Environmentalists say they’ve sensed a green tipping point.

“The debate about climate change in the scientific community has been over for ten years,” says Mike Tidwell of Chesapeake Climate Action Network. “The debate in the media ended right around Hurricane Katrina.”

Environmental activists say that lawmakers invite them more often to testify—and House speaker Nancy Pelosi ordered an energy audit of the Capitol. Big companies are partnering with conservation organizations. Venture capitalists are investing billions in clean-energy projects.

Al Gore organized Live Earth, a star-studded, seven-continent concert event that made ecoliving ecocool. The green glitterati frequently visit here to lobby lawmakers. Brad Pitt is working with Global Green USA on rebuilding a sustainable New Orleans. Robert Redford, Leonardo DiCaprio, and James Taylor sit on the Natural Resources Defense Council’s board. A board member of Conservation International? Harrison Ford.

“Celebrities have been particularly helpful in getting out the message that the stakes are high but there are solutions,” says the NRDC’s David Hawkins.

Doing the work in the trenches are members of Washington’s environmental establishment—lobbying Congress on renewable energy, fighting for international bans on overfishing, kayaking local rivers to track pollution. They’ve taken some of their battles to the Supreme Court—and won.

We asked more than a hundred environmental activists to name the region’s biggest changemakers. We haven’t included some obvious names—for example, Will Baker at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation is well known for doing everything he can to clean up the bay, while Patrick Noonan, founder of the Conservation Fund, has helped protect more than 6 million acres of land in the United States. We dug deeper. Sometimes all it takes is an individual with a dream to make a big difference.

Here are 30 Washingtonians working to make the region—and the world—a greener place.

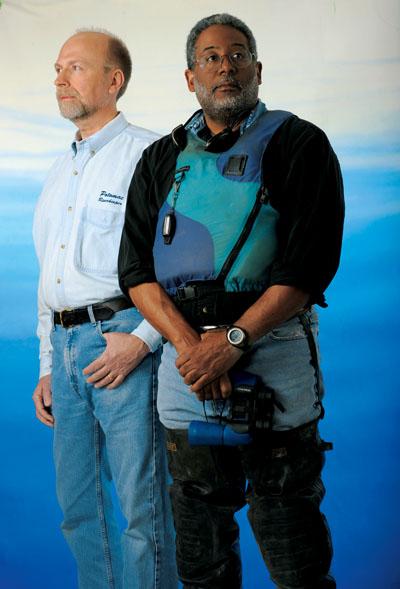

Fred Tutman, 50; Ed Merrifield, 60; Michele Merkel, 40: Waterkeepers

“The river needs an advocate.”

In 1999, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. cofounded the Waterkeeper Alliance to empower citizens to protect their local waterways. It was created to support waterkeeper programs, including 14 in the Washington region; among them are programs for the Patuxent and the Potomac.

Individuals are attracted to the job from all walks of life. Merrifield, the Potomac riverkeeper, is a retired chiropractor. Tutman, the Patuxent riverkeeper, spent 25 years in various mass-media roles including as a media consultant. Merkel, regional coordinator of Waterkeepers Chesapeake, spent about five years trying to get power plants to lower emissions. She’s hoping to organize all 14 waterkeepers into a single powerful voice.

Describe a typical day. Tutman: I get up at the crack of dawn and patrol my waterway by boat. Sometimes I fly above the river in a Cessna. I’m looking for bad dumps, illegal practices. I’m in courtrooms, in administrative hearings. I’m writing, planning, planting trees.

What is the biggest problem facing local waterways? Merkel: One is apathy. Everyone knows what the problems are and what we need to do to fix them, but every year the same news is reported. People have expected government to take care of the problem. It’s no longer just about seeing oysters or crabs at historic lows; you’re seeing waterman towns disappearing, whole ways of life.

What drives you? Merrifield: When the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, they wrote into it the goal that we’d be putting zero of our pollution into the water by 1985. We haven’t come close to that. That’s what drives me—getting to 1985.

Lisa Heinzerling, 47: Law professor

“I could not have written a better opinion.”

Heinzerling, who teaches at Georgetown University Law Center, helped win the landmark Supreme Court case Massachusetts v. the Environmental Protection Agency in 2007. The case held that the EPA has the power to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act.

