Bob Ehrlich is heading to the one place that may hold as much allure for him as the Maryland governor’s mansion: the Little League field. On a blue-sky afternoon, Ehrlich’s wife, Kendel, is getting sons Drew, 11, and Josh, 6, situated in their games at a park in Arnold when the former governor arrives with some aides and some news. “Good poll,” he says to his wife instead of hello. “Good poll.”

He calls up on his phone a new Rasmussen survey that has him dead even among likely voters, 45–45, with the man who ousted him four years ago and for whom he now intends to return the favor.

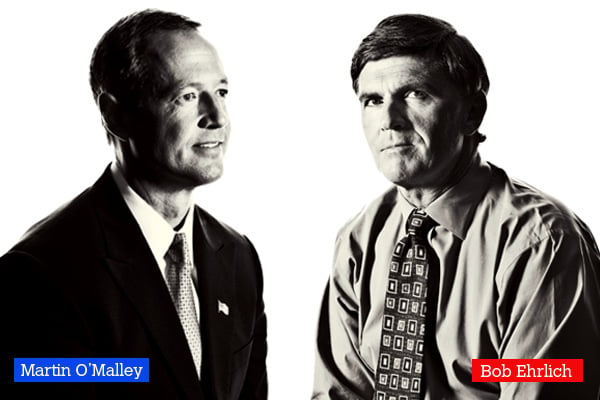

The rematch between likely GOP nominee Ehrlich, 52, and the current officeholder, Martin O’Malley, 47, is as fierce as they come, a contest between two competitive alpha males, each the dominant presence in his party. They rarely utter each other’s name. Democrat O’Malley, the former mayor of Baltimore, has dismissed Ehrlich as a “right-wing radio disc jockey,” referring to the show he hosted with his wife on Baltimore’s WBAL until July. And O’Malley launched a round of attack ads early on, one connecting Ehrlich to the BP oil spill and tagging him as an unregistered lobbyist.

Ehrlich has called O’Malley “a whiner” and his administration “a disaster.” He used his radio show over the last three years to take shots at his successor, occasionally giving airtime to a caller, “Martin from Annapolis,” who mocked O’Malley.

In their 2006 matchup, Ehrlich, who lost by 6.5 percentage points, didn’t make the customary call to concede and congratulate O’Malley until the day after the election, saying he wanted to wait until the absentee ballots were counted. “Is that unusual?” O’Malley says in an interview, where he doesn’t hide his disdain for Ehrlich. “Many would say it was.”

On this summer afternoon, with O’Malley and GOP primary challenger Brian Murphy in the way of his planned return to the state house, Ehrlich has invited a celebrity visitor to Drew’s baseball game: former Massachusetts governor and GOP presidential contender Mitt Romney, in the state for a party fundraiser that night.

It reminds Ehrlich of the time three years ago when another presidential hopeful, former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani came to Maryland for a fundraiser and stopped by Drew’s game. Giuliani arrived at the game of seven-year-olds in Cape St. Claire with reporters, cameras, and TV satellite trucks in tow. Drew came up to bat in the first inning, and his dad whispered in his ear: “Get a hit, get a hit.” The defeated governor could just see the headlines if his son fanned: EHRLICH’S KID STRIKES OUT. But Drew did him proud—a solid line drive up the middle, high-fives all around. “That’s my boy,” Ehrlich said to Giuliani.

“Drew’s used to pressure is the moral of that story,” Ehrlich says, awaiting Romney’s arrival. “He’s been used to the limelight, the pressure, his whole life.”

It’s something else the Ehrlichs have in common with the O’Malleys—families who have grown up in the public eye—and the reason both candidates play full-contact politics. “We’re ready for another one,” says 12-year-old William O’Malley, who’s been known to sit in on his dad’s staff meetings and even offer his opinions.

“I’m built for it,” Kendel Ehrlich says of political life.

