Time weighs on John Wojnowski. It wears him down. It winds him

up.

Time, for Wojnowski, is not just the half century since the

priest in the mountains of Italy touched him. It is also the lost days

since then, the wasted months and years when he is sure he let everyone

down: his parents, his wife, his children, himself.

Markers of time are there, too, in the ragged datebooks that

cleave to his body like paper armor. While riding the bus late one night,

after another of his vigils outside the Vatican’s United States embassy,

he showed them to me: The 2010 datebook inhabits the right pocket of his

frayed chinos, 2011 the left; the 2012 book, its pages bound by rubber

bands, stiffens the pocket of his shirt.

He has come to this corner and stood with his signs for some

5,000 days. In his datebooks, he records—a word or two, just enough to jog

memory—the sights and sounds that keep one day from bleeding into the

next.

The Apostolic Nunciature, as the Vatican’s embassy is

officially known, sits across the street from the tumbling red digits of

the US Naval Observatory’s Master Clock, which displays official US time.

There’s a strange symmetry between that clock, its seconds yoked to the

oscillation of cesium atoms, and Wojnowski, whose own circuitry can at

times seem as unblinking and relentless.

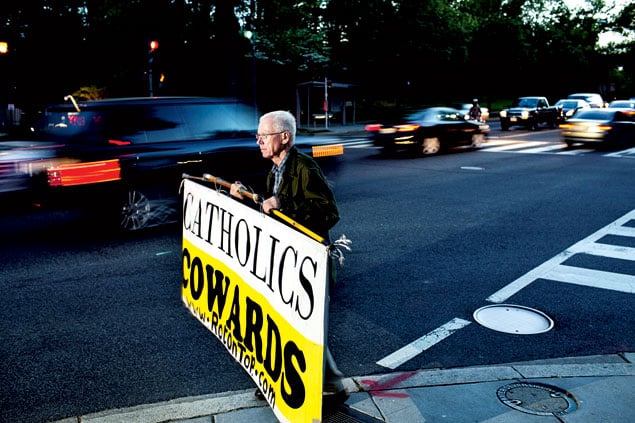

Almost every day for the past 14 years, Wojnowski has stood on

the sidewalk outside the nunciature with signs familiar to any

Washingtonian traveling on Massachusetts Avenue in Northwest DC: MY LIFE

WAS RUINED BY A CATHOLIC PEDOPHILE PRIEST or CATHOLICS COWARDS or VATICAN

HIDES PEDOPHILES. He carries his signs, like some cross, for hours. He

pivots when the stoplight changes, to face the onrush. He walks up to the

windows of tour buses so passengers can see.

For Wojnowski, every second of sign-bearing is precious. On the

subway on his way to the nunciature, he used to change cars at each

station so the greatest number of riders could see his message. On a bus

ride up Massachusetts Avenue one afternoon, he scolded me for standing

close to him as we prepared to exit. “Don’t hide my sign,” he

said.

After 14 years, I asked, did every second still count? Hadn’t

he earned a day of rest? “It’s inconceivable,” he said. “There are not

breaks in a war.”

When his daughter and her family visited Washington a few years

ago, he cut short visits to the National Zoo and the World War II Memorial

so he could be at the corner at his usual hour. “He went right to

Massachusetts Avenue for the rest of the day,” says his daughter, Kasia

Bonner, a stay-at-home mother who lives in Southern California. “He went

to ‘work.’ That’s what we call it.

“It’s his everything,” she says.

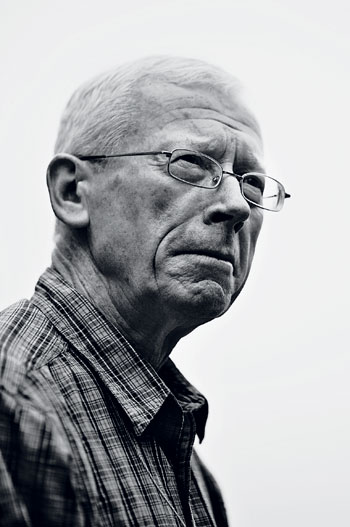

Wojnowski turned 69 this year. He was for most of his life an

ironworker. He wore a hard hat, toted a lunch pail, teetered on steel

beams high above the ground. He built bridges and nuclear power plants and

Smithsonian museums. But his toughness isn’t visible on the outside. He

stands 5½ feet tall, with an expressive face and fine white hair that

retains glimmers of its original red. His skin is so sensitive that it

turns an almost translucent crimson in the sun. Wire-rimmed glasses rest

low on his nose.

For a man with an eighth-grade education, his vocabulary is

surprisingly broad and precise. His voice, a gruff staccato forged of a

Polish-Italian upbringing, is often silenced by a stutter.

Two summers ago, on a hot walk home from his evening vigil, he

was stricken by a heart attack. Two weeks later, he was back on the corner

with his signs.

I met him outside the nunciature one February rush hour after

dark, when temperatures had slipped into the 20s. Gusts whipped down

Embassy Row, and after a few minutes I had trouble feeling my fingers.

When my pen froze, Wojnowski handed me the mechanical pencil he uses to

make inscriptions in his datebooks. He had been out for more than two

hours, and his nose was dripping. “I hate the cold,” he said.

Wojnowski sees himself as a David: a righteous nobody at war

with a colossus. He described himself to me variously as a cripple, a

failure, a weakling, a naif. The forces in league against him, by

contrast, were malevolent, arrogant, cowardly, parasitic.

“I’m a poor, ignorant peasant fighting this global

institution,” he says. “If a person has a drop of honor, he cannot give

up.”

But 14 years is a long time. It is long enough for daughters to

marry, grandchildren to be born, hearts to grow old and falter. It’s long

enough for the weights tied to the bottom of his banner to have etched

ruts in the sidewalk’s concrete. It’s long enough to ask, as his children

have, whether it’s time for a new strategy. Or time, even, to

stop.

Yet beneath their concern for their father is a still

unanswered question: Without justice, how is a wronged man—a wounded

man—to heal?

John Wojnowski occupies an unusual place in the movement to

hold the Roman Catholic Church accountable for sexual abuse of children by

clergy. The issue came into public view in the United States in 1985 when

a Louisiana priest who had been accused of molesting hundreds of children

pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two decades in prison. It burst into

full-blown scandal in 2002 when the Boston Globe published a

series of articles about a former Massachusetts priest named John J.

Geoghan. More than 130 people had accused Geoghan of fondling and raping

them as children over Geoghan’s 34 years in the priesthood. To keep the

allegations from coming to light, the archbishop of Boston, Cardinal

Bernard Law, shuffled Geoghan from parish to parish without disclosing his

history—a practice soon revealed as commonplace in dioceses across the

United States.

“For decades, within the US Catholic Church, sexual misbehavior

by priests was shrouded in secrecy—at every level,” the Globe

reported. “Parents who learned of the abuse, often wracked by shame,

guilt, and denial, tried to forget what the church had done. The few who

complained were invariably urged to keep silent.”

