidacy in March 1996.

Stern’s rise may have been serendipitous, but in retrospect it looks well timed. By the second term of the Clinton administration, the labor movement seemed ripe for revival, and Andy Stern—the guru behind the movement’s new mantra of “organizing the unorganized”—was positioned to develop an approach to redressing workers’ woes in the fastest-growing sector of union recruitment.

But as Stern has worked to push the house of labor into the 21st century, older-style labor divisions—and schismatic turns in movement politics—dog his progress. Organizing fights among service-sector unions have stoked questions within labor about Stern’s ability to keep his own members on board—let alone his power to press a labor-friendly agenda within the Oval Office.

A 2007 press appearance touting health-care reform with then–Walmart CEO Lee Scott—complete with a phone-in appearance by Republican California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger—sent Stern detractors into fulminations that would bewilder the Glenn Becks of the world. “The single biggest obstacle to single-payer health care in this country is Andy Stern,” Michael Lighty, policy director for the California Nurses Association—a union locked into one of the state’s organizing disputes with SEIU—told the Nation’s Liza Featherstone at the time.

The Walmart event was one in a series of Stern-backed conciliatory moves toward management that have jangled the nerves of the rank and file. Stern’s union has endorsed contracts with provisions that many rival leaders view contemptuously as giveaways to employers—securing minimal cost-of-living wage hikes in exchange for management pledges of noninterference with organizing drives. And at times Stern has come out in favor of key business-backed proposals—such as tort reform and charter schools—whose benefits to most wage workers are far from clear.

Building off the arguments he advanced in his 2006 book on globalization and the workplace, A Country That Works, Stern contends that labor leaders can’t simply shun strategic alliances with management.

“There’s a certain level of a relationship we need with employers besides just demonizing them,” he says. He cites the health-care fight as a case in point: “All I would say is that if today the pharmaceutical industry, the hospital industry, Walmart, and every big business was against health care, you could all go home and call this thing dead. But the truth is that people built coalitions with AARP and the Business Roundtable and Walmart, then kept an issue alive because it wasn’t completely politicized right from the beginning.”

Stern’s allies in the business world appreciate his more ecumenical

approach to accommodating their interests. John Castellani, who heads the Business Roundtable, joined forces with Stern’s union as well as AARP and the National Federation of Independent Businesses in 2007 to spearhead the Divided We Fail coalition to keep the health-care issue in play before Congress.

“It was amazing,” Castellani says. “We went to an event right after we started Divided We Fail. Bill Novelli [of AARP] spoke first, Andy second, and me third. When Andy finished talking, he’d said everything I was planning to say—that in order to compete globally, American businesses can’t be burdened with these escalating health-care costs.”

Castellani recalls that when he and Stern first teamed up to bring the Divided We Fail message to lawmakers, they provoked more than a few double takes: “I’m sure it was just as surprising when Andy set up the first meeting with [then-senator] Clinton and brought me along as when I met with Senator Grassley and I brought Andy.”

The policy-minded odd couple became so entrenched in the Washington scene that, Castellani recalls, “we both turned to each other at one event and said that if we keep being seen together too much at these things, both our memberships are going to want to fire us.”

Former Senate majority leader Tom Daschle—a key behind-the-scenes player in mapping out legislative strategy for health-care reform—likewise stresses that Stern has been a pivotal figure in combating partisan gridlock and parliamentary inertia: “I think there was a role for someone in labor to provide the unique contribution that Andy has. You needed somebody to take some risks and step up to the plate—it was ready-made for a labor leader.”

Daschle says he was especially impressed by how firmly Stern remained focused on producing results within the legislative process. Even when the Senate version of the bill sacrificed both the public option and the fallback of a broader Medicare trigger backed by Olympia Snowe and other fiscal conservatives, Stern helped keep momentum behind the measure—despite the protests of union membership.

“He clearly was under enormous pressure to publicly agree with Howard Dean and others to just kill off the bill,” Daschle says. “But I’ve had many conversations with Andy over the years about what happens when you fall far short of the goal. Do you kill something or do you use it to build on in the future? He and I have learned the hard way that even though it’s so vastly different than what you’d like it to be, it provides an opportunity—if it does no harm—to build out in future years, and you’ve got to take it and bank it.”

Stern says keeping engaged with the legislative process remains key to the fortunes of the reform effort—and of the Democratic majority. Pointing to the GOP’s recent upset victory in the special election for the late Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat, Stern says he views it as a referendum on “the failure to make change—the sense that the only change out there has been happening to people on Wall Street.”