Romney finally arrives at the Little League park, and the two former Republican governors stand on the sidelines. Ehrlich is so in his element that he says the big controversy of his administration will be whether or not he can still coach the Cougars, Drew’s football team, next year. “Good eye, D!” he calls to his son. “Good eye, babe!”

Switching easily between Little League and the big league he’s back in, Ehrlich tells Romney about the latest poll numbers. Likely voters. Expected voter turnout. Tied with the incumbent. Romney, at one time a frontrunner for the GOP presidential nomination, knows something about the change-ups and curve balls of election seasons. The poll is good news, he assures his fellow Republican. “But,” he says looking him in the eye, “you got a long ways to go.”

It shouldn’t even be close. In an ordinary year, the Democratic governor of Maryland—especially one who started the campaign season with a nearly $6-million cash advantage over his challenger—would have to have been caught with an intern or accepting bribes from a tobacco lobbyist to be vulnerable. The overwhelmingly blue state has only added to its ranks of registered Democrats in the past four years, and Republican statewide elected officials are as rare as an osprey on the Chesapeake Bay in winter.

“A good Democratic candidate running a good Democratic campaign in Maryland will beat a good Republican running a good campaign every time,” says Donald Norris, who chairs the public-policy department at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. Ehrlich’s win in 2002, political observers say, resulted from an unusual alignment of stars, including momentum for Republicans after 9/11 and a weak Democratic opponent in Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, incumbent Parris Glendening’s lieutenant governor. Ehrlich was an affable former Maryland delegate who’d spent the previous eight years on Capitol Hill but never lost the clunky, nasal accent that evokes his humble beginnings in Arbutus. He became the state’s first Republican governor since Spiro Agnew was elected in 1966 and only the sixth ever.

Four years later, with an electorate disenchanted with George W. Bush and the Iraq War—and a much sharper candidate in Baltimore mayor O’Malley—the Democrats were back.

But instead of coasting to a second term, O’Malley has a race on his hands. No ordinary time, the economic crisis of the last few years has cost many incumbents their jobs, and an anxious electorate facing home foreclosures, stagnant wages, and job losses has lashed out at Democrats.

“The trends are crystal clear,” says Silver Spring developer and columnist Blair Lee, a conservative Democrat whose father was lieutenant governor to Marvin Mandel as well as acting governor for a year. “The question is are they applicable to a state like Maryland,” where a substantial federal work force is somewhat insulated from economic hardships.

Since the spring, Ehrlich vs. O’Malley, round two, has been largely about jobs, with the two candidates running around in parallel universes, the incumbent trumpeting business success stories, the challenger casting a light on shuttered doors and pink slips.

Much of their focus has been on the Washington suburbs, which both candidates believe are crucial to this election. O’Malley needs a good turnout in Prince George’s, where Democrats flocked to the polls for him in 2006, delivering more than 78 percent of the county’s vote. Ehrlich needs to tap into the rich pocket of Republicans in Montgomery, second only to Baltimore County’s in number, as well as independents for an upset. Ehrlich kicked off his campaign in Rockville, opened a headquarters there in July, and tapped Mary Kane, a Potomac Republican who’d been his secretary of state, as his running mate. At a Silver Spring event to introduce Kane, nearly two dozen members of the Howard County Republican Club carpooled in to fill out the crowd.

O’Malley stuck with his lieutenant governor, Anthony Brown, a former delegate from Prince George’s County and an Iraq War veteran. And O’Malley, a Bethesda native, takes every opportunity to tout his Montgomery County bona fides. As a child, he says, he walked to Gifford’s, Peoples drugstore, Grand Union, the duckpin bowling alley: “I describe for those born post-1963 all the things that used to be in Bethesda just to prove my credentials.”

Montgomery County has also given rise to the latest wild card in the election—Chevy Chase business investor Brian Murphy, 33, whose campaign for governor as a more conservative alternative to Ehrlich received little attention until he was endorsed by Sarah Palin, whom he’d never met or talked to.

