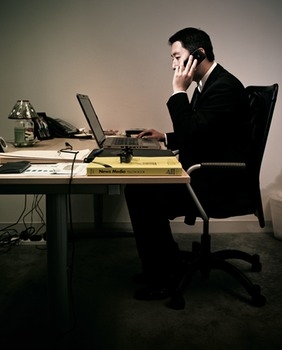

Kurt Bardella launched phase two of his comeback plan on March 17. Early that morning, he banged out a blog post about the earthquake in Japan. Bardella e-mailed the piece to his contact at Politico’s Arena, an online forum for political commentary, where it was soon published.

The exercise felt familiar. From his apartment in Arlington, Bardella wrote at the same desk that—until three weeks earlier—he had often used to blast press releases about his boss. His Fox News Sunday coffee mug remained beside the computer. His photograph with George Stephanopoulos was still on the wall. The complete DVD set of The West Wing was stacked beneath the TV. Only the couch—which now had a pillow and blanket for daytime napping—suggested change.

The loss of his Capitol Hill job had been devastating. “Work for him was his wife, his girlfriend, his mistress—it’s what he lived for,” says former colleague Jenny Spradlin. But for many who witnessed Bardella’s rise, his public implosion wasn’t a shock. “It was like he was driving a Metrobus at full speed while working on his BlackBerry,” says a Republican press operative, who, like many others interviewed for this story, didn’t want his name included.

For three days in late winter, the political news cycle whipped around this 27-year-old press aide. The controversy devolved into a Washington soap opera, ensnaring a press-obsessed congressman and a chorus of brand-name journalists.

Bardella’s firing revealed an essential truth about Washington in 2011. While the 24-hour news cycle has rewritten the playbook for generating media attention in Congress, it has left unchanged the cardinal rule for press aides: Never let yourself become the story.

After he was fired, Bardella approached his mentors for advice. This was survivable, they said; he hadn’t broken any laws. They laid out a strategy: Apologize, disappear for a while, and return with humility. Bardella, however, wasn’t wired to go underground.

Instead he made appearances in congressional offices and Republican hangouts, telling everyone: “The worst part is behind me, and I’ll get through this.” If he kept his message tight, Bardella figured, people would be more likely to repeat it verbatim. After five years of managing congressional reputations, Bardella was now applying his trade to himself.

Next, he measured his level of radioactivity by becoming a regular contributor to Politico’s Arena. When his reappearance generated only a handful of snarky blog posts, Bardella felt he was ready for phase three. He contacted a friendly journalist from a publication far outside the Beltway—Mark Walker of the California-based North County Times, Bardella’s hometown newspaper—and offered an exclusive interview about his demise. If he were ever asked about it, he could refer to that story. “And yes, I did the interview on a Friday and it ran on a Saturday as Congress was going into a recess,” Bardella says.

Kurt Bardella arrived on Capitol Hill with a background unlike that of most congressional staffers. As an infant, he was found on the doorstep of a church in Seoul, South Korea. He knows nothing about his birth parents. “If I ever met them, I’d say, ‘Thank you for giving me up’ and ‘Can I see your medical history?’ ”

Bardella was adopted by a young couple in Rochester, New York. His new father worked as a security guard at an office building while his mother pursued a degree in literature at the University of Rochester. When he was three, Bardella’s adoptive parents divorced. Bardella lived with his mother and spent alternating weekends with his father. He attended a Catholic school and served as an altar boy. In second grade, classmates began teasing him for “looking Chinese.”

“I wasn’t hurt; I was just confused,” he says. Bardella’s mother explained why he was different.

While working part-time at a school for special-needs students, his mother met a fellow University of Rochester undergraduate. They married and had two children. When Bardella was ten, his stepfather was admitted to a PhD program in San Diego; the family piled into the minivan for the cross-country move. Leaving his father behind was painful. “I cried all the way to California,” Bardella says.

The family settled in Escondido, a community of 148,000 residents tucked into the valley 30 miles northeast of San Diego. They found a two-bedroom apartment and enrolled the children in public schools. Bardella got comfortable quickly, making friends, earning solid grades, and becoming an LA Lakers fan.

Maintaining a relationship with his father back in Rochester grew difficult. At first, Bardella’s father visited California each year to celebrate his son’s birthday. But birthday visits became birthday phone calls. Eventually, his father stopped calling. Bardella blames his father’s struggle with money. “He ended up being an absentee father—not because he didn’t want to be there but because he didn’t have the means to be there,” he says. It’s been 11 years since they last spoke.

At Escondido High School, Bardella occasionally wore a shirt and tie and was active in classroom discussions. “He would argue with teachers because he thought his way was correct,” says a former classmate.

“He had a lot of confidence—a little cockiness—but he still made a good impression.”

Reading and writing were his strengths. Susan Crandall, an Escondido High teacher, says Bardella once took part in a speech contest as a member of the school’s academic decathlon team. While his teammates spent weeks rehearsing, Bardella wrote his speech in the car on the way to the competition. He took first place. “He was always good with words,” Crandall says.