Why is this case important? It means cars, power plants, all sources regulated under the Clean Air Act can be regulated by the EPA. One argument had been that the state of California can’t regulate greenhouse gases from cars because the EPA can’t. Now that argument goes away.

What went through your mind when you heard the decision? It’s a big deal to have the Supreme Court open an opinion with a paragraph talking about climate change. Justice Stevens wrote that “a well-documented rise in global temperatures . . . [has] resulted from a significant increase . . . in the atmospheric concentration of ‘greenhouse gases’ . . . .” That was huge.

How did you celebrate? I had dinner with my family. I have a 9- and a 12-year-old, and they had to deal with me working weekends. They were happy to have me home. Everybody got to say, “We won!”

Daniel Juhn, 42: Geographer

“Data is advocacy.”

Juhn, director of Conservation International’s regional analysis program, flies over the most threatened parts of the world, dangling out of a low-flying Cessna, to track deforestation. One of Juhn’s reports was part of the data that inspired the president of Madagascar to triple his country’s conservation lands.

What drives you? The feeling that we’re in a race to save rapidly disappearing habitats and species. When I wake up in the morning, I know exactly what I’m going to do that day.

How did you get involved in this work? I spent a lot of time in international development and public health. I used to work with Doctors Without Borders in Mozambique, and I did an indigenous-rights project in the Brazilian Amazon. One begins to sense that there’s a tie between human well-being and intact ecosystems.

What has been your greatest challenge? Not being able to move as quickly as one would like. There are about 5,000 endemic orangutans in Sumatra. Because of the pressures for wood in post-tsunami reconstruction, we’re seeing large swaths of forest disappearing. We predict that at this rate there might be ten years left for this orangutan. Once those habitats disappear, it’s game over.

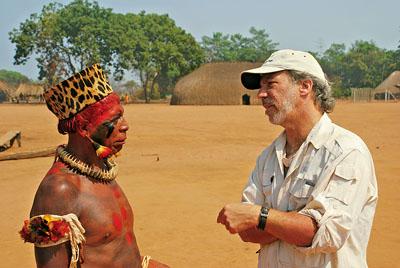

Mark Plotkin, 52: Ethnobotanist

“When you turn on the TV and see the rainforest up in smoke, don’t think it has nothing to do with you.”

Plotkin cofounded the Amazon Conservation Team in 1995 to empower indigenous tribes to protect their rainforests. He believes that cures to diseases may be found in threatened plants.

Why have you devoted your life to protecting the Amazon? The greatest threat to our species is drug-resistant bacteria. Even in a biotech age, 80 percent of our antibiotics come from Mother Earth. We have only a tiny fraction of what’s in the Amazon. I work with shamans who can’t read or write but have treatments for diseases we don’t.

What do you consider your greatest accomplishment? ACT has mapped 41 million acres of rainforest and partnered with 26 tribes. I’m most proud that the tribes have accepted me as a family member.

Who is your “green” mentor? The Indians—these guys will lay down their lives to protect the forest.

Hervé Houdré, 50: Hotel manager

“I consider myself a citizen of the world.”

Houdré, general manager of the Willard InterContinental, is pushing to make the hotel the most environmentally friendly in Washington. In 2006, he released a 70-page treatise called “Willard InterContinental: The Next 100 Years,” coining the term “sustainable hospitality” and outlining his vision to reduce the hotel’s carbon footprint. Just changing its urinals to waterless has saved tens of thousands of gallons of water a year.

What drives you? I was born in an inn in the Loire Valley, and it was on the river. It was very beautiful, very peaceful, and at my back were beautiful forests. I would love my great-great-grandchildren to enjoy the same quality of life.

What has been your greatest achievement? In many hotels, you’re encouraged to reuse your towels to conserve water and detergent. We don’t keep the money we save. We’re donating it to help clean the Anacostia River.

What’s next? We’re putting in every room a document that offers tips on what to do on vacation to be environmentally friendly. For example, when you’re staying in a hotel, why leave the air conditioning on if you leave in the morning and come back in the afternoon?

Can a hotel have an impact? We have so many powerful people staying with us, like the CEOs of major companies. If they see everything we do, they may take it home and implement it in their company. Then we’ll make a difference.

