On Friday, June 16, 1972, the annual assault of heat and humidity on Washington had already begun. An undercover DC police vehicle, a light-blue 1972 four-door Ford—car #727—was cruising Georgetown with Sergeant Paul W. Leeper and officers John B. Barrett and Carl M. Shoffler, all dressed as hippies, on the lookout for street criminals doing drug deals and the like. It was best to approach possible criminals in an unremarkable car and disheveled civilian clothing.

Earlier that evening, the cops had spotted two men on Wisconsin Avenue walking briskly behind two women. Suspicious that the men might be purse snatchers, they turned their headlights off and pulled alongside the damsels in potential distress to warn them. The two women wheeled around, muttered “Narc,” and gave the cops their middle fingers.

Only a handful of crimes were reported that evening, including a series of stickups by two armed men. At Cardozo High School, a $150 calculator was reported stolen. These misdeeds were soon forgotten—but another crime committed that night remains legendary.

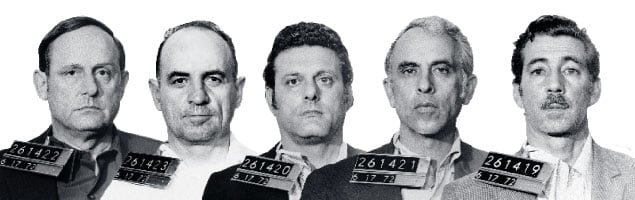

Though not reported on the Washington Post’s police blotter on June 17, five burglars, dressed in suits but wearing surgical gloves, would be arrested at the Watergate complex in Foggy Bottom by three plainclothes police officers from the “bum squad”—setting off a chain of events that changed the course of history.

While much of the story following their arrest is familiar—from the intrepid work of Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein and the secret tips of the anonymous source Deep Throat to the resignation of President Richard Nixon—the actual story of how the burglars were arrested has never been told.

It’s a tale that begins where all too many end: in a bar, this one not far from the Watergate and a favorite among police.

When the Watergate call first came from the dispatcher, Officer Shoffler radioed back, reluctantly taking the case. The address was not their primary responsibility—why wasn’t squad car 80, the vehicle responsible for the area, answering? The reply came back that car 80 was “temporarily out of service.”

In the movie All the President’s Men, the dispatcher said squad car 80 was getting gas. In their book of the same name, Woodward and Bern-stein never addressed the matter. Officer Barrett recalls the dispatcher’s saying, “Any detective car or any cruiser anywhere, [see] guard at the Watergate Hotel . . . in reference to the possible suspicious circumstances.”

Actually, squad car 80 was not out of gas. But the uniformed police officer who drove it was definitely out of service—at least according to a co-owner of PW’s Saloon, Bill Lacey.

• • •

A number of break-ins and attempted break-ins at DNC headquarters in the Watergate had been reported in the weeks leading up to that June night. Security guards had periodically found tape on interior doors, put there to keep them from locking—but applied horizontally and therefore easy for security to spot and remove. The bright boys on the Watergate break-in team just kept replacing the tape. In fact, several doors up the stairwell had been taped in such ham-fisted fashion.

The guard that night, Frank Wills—after removing the tape only to find it replaced 20 minutes later—had phoned in a report of “suspicious circumstances” to DC police just before 2 am.

The undercover cops pulled up in front of the Watergate in their unmarked car and sauntered in. The three officers thought nothing odd at this point. Hell, most of the calls they received were false alarms anyway.

The officer in charge that night, Sergeant Leeper, had on a golf hat and an old jacket bearing a George Washington University logo. At 33, he was a ten-year veteran of the force.

Across the street in the Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge, a “spotter” for the burglars, Alfred C. Baldwin III, was glued to the TV watching a horror movie, Attack of the Puppet People, on Channel 20—oblivious to the situation developing across the street. Baldwin was holed up in a disheveled seventh-floor room with a window facing the Watergate.

If squad car 80 had been in service and pulled up in front of the Watergate with lights flashing, siren wailing, and a uniformed police officer emerging from it, that surely would have pulled Baldwin’s attention away from the horror movie and likely given him time to notify the five burglars via walkie-talkie so they could have escaped and the illegal entry gone unnoticed.

Instead, by the time Baldwin noticed that things had gone awry across the street, it was too late. As Officer Barrett recalls, “We were up on the sixth floor of the DNC walking around with guns out” when Baldwin finally got on the radio and asked how Watergate burglar James W. McCord Jr. and his men were dressed.

“We’re wearing suits and ties,” McCord replied.

“Well,” Baldwin said, “you’ve got a problem because there are hippie-looking guys who’ve got guns.”

Squad car 80 operated out of the Second District station at 2301 L Street, Northwest, covering a relatively small portion of the city, and was only minutes away from any location in its patrol area. The station recently had installed its own gas tanks so police cruisers could fill up on site.