The lesson of Scott Brown’s Senate win in Massachusetts, Stern argues, isn’t what centrist figures such as Democratic Leadership Council chairman Harold Ford counsel in times of political calamity—to reclaim a pro-business centrist agenda for the Democrats. Rather, it’s to use the party’s congressional majority to deliver on an agenda that will improve the nation’s material well-being.

“I think what people are upset about is the absence of decisions even more than the substance of decisions,” he says. “The people who work don’t get to not make decisions. They don’t understand why people in Washington have that luxury.”

The four years of spadework Stern has spent hoping to produce a broad consensus in Congress also highlights the high-stakes gamble he has launched by tying his union so firmly to the health-care effort. On the one hand, Stern and his union have backed the bill that will create the most enduring legacy of Obama’s first term. On the other, he has placed his leadership clout at the mercy of the deal-cutting legislative process—leaving him open to challenges from fellow progressives that his status as a White House and congressional insider has clouded his judgment and cost his membership what seemed like a golden opportunity to move a labor-friendly domestic agenda through Congress.

One of the most prominent liberal critics of the Senate health-care bill is Stern’s former girlfriend, Jane Hamsher, publisher of the influential progressive blog FireDogLake. A cancer survivor, Hamsher assails the bill as a giveaway to the pharmaceutical industry.

“It’s not even a quarter loaf—or any loaf,” Hamsher says of the Senate accord. “All the deals that could have cut costs have instead been made to support profits for pharma.”

Unlike Stern and other White House allies, Hamsher lays the blame for the measure’s flaws squarely with the Obama administration: “This is the bill they wanted all along. They did it to keep the pharma money out of the coffers of Republican candidates in 2010. This had nothing to do with Congress.”

Specifically, Hamsher charges, the main Oval Office offender is White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel. In December, Hamsher joined forces in a strange-bedfellows alliance with the Stern-baiting GOP activist Grover Norquist, issuing a call for Emanuel’s resignation. Says Hamsher: “From all of the reports, the approach that was taken came from Rahm. It’s got Rahm written all over it.”

Stern professes no special love for the Senate bill: “We shouldn’t believe that this bill solves all our problems, because it has a lot of issues that over time are going to have to change.”

Like Hamsher, he favors the House version of the legislation because it has a “pure public option” and it doesn’t tax workers’ health benefits. But unlike Hamsher, he’s not pointing fingers at the White House—or Emanuel, with whom he’s met almost as many times as he has with Obama.

“You know,” Stern says, “to be the chief of staff for the President of the United States while you’re fighting two wars, having an economic crisis, and balancing the needs of 535 important people in Congress—that is not a job that I would ever want. I believe, though, that he’s tried to do the best he can. If change were a spectator sport, we could all make our own judgments, but for our members, change is a participatory sport, and our goal is not to be analysts of what happened; we want to create change.”

Putting aside the results in the Senate, union watchers fear that the focus on health care has already all but doomed the central item on the labor movement’s legislative wish list: the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), known as “card check” because it would permit unions, which have fought losing rear-guard battles to expand their organizing reach since the Reagan era, to be recognized when a majority of workers demonstrate interest.

Stern bristles at talk that the bill—which he refers to as Free Choice, a shortened form of its feel-good formal title—will suffer neglect at the hands of a Democratic Congress already dreading reelection campaigns. But if you put the question to him hypothetically—card check versus health care, you only get one—he comes down, after some hedging, on the health-care side.

“Any decent country that wants to have basic opportunity for people has to have a health-care system,” he says. “It’s not right that people can die simply because they’re poor, which does happen here all too often. So that’s why we’ve never tried to imagine having Free Choice or financial and regulatory reform or immigration reform or anything that we’re interested in come before health care. It’s just fundamental.”

It’s fundamental to Stern’s union in a more direct way: About half of the SEIU membership is made up of health-care workers, and a big expansion of health coverage will likely create more jobs in the medical sector, meaning that unions such as SEIU are well positioned to keep growing. Certainly, if the card-check bill were to clear Congress together with health care—a long shot—Stern can bolster his standing among labor statesmen by claiming a good deal of credit in both arenas.

But if card check should continue to stall and the conferenced version of the health-care bill should follow the Senate’s blueprint of bypassing both a public option and an expanded Medicare benefit, that could serve as a “trigger” for a government-administered health plan and Stern could be depicted in progressive circles as having bartered his membership’s $60-million birthright in Washington for a mess of pottage.

While Stern can entertain a hypothetical health-care-for-card-check tradeoff, he says that neither workers, Democrats, nor the country can aff

ord to let both measures die.