Jessica Miller, 30: Activist

“I’ve been arrested twice. It was definitely worth it.”

When she’s not writing online newsletters and action alerts as a Web editor at Greenpeace, Miller takes environmental action into her own hands. In 2004, she scaled a 700-foot smokestack at a power plant in Pennsylvania. Last year she was on a Greenpeace ship in the Amazon trying to disrupt shipments from an American company illegally clearing rainforests.

Why do you believe in this kind of activism? In DC, we all talk about the changes we want to see and how to get there. For me, this is a little less conversation and more action.

Do you consider yourself an extremist? If it’s extreme to risk my life to save this planet, then yes, I am.

What’s it like to be on a smokestack? It’s really hot. It’s very dirty. While I was on this huge chimney that was burning coal and emitting toxic chemicals, I was also looking out over the Allegheny River and into the hills of Pennsylvania.

What about you surprises people? In 2002, I was working in the fashion industry in New York. At night, I was helping organize activists. I found out about the job at Greenpeace, and my life took a 180.

Bill Browning, 46: Green-building consultant

“Buildings are responsible for 40 percent of carbon-dioxide emissions.”

Browning helped launch the US Green Building Council, a group promoting sustainable building and design, now with 13,000 members. His firm, Bright Green Terrapin, pulls together developers, architects, and other experts to create “sustainability teams” for large projects, including an ecofriendly community of 20,000 homes in Arizona and the green town of Haymount, Virginia.

What is a green building? It means looking at building materials—the environmental cost, where they come from. Thinking about energy, daylight, ventilation, stormwater runoff. Every significant rain, raw sewage runs into the Potomac. You don’t want to worsen the issue.

What is the Washington area’s greenest building? Sidwell Friends middle school. It was given platinum status by the US Green Building Council.

Can older buildings be ecofriendly? I did an environmental retrofit of the White House during the Clinton administration. The Pentagon is looking at green standards. Buildings adhering to the Green Building Council’s standards average 32 percent energy savings over code—we’re talking about millions of tons of CO2 being saved from the atmosphere.

Jerome Ringo, 53: Green-economy advocate

“Poor people can’t afford a Prius.”

Ringo, who worked at a petrochemical plant for 20 years before becoming a conservationist, is president of Apollo Alliance, a coalition of businesses, unions, and conservation and faith groups working to create a green economy he believes will bring up to 5 million new jobs, many to the underclass. He’s former chair of the National Wildlife Federation’s board, the first African-American to hold such a title at a major conservation group.

What are “green-collar” jobs? In the coming years, there will be jobs in industries like solar panels, wind energy, biofuels. The production of these alternatives is going to require trained personnel. That’s why we’re working with labor groups. They have the mechanisms in place to train people.

Why is the environmental movement so, well, white? In the ’30s and ’40s, many conservation groups were formed by hunters and fishermen. It was a predominantly white, male movement. Over the years, it’s become clear that we all breathe the air and we all drink the water, so we should all be involved. Unfortunately, the minority community is still not a major player. Poor people are more concerned with next month’s rent than with the depletion of the ozone.

How do you change that? We have to figure out how to make renewable energy more affordable. We should make polluters pay for what they’re putting into the atmosphere and use the money to educate people and to provide subsidies to help them do something about it.

What drives you? Dr. Martin Luther King said that to achieve civil rights, it would take a broad coalition of people from all walks of life. I believe that energy rights can be achieved the same way.

Scott Nash, 43: Entrepreneur

“Once you go organic, it’s hard to go back.”

In 1987, Nash founded My Organic Market, or MOM’s, a chain of local health-food stores that has become a $30-million business. Nash offers employees $3,000 toward the purchase of a hybrid car. He powers his stores with wind energy. Three years ago, he cofounded the Clean Energy Partnership, a green chamber of commerce with about 60 members, to inspire other companies to follow in MOM’s low-carbon footsteps.

What drives you? Building the business has been exciting, but after 20 years it can get a little old. About four years ago, I decided MOM’s had to be more than big. I wanted it to change the world.