A study commissioned by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops

discovered that from 1950 to 2002 some 4,392 priests in the United States

had faced allegations of sexually abusing about 12,500 minors, most of

them boys. The accused represent about 4 percent of all Catholic priests

in ministry over that period.

As the scope of the scandal grew, so did the money paid out to

victims. According to an annual survey conducted by Georgetown University,

from 2004 to 2010 American dioceses paid $1.6 billion to victims to settle

sexual-abuse claims. The Archdiocese of Washington and its insurers paid

nearly $1.9 million, including a $1.3-million settlement in 2006 with 16

men molested by priests between 1962 and 1982.

The scandal also fanned the growth of advocacy and support

groups, such as the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP)

and Voice of the Faithful, and superlawyers who built a cottage industry

representing abuse victims.

But in this set piece of American accusers, abusers, and

advocates, Wojnowski remains an outlier. His alleged abuse took place in a

small village overseas. He hasn’t sought the help of victims’ groups. And

in his quest for reparations, he hasn’t filed a lawsuit, hired an

attorney, or sent a claim to the Italian diocese in which he says a priest

molested him.

His battle plan remains one of dogged, solitary public protest.

A few Catholics I spoke to said they saw his sign-bearing as part of the

Christian tradition of “witnessing.”

Wojnowski told me he chose the Apostolic Nunciature as his

target not just because of its visibility—an average of 33,000 cars pass

that stretch of Massachusetts Avenue each weekday—but also because he

holds the pope personally culpable for the Church’s failure to make him

whole.

“The question is for Rome,” Wojnowski says.

When I called David Clohessy, director of SNAP, he said

Wojnowski remains a singular figure in the survivors’ movement. The

closest parallels aren’t particularly close. In the early 1990s, a man in

Orlando walked up the aisle at church services, handing out flyers

accusing a priest there of molesting him as a boy. In 2003, a police

officer in Oxnard, California, who claimed he’d been molested multiple

times as an altar boy, spent Holy Week in a round-the-clock fast and vigil

outside a Los Angeles cathedral.

Though Wojnowski keeps his distance from other survivors, many

know him, if not by name, then as the man with the signs outside the

Vatican Embassy. Last year, Wojnowski wandered unannounced into SNAP’s

annual conference, at a hotel in Crystal City. When people in the audience

recognized him, Clohessy says, they gave him a roaring standing

ovation.

“I remember just crying when I shook his hand,” Clohessy says,

his voice catching. “It’s got to have been an incredibly long, lonely,

hard, hard road for him. It’s emotional now just talking about it. So many

victims are so completely trapped in shame and silence and confusion and

self-blame, and I think they wish they had the fortitude to do something

like that.”

Just as notable, Clohessy says, was Wojnowski’s going public

four years before the issue drew widespread notice: “He’s made more people

think about child abuse than all but probably a handful of people

anywhere. Oprah Winfrey has made more people think about child abuse than

John. But he’s in rarefied company.”

Clohessy likes to think Wojnowski has an influence on the

Vatican officials who live and work in the nunciature. “I suspect that

every single day, given the magnitude of this crisis, someone in that

office is making some decision relative to abuse and cover-up, deciding

whether and how to respond to the bishop who asks for their guidance on

whether this perp should be moved or demoted or defrocked. Within hours or

sometimes probably minutes of making that decision, they’ve seen John.

That can only, only help.”

Bill Casey, an Alexandria man who has served on the national

board of Voice of the Faithful, says Wojnowski’s form of protest “wouldn’t

be the first choice for most people because it’s too hard.

“There are many victims who use other means,” Casey says.

“They’ll have press conferences, they’ll do vigils, they’ll pass out

leaflets when a known predator is living in a community. But I don’t know

of any other single individual who has stood witness for such a long

period of time.”

Precisely what the Apostolic Nunciature thinks of Wojnowski is

unclear. The current nuncio, or Vatican ambassador, is Archbishop Carlo

Maria Viganò, a Northern Italian priest and former deputy governor of

Vatican City who was reportedly pushed out of Rome because of his

criticism of corruption and cronyism in the awarding of Vatican contracts.

(His critiques became public this year after his letters to the pope were

leaked to the Italian press in a scandal known as “Vatileaks.”) Viganò,

who became nuncio to the United States last October, didn’t respond to

phone calls, e-mails, faxes, and a certified letter requesting an

interview for this story.

The Archdiocese of Washington, to which Wojnowski has appealed

for compensation, issued a written statement to The Washingtonian

saying it acted as soon as Wojnowski reported the allegations in a 1997

letter.

“The Archdiocese of Washington immediately contacted the

diocese in Italy where the abuse allegedly occurred and which would be

responsible for that priest’s conduct in an effort to find out what

happened,” Chieko Noguchi, the archdiocese’s spokesperson, wrote. “It was

found that the priest allegedly involved passed away many years ago. This

information was provided to Mr. Wojnowski and he was encouraged to contact

the diocese in Italy to pursue his claim of abuse. Additionally, the

Archdiocese of Washington, in our concern for Mr. Wojnowski’s situation,

offered him free counseling and therapy, which he has declined to

accept.”

I went to meet Wojnowski for the first time on a cold, rainy

afternoon. I arrived outside the nunciature early and took cover across

the street under a bus shelter near the gate of the US Naval

Observatory.

At 4:40, I noticed a slight man with khaki pants and heavy

black shoes ambling toward me. A plaid scarf was held around his neck by

an oversize safety pin. Slung over his shoulder was a salmon-colored sack

with sorrypope.com written in black marker along its length. A loop of

string around his neck traveled first to a cell phone in his shirt pocket,

then to an old Casio wristwatch, its straps lopped off, that dangled at

his waist. There was an air about him of an old-world train

conductor.

I had no sooner asked whether he was Mr. Wojnowski than I

realized I didn’t have to: On a patch above the right pocket of his

olive-green military jacket—a relic from his Army days, I later

learned—was wojnowski stitched in block letters.

To get to the nunciature, he takes two buses and the Metro from

his home in Bladensburg. It’s a journey of 60 to 90 minutes each way. He

exits the bus one stop early because there’s a wooded area across from the

British Embassy where he can relieve himself. There are no public

restrooms near the nunciature, and holding it in is one of his vigil’s

many physical ordeals.

As rain pecked the shelter roof, he pulled from the sack a

mismatched set of dowels and began lashing them end to end with plastic

cinch ties and duct tape to form the rod from which his banners drape. He

buys most of his gear from a dollar store near his home. “This is a mop

handle, and this is a piece from a broom or something,” he said. “It’s a

low-budget operation.”

He used to make his signs himself in his back yard, stenciling

plywood or decorating fluorescent poster board with peel-off letters.

Lately, he has been mail-ordering professional-looking eight-by-three-foot

banners from a company in California. Since 1998, his signs have borne at

least 68 messages, from the straightforward (catholic clergy molest boys

worldwide) to the cryptic (rotontop.com) and occasionally scatological

(watch catholic church stomping in her very own excrement).