In the cafeteria at lunch, Bardella would pull principal Steve Boyle aside to talk politics, a subject that had interested him ever since he wrote a report on Bill Clinton in eighth grade. “He understood things on a different level than most other kids,” Boyle says. Bardella moved easily between social circles, comfortable with bookworms and athletes.

Teachers and administrators could tell he was going places. They nominated him for the Escondido Youth Commission, an advisory board formed partially in response to the 1999 shootings at Columbine High School in Colorado. “Of all the students who became involved, [Bardella] was the most enthusiastic,” says Lori Holt Pfeiler, Escondido’s mayor at the time.

Bardella once went before the Escondido City Council to request public funds for a high-school charity event. “He stood out,” says former councilman Jerry Kaufman. “He had a lot of confidence—a little cockiness—but he still made a good impression.” Bardella’s efforts convinced the council to appropriate the money, Kaufman says.

Although Bardella’s parents were liberal, his experience with the Republican-led council pulled his views to the right. As his civic engagement increased, his name began appearing in print. “I don’t disagree with [members of the Escondido City Council] arguing about the issues, but there were personal attacks going on,” Bardella, then 17, told the San Diego Union-Tribune in a story about the council’s political dysfunction.

Midway through Bardella’s senior year of high school, his stepfather landed a well-paying job in Tehachapi, a California town about 200 miles north of Escondido. Although the move put Bardella in a new school, Escondido High allowed him to walk with his old classmates on graduation day. When Bardella returned to the school for a visit that spring, students wore paper ties in his honor. “He was such a hard worker and an inspiration to his friends,” says classmate Jon Upson.

Students called it Kurt Bardella Day.

After graduating from high school in 2001, Bardella planned on attending the University of California at Davis before heading to law school. But at the end of a summer internship with a state legislator, he was offered a full-time job. By then, Bardella felt he had outgrown his high-school buddies. “They’re going to a keg party, and I’m focused on the California budget crisis,” he says. So he passed on college and went right into the workforce.

Bardella served two years as a political grunt, answering phones and attending community events. Then in 2003, a millionaire congressman named Darrell Issa spearheaded the recall of California’s Democratic governor Gray Davis. The recall effort prompted a local CBS affiliate to beef up its political coverage. A producer contacted Bardella to gauge his interest in a career change; Bardella pounced. He became the station’s political point man, writing scripts for newscasters and tracking down lawmakers for interviews. But the path to elite TV journalism is a long slog through remote American outposts. Bardella had no interest in that.

When San Diego mayor Dick Murphy resigned amid a public-finance scandal in 2005, Bardella returned to politics, joining Republican businessman Steve Francis’s mayoral campaign. Although Francis lost, Bardella’s work caught the attention of Steve Danon, a public-relations consultant who worked for Francis. During the campaign, Danon hired Bardella.

Danon was impressed. While most young staffers clocked out at 5 pm, Bardella often stayed until 10 or later. As the only employee without a college degree, Bardella believed he had to work that much harder, Danon says. “There was a little bit of an insecurity in Kurt,” he says.In late 2005, the firm landed a new client: Brian Bilbray, a former San Diego County supervisor running for Congress. Bilbray joined a field of 14 Republican candidates looking to fill the seat vacated by Randy “Duke” Cunningham, who had resigned after pleading guilty to accepting $2.4 million in bribes.

At 23, Bardella emerged as a key member of the campaign’s media team. He drafted press releases, set up interviews, and pushed the message. At 11 one night, Bardella saw a misreported item in an online article about Bilbray. He called the publication’s night editor and had the mistake corrected before it appeared in the newspaper the following morning.

Bilbray defeated his Democratic opponent with 49 percent of the vote. Danon began assembling a team to run the Washington office. Although he was inundated with résumés, Danon offered the press-secretary job to Bardella.

Bardella was thrilled to be heading to Washington. While browsing through a thrift shop during his junior year of high school, he came across a VHS three-pack of The West Wing. He bought it and was hooked from the first episode. Although he knew The West Wing was only a TV show, it shaped his perception of the nation’s capital. “It was an idealized version that I had, that this place is where some true impact happens,” Bardella says. He says he thought, “It would be really amazing to be a part of that life.” He left California on July 5, 2006.

From the moment he arrived here, Bardella was spellbound: the Lincoln Memorial, the Mall, being at the center of the political universe. “I was in awe,” he says.

“It was like he was driving a bus all full speed while working on his Blackberry.”

Still, Bardella wondered if he could make it. He didn’t have a college degree or national political savvy. “I was terrified,” Bardella says. “I wasn’t sure how I would stack up against the best of the best.”

At after-work cocktail parties, Bardella formed his image of Washington success. “You go to those receptions [and] you see those people who, when they walk through, everyone knows who they are,” he says. “I was like, ‘I wonder how it feels to be one of those guys.’ ”

Bardella’s idol was George Stephanopoulos—the former Bill Clinton spokesman who turned his White House experience into a political-journalism franchise at ABC News. When Stephanopoulos walked into a cocktail party, people noticed.