How are you doing that? Last year we kept 60 percent of our solid waste out of the landfill. We give all of our Styrofoam peanuts to UPS stores to reuse. We compost. We recycle batteries. Twice a year, we check customers’ tire pressure to make sure their tires are properly inflated so they don’t waste gas.

How have MOM’s customers changed? When I opened my first store, it was pretty much hard-core hippies. Now you see more soccer moms.

Is Whole Foods the enemy? When it opened in Rockville in the ’90s, it almost put me out of business. I had to give my one employee my motorcycle because I was out of money. But it exposes people to natural foods. They end up walking through our doors.

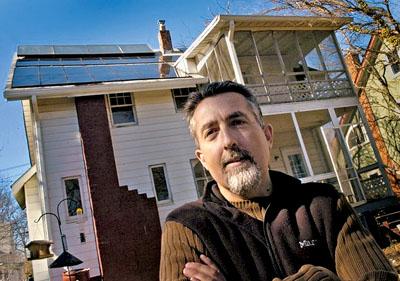

Mike Tidwell, 46: Writer and activist

“The debate on global warming is over.”

Every other month, Mike Tidwell, who founded Chesapeake Climate Action Network—a leading voice on the local impact of global warming—opens up his Takoma Park home to the public, teaching guests about his low-carbon lifestyle.

What is a low-carbon lifestyle? I generate a fraction of the greenhouse gases produced by the average American. I heat my house with a corn-kernel stove. I power my house with solar panels. I walk or take Metro or drive a car that gets 50 miles to the gallon. I’m a vegetarian; when you stop eating meat, you reduce the amount of CO2 in the air. Meat production is very energy-intensive.

Why do you think, as you’ve said, that some people think global warming is a hoax? It’s denial. When you let the reality of climate change fully in, there’s a whole host of moral responsibilities.

How could global warming impact the Washington region? The EPA says top Maryland agriculture yields will drop by 40 percent because of shifting precipitation patterns. The Potomac River is going to get a foot of sea-level rise. Something really big is coming.

Stephanie Reynolds, 38: Oyster wrangler

“Sometimes I’m in a business suit. Other days I’m in a wetsuit.”

Reynolds is a fisheries scientist and lobbyist for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The bay lost much of its oyster population in the past two decades as a result of increasingly poor water quality. Thanks to Reynolds—and her army of volunteers—10 million oysters are now thriving in the Maryland part of the bay.

Oysters taste good, but why else are you trying to bring them back? The population today is about 4 percent of its historic level. Oysters are important because they filter pollutants and their reef structure serves as habitat for other species. They’re the bay’s best natural filter.

Are they hard to farm? If you have a well-selected site, oysters do quite well. I was in the bay this morning pulling up some oysters that we planted last year, and they looked terrific. But they’re not spawning on their own and making a baywide difference in the population.

Why not? It’s funding. It’s political will. We don’t have enough reefs to make a difference. It’s very expensive and labor-intensive.

What are you proudest of? We have hundreds of people in Maryland and Virginia who serve as oyster foster parents. We give them oysters when they’re a few months old, and they keep them in cages for a year and tend them. Then they bring them back and we plant them on the oyster reefs.

What’s the best part of your day? Being on the bay. I grew up sailing here, and I love this body of water. I really believe it can get better.

David Friedman, 37: Engineer

“Our cars and trucks produce as much global-warming pollution as the entire economy of India.”

Friedman, an analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists, has developed a prototype for an SUV that gets about 35 miles a gallon.

If it’s possible to have a fuel-efficient SUV, why haven’t automakers developed one? Why weren’t there seat belts in cars? Why weren’t there air bags? They were all technologies that science showed could save lives. It took the government to step in and require those changes.

What differences in an SUV’s design are necessary for fuel efficiency? None. It would cost more up front, but you’d have the same size, the same acceleration, better safety. This isn’t rocket science; this is auto mechanics. We have the technology to dramatically improve the fuel economy of cars and trucks.

What’s been your greatest achievement? I helped get tax credits for hybrids passed. It puts a smile on my face when I hear someone talking about how they saved a couple thousand dollars because of that.

What do you drive? A Honda Civic HX. I get about 38 miles a gallon. Every couple of years, we rank automakers. Honda is consistently the greenest.