“If the Democrats, given this privilege by Americans of having the ability to pretty much pass anything they want, squander it, I think it’s going to set this country back to another set of failed policies: a deregulating, privatizing, trickle-down, I-got-mine, so-long-sucker economy.”

To keep up pressure on the pivotal legislators in both fights, Stern made another move coming out of the 2008 election that has endeared him to neither conservatives nor his more tradition-minded critics in the house of labor: He retained a campaign-style staff of 400 full-time workers on the SEIU payroll—called, in a fusion of SEIU and Obama rhetoric, Change That Works. These organizers helped dispatch the corps of activists, sporting SEIU’s purple-and-gold T-shirts—to last summer’s fractious health-care town halls, drawing charges from the right of union thuggery.

And as the Senate’s December health-care vote appeared to pivot on the support of a handful of conservative Democratic lawmakers—such as Blanche Lincoln of Arkansas and Ben Nelson of Nebraska—Stern’s union again swung into activist mode.

“We’ve spent a lot of time in those states,” he says, “mostly demonstrating the support that exists there for health-care reform—in Nebraska, from farmers, from church people, from older voters—an odd coalition, since these aren’t traditionally labor states.”

While the Change That Works effort has netted SEIU a lot of attention in the health-care fight, the union’s broader campaign to mobilize its base behind a pro-labor legislative agenda has plenty of detractors in the union world. One reason you hear Stern talk a lot less about card check these days than he did during the ’08 elections is that, by some accounts, SEIU was never able to effectively galvanize political backing for what was described as the most sweeping upgrade of federal labor law since the New Deal.

Still, even a lavishly supported, well-coordinated EFCA offensive wouldn’t guarantee results, as the health-care melodrama has shown. In today’s Congress, most legislation lives or dies in the Senate—and that body, with its six-year terms and elaborate protocols of legislative deference, was designed to insulate itself from most grassroots appeals. So for all the scorn Stern heaps on the greed of Wall Street and the executives at Goldman Sachs and Bank of America who are cleaning up post-bailout, he seems to reserve a special contempt for Congress’s upper chamber: “People look at the Senate and say, ‘This is embarrassing; we’re bribing people in front of cameras.’ ”

Louisiana’s Mary Landrieu—another on-the-fence conservative Democratic senator—famously moved into the “yes” column on health care after the legislation suddenly sprouted a $300-million outlay in special projects (i.e., earmarks) for states that had recently endured major natural disasters like, oh, let’s say Hurricane Katrina.

“You know, the $300 million that went to Mary Landrieu would be called an illegal contribution if I did it,” Stern sputters. “But within the Senate, it’s just legislation.”

What’s more, he says, “the Senate’s inability to move things has all sorts of unintended consequences. We have the top White House staff constantly negotiating with senators about a health-care bill that—win, lose, or draw—should have been passed in the summer. And we could be talking about what we’re going to do about wages and jobs and holding people accountable who were wrong in the financial crisis. I just think the Senate may become the Waterloo of the first two years of the Obama administration.”

One reason a policy-minded union head like Stern has become so fixated on the ins and outs of legislative procedure is that it’s been a long time since any labor leader has been this close to major legislation.

Apart from the ongoing woes that dog unions in the simple act of organizing workers, labor has been effectively boxed out of many policy debates until recently because the corps of members whom people such as Stern represent has been steadily declining. After its historic merger with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the AFL could claim to represent more than 30 percent of American workers. Now just 7 percent of private-sector workers in the United States belong to unions; add in the public sector and the percentage nudges up to 12 percent—still well under half of the postwar labor movement’s penetration into the US workforce.

SEIU veterans point out that the union has compounded the difficulties that come with labor’s declining demographic clout by keeping a largely pro forma lobbying operation intact in Washington.

Natasha Vargas-Cooper, a former Southern regional coordinator for the union, in reviewing the frustrations of the EFCA effort, notes: “One of the big problems that undermined all this is we were out of power for eight years, and this is one of the things I would have loved to fix—that our legislative affairs group, our lobbying shop, was a f—ing joke. There were three people who worked there, who were basically just rubber-stampers, so that for eight years, if a senator put out a bill we liked, we’d send out a letter that said, ‘Great, thanks!’ And if somebody did something we didn’t like, we’d say, ‘No! Don’t do that!’ ”

These tepid performances didn’t escape the notice of the K Street crowd, Vargas-Cooper adds: “When I was spending time in DC, I’d ask my lobbyist friends, what do you think of SEIU? And they’d say, ‘Well, politically, they have no relationships.’ So that was another thing—even if you have the heat on the ground, even if you’re doing all this stuff on the grassroots level, we still can’t get a meeting with Mary Landrieu. We can just have a bunch of people show up at her office. These were the kind of hurdles that needed to be cleared really fast and really well.”