In high school, Bardella had devoured Stephanopoulos’s autobiography, All Too Human: A Political Education. In it, Stephanopoulos compares his childhood altar-boy service to his backstage role as a political aide, because it allowed him to go behind the curtain of a church service. The sentiment resonated for Bardella, who had liked being an altar boy in Rochester for the same reason.

When Danon learned of Bardella’s regard for Stephanopoulos, he suggested Bardella contact him. Bardella sent Stephanopoulos an e-mail. Like he’s ever going to respond to me, he figured. I’m a nobody.

To Bardella’s surprise, Stephanopoulos replied with an invitation to the ABC News studio in Washington. They met for 20 minutes, and Stephanopoulos signed Bardella’s copy of All Too Human: “Good luck with your political education.”

Bardella considered the encounter a one-time thrill. He was stunned to hear from Stephanopoulos several months later.

Representative Bilbray had been active in the congressional debate over illegal immigration, which was emerging as a big national issue. The congressman’s Southern California district was close to the Mexican border, and immigration policy had been the central theme of his campaign. That made Bardella a good contact for journalists reporting on the issue. Stephanopoulos wanted to know if a Republican resolution opposing the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007 would pass the GOP conference. The act, which would have provided a pathway to citizenship for as many as 20 million undocumented immigrants already living in the United States, faced sharp criticism from the left and the right. Bardella assured Stephanopoulos that the measure would pass.

Shortly after their conversation, Bardella watched Stephanopoulos’s appearance on ABC’s World News Tonight. Stephanopoulos predicted that Republicans would vote in favor of the resolution, citing congressional sources.

“Just like that, I had become a source,” Bardella says. “I was flabbergasted that this was live ammunition we were playing with.”

An hour later, Republicans did vote in favor of the resolution.

Shortly after Bardella got to Washington, his mother asked him a troubling question: “What if I told you your [step]father was having an affair?”

While attending a college reunion in Rochester, Bardella’s stepfather had begun a relationship with a former classmate. He later admitted to the affair and begged Bardella’s mother to take him back. Only after reconciling did he leave for good.

“I was heartbroken for my mother,” Bardella says. He no longer speaks to his stepfather.

Bardella already had insecurities tied to his estrangement from his two previous fathers, and his stepfather’s infidelity only made things worse, says Karen Arant, a high-school friend’s parent whom Bardella calls his “second mother.” Bardella used his career to paper over self-doubt. His attitude reflected “a bit of ‘I’ll show you—I’ll be someone in spite of this,’ ” Arant says.

Bardella immersed himself in his Capitol Hill job. He saw Bilbray’s work on border-security issues as a chance to raise his boss’s profile. “My goal for Brian was to make him the leading voice on immigration,” Bardella says.

At Danon’s PR firm, Bardella had learned one way to generate media attention: “Just pitch.” He began bombarding cable news outlets with requests to put Bilbray on the air. The inquiries were so relentless that one producer began screening calls and blocking Bardella’s e-mails. “He’s the only person on Capitol Hill whose e-mails I have blocked,” the producer says.

Getting the congressman on TV was harder than Bardella expected. Despite Bilbray’s track record on immigration, he remained a mostly unknown member of the minority Republican Party. At one point, Bardella suggested to Danon they change tactics.

“You can either continue to pitch or you can find another job,” Danon told him. Bardella kept at it. He formed relationships with television producers and bookers. When Fox News had a last-minute cancellation, it asked Bilbray to fill in. Bardella sent the clip to other news shows, and momentum built from there.

From his own experience with the tight deadlines of TV news, Bardella believed that he had seven minutes or less to respond to a press inquiry before the network moved on to another lawmaker. So he made sure always to be available. “He has his BlackBerry next to his head when he sleeps so if it rings he can wake up and answer it,” Danon says.

If a producer called and Bilbray wasn’t available, Bardella would contact other congressional offices on the network’s behalf. “I became the guy that if you call me, you’re gonna get a body to fill that chair. Period,” he says. “He was fantastic,” says a cable-news producer.

His Capitol Hill contemporaries noticed. “He had a reputation for being able to get his boss on TV,” says one GOP spokesman. “When you work for a rank-and-file member, that’s often how you are judged.”

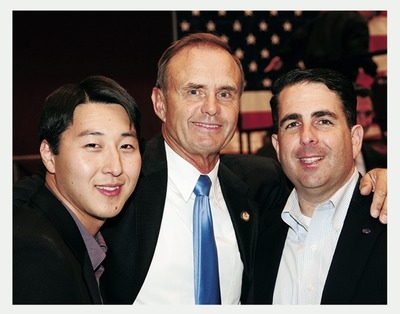

When Bardella began working in Congress, Bilbray’s office was next door to Representative Darrell Issa’s. Because both congressmen were California Republicans, their staffs considered each other family, Danon says. Bardella began popping by his neighbor’s office and developed an easygoing relationship with Issa, one of the most press-hungry members of Congress. “Darrell would see me and we’d always just joke around like, ‘I’m getting more press than you are,’ ” Bardella says.