The Apostolic Nunciature is a boxy three-story building of

beige stone with a Mediterranean tile roof at the corner of Massachusetts

Avenue and 34th Street. The Vatican flag, imprinted with the papal tiara

and the crossed keys of St. Peter, hangs over an otherwise unmarked front

door.

When I proposed a minor shortcut from the bus shelter,

Wojnowski fretted about the absence of crosswalks. “Let’s keep it legal,”

he said.

When the crosswalk signal finally flashed, we crossed the

street and Wojnowski strode onto the nunciature’s front lawn. He unfurled

his catholics cowards banner across the wet grass, slid the dowels through

a set of rope loops, and, with a fluid sweep of his right hand, hefted the

banner.

“Not in a million years,” he said, “did I think I’d do

something like this.”

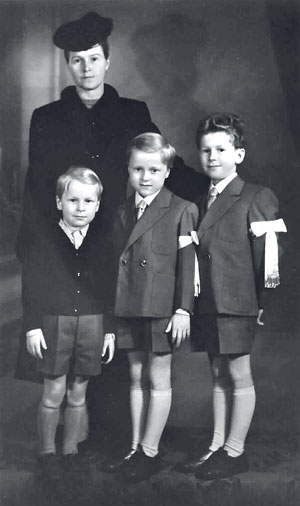

John Wojnowski, the eldest of three brothers, was born into a

Catholic family in Warsaw in the midst of the April 1943 ghetto

uprising.

The Nazis would murder at least 5 million Poles—3 million of

them Jews and many of the others Catholic. A few months after his birth,

Wojnowski’s mother, Cecylia, fled with him to her hometown, Czarnków, a

small city some 250 miles west of Warsaw.

As a young man, Wojnowski’s father, Jan, had entered a seminary

run by the Marian Fathers, a Catholic order. The Marians sent him to the

Pontifical Gregorian University, an elite institution in Rome, where he

got a PhD in philosophy but aborted his clerical training, deciding the

priesthood wasn’t for him.

Back in Poland, he began working toward a second PhD, in

sociology, but after the war the country’s leaders sent him to Italy,

first as consul to Naples, then, in 1947, as consul general to Milan,

where his family joined him.

Like other Polish diplomats of the era, Jan Wojnowski grew

disenchanted with the new Communist government back home. In October 1948,

Time magazine mentioned him in an article headlined displaced

diplomats.

“A studious, courteous, bespectacled book collector, he had

never been very happy in his consulate,” the article read. “Last summer,

after a trip home, he cut out meat, ate only tea and toast for supper, and

gave up buying books. Staffers wondered why he was saving his pennies.

Last week they found out. Two days after his replacement arrived from

Warsaw, the ex-consul bade them all farewell and proudly displayed two

tickets for home, via Venice. Boarding the train next day, he bundled his

family off before it reached Venice, roared across the Swiss border in a

taxi, and hopped the first plane to Johannesburg, South

Africa.”

John Wojnowski told me there was no Swiss border crossing and

no flight to South Africa. Instead, the family hid out for a few months in

two small Italian towns, Rapallo and Bottanuco, before resurfacing in

Milan. “In Italy, after my father’s defection, we had to stop speaking

Polish,” Wojnowski says. “We were told to tell people we were Danish.” In

the phone book, the family was listed under a false last name,

Saner.

Jan Wojnowski eventually landed a job as chief library

cataloger at the Catholic University of Sacred Heart in Milan, the largest

Catholic university in Europe. John, his eldest, was a gentle, intelligent

boy with a fondness for photography—he bought the family’s first camera, a

Kodak box camera, and snapped artfully composed photos at scenic spots

around Milan. By all accounts, he was the sharpest of the brothers, often

at the top of his class, with a knack for quickly sizing up situations

that left other children baffled.

But the brothers had a rebellious streak—skipping school to

play hockey in the park, among other shenanigans—and their parents sent

them to a Catholic boarding school near Venice that doubled as an

orphanage.

John, then in fourth grade, remembers his time there as trying.

The communal bedroom was so poorly insulated that icicles formed indoors

in winter. Breakfast—coffee-flavored milk in a sometimes moldy bread

bowl—was often so stomach-churning that students sneaked into the staff

dining room to fight over the priests’ leftovers.

According to Wojnowski, discipline was cruel. One priest forced

John and his classmates to face the crucifix as he kicked them in the

buttocks with the point of his shoe. Another priest gave delinquents a few

seemingly loving caresses on the cheek before administering a sharp slap.

Wojnowski still remembers a classmate, one Palmieri, who mustered the

courage to stand up to the clergyman.

“Now you’re big and strong,” he recalls Palmieri telling the

priest. “But when you will be old and in a wheelchair, I will come with a

knife and I will kill you.”

Like most Catholic boys of his generation, Wojnowski had been

raised to place absolute trust in priests. Palmieri’s boldness made an

impression.

Wojnowski returned to Milan for sixth grade but was sent the

next year to another Catholic orphanage and boarding school, near Torino.

It was there that he met a classmate who would invite him to a place

called Cuzzago.

A village of a few hundred souls some 65 miles northwest of

Milan, Cuzzago sits off a local highway in Italy’s picturesque Piedmont

region. To the north rise snow-capped Alps and the border with

Switzerland; to the east unfurls Lake Maggiore, the glittering pleasure

ground popularized in Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms.

The friend from boarding school had once stayed with

Wojnowski’s family in Milan. He returned the favor by inviting Wojnowski

and his younger brothers to spend part of the summer of 1958 with his

family in Cuzzago. The brothers—John, 15; Mikolaj, 13 or 14; and Eugene,

12—bought an army-surplus tent, caught a train from Milan, and set up camp

in their friend’s front yard. (In 1971, Eugene died, in his twenties, in a

car accident in Italy.)

The visit began idyllically. The boys hiked into the mountains,

picked berries, and played in trenches dug during the First World

War.

One day, a somewhat overweight priest about their parents’ age

approached John and Mikolaj in town. John had recalled seeing him once

before, walking silently in a nearby orchard with his breviary, a book of

Catholic liturgy. Now the priest asked them questions. When John mentioned

his struggles with Latin, the cleric invited him to the rectory for what

he said would be private lessons.

“He told me, ‘Come and I’ll tutor you.’ ”

John went soon after—perhaps the next day—with Mikolaj in tow.

According to both brothers, the priest, in a traditional black cassock,

sat Mikolaj in a separate room, gave him a book to read, and shut the

door. He then led John to a room with a window and told him to take a

seat. The priest drew up a chair beside him.

Victims of sexual abuse “tell you that molestation begins with

showing pictures or giving alcohol,” Wojnowski says. “There was nothing

like that. He was very direct. He sat next to me. The first thing he did

was put his hand on my knee—I had short pants—and right away he reached

and grabbed me.”

The priest shoved his hand up Wojnowski’s shorts, touched his

penis, and told him to masturbate.