Ehrlich, who has the backing of most of the Republican establishment in the state, says he’s not worried about the challenge to his right. He says he didn’t seek Palin’s support, although many listeners to his radio show were fans of the former Alaska governor and vice-presidential candidate.

“She’s a very effective spokeswoman for a part of the base within the Republican Party,” says Ehrlich. “Her appeal cross-party is very much in question.”

Kendel Ehrlich has had a rematch in her sights from the start. “You’re not done,” she told her husband two days after he was bounced from the governor’s office. Following the Democratic sweep in 2008—when Ehrlich was pretty certain that he was, in fact, done—his wife went to the mall and bought everything she could find with inspirational slogans from Ehrlich’s heroes such as Winston Churchill, Vince Lombardi, and Teddy Roosevelt. “Never, never, never give up.” “Believe.” She scattered them around the house, even in the shower.

By winter, the reception Ehrlich was getting at speaking engagements, along with polling data and GOP statewide wins in Massachusetts, Virginia, and New Jersey, gave him enough confidence to take the leap. He’d been telling friends he missed the action, and that was obvious every time he went to lunch at McCormick & Schmick’s in Annapolis Mall and started working the room.

O’Malley says he knows he has a rough road ahead. “I think it will be a tough race,” he says in an interview in his state-house office. “These are the toughest times our country’s gone through since the Great Depression, and every family is rightly focused on their family’s needs.”

But he says his leadership, which included such bitter pills as tax increases and budget cuts, put the state in a better economic position than most: “As far as the mirror test goes—the ability to look yourself in the mirror and know you’ve made the best decisions you could make given the adversity before us, I feel very good about that.”

Although incumbents are having uphill battles around the country, he believes that the Maryland race is unique because it’s between two people who have both served as governor. “Both of us have served as incumbents, both of us have made choices, both of us have records,” he says, “and so people have a pretty stark contrast.”

“Get me that stat,” O’Malley whispers to Christian Johansson, the state secretary of business and economic development. Dan Mote, president of the University of Maryland, is rattling off statistics about the state’s prominence in the biotechnology industry as he introduces the governor at a State of Tech in the I-270 Corridor conference in June. For each fact and figure Mote utters, the governor leans over to Johansson: “Get me that stat.”

O’Malley occasionally sprinkles a verse from Irish poet Seamus Heaney into his speeches and tells a reporter he could go on reciting poetry for hours. He spends time every morning reading spiritual passages by Catholic authors and scholars such as Thomas Merton and John O’Donohue or poet Meister Eckhart “just to get going and get centered.”

But O’Malley is also inspired by numbers. His campaign speeches spill over with facts and figures that he believes add up to solid stewardship of the state: 40,000 new jobs this year . . . 24 percent lower unemployment than the national rate . . . 53 percent more in money for school construction than his predecessor . . . 60-percent increase in the blue-crab population.

When he was mayor of Baltimore, his database-management tool, CitiStat, which measured government performance, became a hallmark of his crime-fighting and budget-cutting efforts and won Harvard’s Innovations in American Government Award in 2004. As governor, he adapted the program into StateStat, and, to measure efforts related to the environment, BayStat. Last year, he was named one of Governing magazine’s public officials of the year.

But aides say he can be so much in the weeds of governing that he risks missing the connections with voters. The mayor who wore muscle shirts while playing guitar with his Celtic-rock band, O’Malley’s March—and was once tagged as being cocky and all flash and ambition—has become a more subdued governor, very disciplined and scripted and so guarded that he won’t begin an interview until a press aide is in the room.

“He’s smart enough, but nobody would mistake him for warm and fuzzy and personable,” says one Democratic elected official. “You can sit down for a long dinner with him and you don’t feel you know him any better at the end than when you sat down.”

Mixing with voters, O’Malley has the Clintonian gift of remembering names, faces, and relationships, say those who’ve watched his career, but not Bill Clinton’s charisma.