Stephanie Meeks, 43: Land and water conservationist

“We’ve become a broker for conservation.”

Meeks, acting president and CEO of the Nature Conservancy, is working to reinvigorate the 57-year-old organization with an ambitious goal: By 2015, she plans to help double the number of conservation lands worldwide.

Why is the Nature Conservancy focusing so much attention abroad? The majority of the world’s biodiversity is outside of the United States. The world is expanding its footprint in terms of industry, housing, and agriculture. Biodiversity loss is accelerating.

How can the Nature Conservancy help? We have a robust fundraising program. We’ve been working on how to leverage that asset for our international program. We’ve asked every state program to adopt a fundraising goal for conservation work outside the United States. For example, our program in Colorado has developed a relationship with Mongolia because they share a grassland type.

How has the Nature Conservancy stayed relevant in a field flooded with conservation groups? We’re not competing with those organizations; we’re recognizing what role the Nature Conservancy can play. We’re bringing groups together.

What place do you love most? I grew up in Colorado, and I have to say it’s still one of my favorite places. When I want to recharge, that’s where I go.

Craig Venter, 61: Geneticist

“When we first proposed this research, people thought we were crazy.”

Venter, the biologist who raced the government to sequence the first human genome, wants to end America’s dependence on foreign oil. After taking his yacht on a three-year research trip around the world, he says the ocean may hold the key to alternative fuel sources.

Why did you decide to study the ocean? My major form of recreation is on the water, boating and fishing and sailing and surfing, so I may be more aware of the ocean than most people. After sequencing the human genome, I had the privilege to look around at what I thought were the most important problems facing humanity. What we’re doing with fuels I consider number one on the list.

Any exciting developments? We recently announced a major deal with BP that will look at microbes for converting surface carbon, including oil and coal, into much cleaner-burning natural gas.

Do you consider yourself an environmentalist? Not a card-carrying one. I like jet travel and cars and motorcycles and boats. I want to get to a place in science so we don’t have to go backward in society—stop traveling or communicating—because of the way we’ve been generating energy.

What drives you? Curiosity. Wanting to make a difference. Wanting to apply the best of science to help humanity survive.

Richard Carroll, 55: Wildlife biologist

“When you make yourself still, it’s amazing what appears before you.”

Carroll, managing director of the Congo Basin, Namibia, and Madagascar division of World Wildlife Fund, has been protecting gorillas in the Congo Basin for more than 20 years. Today, thanks in large part to Carroll, almost 40 percent of threatened forests in that region have been set aside for conservation.

Why have you dedicated your life to studying these animals? When you’re walking through the forest and you see a gorilla and catch his eye, there’s a recognition that we’re not all that different. If we can’t protect our nearest relatives, then we’ve failed ourselves.

What’s it like to hang out with a 400-pound silverback? It’s wonderful—and it can be scary. Sometimes one will come bursting out of the undergrowth and begin beating his chest. You can’t stare. You go slowly to the ground and pretend you’re feeding on leaves and act like a monkey. I’ve had a silverback right in my face for 30 minutes, smelling his hot, acrid breath, until he was satisfied that I wasn’t a threat.

What would surprise people about your work? Me. Many people think that I look like a gorilla. I have a full beard, bushy hair. I want the gorillas to recognize me when I go back.

Courtney Sakai, 36: Oceans advocate

“I like to say that blue is the new green.”

Sakai, a senior campaign director for Oceana, has become a fixture at the World Trade Organization in Geneva, where she’s been lobbying for an end to global fishing subsidies that she says encourage overfishing. Last year, she convinced the House and Senate to pass resolutions calling for international bans on the subsidies.

Why are you spending so much time on this issue? If we don’t change our practices, fisheries will be gone within decades. Those are years, not centuries.

Is there any good news? If we make these changes, fish populations will rebound.

What are you proudest of? Within 18 months, we’ve taken an issue that had no attention and brought it to the front page of the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, and International Herald Tribune.

Do you have a personal connection to the ocean? I grew up in Hawaii, and my family was always big on fishing. I used to think, “Let’s catch a fish and cook it for dinner.” Now I think twice about that.