“In the Catholic faith, masturbation is a mortal sin,”

Wojnowski says. It was the only sin for which he’d ever gone to

confession. “Suddenly a priest was telling me to do it.”

Instead of complying, Wojnowski challenged the priest. “I must

have been stalling,” he remembers. “I said, ‘Show me your thing, your

peter.’ ”

Wojnowski was startled by the priest’s response. “I have this

terrible problem,” the priest replied. The implication, as Wojnowski, then

a terrified boy, understood it, was that some accident had cost the priest

his genitalia.

Wojnowski has no recollection of what happened next—or whether

anything did. His next memory is of being outside the rectory in a state

of dread. “You cannot understand the feeling,” he says. “The sense that it

ruined my life forever. The feeling was so dark, so visceral, so profound:

For what? For nothing, I ruined my life.”

I asked if the horror was connected to a fear of hell. It

wasn’t, he told me. It came from a feeling common to children abused by

trusted authority figures: self-blame. “Like I did it,” he says. “I felt

responsible.”

He never returned to the rectory. He never knew the priest’s

name.

What Wojnowski wouldn’t learn until many years later—because no

one talked about it for the next four decades—was that his brother had

witnessed the alleged abuse. Mikolaj had a question about a passage in the

priest’s book and had gotten up to find him.

“When I walked in, the priest had his hands on my brother’s

privates,” Mikolaj, a retired economist for the National Marine Fisheries

Service who lives on Martha’s Vineyard, told me. “When I saw that, I went

out. We never discussed it after.”

John Wojnowski says he immediately repressed the memories of

his encounter with the priest. His life, though, entered a downward

spiral. His parents and an uncle from Washington visited the boys in

Cuzzago a few days later, and his father sensed something

amiss.

“What’s bothering you?” he asked.

John told his father that he had visions of the mountains

around them crumbling.

Back in Milan that fall, he sneaked sips from his parents’

vodka. He ran away from home, riding a bus to a nearby town before the

police recovered him. He started skipping church and never again went to

confession. When classmates in the eighth grade asked why he always seemed

so sad, he lied and said a friend had died.

His father took him to a psychologist at the university, who

ran tests but made no diagnosis. “I was told I was very intelligent, but

nothing came out of it,” Wojnowski says.

Once a star student, he flunked out of eighth grade and signed

up for an auto-mechanic program at a Milan trade school. It didn’t offer

the escape he was looking for, and he quit after two years—after receiving

a letter from an organization offering to resettle refugees in other

countries.

He boarded a ship for Canada and reported to Morden, a small

town in southern Manitoba, where he spent the summer working at a gas

station. In search of better prospects, he took a series of menial jobs:

laborer at a Winnipeg sheet-metal factory, rail worker for Canadian

Pacific, dishwasher at a Toronto country club.

Back in Italy, Mikolaj grew worried about his older brother. He

applied under both their names for immigration visas to the United States.

The pair reunited in 1963 in New York and traveled together to Washington,

where their uncle Hubert worked for the federal government.

The brothers enlisted in the US Army, Mikolaj in the infantry

and John, who tested better, in a school that trained soldiers to repair

the hydraulics of tanks’ artillery turrets. John was later deployed to

Germany to maintain army trucks. He was a good enough shot that he made a

brigade-wide pistol team, competing in the 7th Army Small Arms

Championship.

After their three-year hitches, Mikolaj enrolled at the

University of Maryland on the GI Bill and worked toward an economics

degree. John moved into his brother’s Hyattsville apartment and

languished. “He had no ambition whatsoever,” Mikolaj says. John had no

friends, either, and scarcely left the apartment.

Mikolaj drew his brother’s attention one day to a notice from

Ironworkers Local 5, whose jurisdiction covered much of the capital

region: It was looking for apprentices. John joined the union in 1967, the

year he became an American citizen. He had shared his father’s first name,

Jan, but changed it now to John.

The next year, when he was 25, he returned to Czarnków, Poland,

for a family visit. There he met a 19-year-old named Barbara, a “naive,

simple, gentle” woman, he says, the daughter of a blacksmith who had

rented rooms from one of Wojnowski’s aunts. On a walk together down a

hillside, he reached out to squeeze her hand. He had never had a

girlfriend, and he describes his attraction as equal parts impulsive and

desperate. He married her in a Catholic church two days before his

monthlong stay was up. The next year, she joined him in an apartment he’d

found in Mount Rainier in Prince George’s County.

A girl, Kasia, was born in 1971 and a boy, John Max, four years

later. But Wojnowski remained reclusive, given to solitary pursuits that

kept him at a chilly remove from family life.

For John Max, a federal police officer and Marine, a memory

that still rankles is his father’s inaction after they bought a back-yard

basketball hoop that required assembly. “He always promised me he’d put

that basketball court up and build a pole and cement it in the ground, but

it never got accomplished,” he said. “It was one of many things he

promised to do but never accomplished. It kind of hurt because I was

always wanting to have that person to throw that ball in the back yard

with.”

Instead, his father holed up with power tools in his basement

workshop, which the children were forbidden to enter. “When I compare him

to other fathers, it was like he was almost nonexistent,” John Max

says.

Besides his brother Mikolaj and one ironworker friend,

Wojnowski spent little time with other people.

One of John Max’s rare warm memories of his father is the day

they drove past the National Air and Space Museum, John Max’s favorite,

and his father mentioned that he’d helped build it. Such moments of filial

pride were despairingly few.

When she was 16, in an act she describes as “typical

rebellion,” Kasia moved in with a friend’s family and stayed there through

high-school graduation.

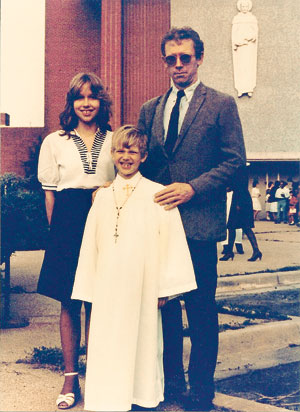

The children received their First Communion at St. Bernard

Parish in Riverdale. On Sundays while Barbara and the kids were in church,

John sat outside in the family’s Chevy van with a newspaper. “I asked Mom,

‘Why isn’t he coming in?’ ” John Max says. “She’d make up some excuse:

‘Oh, he’s tired.’ ”

It was one of the many aspects of their father’s behavior that

wouldn’t make sense until years later.

In 1978, when he was first made an assistant pastor, a priest

in Texas named Rudolph “Rudy” Kos began inviting boys to spend the night

with him in the rectory. He started with foot massages and advanced to

oral and anal sex, assaulting as many as 50 boys over the next decade.

Despite complaints from parishioners, other priests, and a pastor, the

Diocese of Dallas made Kos pastor in 1988.

In July 1997, jurors in a Texas civil trial found the Dallas

diocese responsible for gross negligence and awarded 11 plaintiffs $119.6

million in damages, then a record judgment for a clergy abuse case. The

amount was later reduced to $31 million; Kos was sentenced in 1998 to life

in prison.