“O’Malley, for many people, is a difficult guy to love,” says Donald Norris of UMBC, “and many in the electorate just don’t get him personally. But Maryland voters tend to vote on policy preference and performance, and he’s going to campaign like hell.”

In fact, there’s a doggedness to O’Malley that has served him well as a candidate and a politician. Legislators say the governor pursues his agenda with such zeal that he once enlisted famed Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel to call a state senator on his behalf in his unsuccessful attempt to repeal the state death penalty.

And admirers say there’s a warmth and compassion to O’Malley that people don’t always see or that may have been more evident when he was mayor and closer to the streets. When 24-year-old state trooper Wesley Brown was gunned down outside an Applebee’s in Prince George’s County in June, O’Malley cut short an out-of-town trip and showed up at Brown’s mother’s home. He promised her he’d talk to the group of at-risk boys the trooper had mentored, the single request she made. One month later, the governor gave the boys a tour of his office, letting them take turns sitting in his chair, showing them photos of him with President Obama, and telling them to look after one another: “Don’t be afraid of the light that shines in you.”

O’Malley’s term has largely been shaped by economic pressures. With a friendly Democratic state legislature, he steered through a one-cent sales-tax increase in a 2007 special legislative session as well as higher income taxes on those making more than $1 million a year and on corporations.

“Was it popular?” he says. “No, it wasn’t popular. But it was necessary in order to move our state forward and protect as great a number of us as we possibly could through this recession.”

In that same session, he won approval for slot machines as a source of revenue, which Ehrlich had tried but failed to do, though no gambling operations have yet been set in place. The issue has reemerged this year: A referendum on a proposed casino for Arundel Mills Mall, which Ehrlich favors and O’Malley opposes, will be put to voters in Anne Arundel County in November.

Ehrlich’s administration was marked by frequent clashes with the heavily Democratic legislature. He failed to get a slots bill passed as O’Malley did, and high-profile medical-malpractice and energy bills were both enacted after the General Assembly overrode Ehrlich’s vetoes.

As a candidate again, Ehrlich has pledged to repeal the O’Malley sales-tax increase and make the state more welcoming to small businesses.

He started his campaign with visits to struggling small businesses around the state—visits that, fortuitously for him, came on the heels of Northrop Grumman’s selection of Virginia over Maryland for its new headquarters. At each stop, Ehrlich listened to complaints about taxes as well as heavy-handed business regulators and problems with unemployment insurance.

“We are in the process of closing the business and moving to Virginia,” Lucia Nazarian of Auto City Body Shop tells Ehrlich at a roundtable of businesswomen in Bethesda.

“Can you wait till November?” he responds. “I hear it daily—you better win or I’m gonna move.”

Ehrlich and his wife have attended several Tea Party rallies in Maryland, and he says the movement’s “pro-wealth, small-business-centric” ideals are a good fit with him. The Tea Party, however, is a likely source of momentum for Brian Murphy, who lumps O’Malley and Ehrlich together as career politicians who tax and spend too heavily.

O’Malley, for his part, has been highlighting growth—new school construction one day, an expanding business the next. Spending a day in Silver Spring in June, he toured Discovery Communications, which hired more than 500 people in the last two years; then he had lunch with community leaders at McGinty’s Pub, where he heralded Silver Spring’s redevelopment around the Metro’s Red Line. Noting that Ehrlich opposes the Purple Line as a light-rail project while he favors it, he told his lunchmates, “There’s a real clear difference between a vision for transportation that appreciates where mass transit is, especially in a state as crowded as ours, and the one the last fella had—if you want to call that a vision.”

Their political division is clear. But it’s not a big culture war. Ehrlich generally favors abortion rights—a position that left an opening for Murphy’s more conservative views—and social issues have played a minimal role in the campaign so far. They part company over fiscal matters and, more fundamentally, the role of government. O’Malley sees his office as a way of “connecting Maryland’s journey to its resources, creat

ivity, and dreams,” as he said in this year’s State of the State speech. Ehrlich sees himself as a restraint—a call of “enough”—on a system that, he says, tends to grow in a limitless way.