At one point, the two offices held a friendly competition to see who could get more media attention. The outcome remains in dispute. “They would say they got more [press] hits,” Bardella says. “Well, if you had an AP story [that runs in 1,000 publications], you can’t count that 1,000 times. That’s cheating. I’m like, ‘I killed you guys in TV. I smoked you guys.’ ”

“He had a reputation for being able to get his boss on TV. When you work for a rank-and-file member, that’s often how you get noticed.”

Bardella’s career became his identity. “He kept telling me how good he felt, that he had found his niche, that this is where he should be,” says Jenny Spradlin, a former Bilbray aide. Danon believed Bardella had the tools to go all the way to the top. “You could be a White House press secretary someday,” Danon told Bardella.

After a year and a half with Bilbray, Bardella took a press-secretary position in December 2007 with Olympia Snowe, a Republican senator from Maine. He returned to Bilbray’s office less than a year later but remained eager to ascend the party ladder, telling Dale Neugebauer, Issa’s chief of staff, that he’d always wanted to join their team.

Bardella had long related to Issa’s life story. The congressman grew up in a blue-collar household in Cleveland before striking it rich as a car-alarm manufacturer. It was Issa’s voice warning you to “please step away” from automobiles that were outfitted with his Viper alarm system. Issa’s rise was not without controversy: In the 1970s and early ’80s, he pleaded guilty to a gun charge and was indicted on car-theft-related charges. He also was suspected of burning down a building he owned in 1982 to collect insurance payments.

In early 2008, Issa caught a lucky break. Virginia congressman Tom Davis, then the highest-ranking Republican on the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, announced he wouldn’t run for reelection that fall.

Under the right leadership, Oversight and Government Reform can be one of the high-profile committees in Congress. The panel has used its subpoena power to haul everyone from baseball slugger Mark McGwire to former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan before lawmakers.

Although ambitious, Issa was still a political benchwarmer. A leadership position on this committee could help him to develop a brand. With Representative Davis’s endorsement, Issa won the support of his GOP colleagues and became the ranking Republican member on the Oversight Committee.

Around that time, Dale Neugebauer asked Bardella to swing by the office. When he arrived, Bardella found Issa packing for an overseas trip.

“Hey, congratulations,” Issa said.

“What are you talking about?” Bardella responded.

“Oh, you haven’t talked to Dale yet?” Issa said. “Act surprised when you talk to him, but I just told your boss I’m stealing you.”

Bardella was ecstatic. This is going to be fun, he thought.

Congressional-leadership aides see the network of press secretaries working for rank-and-file lawmakers as a farm system. They scout staffs for promising aides who could succeed at a higher level. In the House of Representatives, press aides follow a well-worn path to the top: From the office of a rank-and-file member, they might move up to a committee, and then—if they have skills and energy—to a leadership staff.

Bardella played smart internal politics, getting together with the spokespeople for key Republican Congress members and dutifully following up after the weekly message meetings with leadership staff. Senior press operatives saw potential. “He had been identified early on as someone who had a great deal of talent,” says one former senior GOP communications aide. “But there were always concerns.”

Even as he raised the profiles of the Congress members he served, Bardella earned a troubling reputation. Though he once felt insecure about his lack of formal education, he found that many in Washington were impressed he’d made it to Capitol Hill without a college degree. He came to see his “school of hard knocks” diploma as an asset. While working in Snowe’s office, he often bragged about not having wasted his time in college, according to a Republican press aide.

On Facebook, Bardella trumpeted his professional goal: “Become the Press Secretary to the President of the United States.” Although more than a few political press secretaries share this objective, putting it in writing on the Internet was considered presumptuous. “It’s one thing to be ambitious,” says a former senior GOP spokesman. “It’s quite another thing to publicly state, ‘I have ambition.’ ”

On Facebook, Bardella trumpeted his professional goal. “Become the Press Secretary to the President of the United States.”

Through his network of Facebook friends, Bardella promoted himself. A typical post might say “at the Senate barber with the Boss and Ralph Nader” or “at CNN with the Boss who is about to go on SitRoom with wolf at 5:28 p.m.”

Also being talked about was Bardella’s enthusiasm for inserting himself into news articles. “He had a sick obsession with needing to see his name in lights,” says a veteran GOP press operative. With the exception of a few leadership positions, congressional press aides are expected to stay behind the scenes. “Members of Congress are trying to get their own names in the media mix and hire press aides to help them accomplish it,” says former House and Senate leadership spokesman Ron Bonjean, now a principal at Singer Bonjean Strategies. “That’s why it’s a golden rule that rank-and-file Hill press staff shall not be read, seen, nor heard in the media.”