Should we eat fish at all? Yes, but choose wisely. Buy fish that are abundant, caught sustainably, and low in mercury content, like Alaskan salmon or farmed clams, mussels, and oysters. Avoid species that are overfished or caught using ocean-damaging gear—like shark, orange roughy, and Chilean sea bass. A guide to sustainable seafood can be found at oceana.org /north-america/publications/seafood-miniguide.

Richard Cizik, 56: Evangelical Presbyterian minister

“I had a second conversion.”

Cizik, vice president for governmental affairs at the National Association of Evangelicals, broke rank with the religious right when he announced that he believed global warming was human-induced. He’s influencing millions with his biblical message of “creation care”—Christians have to care for God’s creations, including Earth.

What changed your mind? I was confronted with the science behind climate change in 2002, and I realized what the Bible was teaching all along. Genesis 2:15 says to watch over the earth and care for it.

What has been your greatest obstacle? In the religious community, there’s the perception that climate change is a latte-sipping, endive-munching, Prius-driving, East Coast, Ivy League idea.

What are you proudest of? More than 100 leaders—heads of megachurches, relief organizations, and Christian liberal-arts colleges—have signed the Evangelical Climate Initiative. Evangelicals need to know that science is not the enemy.

Is it a sin to pollute? In Revelation 11:18, the Bible says God will destroy those who harm the earth. One has to think: Is that me?

Cate Magennis Wyatt, 46: Historic preservationist

“If we choose to do nothing, our communities will look like Anywhere, America.”

Wyatt, a former real-estate developer, is working to conserve a swath of land from Gettysburg to Monticello that she calls the Journey Through Hallowed Ground because of its Civil War battlefields and historic landmarks. Wyatt is hoping to have the region designated a National Heritage Area, making it harder for developers to build housing tracts and shopping centers.

What surprises people when you talk about your project? Every single elected official is in support. We have meetings in the community and ask residents what they want their town to look like in 30 years. People thank us for helping maintain the area’s cultural fabric.

What does “Anywhere, America” look like? It has no beauty or character. Unmindful development is not necessary.

What’s your vision for the future? I want to start a socially responsible land-management trust. Investors won’t make the highest rate of return, but they’ll know that the trust is purchasing land that will be eased or conserved.

Paul Faeth, 49: Clean-water advocate

“Clean water is an issue that’s pretty much ignored.”

Faeth is executive director of Global Water Challenge, a program that brings together corporations such as Cargill, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, and Dow to fund sanitation and clean-water projects in the developing world.

Why are you asking private companies for help? There are 1.1 billion people without access to safe drinking water. Diarrhea is the second-leading cause of child mortality under age five. There are not enough grants or aid to serve everybody. You can get amazing things done when you work with companies.

What are you proudest of? In 2005, Congress passed the Water for the Poor Act. We were able to get big companies to help out on the lobbying side. For example, the CEO of Dow wrote letters to the heads of relevant committees to get them to appropriate funds. We helped get another $300 million for poor people in the developing world.

Are you actually installing water pumps? We are, but we’re also trying to answer bigger questions. Is it possible for villages to own and operate their own systems? Can you make loans available to these communities? Why do the poor pay 12 times as much for water as we do?

What drives you? My religion is important to me. This is a calling.

Sam Enfield, 58: Wind-farm developer

“My objective is to displace as much coal and nuclear power as possible.”

Enfield, who works with PPM Atlantic Renewable, was instrumental in developing four of the first five wind farms serving the Washington region. Mountaineer Wind Energy Center in West Virginia has 44 turbines; at capacity, each produces 1,500 kilowatts, enough to meet the energy needs of 500 homes.

Why do you believe in wind energy? I went to a hearing in 1979, and three atmospheric scientists were talking about CO2 levels and global warming. It made a huge impression on me. Wind is the most cost-effective bulk renewable we have.

What impact does a wind farm have on the power grid? Whenever we’re generating and injecting power into the grid, another generator, like gas or coal, is backed out.

What are some of the obstacles you run into? Wildlife issues are important. The Mountaineer wind farm went up in 2002, and we found significant numbers of dead bats under the turbines. We’ve had to try to figure out why it’s happening and how we might solve it. In the east, we’re putting turbines on mountains. It’s the only place where there’s enough wind to generate cost-effective power. Some people don’t like that. And some people don’t like the sound. You hear the swoosh.