“They see things very differently,” says Herb Smith, a political-science professor at McDaniel College and an O’Malley appointee to the Sport Fisheries Advisory Commission. “And they’re both pretty authentic and genuine in terms of their relationship to those two worlds.”

O’Malley wasn’t a fan of The Wire, the popular HBO drama series that portrayed a bleak, at times corrupt Baltimore led by a handsome, ambitious, and at times unethical mayor. The fictional city councilman turned mayor turned governor was based on a number of politicians, Wire creator David Simon always said, but the character’s career path echoed O’Malley’s to a T. So when Mayor O’Malley was asked if he wanted to appear in a cameo, as other politicians had, he said no, according to a writer for the show.

Governor Ehrlich, on the other hand, asked if he could have a role. He ended up playing a state trooper in season four, though he says he had hoped he and his wife could play a prosecutor and a public defender so they could yell at each other.

With a low-key, comfortable manner, Ehrlich is one of the few politicians booted from office with a favorability rating of more than 50 percent.

“He has a wonderful style,” says Leon G. Billings, a former Maryland delegate who was one of the most liberal members of the legislature but had what he calls a “disarmingly pleasant” friendship with his colleague across the aisle. “It’s extraordinarily difficult to dislike Bob Ehrlich.”

Ehrlich is so casual that he shows up for a photo shoot in a red Terps polo shirt, and his aides have to find him a shirt and tie and tell him to smooth down his hair. It’s a little shaggier these days—Kendel won’t let him get a haircut, he says, because she thinks women voters like the longer hair. His staff and friends, even voters, call him “Gov.” The same freewheeling style as governor often prompted him to stray from his script even in formal speeches, adding asides and inside jokes that audiences didn’t always get.

Critics say he’s thin-skinned and point to his rocky relationship with the print media during his administration. When he felt that coverage of him was unfair and inaccurate, Ehrlich forbade state employees from speaking to two Baltimore Sun journalists. That prompted the paper to sue—unsuccessfully.

He had better relations with radio. As governor, Ehrlich frequently called in to radio shows and even did regular spots—against his staff’s wishes—on The Sports Junkies, a raucous morning-drive show that generated more comment than anything else he did, he says.

Once out of office, in a brand-new home in Annapolis and a law-firm job with North Carolina–based Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, which also employed several of his aides, Ehrlich sought a way to remain part of the conversation. He wrote a book—as yet unpublished—about his views. And he and his wife shopped a Bob and Kendel radio show, finding a home on Baltimore’s WBAL, a conservative-leaning station.

The Saturday-morning program, which Kendel has hosted without her husband since he officially filed his candidacy in July, gave the Ehrlichs their public profile back. With a mix of banter, politics, shout-outs to their sons’ sports teams, Ehrlich-friendly guests, and right-leaning listeners who compliment Kendel as much as Bob—“Thank goodness you’re running against O’Malley and not Kendel,” a caller told Bob—the show allowed them to rail against the current administration. Ehrlich says the show was so unrehearsed that he and his wife didn’t even discuss what they’d talk about during the drive to the station for the 9 am show. “I sleep,” he says. “She drives.”

Kendel does all the family driving—in part, she says, because her husband isn’t very good behind the wheel: “My kids get in the car knowing Mom’s in the driver’s seat.”

Some in Annapolis believe this is true in more ways than one.

Asked about her role in her husband’s decision to run, Kendel laughs and says, “Strong. I had a strong role. Not decisive, but I remained very optimistic that the fluke was not Bob Ehrlich getting elected; it was Bob Ehrlich getting defeated. It’s a gut thing for me. I have pretty good instincts.”

She says she felt that her husband’s return to public life was now or never: “I lost a brother to cancer early on. I learned from that you just can’t wait in life.”