Bardella rarely hesitated to go on the record with reporters. “Every day you pick up the paper and there is Bardella again,” says a former House GOP staffer. Bardella’s self-promotion increasingly triggered Capitol Hill chatter. In early 2010, Paula Nowakowski—beloved chief of staff to House minority leader John Boehner—died of an apparent heart attack at age 46. The tragedy hit hard in Republican circles. On the day of Nowakowski’s funeral, Politico ran a story suggesting that Nowakowski’s 24/7 Capitol Hill lifestyle may have contributed to her death. The story included a section on Bardella:

“ ‘I don’t ever stop,’ said Kurt Bardella, the prolific press secretary for Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.).

“Bardella sends out a daily stream of press releases, often getting up at 6 am and working until dark . . .” ‘There are times in any job when you have a crazy week, but on Capitol Hill it’s like that every day,’ he said. ‘For everyone who literally makes this job the centerpiece, it does take its toll.’ ”

GOP staffers weren’t happy. “It rubbed a lot of folks the wrong way that he would use that opportunity to remind everyone how hard he works,” says one Republican communications aide. “It came off as shameless yet not surprising at all.”

Bardella says he was quoted so often because Issa’s busy schedule made it impossible for the congressman to respond to every media inquiry himself, and the office believed it was better to engage the media than to ignore it.

Despite some eye-rolling from colleagues, Bardella’s career steamed ahead. His boss became the senior Republican on the Oversight Committee at just the right time. In the wake of the financial crisis, the federal government had put an unprecedented amount of taxpayer dollars at risk through bailouts and stimulus programs. Many of these initiatives—most notably the $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program—were unpopular on Main Street. And Democrats, who controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress, had less political incentive to rifle through these programs for abuse. The forces created an opening for Issa.

Issa’s team of 40 staffers dug into internal documents on the most controversial events: the federal bailout of AIG, Countrywide Financial’s program that extended discounted mortgages to members of Congress, and abuses at the community advocacy group ACORN, among others. Their findings provided a steady flow of news items—candid e-mails, damaging internal reports—that were sure to sizzle on the Internet. Bardella’s role was to identify the items of greatest significance and drop them into the news cycle at the angle most flattering to Issa.

Bardella leaked these items to reporters he knew didn’t have time to ensure they weren’t just printing spin. “You knew you were only getting a piece of the story, but if you didn’t write it, someone else would,” says a reporter who covered the committee. Journalists who passed on Bardella’s leaks risked being scooped by their competitors and dressed down by their editors. “You didn’t have a choice,” says a reporter who covered the committee. “You felt a little bit powerless.” Bardella’s strategy reflected “a recognition that the way the news cycle was evolving had created an artificial frenzy for new content,” Bardella says.

Even reporters who bristled at Bardella’s tactics acknowledge his results. “His skills and approach dovetailed perfectly with the Internet-driven political-media world,” says one.

By 2010, Issa was pitching himself as an anti-waste superhero in a land of big-government televangelists. The congressman bounced from one cable news show to the next, blasting the Obama administration’s handling of the $800-billion stimulus, the BP oil spill, and safety problems at Toyota. A February 2010 Bloomberg Businessweek headline called Issa “Tim Geithner’s Tormentor.” The New York Times anointed him “Obama’s Annoyer-in-Chief.”

“Bardella was walking around the greenroom like he was Ari Gold from Entourage—throwing his weight around as if we was a big deal.”

It’s tough to pinpoint how much credit Bardella deserves for his boss’s media makeover. “There’s no doubt Kurt’s tenacity and creativity were an asset to the chairman and helped make more people aware of his agenda,” says David Marin, a former Oversight Committee staff director. “But remember, we’re talking about a pretty dynamic, intelligent, and aggressive member of Congress. His profile was going to be raised regardless. Does one give Robin the credit for Batman?”

Still, Bardella’s status was rising even before he went to work for Issa. At the 2008 Republican National Convention in St. Paul, he bumped into George Stephanopoulos.

“Hey, Kurt,” Stephanopoulos said.

The two posed for a photograph that remains on Bardella’s wall today.

Bardella was invited to speak at George Washington University and became a regular at Republican hangouts on Capitol Hill. “I’ll go to Cap Lounge on Thursday night and people are like, ‘Oh, Kurt—what’s going on?’ ” he says.

Attending black-tie events with Issa, he hobnobbed with TV news celebrities. “We’re talking to [ABC News correspondent] Jake Tapper, we’re talking to [CNN’s] Wolf Blitzer,” he recalls.

Before a taping of Fox News Sunday, host Chris Wallace popped into the greenroom to greet Issa and his staff. “Is Kurt here?” Wallace asked.

The host led Bardella back to his office for some fact-checking assistance. “I think [Issa] was somewhat impressed at that point,” Bardella says.

In 2009, Politico named Bardella one of its 50 political professionals to watch. “Legislation takes time, it takes patience and it takes luck,” he told the publication. “Press is instant gratification.”

