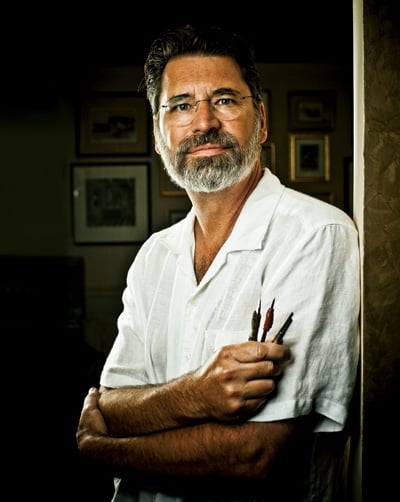

Though few Washingtonians know of him, most of us carry some of Thomas Hipschen’s art every day. His portraits of Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, and Ben Franklin are cut into American history, printed on the front of the $5, $20, $50, and $100 bills.

Hipschen is considered one of the world’s best portrait engravers. “For the late 20th century, he is basically the engraver,” says Mark D. Tomasko, author of The Feel of Steel, a history of currency engraving in the United States.

But when the Treasury Department rolls out a new $100 bill in February, the engraving on the front—a fuller portrait of Franklin—will be Hipschen’s last. The two-centuries-old tradition of hand engraving is fading away. Bank-note artists who cut tiny dots, dashes, and lines into steel plates are putting down their tools and instead using a keyboard and a digital tablet to create images that can be produced in three weeks rather than three months.

The move to digital engraving has raised concern about security and even sparked conflict between the Federal Reserve, the central bank that buys the bank notes, and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which manufactures them, says Michael Lambert, assistant director for cash at the Federal Reserve Board.

Hand engraving has been a security feature of US currency since the early 1800s. Since then, it has been made increasingly complex and intricate in order to frustrate counterfeiters. Hand engraving has remained an important tool for fending off forgeries because engravers’ artistic fingerprints—the subtle differences in style found in the tiny dots and dashes—are hard to replicate. Those idiosyncrasies get lost when the work is done on a computer.

But at the same time that the bureau is phasing out hand engraving, it’s adding anti-counterfeiting technology. The new $100 bill will have features such as a three-dimensional ribbon as well as ink that contains microscopic flakes that shift color with movement. Says Stephen Mihm, a University of Georgia professor who specializes in the history of money: “These innovations are the latest in a game of cat and mouse that has been going on for centuries.”

A magnifying glass held to Benjamin Franklin’s coat—which Hipschen lengthened for the new $100 bill—and to the facial and eye area on the left side of the note, reveals lines that are alternatively heavy, thin, dark, and light. Slanted, tic-tac-toe-like crosshatches with dots inside create depth and texture.

“It’s almost as if the portrait is rising off the paper,” says Gene Hessler, author of five books on paper money and engravers. “A master engraver like Hipschen creates this three-dimensional effect better than anyone.”

Hipschen has spent decades studying engravings—especially those from the 1920s and ’30s—to learn ways to use open space, lines, and dots. “There are a million little decisions because there are a million little dots,” he says. “It’s a very tiny canvas, so all the space has to be put to good use.”

Hipschen’s interest in art was sparked at age eight, when he saw a drawing of a young hare by the German Renaissance engraver Albrecht Dürer in a magazine. “I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen,” he recalls. Hipschen also copied pictures in comic books that his father, a drugstore manager in Bellevue, Iowa, brought home after they didn’t sell.

Hipschen dreamed of studying art in college but knew that with ten children in the family (he was second-oldest), his parents couldn’t afford it. A door to art opened when his cousin Bob Jones, a postage-stamp designer at the Bureau of Engraving in DC, returned home to Iowa to visit and saw Hipschen’s work. Jones knew the bureau was searching for an apprentice and encouraged his cousin to apply.

Hipschen traveled alone to Washington at age 17 with a bus ticket his grandfather had bought. He sketched a still life, competing with dozens of older artists before winning the post. He credits his youth with helping him get the job: “They wanted someone they could mold.”

Hipschen started as an apprentice in 1968, peeling tiny threads of steel off a plate with a pointed chisel, called a burin, to create a seven-cent stamp of Ben Franklin, who designed the country’s first paper money—continental dollars issued to pay for the American Revolution. Franklin used plaster casts of leaves to create lead plates and then print images of the leaves on dollars, because each leaf was unique and therefore hard to counterfeit.

As an apprentice, Hipschen received permission from the bureau to moonlight for the Canadian government to engrave portraits on $10 and $50 bank notes of John A. Macdonald and William Lyon MacKenzie King, the first and tenth prime ministers.