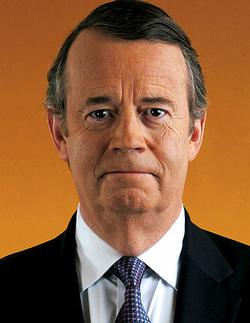

David Hawkins, 64: Lawyer

“We are not too late to avoid the worst.”

Hawkins, director of the Climate Center at the Natural Resources Defense Council, is a leading voice in the fight against climate change. He helped write the Clean Air Act, which required, among other measures, lower automobile emissions and sulphur-dioxide scrubbers on coal-fired power plants.

Why have you dedicated your life to these issues? It stems from childhood experiences in the outdoors—my family took walks almost every weekend in the countryside in Connecticut. Also, in law school I worked at a big Wall Street law firm and found that profoundly unsatisfying.

What has been your biggest achievement? I spend a lot of time in the business community, and one result is the US Climate Action Partnership, a group of ten large corporations—including GE, Shell, Ford—and four environmental groups. We’re sitting down with companies that are the biggest sources of emissions and agreeing on reducing that pollution.

Twenty years from now, will our lives look different? It may not look all that different on the surface. There will still be lots of cars on the road, but the cars will go further on a gallon of fuel. We’ll have houses with appliances that are substituting intelligence for fossil fuels.

Lee Bodner, 39: Marketer

“The environment has a marketing problem.”

Bodner, executive director of the nonprofit marketing firm EcoAmerica, worked with the EPA and the Department of Energy to develop the Energy Star label. Now EcoAmerica is helping “brand” the environmental movement.

What do you mean when you say the environment has a marketing problem? A light bulb went off for me after the 2004 elections. You had 85 percent of voters saying that they wanted to protect clean air and clean water, but political choices didn’t reflect that. That’s a marketing issue.

How are you changing that? The movement has been relying on cause marketing—the idea that “if you only knew more, you’d care.” But it needs to employ consumer marketing. If you’re selling blue jeans, the consumer doesn’t have an inherent need for your product. You have to give people a reason to want it. If we could harness consumer demand effectively, we’d push the pace of environmental progress.

Any interesting developments? We launched a program aimed at college presidents to green their schools. The idea is that they’d set goals to eliminate greenhouse gases. We didn’t know what kind of interest we’d get, but 360 schools signed on, including the University of Maryland. Another thing we’re doing is ranking colleges based on environmental performance to show how these factors make students’ lives better: Does the school offer locally grown food? Can you get around campus without a car? Is the indoor and outdoor air quality good?

Verna Harrison, 55: Foundation head

“My life has been devoted to the bay.”

Harrison is executive director of the Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment, a small but mighty foundation that will award $7.2 million this year to projects promising to clean up the Chesapeake Bay. Harrison was assistant secretary of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources for 20 years.

What do you mean when you say the bay is being suffocated? We have agriculture and air pollution hitting the bay, which causes nutrients to grow in the water. The nutrients feed algae, and the algae shut off the light that causes underwater grasses to grow. That drives the fish out and increases toxic blooms.

What needs to be done? We have to reduce pollution from agriculture and increase the capacity of small watershed organizations including waterkeepers.

Who is your “green” role model? Keith Campbell, a Baltimore investment banker who donated a large part of his fortune to start the foundation in 1999. He understands that individuals can be part of the solution.

Ken Cook, 56: Researcher, writer, activist

“I consider myself a muckraker.”

Cook is cofounder and president of the Environmental Working Group, an organization of scientists, former journalists, and researchers who pull together reports to expose what the government isn’t telling Americans. The studies often land on the front page of the Washington Post.

What are you proudest of? In 1996, we did a series of studies on the risks of pesticides to children that helped prompt the Food Quality Protection Act. We’ve stopped many bad things from happening. People come to us and say, “I need someone who can make this issue pop.”

What drives you? I used to joke that 80 percent of what got me into the office in the morning is that I was just pissed off. The way we’re treating our health and our planet is outrageous. That’s still true.

How do you get people to listen? The most important element is surprise. Surprise someone and you’ll open his mind.