Many GOP press operatives cringed as Bardella’s ego inflated. One recalls running into Bardella and Issa before the taping of a cable news program. “Bardella was walking around the greenroom like he was Ari Gold from Entourage—throwing his weight around as if he was a big deal.”

In April 2010, Bardella read a New York Times Magazine article about Mike Allen, Politico’s tireless news machine. The story examined Allen’s must-read morning tip sheet—Playbook—while exploring the quirks that make him a unique Washingtonian.

Bardella had never read anything that so perfectly encapsulated the way Washington really works. He e-mailed the story’s author, Times reporter Mark Leibovich. “You should write a book about this,” Bardella wrote.

Regarded as one of the nation’s top political-profile writers, Leibovich is a rare figure himself. He’s a regular on political Washington’s cocktail circuit but still willing to skewer it. He can get close to prominent subjects while maintaining critical distance and—when appropriate—watch them choke on their own self-image. (See Leibovich’s 2008 profile of MSNBC’s Chris Matthews.)

The political hit piece is a classic Washington art form. “I befriend people, and I betray them publicly,” says one veteran Capitol Hill reporter. But when your objective is to protect a congressman’s reputation in the press, Mark Leibovich is about the last reporter you want to hear from.

As it happened, Leibovich’s article about Allen had led to a deal for a book on contemporary Washington culture. Leibovich thanked Bardella for his kind words.

That summer of 2010, Bardella worked with Leibovich on a front-page New York Times story about Issa’s efforts on the Oversight Committee. While the article helped entrench Issa’s political persona, its references to Bardella got staffers talking. At one point, Leibovich described Bardella as “Mr. Issa’s irrepressible spokesman and Mini-Me.”

Bardella had “almost a father/son relationship with Issa,” says one Republican press staffer. Democratic staffers on the committee had already been using “Mini-Me” to describe Bardella, joking that he dressed and even combed his hair like Issa, according to a reporter who covered the committee.

Bardella embraced the attention. On his Facebook page, he linked to a copy of the New York Times story, with the paragraphs about him moved to the top of the article.

Issa says his relationship with Bardella was “as close as I’ve been to any staffer.” Bardella says he considers Issa a father figure: “Darrell and I have talked about this recently. We’re both people who did it by our own playbook. We didn’t do it by how you’re supposed to do things. We forced our own way. And I definitely think he sees a little bit of himself in me.”

In November 2010, voters’ concerns about the sluggish economic recovery and government overreach propelled Republicans back into control of the House. The development would make Issa the Oversight Committee chairman starting in January. The power to subpoena the Obama administration further amplified his visibility.

Shortly after Election Day, Bardella and Leibovich got together. Leibovich was looking for characters for his book—lawmakers, journalists, staffers, and others who personified contemporary Washington. Although the two had previously discussed the possibility of Issa’s participation, Leibovich had a new idea: “I actually think you’re more interesting,” Bardella recalls Leibovich saying.

Bardella didn’t need much convincing. “I was flattered,” he says. “His fascination with me I found fascinating.”

Bardella says he saw the book as a chance to show Americans the guts of the political newsmaking process. “People wonder how the system works—and they should,” he says. He ran the idea past his superiors in Issa’s office and got their blessing.

In phone conversations and meetings in his Oversight Committee office, Bardella discussed with Leibovich his approach to generating press attention. Eventually he figured that instead of telling Leibovich about his job, he could show him. In November 2010, Bardella began forwarding to Leibovich e-mails he had received from other reporters without the knowledge of the senders.

Democratic staffers called him “Mini-Me,” joking that he dressed and even combed his hair like Issa.

At the same time, another reporter—Ryan Lizza of the New Yorker—was asking for face time with Issa. Lizza’s request sparked internal debate; some staffers insisted the liberal publication was unlikely to publish anything positive about a Republican known for shooting spitballs at Obama. But Bardella couldn’t resist. Bardella and some colleagues convinced his boss to participate in the story.

As Lizza reported his article, Bardella became entangled in a media dispute. In January, the Daily Beast’s Howard Kurtz posted a correction to a November story in which he mistakenly attributed some Bardella comments to Issa. Kurtz later claimed that Bardella had “impersonated the congressman.” Bardella denies this. He says he sent Kurtz an e-mail after their conversation to clarify that Kurtz had interviewed Bardella, not Issa.

Several days later, the Lizza piece landed. The decision to take part in the story had backfired: Rather than focusing on Issa’s Oversight Committee agenda as Bardella had hoped, Lizza walked the reader through Issa’s shadowy past: the gun charge, the auto-theft-related charges, the suspicion of arson.

For Beltway insiders, the passages attributed to Bardella were equally explosive. With Lizza’s audio recorder in sight, Bardella said the following:

“Some people in the press, I think, are just lazy as hell. There are times when I pitch a story and they do it word for word. That’s just embarrassing. . . .

“My goal is very simple. . . . I’m going to make Darrell Issa an actual political figure. I’m going to focus like a laser beam on the 500 people here who care about this crap, and that’s it. . . .”