To make things more challenging, as the stakes have gotten smaller for today’s labor movement, the infighting has grown more rancorous.

Stern has played a prominent role in the mood of factionalism, engineering SEIU’s departure from the AFL-CIO in 2005 to found Change to Win with a clutch of other growth-minded labor organizations such as the United Food and Commercial Workers.

Change to Win’s agenda was essentially to elevate the SEIU model of organizing—recruiting members and pressuring employers via corporate-accountability campaigns that targeted the public image of management—to serve as the industry standard for labor organizing. A no-less-prominent goal of Change to Win was Stern’s vision of a reorganized national leadership for labor—a federation that would streamline smaller, traditional craft-affiliated union locals into bigger operations able to organize across an economic sector. The textbook model of the corporate campaign was SEIU’s Justice for Janitors initiative in the 1990s, which proved influential in shoring up the International union’s power base.

But on balance, the Change to Win experiment has proved disappointing—and the federation may well be on the verge of being folded into a new accord to bring Stern and his allies back into strategic alliance with Richard Trumka, the former United Mine Workers head who last September was elected to succeed retiring AFL-CIO head John Sweeney. Negotiations with the former mother union are delicate, Stern says, but are moving gingerly forward—thanks in large part to the efforts of former Michigan representative David Bonior, an ardent labor advocate who once served as House Democratic whip, to bring both federations to the bargaining table this summer.

“You now have the first chance for every major labor union in the country to be in the same organization,” Stern says. The challenge, he stresses, will be to redress the schism that triggered the Change to Win camp’s defection in the first place—the mandate to keep growing versus focusing on politics and politicians.

“It’s a political-will question,” Stern says. “I’d say John Sweeney was still concerned about people having left the AFL, and his idea was everyone should rejoin it. I think the answer to this is really building something new that takes the best ideas from everybody, building something that works for the 21st century.”

He won’t project a timeline for an AFL agreement but says, “We’re extraordinarily close to solving this issue in a couple-of-stages process. The elections at the AFL just kind of interrupted that [resolution], and the question for the AFL and others is how we get them back on track.”

Stern catches himself and thinks out loud for a bit: “Or do people want to get them back on track? Because we know in many organizations people want sometimes to be the big fish in the smaller pond. And there are many voices in the AFL—not Rich’s necessarily—who have a much bigger voice in a smaller organization than they would in a bigger organization. I’ve argued—and they’ve not liked it—that some of them ought to be

part of a different organization than their own.”

The tentative wooing between Stern’s organization and Trumka’s is sweetness and light compared with the battles SEIU is waging in California. In structural terms at least, these face-offs illustrate much the same quarrel Stern has had with the AFL-CIO brain trust: Does labor dig in for deeper engagement with management/worker conflict at the local level—what Stern calls, a bit dismissively, the “workplace by workplace” approach to organizing? Or does it go bigger and broader—using the more sweeping model of national organizing, across entire industries and sectors, that Stern wanted to institutionalize at the AFL?

While the union’s feud with the California Nurses Association has been a flashpoint in this battle, the main theater of war is SEIU’s bitter fight with a breakaway health-care union called National Union of Healthcare Workers. For all Stern’s talk of the union movement’s mandate to adapt to a 21st-century economy, the NUHW fight is very much an old-school labor power struggle, of the Sidney Hillman/John L. Lewis vintage. The stakes are enormous, with the right to represent California’s huge corps of more than 600,000 health-care workers in the balance—an obvious entry, should the insurgent NUHW prevail, for chipping away at the International’s power base.

And like the 20th-century labor movement’s landmark internal power struggles, this one teems with charges of corruption, betrayal, and collusion with management, coming from both sides and aired with an abundance of personal rancor between Stern and NUHW president Sal Rosselli.

Suits and countersuits have been flying, as have complaints at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), but the basic timeline is as follows: Not long after the SEIU bolted to found Change to Win, Rosselli’s union—then known as the United Health Workers—grew restive over what it felt were unrealistic organizing targets and bids by the International to wrest power from locals. Once the union’s leaders discovered that SEIU had entered into some of the noninterference agreements with state health-care employers, Rosselli, then a vice president on SEIU’s executive board—and hence, union officials point out, a fully informed party to the contracts he has since protested—planned his own mutiny. He consulted with allies and attorneys to launch the new NUHW, taking member databases, electronic communications, local records and (as SEIU charges) $6 million in local union funds.