When Wojnowski read about the award in the Kos case, memories

of his own abuse four decades earlier bubbled to the surface.

“I actually thought, ‘Lucky me—I could use $20,000,’ ”

Wojnowski says. “It’s embarrassing, but that’s what I thought. The mention

of money was incentive to think about it.”

A year or two earlier, he and Barbara had separated. Wojnowski

still speaks with her by phone several times a week, but he told me

Barbara didn’t want to be interviewed. She lives in Florida, and efforts

to reach her independently were unsuccessful.

In early August 1997, a week or so after reading about Kos,

Wojnowski drove to St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Landover Hills. He chose

the church because it was an anonymous-looking building across from a

strip mall, a place where he wouldn’t be recognized. He parked far away in

the mall lot, then walked over.

A priest, Father Michael Blackwell, invited him into his office

and offered him a seat. Tormented by old memories, Wojnowski couldn’t

bring himself to sit. He struggled to form words. “I don’t know how long

it took me before I was able to say, ‘I was molested by a Catholic

priest.’ ”

Blackwell referred him to a therapy program run by Catholic

Charities. Still anxious about his privacy, Wojnowski made an appointment

from a pay phone in the New Carrollton public library.

He went to the therapist just three or four times—long enough,

he says, to see the source of all of his misfortunes. His transformation

from a happy child to a sullen loner, his sudden failure in school, his

emotional insecurity, his stunted career, his broken marriage, his

distrust of and alienation from other people, his stutter—he came to

understand them all as symptoms of that day in Cuzzago.

“This thing completely changed my personality, my life,

completely destroyed it,” he says. “I put everything

together.”

It is, of course, impossible to know how Wojnowski’s life might

have differed had he and the priest never met. But when he thinks about

his father, a diplomat, and his brother, a government economist, he sees

his alter egos—the men he might have been.

In late August 1997, with the help of Father Blackwell,

Wojnowski wrote to Cardinal James Hickey, then archbishop of Washington. A

Midwesterner who had previously been bishop of Cleveland, Hickey was one

of the first American bishops to take seriously the problem of clergy

sexual misconduct. As early as the 1980s, he put in place policies in

Washington to educate priests and identify potential abusers.

Wojnowski had signed a form permitting his therapist at

Catholic Charities to release details of his case to the Archdiocese of

Washington “for the purposes of obtaining compensation for pain and

suffering related to being sexually abused by a priest.”

In his letter to Hickey, however, Wojnowski asked only for an

investigation. “In the first ten years, I never asked for a specific

amount,” he says. “I just always expected the Church to make a judgment

about how much worth there was to a wasted life.”

A month later, Hickey’s vicar general, or second-in-command,

auxiliary bishop William Lori, wrote asking for more details. Wojnowski

replied with a fuller story—and exasperation.

“Please forgive my impatience but is it not against the spirit

of Christian Charity, or even against basic human decency, to try to delay

justice to a person who already suffered for 39 years?” he wrote. “I will

not wait 300 years like Galileo or 137 years as Darwin.

“A rapid and amicable settlement will restore my confidence and

provide security to my remaining years,” he wrote. Then, hinting at the

protest to come, he added, “It will also prevent an unnecessary and

unpleasant public confrontation that could have unforeseen

consequences.”

The letter concluded with the phrase “GOD BLESS

AMERICA!”

Months passed with no reply. Wojnowski wrote Lori more letters,

including one, in January 1998, suggesting that the delays were perhaps “a

problem of severely myopic, pathologic institutional avarice.”

“I must sincerely thank-you for prolonging this confrontation,”

Wojnowski wrote. “I believe it was excellent therapy after my 39 years of

insecurity. I believe that it is possible to gauge my progress by the tone

of my letters. Further therapy will make me positively fierce. I am still

only seeking a fair, non punitive compensation.”

Faced with more silence, Wojnowski photographed a question mark

at the end of one of his letters to Lori, enlarged it to a height of four

feet and traced its outline on a plank of plywood. At the top of the

plank, he wrote, “Bishop Lori, do you recognize this question

mark?”

He drove into DC and stood with it on the sidewalk outside the

nunciature: It was his first sign.

Within days, he says, Lori replied to his letters. “He wrote,

‘Unfortunately, that priest who allegedly molested you died. But I will

pray for you and the church will pay for your therapy.’ ” (When I asked to

see the letter, Wojnowski searched for it but couldn’t find it. The

Archdiocese of Washington declined to release the letter but confirmed its

broad outlines.)

Thus began Wojnowski’s 14-year odyssey on the corner of

Massachusetts Avenue and 34th Street. He took early retirement from the

ironworkers’ union—he was 55—and gave himself over to the next phase of

his life.

“After I received that letter from the bishop,” he says, “I had

no choice.”

Bishop Lori, who left Washington in 2001 to become the bishop

of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and was this past March named archbishop of

Baltimore, declined to be interviewed. A spokesman for the Bridgeport

diocese, Brian D. Wallace, said, in written replies to questions, that

Lori did everything in his power to help Wojnowski, even though the

alleged molestation happened on foreign soil and the American Church had

no legal liability.

“Bishop Lori immediately contacted the Bishop in Italy,”

Wallace wrote. “While it did take some time to get the response from Rome,

he learned that the priest had passed away and that he had an unblemished

record with no previous allegations. The 40 years in between the abuse and

the disclosure precluded a reliable and fair investigation.”

Though the allegations “couldn’t be prov-en or disproven,”

Wallace wrote, “clearly Mr. Wojnowski is aggrieved [and] we in no way seek

to discredit or belittle in any way, suffering that Mr. Wojnowski may have

experienced.”

Wojnowski lives on $2,200 a month from Social Security and his

ironworkers’ pension. At the time of that first exchange of letters with

Lori, he says, he would have settled—and abandoned his daily protest—for

$240,000. Today he wants in the neighborhood of $5 million, as recompense

for the “insult” of the Church’s having ignored him for so long. Experts

told me that would be among the highest individual settlements in a clergy

abuse case—and of an order impossible to attain without a

lawyer.

Father Thomas Doyle was pushed out as canon lawyer for the

nunciature in 1986 after coauthoring an internal report warning US bishops

of the looming sexual-abuse crisis. He has since become a leading

consultant for plaintiffs’ lawyers seeking damages in clergy abuse cases.

When I reached him by phone at his home in Northern Virginia, he told me

he has met and admires Wojnowski. But he offered a blunt assessment of

Wojnowski’s methods: “The only way anybody who has been sexually abused

has received any justice at all—any justice—has been in the court, or with

a civil attorney.

“The fact is they ignore him because they can ignore

him.”

Attorneys occasionally approach Wojnowski on the corner and

offer their services pro bono, but he turns them away. His distrust of

strangers is such that he says he can’t be sure they aren’t agents of the

Church.

And so his daily confrontation has become a kind of end in

itself. It’s more cathartic, he says, than any counseling the Church might

offer.