Eric Schaeffer, 53: Lawyer

“Power plants have money to burn.”

After 12 years at the EPA, in 2002 Schaeffer blew the whistle on lax enforcement of the Clean Air Act. That year, he founded the Environmental Integrity Project, a group fighting air pollution one power plant at a time.

Why are you focused on power plants? There are about 400 coal-fired plants in this country—some of the dirtiest are in Maryland—and they’re big polluters. If you enforce the law, you can clean these plants up.

Is it hard for a plant to clean up its act? No, but it’s expensive, which is why they resist. When we brought a case against Hatsfield’s Ferry Power Plant in Pennsylvania, it was the fifth-largest emitter of sulfur dioxide in the country. Ultimately, it agreed to put a scrubber on, which removed 95 percent of the sulfur dioxide going into the air.

What motivates you? I recently visited a plant in Texas. It was 98 degrees and the flares were smoking, and it smelled like rotten eggs. I drove with the windows down. When I’m arguing about clean-air standards, I want that smell in my nose.

Sonja Fordham, 43: Marine biologist

“Sharks need all the advocates they can get.”

Fordham, who works at the Ocean Conservancy, is known as the “shark lady” for her work protecting sharks. She spends a lot of time lobbying the European Union on international bans on shark finning—what happens when fishermen net a shark, slice off its fins, and toss it back into the sea.

Why sharks? They’re in serious trouble. Despite their fierce image, they’re extremely vulnerable to overfishing. They grow very slowly and have a small number of young, so their populations can be easily depleted and can take decades and sometimes centuries to rebound.

Why are you spending so much time in Europe? Spain is one of the top shark-fishing nations in the world. It has too much influence on conservation action in the EU. We’re trying to raise awareness with the other member countries. The EU is very powerful. Without them, the United States can’t get very far.

Have you ever come face to face with a shark? I went cage-diving off South Africa and saw great whites. I got to snorkel with whale sharks off western Australia.

Do you relate to sharks? Sometimes we all feel underappreciated. Sometimes we feel fierce.

Mark Spalding, 47: Foundation head

“I don’t typically eat my clients.”

Spalding is president of the Ocean Foundation, which awards grants to restore the world’s oceans. The money is collected from donors and corporations; recent pledges total more than $90 million.

Is it hard to raise money to protect oceans? Sure, because you sit on the beach and the ocean doesn’t look different. There’s no image that conveys the urgency. But it’s dramatically changed.

What’s the most pressing issue in the Mid-Atlantic? Fishing is diminished. Cod, tuna—they’re much harder to catch. We’re fishing down the food chain for things we used to consider trash, like dogfish or skates. On this coast, we pretty much wiped out the shark population. You take the top predator out, you get more skates and rays and they eat more scallops and other things we like to eat.

Living in Washington, how do you get your ocean fix? I’m always traveling for work. Last year, I spent time in St. Kitts on a coral-reef project. I was in Malaysia looking at how to protect leatherback sea turtles.

What’s the best part of your job? The ocean is more resilient than any other terrestrial system we know. If we give it a chance, it can recover.

Brent Blackwelder, 65: Lobbyist

“The tax code tends to reward the dirtiest polluters.”

Considered a grandfather of the environmental movement, Blackwelder is president of Friends of the Earth, an organization working on issues locally, nationally, and in 70 countries. He’s been lobbying Congress for 38 years to improve the nation’s environmental record. In 1973 he helped found American Rivers, leading to the protection of more than 160 rivers nationwide.

What is the environmental movement doing right, and how is it failing? We’ve expanded the number of parks and protected areas. We’ve done some remarkable things in protecting natural resources. But the government is still subsidizing dirty-energy technologies of the past like coal, oil, and gas.

Were you born an environmentalist? I got a master’s in math, a PhD in philosophy, and I planned to teach. Then on April 22, 1970, I went to the first Earth Day, and Friends of the Earth had a table. I was outraged by what I learned.

What are you proudest of? We lobbied the World Bank to be more environmentally sensitive. They were financing dirty-energy projects. Those are federal tax dollars. We helped avoid some real boondoggles.

Not everyone in Washington is working to save the planet. Who's not? For a look at ten people who environmentalists say are standing in the way of change, click here.