The precision of his work attracted attention among currency experts around the world. He was approached by countries on three continents to engrave their currency, and he received proposals to create illegal engravings. When one man asked Hipschen to copy travelers’ checks, he gave the information to the Secret Service.

Despite his skill, Hipschen’s work long remained anonymous. “The art world and the academic world has largely ignored this area,” Tomasko says. Because currency engraving is a security business, publicity has traditionally been discouraged: “It’s rare to be famous if you are an engraver.”

Over the 37 years Hipschen has spent at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing crouched over an angled, lighted table “digging ditches” in steel, often listening to Beethoven, the reproduction of engravings has evolved.

At first, the finished plates were hardened in molten cyanide and dipped in oil to cool, a technique used in the 1880s. That practice fell out of favor because it was too dangerous. In the 1980s and ’90s, Hipschen continued cutting steel, but the engravings were photo-etched into metal and plastic. By 2000, he was practicing a hybrid engraving method, using both a burin and a computer.

Hipschen was the go-to guy for testing the digital technology. He agreed to put down his burin for a keyboard in 2000 and was sent to Lausanne, Switzerland, to learn to operate digital-engraving technology that could create three-dimensional portraits. Computer engraving involves generating lines, then using digital tools to warp, break, angle, taper, and widen them. When the image is complete, the computer runs a laser that cuts lines into plastic to create a metal plate.

After experimenting with the technology for a few weeks, Hipschen reluctantly declared it a viable option for making US currency. “Being able to artificially create depth was a great leap forward,” he says. “It takes forever to do engraving by hand, but you can do this in minutes. It loses a lot of the character, but I had to admit it worked.”

Repairing a damaged steel plate from an inadvertent slip can take a week, compared with slips in digital engraving, which can be repaired in seconds.

Hipschen’s colleague Ken Kipperman, who engraved the portrait of Alexander Hamilton for the $10 bill that came out in 2006 and is now working on a new portrait of Grant, says a computer can add complexity to engraving. But he warns that anyone doing digital engraving must have training in traditional engraving or else he or she might create bank notes vulnerable to fraud.

“It’s not just a matter of putting an image on a screen,” Lambert says. The Federal Reserve Board insisted that digital engraving be overseen by experienced engravers who know which cuts hold ink best and how to vary line and structure. The bureau says it added digital engraving because the increased complexity of US currency designs “requires a blend of modern technology with the traditional knowledge and skills of our engravers.” It’s continuing to train apprentices in traditional engraving techniques.

Four years ago, after the bureau began expanding its use of computer engraving, Hipschen, now 59, decided to retire. Hand engraving hurt his back and strained his eyes, but he loved it. Computer engraving caused him to suffer carpal tunnel syndrome and simply didn’t feel like art: “I was dealing with equipment I didn’t like, and I wasn’t doing anything original—I was just copying stuff, and I felt worthless.”

Engraving by computer requires that you “just settle for what the program gives you,” he says, “rather than teasing out a perfect resolution of your intention.”

In the 1990s, currency circles were rocked by the arrival of the “supernote,” a nearly flawless counterfeit of the $100 bill, which included a color-shifting ink similar to that on genuine US bank notes and was printed on paper with the same composition of fibers: three-quarters cotton, one-quarter linen. Hipschen says the workmanship on those fakes was so good that they were virtually the same as the real bank notes.

“Almost all counterfeits had some variation, and these did not,” he says. “They were as good as or better than the real stuff, so the banks couldn’t tell the difference. This wasn’t created by a handful of guys in a studio somewhere.”

It wasn’t new technology that tipped Treasury officials off to the fakes—it was the engraving. They noticed that the clock tower on the back of the note was drawn more sharply and with more precision on the counterfeit version, Mihm says. A wide range of evidence pointed to the North Korean government, which denied it was distributing or manufacturing counterfeits.

To thwart such forgeries, the bureau launched new currency designs, ending a drought in new currency that had lasted from 1928 to 1996. Most of the engraving fell to Hipschen, who worked from photographs, slides, and paintings to create larger likenesses of Franklin, Grant, Jackson, and Lincoln for new $100, $50, $20, and $5 bills.

These days, the Secret Service reports that counterfeiters are increasingly turning low-denomination bills into higher-value bank notes. “We are seeing more people taking bleach to bills and upping the denomination,” says Max Milien Jr., a spokesman for the Secret Service, which has been combatting counterfeiting since 1865. Illegally “recycling” the currency paper this way preserves the raised feel of the paper that results when an engraved plate is run through an intaglio press.

Inside the Bureau of Engraving and Printing—a five-story limestone building at 14th and C streets in Southwest DC—a machine with super orlof intaglio 901 on the side operates nearly around the clock, pounding out a loud rhythm that echoes through the money factory. The noise sounds like water dripping, but much louder. Sheets of printed money fly over metal rollers.