“On that corner, I started talking to people—it’s how I started

to talk,” he says. “Now I feel like a motor mouth,” he adds, laughing. “I

tell everybody what happened. I told so many people what happened. What

better therapy is there?”

Father Blackwell, the first person Wojnowski told about his

alleged abuse, had been at St. Mary’s four years when Wojnowski stepped

through the door.

I reached Blackwell at the Church of the Resurrection in

Burtonsville, whose rectory he has lived in since retiring in 2007. He

told me Wojnowski was so distraught when they met that he worried about

his mental stability. Blackwell found him educated and articulate and

never formed a firm opinion about his credibility. All the same, he said,

“you wonder if this is delusional, paranoid, and all that kind of thing,

which is why I suggested to contact Catholic Charities.”

Not long after Wojnowski began picketing the nunciature,

Blackwell says, he got a call from Bishop Lori—the only time in his career

anyone so high up the Church hierarchy has called him about anything. Lori

wanted to confirm that Blackwell had met with Wojnowski, then asked

whether Blackwell had recommended that Wojnowski take his protest to the

streets.

“Lori asked if I had suggested to John to do this,” says

Blackwell, who is 79. “I said, ‘Well, I used to drink a bit, but I’m not

insane.’ ”

When I asked Lori’s spokesman, Brian Wallace, about Blackwell’s

account, he said it was “unlikely” that Lori “would have asked a priest if

he had put the victim up to his protest. Such behavior is totally

inconsistent” with what Wallace said was Lori’s “transparency” in dealing

swiftly and openly with earlier abuse cases in the Archdiocese of

Washington.

Even a single instance of child sexual abuse, particularly by a

parent or other authority figure, can cause long-lasting damage. Adults

who were victimized as children have higher rates of substance abuse,

suicidal behavior, depression, family dysfunction, and posttraumatic

stress disorder. Many victims suffer from low self-esteem and feelings of

guilt and powerlessness, and some lose the ability to trust other

people.

When I was with Wojnowski outside the Dupont Circle Metro one

day, he rejected a friendly cabbie’s offer of a free ride to the

nunciature. He refuses food from strangers, for fear of being poisoned,

and declined my offer to interview him over coffee or a meal. In our

interviews, he was affable, considerate, and generous with time and

information. But when I asked tougher questions, he displayed flashes of

suspicion that bordered on paranoia.

“I begin to wonder if you are working for the Church,” he said

one day, long after I had told him I was Jewish.

David Clohessy, of SNAP, told me that “most victims cope with

childhood abuse in self-destructive ways. Many have criminal records and

addiction issues—four divorces and five DUIs. When victims think about

stepping forward, oftentimes one of their first concerns is ‘People will

attack me.’ Then there’s family considerations. I can’t tell you how many

victims have said, ‘I’d love to take action somehow, but it would kill my

mother, who is a devout believer and still in the same parish.’

”

And yet for adults who do take action, especially if it fails

to produce results, there’s a risk of a kind of paralysis. “For some, they

are turning something very negative in their lives into something

productive and potentially helpful,” says Esther Deblinger, professor of

psychiatry at the University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey,

who codirects a treatment center for abused children. “For others, maybe

it’s not so healthy. Maybe it’s causing them to get stuck on one very

painful time in their life.”

When Wojnowski told members of his family about the abuse, they

felt as though a veil had been lifted. Behavior that had perplexed and

saddened them seemed now to have some justification. Despite Wojnowski’s

worries, even his mother, who remained a Catholic until her death,

believed and supported him. (She had moved back to Poland from Italy in

1980, several years after his father died.)

John Max saw in his father a changed man, one able to give

voice to feelings long buried. “It was like he did a 180,” John Max says.

“He was a totally new person that I had never experienced. He discussed

his problems. He’d tell me everything that happened. He wasn’t shy about

it. He wasn’t embarrassed. He knew how to verbalize what he was thinking.

It was like the father I never had opened up.”

In the early years, John Max took photos of his father outside

the nunciature, picketed with him a couple of dozen times, and helped him

set up a website, VaticanHidesPedophiles.com. But his father was soon

making so many demands on his time—website tweaks, new photos, help

holding signs on the corner—that other parts of John Max’s life suffered.

“I support him in my heart 24/7,” he says. “But I have my own social life

to take care of, I have a house to keep up, animals to feed.”

He also has a security clearance to maintain, and he worries

that helping his father in too visible a way could put it in

jeopardy.

These days, he mostly just keeps watch over his father, a job

made easier because one of his rotating posts, as a civilian police

officer with Naval District Washington, is the Naval Observatory. At the

end of shifts there, he often stops at the curb across the street to make

sure his father is okay. As for the Secret Service officers who guard the

observatory’s main gate, he says, “I always told them with pride, ‘Hey,

you know that’s my dad standing on that corner—you look after him.’

”

When I asked whether he ever wished his father would stop, he

went silent for a while. Then he said, “I’d want him to stop, but I want

him to feel as though he’s accomplished what he needs to feel

closure.”

About six years ago, John Max bought his father a plane ticket

so they could travel together to visit Wojnowski’s daughter, Kasia, and

her family in California. Wojnowski protested at first—air travel sounded

expensive and meant time away from “work.” But he went and by all accounts

enjoyed the visit. With his family’s encouragement, he now goes every

winter.

“Once he’s here, he enjoys the grandkids,” says Kasia, who has

two young daughters. “He will read them a book. Or sit on the floor with

them for a little while. I wouldn’t say he does a lot of the initial

contact. But if they come to him and tap him or ask him something, he’ll

gladly respond.”

Such moments, however, are fleeting: “When he does come out

here, we drag him to the park and drag him to Disneyland, and he has a

blast. But sometimes I feel the next day”—when he returns to Washington

—“he’s back there outside the embassy and it’s like it never

happened.”

“I guess I always hope and pray for that Charles Dickens ‘A

Christmas Carol’ moment where my dad will ‘wake up’ and realize what he’s

missing,” she wrote to me. “Like the moment Ebenezer Scrooge wakes up

after being visited by the three spirits and is overjoyed that there is

time to make a change in his life and to benefit the people that care for

him most.”

Kasia spent eight years in the military. She married a fellow

Air Force medic and settled down in Valencia, California. She, too, is

proud of her father but questions his determination to do things the

hardest way. “I’ve told him this all along: to get an attorney, or

something other than standing out there in the middle of traffic every day

for the rest of his life.”

In her more philosophical moments, however, she believes that

for her father, fighting has become more important than winning—that

victory, if it ever comes, might rob him of the one thing that gives his

life meaning.

“This is his reason for getting up in the morning,” Kasia says.

“If the Catholic Church came crumbling down tomorrow, I’m not sure what he

would do. I’m not sure it would give him the peace he’s looking

for.”

After the Archdiocese of Washington told him in the late 1990s

that his alleged abuser—whom it did not name—had passed away, Wojnowski

wrote back asking for proof. The priest’s identity had remained a mystery.

A death certificate, with a name, would make the man something more than a

half-forgotten apparition, even as it confirmed his departure from the

world.