In a follow-up story, Lizza quoted Bardella mocking reporters and news producers for “embarrassingly like begging to have Darrell on.”

Prominent placement in Mike Allen’s Playbook ensured that Bardella’s quotes appeared on every BlackBerry screen in political Washington. Republicans on Capitol Hill were livid. Bardella not only had facilitated the kneecapping of a prominent congressman, but he’d once again moved into the spotlight himself. House speaker Boehner’s office insisted Bardella be punished. Members of Issa’s staff called for his head.

But Issa’s office balanced Bardella’s mistakes against his previous efforts and decided to give him a second chance. “Darrell said we took it as a learning experience,” Bardella says. “I don’t think anyone who operates with the sheer volume of things we’ve had to deal with plays error-free baseball.”

Bardella says his comments were the result of fatigue, carelessness, and “vanity run amuck.” They do not reflect his true feelings about the media, he says. Shortly after the piece was published, Bardella contacted Lizza. “I just wanted to make sure you know that I don’t blame you for this,” Bardella said.

On Monday, February 28, Bardella posted an update on his Facebook page: “It’s the start of what I’m sure will be a memorable week.”

Bardella knew things were about to get complicated. The previous Friday, a source told Politico reporter Marin Cogan about rumors that Bardella had been forwarding reporter e-mails to Leibovich. The gossip had been circulating for some time. While Lizza was reporting his story, Bardella spoke freely about passing e-mails to Leibovich. Lizza was aware that his own e-mails with Bardella were being forwarded as well. He even joked with Leibovich about it, Lizza says.

Cogan mentioned the rumor to her colleague Jake Sherman, a spark-plug reporter who had written about Issa and the Oversight Committee. The reporters smelled a scoop and began working the story. (Full disclosure: My wife, Anne Schroeder, is a former Politico reporter.)

Shortly thereafter, Sherman called Bardella and demanded to know if he had been passing reporters’ e-mails to Leibovich without their consent. “Am I bcc-ing him on every e-mail I send out?” Bardella said. “Of course not.” Bardella refused to comment further on what he called “the details of my propriety conversations about [Leibovich’s] project.”

Unsatisfied with Bardella’s answers, Politico editor-in-chief John Harris on Sunday fired off a letter to Issa. “The practice of sharing reporter e-mails with another journalist on a clandestine basis would be egregiously unprofessional under any circumstances,” Harris wrote in his letter. Politico posted Sherman and Cogan’s story on Monday afternoon. By the next morning, news of Bardella’s e-mail sharing was everywhere.

After conducting an internal investigation, Issa concluded that although no sensitive committee documents had been exchanged, Bardella had indeed shared e-mails with Leibovich—a blatant breach of reporter/source trust. From November until late February, Bardella had sent Leibovich e-mails almost daily, more than 100 in all. E-mails from Politico reporters Mike Allen and Jake Sherman were among those shared, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Politico hammered away, posting seven articles on the subject over a 48-hour period. Harris says his publication’s coverage was not influenced by his umbrage at Bardella’s actions. “We do tend to get all over the story of the day,” he says. “When something happens, we swarm on it.”

The story spread to other news outlets—including the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. As the media circled, Bardella posted scripture on his Facebook page: “The LORD is my shepherd; there is nothing I lack.”

On Monday, February 28, Bardella posted an update on his Facebook page: “It’s the start of what I’m sure will be a memorable week.”

The content of the e-mails sent to Leibovich is the subject of tremendous speculation. Bardella insists they’re plain-vanilla media requests—cable news producers trying to book Issa, reporters asking about the Oversight Committee’s agenda—and contain nothing salacious or career-damaging. “All my e-mails with Kurt were the everyday exchanges you’d expect between a reporter and a press secretary,” Mike Allen says. Bardella says his goal was to show Americans what his job was really like, not to humiliate journalists. “I don’t believe [Bardella’s] motives were malicious,” Leibovich says.

But if the e-mails show this routine business to be at times obsequious or deceptive, they could undercut the credibility of the reporters who sent them. Leibovich’s book is expected to come out in 2013.

On the morning after Politico broke the story, Issa called Bardella to his office. “The question of whether he could stay or not was defined by the media, not committee,” Issa says. “He committed no offenses to the office I served in.” Still, Bardella’s actions had reflected badly on Issa, and everyone knew what had to be done. Bardella turned in his congressional ID and government BlackBerry.

He left the office and went directly to Union Station to buy a new cell phone. Driving to his apartment in Arlington, he called Issa’s office to make sure his former colleagues had his new number. As he passed in front of the Capitol, a cop pulled Bardella over for talking while driving and handed him a ticket.

Bardella hunkered down in his apartment for the next several days. Because he had surrendered his congressionally issued BlackBerry and e-mail address, reporters couldn’t find him. His grandmother learned of his firing on Hardball With Chris Matthews.