This intaglio press coats printing plates with ink, wipes the surface clean, and leaves ink in the grooves of the engraving. It presses the paper and plate together with rollers under tons of pressure, forcing the ink out of the grooves and into the paper to form a relief-like texture.

On the new $100 bill, which goes into circulation on February 10, Hipschen’s portrait of Franklin has been moved to the left to make way for a thick blue security ribbon that creates a shifting 3-D effect. That blue ribbon in a single bank note contains 875,000 micro lenses, each of which focuses to a point over microscopic images. With motion and light flickering through the lenses, the images morph. When the note is tilted, tiny Liberty Bells become 100s. If the note is tilted from side to side, the images move up and down.

The technology, known as “Motion,” was invented by a lab in Georgia and licensed by Crane & Co., the primary paper supplier for the bureau since 1879. Doug Crane, vice president at the Massachusetts-based company, says the technology took eight years to develop. He says the trickiest part was making the blue ribbon one-third the thickness of a sheet of paper.

He says the company keeps all the customized production machines for the technology tightly secured under its own roof, but it has sold the finished product to Mexico, Paraguay, Sweden, South Korea, and Chile.

Crane says Motion would take millions of dollars to recreate and that his dream is that potential counterfeiters “will get a look at this note, just throw their hands in the air, and say, ‘We won’t even try.’ ”

The new $100 bill also contains top-secret “security inks” designed to stymie counterfeiters. These inks arrive at the bureau in an armored car, which transports them from SICPA Securink Corporation in Springfield. SICPA manufactures specialty inks for most of the world’s bank notes, except for those produced in North Korea and Japan. The company, based in Lausanne, Switzerland, has been supplying the bureau since 1983.

Inside the Springfield plant, where the air is heavy with a smell like oil paint, are thick dark-green and black inks, stacks of metal barrels with solvents and oils, giant mixers to combine liquids and pigments, and large tubs of colored powders with recipes attached to the sides. Scientists in lab coats scurry around.

The inks are made from as many pigments as possible to make them complex, says plant manager Richard Overkamp. The company also makes an infrared ink from a transparent pigment. It looks like regular green ink to the naked eye but is invisible under infrared light because it reflects only light waves invisible to the human eye.

One security feature on the upcoming $100 bank note is a “color-shifting ink”—the trade term is Optically Variable Ink—on a small number 100 to the right of the Franklin portrait, which shifts from copper-colored to green when it’s tilted. That ink is made from a thick translucent paste mixed with high-tech microscopic flakes. The flakes contain layers of chrome, magnesium fluoride, and aluminum, which reflect different wavelengths of light, causing the color to shift at different angles, says Thomas Classick, technical director at SICPA.

Because a color copier or scanner reproduces only at one angle, it can’t replicate the color-shifting effect. The bureau uses other security features, such as a thread that glows pink when illuminated by ultraviolet light. A thread with the letters USA and the numeral 100 will appear on the new $100 bill. Additional features are kept secret for use by Federal Reserve banks. They might include electromagnetic fingerprints, which Classick says are detectable only by multimillion-dollar machines in the central banks.

Cracking anti-counterfeiting technology usually takes crooks just a generation, according to Mihm, the University of Georgia history professor: “I’m not aware of any anti-counterfeiting technology that has lasted more than 20 years. Counterfeiters have always caught up. When anti-counterfeiting technology comes out, it puts a stop to counterfeiting until someone finds a way around it.”

Mihm thinks would-be counterfeiters of the new $100 bill are already angling to get their hands on the Motion technology: “They’ll reverse-engineer it and figure out how to make it.” He says adding new technology to a bank note is often viewed as an easy solution, but it can actually be more dangerous: “If counterfeiters can crack the code of the technology, they can produce a much better facsimile or imitation than they could while working in old-fashioned ways.”

Hipschen worries about the loss of the human touch with the move to digital engraving. Each engraver makes and sharpens his or her own tools, so that one might make more of a ragged edge when going around a turn or an angle. “The nuances are very subtle; if you lean a tool one way or another, you will have a different quality,” he says. The artists’ individual styles may not be visible to the untrained eye, but a forensic bank-note specialist can find the differences.

“You can recognize who has done an engraving by the dots and dashes,” Hipschen says. “If you are working in someone else’s style, it looks forced, not natural or correct. You can make a very accurate reproduction, but they are never quite the same.”

Adding technology to bank notes dares counterfeiters to create forgeries with computers rather than artistry, Mihm says: “It’s partly the challenge that seems to invite people to do this. Putting out the new $100 is like saying, ‘Bring it on. Hit us with your best shot.’ ”

This article first appeared in the October 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.