But his request, he says, went unanswered.

I, too, had questions about this anonymous priest and asked an

Italian interpreter in Washington to begin making phone calls to Italy. At

the Diocese of Novara, which covers Cuzzago, the bishop’s chancellor,

Father Fabrizio Poloni, gave me the name of the village rector in 1958 and

said the Church knew of no complaints against him.

A librarian in the city of Novara’s public library faxed me an

obituary. It described a priest who had spent a career in Northern Italy’s

small towns before being “crushed” in May 1967, at age 54, by an

“unforgiving disease.”

After a half dozen years in Cuzzago, the priest had been

transferred to an abbey in a town an hour’s drive to the south. According

to the obituary, the priest “was beloved by the people of that small

town”—the one with the abbey—“who, even during his short but painful

illness, assisted him lovingly, at the hospital first and then, in the

last hour of agony, at home.”

The obituary, in a church weekly, contained no photo, but an

official at a small museum in the priest’s hometown found one and e-mailed

me a copy.

On a Sunday morning in early June, I called Wojnowski and asked

whether he was interested in my findings. We agreed to meet the next

morning, and when I showed up, ten minutes early, he was sitting on his

front steps, waiting. He bolted up when he saw me, his gaze fixed on the

file folder under my arm.

“In the shade,” he said, directing me toward some bushes beside

the concrete steps. “I have cataracts.”

He slipped off his glasses and brought the papers to his face,

a finger gliding across the words. “It could have been,” he said of the

photo. But the truth was that too much time had passed. “I don’t remember

his face.” (His brother Mikolaj had no such doubts. When I e-mailed him

the photo, he wrote back, “Definitely yes.” The man in his memory was a

little heavier, but the facial features were the same.)

John Wojnowski asked if I knew anything more about the disease

that took his life.

I didn’t. The two obituaries I’d found didn’t say. Still, in

just a couple of months, the Italian interpreter and I had pried loose

details that had long evaded Wojnowski. Imagine what a lawyer in Italy

might discover, I said.

He protested that he was well past the statute of limitations.

I reminded him that the Catholic Church had offered settlements to victims

beyond those time limits. But he was unmoved. “I’d be lost in Italy,” he

said. “I never went to college; I don’t have an organized mind like you.

All I know to do is what I’m doing—nothing else.”

I asked Wojnowski what he made of the obituary—of the details

of the priest’s life and early death. He was grateful for the information,

but he said it changed little.

He saw his abuser as the product of a failed system, as much a

victim of the Church in some ways as he was. The man had succumbed to

human impulses, but the Church had given him too few tools—and too little

incentive—to control them.

“That was the culture,” Wojnowski said.

I asked whether he had forgiven the priest. We were standing

now under some trees. A car alarm sounded in the distance.

“Yes,” he said, after some moments. “I’m sure he didn’t know

how he was ruining a life.”

John Wojnowski’s first years on the corner were a trial.

Passing motorists spat, threw eggs, flipped him the middle finger. People

threatened him. They punched his signs. They called him a wacko and a

loser and a coward hiding behind a sign. They leaned out of cars and said,

“Get over it,” “Get a job,” or “Get a life.”

“I was standing here and crying very often,” he

says.

But after 2002, when the wider scandal broke, the ground seemed

to shift. Motorists began waving and honking. Pedestrians stopped to talk.

They took his homemade flyers or looked at the childhood photos he used to

carry, showing his metamorphosis from a cheerful boy to an anxious,

brooding one. A few people gave him $20 bills, one man a $100

bill.

When I joined him on the corner late one afternoon, I counted

18 supportive-sounding honks from passing cars in an hour. That evening, a

middle-aged man in a finely tailored suit nodded as he strode past and

said, “Thank you, sir. I’ve seen you out here for many years.”

For many passersby, it’s those years that leave the greatest

impression. It’s his single-mindedness, his fixity, his imperviousness to

weather, age, and changing times. He arrives at the corner by 4:45 pm and

leaves after 8 pm, a regimen you could set your watch by were it not for

the vagaries of public transportation.

The week Pope John Paul II died in 2005, Wojnowski went to the

corner as usual but left his signs at home in a gesture of respect for the

dead and the mourning. The visit of Pope Benedict XVI to Washington in

April 2008 scarcely broke Wojnowski’s stride. After Benedict’s

late-morning visit to the White House, the popemobile traveled up

Massachusetts Avenue, on its way to the nunciature. Had Wojnowski stood

along the motorcade route around noon, the pope—at whom so many of his

messages are aimed—might have caught a glimpse of his sign.

But Wojnowski was nowhere to be found. A reporter who noticed

his absence during the motorcade asked Wojnowski about it that evening, at

the usual hour, when he finally showed up.

“I never planned to be here,” Wojnowski replied. “I stick to my

routine. I have things to do.”

Church officials stopped responding to Wojnowski’s letters

years ago, but they haven’t altogether ignored him. On at least three

occasions, clergymen have approached him outside the

nunciature.

One evening not long after Wojnowski started, he says, Giorgio

Lingua, an Italian monsignor and a senior aide to the nuncio, emerged from

the embassy and pleaded with him to stop. Among the arguments Wojnowski

says Lingua offered was that the abuse may have been partly his fault. On

his website, Wojnowski, without identifying Lingua, offers the alleged

remarks as evidence of a Vatican conspiracy to expose and silence

him.

Lingua is now the nuncio to Iraq and Jordan. When I reached him

through the nunciature in Baghdad, he recalled speaking to Wojnowski but

denied making any such statements. “I did try to speak with him and he

started to tell me his story, recalling places familiar to me in northern

Italy,” Lingua wrote me in an e-mail. “One afternoon I invited him for a

walk since I wanted to understand better his story and see how I could

help him. Mr. Wojnowski initially accepted, then he refused, I do not know

why.”

Another sidewalk chat took place with Stephen J. Rossetti, a

prominent priest and licensed psychologist who issued early warnings to

the Church about the problem of sexual abuse. Wojnowski told me that when

Rossetti was head of the Saint Luke Institute, a renowned Silver

Spring-based treatment center for troubled clergy, Rossetti listened to

his story and then told him he would never get a cent from the

Church.

I reached Rossetti at DC’s Catholic University, where he

teaches pastoral theology. He told me he had heard about Wojnowski from

friends and confirmed having paid him several “pastoral visits” outside

the nunciature.

“As a church, when someone’s angry like that, it’s easy for us

to be reticent and kind of want to stay away,” says Rossetti, the author

of the 1996 book A Tragic Grace: The Catholic Church and Child Sexual

Abuse. “We have to be just the opposite and have to reach out to

someone who might be angry at us. I was hoping that to see that a priest

can be concerned and be sensitive would be helpful.”

He acknowledged downplaying Wojnowski’s chances of obtaining a

financial settlement in Washington. “If he wants some reparation,” he

says, “he needs to go to the parties responsible”—in Italy.