The contrast between Ehrlich and O’Malley extends to their strong, intelligent, attractive wives—both lawyers and devoted mothers but different sorts of political spouses.

Catherine “Katie” O’Malley, daughter of longtime Maryland attorney general J. Joseph Curran Jr., works full-time as a district-court judge in Baltimore, a job that by law prohibits her from campaigning—and that’s not an altogether bad thing, she says: “I’ve been campaigning all my life, so it’s nice not to have to do it. Martin’s pretty good at it, so he doesn’t need my help.” She adds that her kids are active in the campaign.

The O’Malleys have four children—Grace, 19, who attends Georgetown University; Tara, 18, who’s entering Loyola University in Baltimore in the fall; William, 12; and Jack, 7. Governor O’Malley says the best parts of living in the official mansion are that he can walk his youngest son to school every morning and that there’s help for his wife. “For seven years when I was mayor, she had a disproportionate amount of the household chores,” he says. “After seven years of Katie having virtually no support at home with little kids, it’s been nice for her.”

As first lady, Katie O’Malley has championed causes—anti-bullying, truancy, buying local foods, and ending childhood hunger. Like Michelle Obama, she planted a vegetable garden to promote healthy eating—her husband is the one who goes for junk food, she says. And she tries to work out every day—either running or taking a spinning or yoga class—to keep herself sane.

While she may not make campaign speeches, she doesn’t hesitate to sing her husband’s praises or respond directly and bluntly to attacks. Asked about the frosty relationship between him and his likely opponent, she brings up an episode from the Ehrlich administration in which an aide to the then-governor posted false rumors on the Internet claiming that O’Malley was unfaithful to her. Ehrlich said at the time that he didn’t know about the postings and called for the aide’s resignation, but the first lady holds him responsible and it still rankles.

“How can you be cordial to a person like that?” she says of Ehrlich. “How can you like a man who’s hurting your family like that? It’s not going to be possible. We don’t have to like him. It’s not about that. It’s about who’s doing a better job as governor.”

Ehrlich declines to respond, saying through his press secretary that the episode has no bearing on the current contest.

Kendel Ehrlich is a fierce advocate for her husband—on the weekly radio show she continues to host, at fundraisers, and at campaign rallies. At a tax-day Tea Party rally in Towson, “she really pumped up the crowd,” says Dave Schwartz, state director of Americans for Prosperity, which organized the event, and a former Ehrlich fundraiser.

“I enjoy it, and I think people know that about us,” Kendel says of her campaign activities. “It’s sort of a family affair.”

As first lady, she worked on her own issues such as drug and alcohol abuse and mental health. But she also sometimes sat in on the governor’s meetings, weighed in on personnel and policy matters, especially those related to criminal justice, and was a major presence around Annapolis, says a former aide. When Ehrlich wanted support from then-comptroller and former governor William Donald Schaefer, he had Kendel deliver a birthday cake to the Democrat at a Board of Public Works meeting.

A former public defender and a prosecutor—as well as, surprisingly, a former Democrat—Kendel was talked about as a possible candidate for a US Senate seat in the 2006 election and says she doesn’t rule out a career as an elected official. “I don’t count that out in my future,” she says, “but it would be a while from now because my kids are young. I really believe that people should spend time with their children.”

Martin O’Malley grew up in Bethesda and Rockville, one of six children, with religion and politics as his background music. His grandparents were Democratic Party leaders in their towns. His mother, Barbara, has worked for congresswoman turned senator Barbara Mikulski for the past 40 years. And O’Malley’s late father, Thomas, was a World War II bombardier and criminal-defense lawyer who ran for Montgomery County state’s attorney in 1998 as a Republican, losing to Doug Gansler, now Maryland attorney general.

“A couple things were always understood in our house,” O’Malley says. “Every Sunday you’d go to church, and every election you’d vote.”

