“None of the people who encouraged me to take this job ever told me how often I’d want to quit,” Harriet Tregoning, DC’s city planner, said in a rare calm moment early this fall. “The job of the director of planning is to push for change. No one wants to change.”

Tregoning’s opponents have their doubts. They say she has turned the District’s planning office, a onetime bureaucratic backwater, into a powerful advocate for change.

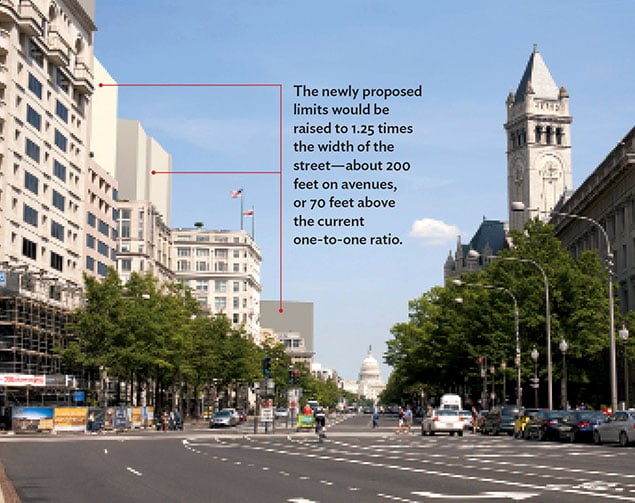

The day before our interview, September 24, her team had released a proposal to allow building heights downtown to go to 200 feet, far above the limit set in the days of Pierre L’Enfant, Tregoning’s original predecessor. Under the plan, certain buildings could rise 70 feet higher than the standard codified in the 1910 Height of Buildings Act. That evening, at the National Capital Planning Commission, she would present the proposal in front of an audience made up largely of critics, who think her plan could ruin the city’s low-slung European character.

Sitting at her dining-room table in the Columbia Heights rowhouse she shares with her husband and their two chows, Tregoning, 53, wore a dark, tailored suit, her brown hair held in place with a band, the better to fit under her bike helmet. Her workday would take her, by bicycle, the 3½ miles to her office in Southwest DC, then to the District Building for meetings with the city administrator and DC Council members, then to the skirmish over the Height Act at the commission.

Tregoning frames the proposal—as she does many of her programs—not as a personal vision for change but as an accommodation to reality. She points out that DC’s population, after decreasing for decades following the passage of home rule in 1973, is growing by more than 1,000 residents a month—most of them young people moving to new neighborhoods west of the Anacostia River or to traditional African-American areas such as Shaw and Eckington. Childbearing families who once fled to the suburbs, meanwhile, are staying, thanks largely to improved schools. “We are getting these middle-class households back at numbers surprising to us,” Tregoning says. “We want to accommodate them.

“The Height Act has served us well,” she says. “We love the streets that are open to light and air. But if the city grows at a rate even lower than its current pace, we will have a shortage of land for development by 2020. It may be necessary to build up.”

The other reality is that the federal government, not Tregoning, makes the decisions about DC’s Height Act. Congressman Darrell Issa, a conservative California Republican who has taken a benevolent interest in DC, broached the matter of the act at a Hill hearing in July of last year, asking the city to review the limits set in the 1910 law.

With limited local control over a burgeoning city, Tregoning points out, Issa’s interest represents an opportunity. “It might be another 100 years before another member of Congress asks that question,” she says.

Many Washingtonians counter that Tregoning has applied her considerable political skills to molding the District in her image. “She has her own set of ideas about where she wants to take the city—it boils down to higher, tighter, denser,” says George Clark, former president of the Federation of Citizens Associations. “She brings a top-down imposition.”

Having the temerity to suggest that office buildings and apartment houses be allowed to bump up a few floors is vintage Tregoning. She’s been challenging the way land is used since the 1990s, first for the federal government and then for Maryland. Now she’s applying her ideas to a city where residents often battle over changes down to the square foot. It’s turned her into a street fighter who often finds herself between warring forces.

• • •

Tregoning first came to Washington as a high-schooler. She remembers marveling at the rowhouses nearly abutting the Supreme Court. “I fell utterly in love,” she says. “I vowed to live here one day.”

Her father, Arthur Hiken, was a sailor serving in occupied Japan when he met her mother, Sumako. The couple moved to Chicago, where Harriet was born in 1960. Two years later, soon after her brother, Alan, came along, Arthur Hiken died, leaving Sumako with two children under age two. “She was a person of great will and perseverance,” Tregoning says of her mother.

Sumako moved her two young kids to St. Louis and found a house three blocks from a library, where Tregoning says she “all but lived.” She started taking classes at Washington University while still in high school and got her degree in civil engineering and public policy at age 20. At the university, she met Michael Tregoning, a banker, then followed his jobs to California and Dallas, in each place working on Superfund policy at the local regional office for the Environmental Protection Agency. After they split up in the early 1990s, she moved to Washington to head the EPA’s waste-policy branch.

Cleaning up land that was already spoiled didn’t satisfy Tregoning. She figured there must be a better way to use land at the outset.

Her awakening as an urban planner began during sessions of President Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development in 1994. The discussions there, about creating communities oriented around walkable town centers, led to a movement that would become known as “smart growth,” and Tregoning became a leading voice. In a country where owning a home in a subdivision embodies the American dream, smart growth was heresy, but Tregoning adopted it as gospel.

At the EPA, she helped convene the Smart Growth Network, a collection of private and public groups, to work out the movement’s basic principles. She rose to chair the Council on Sustainable Development and, in 2000, helped found Smart Growth America, an advocacy group.