The uniformed officer driving car 80—a “black-and-white”—had pulled up earlier that evening in front of PW’s, a new bar in downtown DC. PW stood for the Prince and the Walrus, nicknames for Rick Stewart and Rich Lacey, who owned the bar with Rich’s brother, Bill.

Try as we might, my research assistant, Borko Komnenovic, and I were unable to find the police officer who drove car 80 that evening. A retired officer told us that in that era cars came and went without a lot of paperwork. Despite extensive interviews, we never found our man.

A place where young professionals gathered after work, PW’s was politely known as a “swinging singles” establishment, more bluntly as a “meat market.” The bar was a favorite of Washington’s Finest. Officers would stop by for free meals, Cokes, and alcoholic beverages—even while in uniform and on duty. “We were friendly with the local police that had that beat,” Bill Lacey recalls.

Captain William Lacey had been a career Army officer, but after he and his brother slogged through the jungles of Vietnam, the two were reassigned to Fort Belvoir, a sleepy Army base some 20 miles south of DC.

“We’ve always wanted to be Irishmen and own a saloon,” Bill, then 33, told his younger brother. Rich was eager, resourceful, and more than a tad mischievous. One evening in Vietnam, Bill had been startled to find that his brother had somehow procured a dining table, linens, crystal, fine wine, and steaks for a formal sit-down dinner in the middle of a firebase.

In DC, the Laceys and Stewart searched for an appropriate location and finally leased a place at 1136 19th Street, Northwest, where the bar Science Club is today. They worked for months getting it ready for a spring 1971 opening. Lacey used his Northern Virginia home as collateral for a loan. The three men worked with legitimate contractors, organized-crime shakedown artists, and representatives of the DC government. “Can you put a little something in my hand?” was a query the brothers say they often heard.

Finally, Bill recalls, they told both the inspectors and the man who represented a Mob protection racket to go to hell, flashing a Walther PPK pistol for emphasis. It worked—both the legal and illegal crooks vamoosed, and the La-ceys went about gutting and rebuilding PW’s for a town that was a mixture of white-collar workers and white-collar criminals, street hoods, protesters, and other people from all walks of life.

PW’s quickly became a hot spot. The walls were barnwood, the standard fare was steak and burgers, and the place reeked of bourgeois charm. Rich served as bartender and liked to mix especially strong drinks.

One day, Bill was at the bar drinking a Bloody Mary that, unknown to him, was mostly vodka with just enough tomato juice to give it color. When he finished a glass, his brother had a fresh one ready. Hours later, Bill was driving home with one eye closed.

After midnight on June 17, a policeman came in, Bill recalls, “and my brother poured him a glass of bourbon with a little Coke on top. Then he poured him another one, and another one. The policeman is sitting there, and his walkie-talkie, which was on the bar, squawked—they wanted him to investigate a burglary. He got up from the stool and could barely walk. He said, ‘How the hell am I going to investigate a burglary? I can’t even stand.’

“ ‘Piece of cake,’ my brother said. ‘Go out and get on your car radio and tell them that you’re out of fuel and you got to go back and refuel before you can respond, and somebody else will take the call.’ ”

The policeman went out, got on the radio, and said, “I’m out of fuel and I can’t respond.”

The dispatcher then contacted Sergeant Leeper’s undercover car.

• • •

Leeper and his men began their search in the basement and made their way up to the sixth floor—where the Democratic National Committee office was located. There they literally stumbled onto the Watergate Five.

Having checked each office, they were down to the final one. “Our adrenaline was starting to pump now,” Leeper recalls. Officer Barrett puts it more bluntly. When he saw a hand move toward him, Barrett says, “it scared the shit out of me.”

The cops yelled, “Hold it! You’re under arrest!” and five pairs of hands went up. One arrestee simply said, “You got us.”

The presence of five men—McCord, Frank A. Sturgis, Virgilio R. Gonzalez, Eugenio R. Martinez, and Bernard L. Barker—wearing business suits and surgical gloves and carrying electronic surveillance equipment as well as rolls of crisp, new $100 bills struck Leeper and Barrett as, well, weird. Also odd was that the burglars were all older men—in their late forties and early fifties.

The officers had only two pairs of handcuffs, so four of the burglars were cuffed together and the other, Martinez, was simply escorted out. In the process, Officer Shoffler discovered a small spiral notebook in Martinez’s jacket that had “White House” written in it.

It was 2:10 am by the time the arrest eventually heard ’round the world was made. For quite a while, police reports noted it as “the burglary at Democratic National Committee, Sixth Floor, 2600 Virginia Ave., NW.”

It was some time before it was shortened to its infamous moniker, “Watergate.”

Borko Komnenovic assisted with research for this article.

This article appears in the July 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.