Before law school at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, O’Malley went to Catholic schools: Our Lady of Lourdes, where he was president of the student body, DC’s Gonzaga High School, where he made lifelong friends who are still part of his inner circle, and Catholic University.

Richard Ben Cramer, author of a book about the 1988 presidential contenders, What It Takes, recalls meeting O’Malley, who’d been working as an advance man for Colorado senator and presidential hopeful Gary Hart in Iowa: “I’d never seen such political talent. Martin had the whole damn county organized.”

O’Malley went on to work for Mikulski, as state field director of her senate campaign and then as a legislative fellow, and in 1998 he was hired as an assistant state’s attorney in Baltimore.

But he failed in his first time at bat as a candidate, losing in a bid for a state-senate seat in 1990. He ran for the Baltimore city council the following year and won, earning a reputation over the next eight years as an intense, passionate, bomb-throwing politician.

O’Malley’s 1999 bid for the mayor’s office in Baltimore shocked the predominantly African-American city—his victory at age 36 even more so. After he emerged from a crowded field to win the Democratic primary, the Washington Post proclaimed: WHITE MAN GETS MAYORAL NOMINATION IN BALTIMORE.

Mayor O’Malley won high marks for making a dent in that city’s crime rate. In 2002, at the urging of Democrats who worried that lieutenant governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend wasn’t a strong enough candidate, he flirted with the idea of running for governor. But he resisted, say those who know him, because he felt he had more to do in Baltimore—and to show voters he wasn’t all about ambition.

By that time, the praise was starting to roll in and he was being touted as a bright young star in the party: one of “the best and the brightest,” as Esquire called him in 2002, one of the top five big city mayors, as Time said in 2005. Talk of Baltimore’s dynamic mayor as a possible Vice President or even presidential candidate wasn’t far behind.

When O’Malley beat Ehrlich in the 2006 gubernatorial race—after being spared a primary fight with Montgomery County executive Doug Duncan, who bowed out of the race—his national profile was on the rise.

Four years later, much of that star power has faded as he works to hold onto his job. Walking in the heart of crowded downtown Silver Spring during lunchtime, the governor of the state is barely noticed.

“Governing in the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression will do that to you,” says McDaniel College’s Herb Smith.

Some believe that O’Malley’s support of Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic primary cost him a higher national profile. Cramer, who’s remained friends with O’Malley over the last 25 years, says the governor resisted pressure to switch horses.

“In the spring of ’08 comes a call from Martin’s erstwhile mentor, Gary Hart,” Cramer remembers. “He says, ‘Martin, you are on the wrong side of history. You have to switch to Obama right away.’ Martin says, ‘Senator, I was with you for not one, not two, but three failed presidential campaigns. What makes you think I would bolt now?’ ”

Ehrlich’s loss to O’Malley in 2006 was the first time in 16 races that the Maryland Republican had ever lost an election.

“I still haven’t recovered,” says his father, Bob Sr., a retired car salesman, Korean War veteran, and onetime Democrat.

In the rowhouse in the blue-collar town of Arbutus where they still live, Ehrlich’s parents doted on their only child. “We tried to interest Bobby in everything,” says his mother, Nancy.

He took a liking to politics, putting a Barry Goldwater sticker in the window and crying the day the 1964 Republican presidential nominee lost to Lyndon B. Johnson, but his real passion was sports.

Athletic scholarships took Ehrlich to Gilman, a private boys’ school in Baltimore, then Princeton, where he was captain of the football team.

After law school at Wake Forest, Ehrlich joined a Baltimore law firm and, in 1986, ran for the Maryland House of Delegates. Then, and in every campaign since, his parents threw themselves into the fray, showing up at events in shorts and Ehrlich T-shirts, waving signs on street corners, manning phone banks, and spending night after night knocking on doors for their son—Bob Sr. taking one side of a street, Nancy the other. “It’s effective, hon,” says Bob Sr.