Her partner in many of these endeavors was Geoffrey Anderson, whom she met at the EPA and who is now president and CEO of Smart Growth America. They married in 2005. Tregoning and Anderson keep bees at his childhood home in DC’s Brookland, labeling their products Bee-land Honey.

In 1999, Maryland’s Democratic governor Parris Glendening offered Tregoning the chance to put her theories into practice by making her his Secretary of Planning, with the power to review every line item in the state’s $23-billion budget.

Besides helping Baltimore reuse its industrial zones, Tregoning and Glendening relocated a new courthouse and a new campus for the University of Maryland, both planned to be built on farmland outside Hagerstown, to that town’s center. Glendening describes his former aide as a powerful mixture of politician and technocrat: “She used a combination of charm, knowledge, and in-your-face toughness as she needed it.”

When Glendening left office, he and Tregoning founded the Smart Growth Leadership Institute, a policy arm of Smart Growth America. Three years later, incoming DC mayor Adrian Fenty asked Tregoning to run his planning office. By then, she had been living in DC for 14 years, on Capitol Hill and in Adams Morgan and Columbia Heights. “I was utterly excited at the prospect of planning a city I loved,” she says. “At the same time, I was terrified of it.”

If she was, she didn’t show it. In one of her first acts, she halted a plan to remove and redevelop the Florida Avenue Market, a funky wholesale complex in Northeast DC. Her office then proposed a “small area plan,” preserving the old businesses and making way for housing and Union Market, a foodie haven. But despite her occasional fights with builders, Tregoning has rarely advocated against developers—she has mostly asked them to stay within urban boundaries, as befits her principles.

She also has the support of political leaders. Her planning predecessors, Andy Altman and Ellen McCarthy, set the stage for her, under supportive mayors Tony Williams and Adrian Fenty. Vincent Gray backed her when he chaired the city council; as mayor, he kept her on, endorsed her plans, and gave her a direct line to his office. Gray fully supports her proposed changes to the Height Act.

Drivers are more prone to criticize her. Tregoning has proposed wholesale changes to zoning rules for the first time in 55 years. Among her plans, she suggested ending requirements that new buildings provide a minimum number of parking spaces near Metro stops and along bus corridors. The idea brought howls from residents, especially in upper Northwest. When she backed off, urbanists and smart-growth advocates criticized her for compromising.

But the city has continued to squeeze drivers with heavy parking-ticket enforcement, speed cameras, and bike lanes. AAA Mid-Atlantic calls DC’s approach a war against car commuters in which Tregoning is a general. “There’s a parking crisis,” the group’s chief spokesman, Lon Anderson, says. “There are not enough spaces. Then we see these proposed plans to remove parking requirements, and we come to the conclusion that some changes she’s suggesting are just not realistic.”

• • •

I’m almost surprised when, after a recent meeting with Ward 5 council member Kenyan McDuffie—about turning industrial land in his ward from dumping ground to destination—Tregoning accepts my offer to give her a lift. “There’s the impression here that I hate cars,” she says. “It’s not true. I’m not crazy about pedestrian-only streets, either. I think we should share.”

Her feelings about automobiles, she says, are beside the point: “People are going to be driving as much, but they are not going to own cars.” Instead, she believes, Washingtonians will use short-term rentals like Zipcar. Tregoning points out that the District’s newest residents are more likely to have student loans than car loans.

Her goals go beyond shuttling people efficiently from place to place. Yes, she envisions a town with fewer cars, where people walk, bike, and rely on public transportation. When—or if—it’s completed, a new streetcar line she helped champion will connect Benning Road on the city’s east side to Georgetown along the Potomac River. “It will have an impact larger than Metro,” she says.

“I want to make the District more like Paris and London—an exciting, cultural city with a much more diverse economy.”

Her small, pragmatic changes, however, are likely to have a powerful impact on the city’s soul. Take bike lanes. In the African-American backlash against Adrian Fenty that contributed to his 2010 defeat, his advocacy of bike lanes became code for catering to white folks. Many longtime Washingtonians don’t just dislike her changes—they suspect the DC government of using the planning office for social engineering. (Ironically, Vince Gray, voted into office by blacks, has continued to build more bike lanes and supports Tregoning at every step.) Others say the animosity goes beyond African-Americans. In her effort to welcome new, younger residents, one critic claims, she “has lost the heart and soul of older residents of the city.”

• • •

At the first public session on the city’s Height Act recommendations, Tregoning sat behind the curved commissioners’ table wearing a resigned “hit me” expression. After a long day, an errant strand of hair arced over her forehead. “There’s nothing magic about 130 feet,” she told the activists and architects who had gathered at the federal planning commission.

The activists seethed. Raising height limits could allow developers to turn the city into Rosslyn, they said—or worse, Manhattan. “This is the kind of thing that makes me not want statehood,” one woman said.

In the end, the National Capital Planning Commission, a federal body that makes official recommendations on the city to Congress, will likely propose allowing developers to build in the “penthouse space”—the rooftop area now occupied by equipment such as elevator shafts and heating and cooling units—but not beyond. That’s far less ambitious than DC’s recommendations. The commission is scheduled to take a final vote in November and send its recommendation to Congress, together with or separate from the District’s proposals.

If Issa’s committee acts on the recommendations, any changes would then have to pass the House and Senate, which is unlikely. As Tregoning often says, people don’t like change.

After getting stared down for most of the two-hour session, she loads her briefcase onto her folding bicycle, mounts up, and heads to the Metro and a bike ride back to Columbia Heights. “I wasn’t surprised,” she says. “I’m used to getting yelled at at least once a day.”

This article appears in the November 2013 issue of Washingtonian.