SEIU also contends that NUHW officials erased many digital records they deemed potentially compromising—a grave charge because, as Stern alleges, the loss of such data has made it impossible to process member grievances and research contract negotiations on their behalf.

Rosselli contends that what began as a fraternal dispute over grassroots policy matters—such as terms of employment and the administration of patient care—spiraled out of control under the power-mad auspices of Stern’s SEIU. Rosselli says NUHW leaders “in a very constructive way started saying, ‘Wait a minute, this is not democratic, it’s not right, for lots of reasons.’ And literally for three years inside SEIU, we tried to internally gain support and insist on democratic processes, with workers deciding their contracts—and we were met with increasing retaliation, to the point where in 2008 I resigned from Stern’s executive committee because there was a gag order on accepting these deals without debate.”

From there, Rosselli charges, the International waged a campaign to paralyze his breakaway organization with classic union-busting harassment. In 2008, SEIU won a ruling from former Secretary of Labor Ray Marshall permitting SEIU to place NUHW locals in trusteeship—i.e., back within the International’s governing structure—finding in the International’s favor on the charges that Rosselli’s leadership cadre had diverted SEIU resources and records into the control of the fledgling union.

But the International hasn’t let up there, Rosselli claims. His union’s officials have been assailed by “charges with the NLRB—charges that we were a company-dominated union, not a bona fide union whatsoever, that we were harassing and intimidating workers—those kinds of charges—forcing the NLRB to do lengthy investigations. And it’s a bureaucracy, right? That’s the worst form of what bosses do—anti-union bosses—to prevent their employees from having a vote.”

For civilian onlookers, there’s a dispiriting “I know you are but what am I?” tone to the donnybrook, calling to mind the decades of union infighting that have contributed so much to the perception of the labor movement’s mounting irrelevance—a fratricidal climate at the top of many big unions that’s nearly as damaging as the business-dictated laws from the Reagan era that have eaten away at the collective-bargaining rights for American workers.

In a straitened economic climate that abounds with all sorts of common enemies—from the investment-bank beneficiaries of federal bailouts to the lawmakers standing athwart the key priorities of health-care reform and card-check legislation—leaders in the fastest-growing sector of labor organizing seem at times to be tearing lustily into each other’s hides.

And that, in the end, is the dilemma that will likely continue to haunt Stern, the first major would-be labor statesman of the 21st century: How does one retrofit the personality-driven, implosion-prone model of industrial-union leadership to do effective battle in an age of neoliberal economic consensus?

This, after all, is an era when corporate managers and financial wizards haven’t merely consolidated power across national borders and within the corridors of our representative government but have also triumphed in what is arguably the only culture war that matters—nurturing the deep-set conviction that business managers and their political retainers are the anointed agents of progress, regardless of how awful their judgment may be or how brutal the mythology of the free market has grown in practice.

That’s in many respects the lesson behind the tightly wound parliamentary accord on health care—and the likely moral of the card-check bill, which doesn’t seem poised to get any serious traction on Capitol Hill before the 2010 election cycle, after which what promises to be a significantly less Democratic Congress would likely consign it to the back burner.

There’s a self-confining character to Stern’s efforts to elevate the union movement’s profile in our national politics, which calls to mind the medieval detention cells that never permitted inmates to stand up completely straight. So long as Stern is compelled to strong-arm smaller unions in pursuit of a more globally minded International bureaucracy, he’ll invite allegations of old-school labor thuggery. And as he fends off such charges in courts and the federal bureaucracy, these conceptions will be widely reinforced in the public’s mind—regardless of whether SEIU prevails on the merits of the case.

If Stern continues focusing on the legislative process inside the Beltway, that too will spur the Sal Rossellis in today’s labor movement to charge that he’s gone native in Washington—that he’s grown so enamored of the White House visits and strategic legislative confabs that he’s forgotten the priorities of the rank-and-file union member. Either way, he’ll remain the most visible, and most easily reviled, face of labor electioneering to the Tea Party right.

Summing up the multiple follies of the punishing health-care fight, Stern says, “Bill Clinton once said it’s better to be strong and wrong than to be right and weak—and I’m beginning to think a lot about that.”

I reply that the motto could double as Harry Reid’s political epitaph—but it occurs to me much later that it could apply with equal force to the labor movement and Andy Stern.