Ehrlich represented parts of Baltimore County in the state legislature through 1995, earning a reputation as a moderate Republican in the image of Maryland’s late US senator Charles “Mac” Mathias. Leon Billings, a Democrat who served on the judiciary committee with Ehrlich, says, “he was one of the people I would classify as both a reasonable and responsible legislator. He didn’t seem to have a sharply defined ideology.”

In fact, Ehrlich frequently partnered with Democrats during a time of much bipartisanship.

Elected to Congress in 1994, the start of the Newt Gingrich revolution, Ehrlich had to straddle the line between the conservative GOP leadership on the Hill and the more moderate leanings of his state.

Kenneth Montague, a former Democratic delegate whom Ehrlich later appointed to head juvenile services in his administration, remembers visiting Ehrlich in Washington: “We sat down in an alcove, and he said, ‘Kenny, this place is nothing like what we had. These folks are angry. Sometimes I think they’re going to hit one another. It’s not like what we had.’ ”

Some of Ehrlich’s former colleagues said he moved to the right. “It was a little short of a metamorphosis, but a significant change,” says Billings, who also had occasional lunches with Ehrlich on Capitol Hill.

When he returned to Annapolis as the first Republican governor in 36 years, Ehrlich found himself repeatedly at odds with the Democratic legislature. Democrats say he wouldn’t compromise; they believe he could have achieved more, including a slots bill, if he had been willing to do so. He claims the legislature thwarted him. “We welcome compromise,” Ehrlich says, “but we don’t back away from confrontation.”

Asked by a caller on his radio show what would be different this time around with the same Democratic legislature, Ehrlich said, “Isn’t it better when you have dissent in democracy and kill some bad things? It’s good for the people, it’s good for the taxpayers when you have a different voice down there.”

One upshot of the Ehrlich administration was the rise of his lieutenant governor, Michael Steele, now the controversial chairman of the Republican National Committee. Ehrlich says that, though his experience with Steele was good, he’s not surprised by some of the troubles that have plagued his friend on the national stage. “Mike is irreverent and has a little bit different sense of humor, and that’s not status quo in Washington,” Ehrlich says. “Ultimately, he is going to be judged on results on November 2.”

So will the two governors. Ehrlich insists that his challenge of O’Malley is not a grudge match. And he says that the last time out, O’Malley “ran against George Bush, really.”

This time around, O’Malley has come at Ehrlich head-on with attack ads—aired in early summer, some during the Ehrlichs’ own radio show—that charged him with being a lobbyist for special interests, including big oil, while at his firm and suggested a link to the BP oil spill.

Though O’Malley was forced to admit that his campaign went too far in linking Ehrlich to the spill, he defends the tenor of the ads: “If he chooses to hide behind radio-show screeners and falsehoods and the mask of his secret government-affairs practice, then we must go after that as best we can.”

As of early August, Ehrlich hadn’t aired a single ad on radio or TV. He explains that his abstinence was due not to lack of funds but to lack of need, saying he improved in the polls with every one of O’Malley’s negative ads.

O’Malley has become more restrained since his days as mayor, when he had very public feuds with other officials. He once told reporters in a rant that the Baltimore state’s attorney should “get off her ass” and try a case. “I think I’ve done a much better job of thinking before I speak,” he says.

But there’s no mistaking the flicker in his gray-green eyes when he says of his opponent: “We took him on and we took him on very directly, and we will continue to.”

On that front, it’s an even fight.

Ehrlich—who, at his wife’s suggestion, recently read Game Change, John Heilemann and Mark Halperin’s book about the 2008 presidential election—may end an interview by talking about his son’s batting average. But his easygoing, average-guy persona leaves plenty of room for battle.

Ehrlich knows better than anyone that his opponent is an aggressive, hard-charging contender who can campaign with a vengeance. But, he says, leaning back in his chair in an office that’s three miles from the mansion he once called home, “so am I.”

This article first appeared in the September 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.