Bardella’s friends from Capitol Hill showed up at his apartment on the evening of his firing with Trivial Pursuit and wine, and they filled out his calendar with lunches and cocktails. Within a week, he was back on Capitol Hill, stopping by his old office, where he saw Issa. “You have to constantly make sure that you are not isolating yourself, because that is your first instinct,” says Bardella, adding that he’s not mad at Leibovich. He even did more interviews for the Leibovich book after he was fired.

On Capitol Hill, the Oversight Committee’s press team was adjusting to the loss. “Kurt is an example of somebody who is an essential part of the communications team,” Issa says. “He has been missed, there is no question about it.”

The first day in April—one month after his firing—Bardella stepped onto the basketball court at the Sports Club/LA in downtown DC. Afternoon hoops were a staple of his new routine.

Bardella arrived in an outfit inspired by his favorite athlete, LA Lakers star Kobe Bryant. He wore a Lakers T-shirt, knee-length Kobe Bryant shorts, Kobe Bryant high-tops, and black ankle socks with the NBA logo. Among the regulars, Bardella is known as “Kobe,” a nickname that refers to the one quality both men share. “[Bardella] never saw a shot he didn’t like,” says Sidney Jennings, who occasionally plays with Bardella.

The first time down the court, Bardella stopped at the three-point line and let one fly.

Swish!

The players on the sidelines exploded in laughter and cheers. “You gotta let ’em know, Kobe! You gotta let ’em know!”

After hitting a couple more shots, Bardella went cold. He missed three-pointer after three-pointer, often from several feet behind the three-point line.

Eventually, a teammate became frustrated. “Okay, new game plan,” the teammate said. “Let’s stop shooting threes. We’ve only hit one [three-point shot] in two games. Let’s get easy shots, lay-ups.”

“Well, for me a three is an easy shot, so I’m going to keep taking them,” Bardella said. After a swig of Gatorade, he stepped back onto the court. “I’m somebody that if you tell me not to shoot threes, I’m just going to shoot more.”

After he finished playing basketball, Bardella sat down in the sports club’s cafeteria. Issa was making news on Capitol Hill, and Bardella hated missing out. “It’s hard when you have that feeling that you could help these guys,” he said. “Instead, I’m playing basketball three hours a day.”

Bardella made clear that his devotion to his former boss remains absolute; he said he’d “take a bullet” for the congressman: “The hardest thing of all is realizing I failed Darrell Issa.” Bardella said he wouldn’t be surprised to find himself back in Issa’s office one day.

Asked if Bardella might work for him again, Issa says: “He always has a home with us.”

Bardella’s devotion to his former boss remains absolute. He says he would “take a bullet” for the congressman: “The hardest thing of all is realizing I failed Darrell Issa.”

Bardella still wanted to complete the final phase of his comeback plan: finding a good job. He said he had a buddy at the Daily Caller, a conservative Web site run by media entrepreneur Tucker Carlson. He could see himself fitting in there. Heck, he said, he could help make it the Huffington Post for conservatives.

Several days later, Bardella posted a Facebook message: “Wonder what this week will hold for me. . . .” The news soon broke: Bardella had been hired as communications director of the Daily Caller. At the suggestion of Bardella’s friend, Carlson had contacted Bardella and was impressed with his enthusiasm. “The guy’s an animal,” Carlson says.

Some Hill Republicans were stunned. “We thought he would be working for a nonprofit in Buffalo,” says a GOP press operative.

The new role brings Bardella back into contact with many in a GOP community that remains steamed. His participation in Leibovich’s book is seen as nakedly self-promotional. And the e-mail-sharing fiasco has forced Issa to dial back his attacks on the White House—which was supposed to have been a key part of the party’s congressional agenda. “Issa is doing what Kurt should have done—going underground,” says a GOP communications professional.

In recent weeks, Bardella has been trying to line up meetings with former colleagues on the Hill. Some are taking his calls; some aren’t. “If he learned how to just shut up for a while, if he would just lay low, he would get a second shot,” says a Republican press operative.

Meanwhile, Bardella’s off-screen efforts have gained traction. By convincing GOP presidential hopeful Tim Pawlenty to write a May 5 op-ed column attacking Obama’s health-care overhaul, Bardella got the Daily Caller’s name mentioned on ABCNews.com, FoxNews.com, MSNBC.com, and Politico.

But Bardella couldn’t resist the draw of the stage lights. On May 16, he wrote a column for the Daily Caller about Congresswoman Michele Bachmann. He blasted it to his media contacts, and it was picked up by ABCNews.com and MSNBC.com. He wrote another column on June 2.

On Capitol Hill, not many people were surprised to see Bardella advertising himself. “This could have been a wonderful learning experience,” says a GOP press aide. “But I don’t think he learned the right lessons.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly attributed a quote—“[Bardella’s press strategy reflected] a recognition that the way the news cycle was evolving had created an artificial frenzy for new content”—to a reporter who covered the Oversight Committee. In fact, this quote came from Bardella himself.

This article appears in the July 2011 issue of The Washingtonian. Follow the author of this story, Luke Mullins, on Twitter at @lmullinsdc.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)