When I told Rossetti that Wojnowski wanted a $5-million

settlement, he let out a short laugh and said, “Yeah, right.”

“For victims to heal, based on my professional experience, they

cannot make their healing contingent on what other people do,” Rossetti

said. “As long as you let your perp control your life, then you’re going

to stay a victim. Lots of victims have moved on to become survivors

because they worked it out.”

A third set of encounters is more complex and harder to verify.

Wojnowski noted in his datebooks 17 incidents from 2007 to 2010 in which

he says Archbishop Pietro Sambi, then nuncio to the United States,

insulted him in Italian—a language both men spoke—during Sambi’s afternoon

strolls on Massachusetts Avenue. When a reporter for an online publication

asked Sambi about the alleged insults two years ago, Sambi declined to

comment.

Sambi had helped orchestrate Pope Benedict’s historic meeting,

at the nunciature, with victims of sexual abuse during the pontiff’s 2008

visit to Washington. In an address to leading clergy the next year, Sambi

said that the scandal had been “a horrible experience which has deprived

all of us of our credibility before our faithful and before

society.”

The truth about the alleged insults may never be known. Sambi,

a popular, outgoing figure, died in July 2011. What seems clear, however,

is that he and Wojnowski had a testy relationship.

Videos taken on Wojnowski’s camera phone and uploaded to

YouTube show Sambi warning Wojnowski in accented English to keep his

belongings off the nunciature’s lawn. In other videos, he’s seen coming

and going from the nunciature and staring, up close, at Wojnowski’s

camera.

“Take away this from here,” Sambi says in one video, gesturing

with his cane to Wojnowski’s bag and raising an admonitory index

finger.

“That’s state property,” Wojnowski, who is holding the camera,

can be heard replying.

“Otherwise it will disappear,” Sambi says.

Up the hill from a bus stop and the Bladensburg Industrial

Park, in a neighborhood of narrow streets, bodegas, and blue-collar homes,

is the small brick house where John Wojnowski once had a family but now

lives alone. Overgrown bushes obscure the front window, and the paint on

the gables is peeling.

I first visited on a February morning when temperatures were in

the 40s. He had warned me a few days earlier that he wouldn’t let me

inside and had brushed aside my many appeals. “I don’t want people to know

I live in such destitution,” he had said. “It’s worse than you can

imagine.”

I heeded his wishes and waited outside. At exactly the

appointed hour, he stepped out the front door.

When I asked how he was doing, he raised both hands and curled

his fingers into fists, like a man clutching the side of a ship in a

storm. “Hanging in there,” he said. “With two hands.”

Not since before the alleged abuse has faith comforted him. He

is agnostic about God, he says, and no longer Catholic.

A few days earlier, he had told me about the life he imagined

for himself if the Church were to free him from his vigil by finally

settling. “I would travel,” he said. “I would like to visit India, Machu

Picchu, see the Pyramids, the Great Wall of China, Moscow.”

Anything else? “Have a relationship with a woman,” he said.

“That would be nice.”

The more time I spent with Wojnowski, the more I came to see

the alleged abuse as a double injury. It hadn’t just claimed the life he

might have lived. It had also stolen his ability to trust the very

people—lawyers, therapists—perhaps best able to win him some measure of

justice, or peace.

“People tell me I’m fighting the good fight,” he said one

evening. But was its monotony, its ceaselessness—its single line of

fire—part of the affliction or part of the cure? Were there other paths to

redemption?

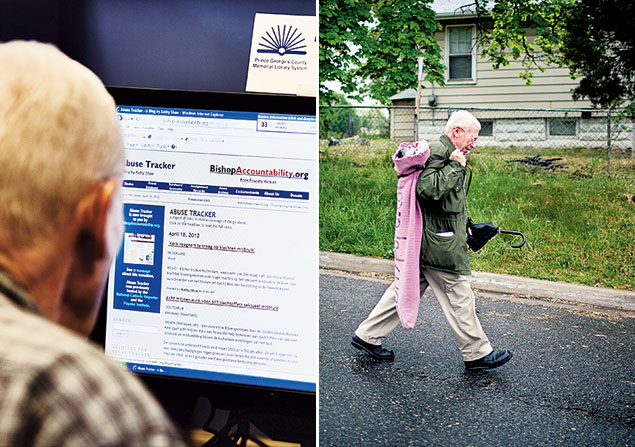

From his house that morning, Wojnowski led me on a brisk walk

to the Bladensburg branch of the Prince George’s County public library.

It’s a ten-minute stroll, past a Checkers Drive-In and through a service

alley behind a faded strip mall.

The library occupies a rectangular brick building with drop

ceilings and fluorescent lights. A banner along the bookshelves says one

world, many stories.

Wojnowski comes every day it’s open, his attendance as

unfailing here as it is outside the Vatican Embassy. He likes to arrive a

few minutes before 11 am, when it opens, to be first in line for the

computers. He spends two to three hours online before heading home for

lunch, and afterward, at precisely 3, to the nunciature.

On the day I accompanied him, Wojnowski checked the weather in

Czarnków, his late mother’s hometown, before clicking to websites with

names like Abuse Tracker and Jesus Would Be Furious. He scanned the latest

news on the global abuse scandal—which has spread to Ireland, Poland,

Italy, Holland, and elsewhere—and dropped nickels and dimes into a machine

to print articles that interested him.

The librarians seemed to have a soft spot for Wojnowski,

continually resetting the computer’s timer and shooing away patrons who

tried to claim his terminal while he was in the restroom.

A story, in the National Catholic Reporter, that held

Wojnowski’s attention for much of the day was headlined CLERICAL POWER

THWARTS VICTIMS IN POLAND. It was about the difficulties of bringing

sexual-abuse charges against priests in the country of Wojnowski’s

birth.

A few days before, Wojnowski told me, there had been just three

or four reader comments below the story. Today there were ten pages; he

printed them all, stapled them at the front desk, and slipped them into a

plastic shopping bag inside his tote.

The story was interesting, I said, but what was so compelling

about the reader comments?

Wojnowski told me they said things he lacked the means to say,

powerful things he believed could one day bring down the Church if only he

might find the words. I wondered whether that was it exactly. Wojnowski

has a wide and learned vocabulary, and the comments he pointed me

to—“horrifying church,” “the Polish hierarchy is the most arrogant”—seemed

well within his reach.

When I asked whether he reviewed and filed the printouts at

home, he told me he had time for neither.

When he returns from the nunciature, it’s 9 or 10 at night. He

has time enough for a simple meal—raw broccoli, cereal, a few squares of

baker’s chocolate—before his eyes grow heavy and he falls asleep. He needs

rest because tomorrow the cycle begins again, as it will the next day, and

the day after that. And so the papers from the library stay in the

shopping bags he brings them home in, a silent army of words he hopes, one

day, to marshal.

Contributing editor Ariel Sabar is author of the award-winning memoir “My Father’s Paradise.” Gabriella Savio served as an Italian interpreter and research assistant on this story.

This article appears in the July 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.