In September, I was taken on a campus tour of Catholic University of America that no student should take with his or her parents.

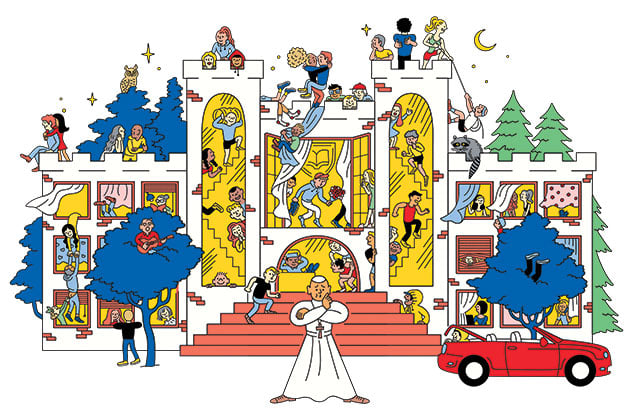

My guides were two members of an anonymous campus group called Life Is Coed. On our itinerary: an array of compromised doors and out-of-the-way windows that enterprising students might use to sneak into a dormitory reserved for the other sex.

Passing Ryan Hall, a women’s dormitory on the eastern edge of campus, one of my guides pointed to a gutter pipe he’d once climbed to reach a second-floor room. “Dangerous!” he said, almost in awe, pointing out the narrow windowsill.

At Opus Hall, the two seven-story wings—north for women, south for men—are joined by an imposing white tower with a chapel on the ground floor. But there’s also a garbage room around back, I was informed, where the fire alarm on the door is often disabled, allowing late-night visitors to enter without going past the front desk.

So it went as I trailed the two seniors through laundry rooms and common areas, where they pronounced all the windows “fair game.” Eventually, we arrived at the end of the second-floor hall in all-male Flather Hall, where a grassy slope rises to a few inches below a window ledge that even a mom or dad on an official tour might eye suspiciously. “It used to be permanently propped open,” one of my companions said.

Life Is Coed was formed in 2011, in response to the decision by Catholic’s new president, John Garvey, to resegregate the school’s residence buildings by gender. The goal, Garvey explained in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, was to bring the school back in line with Catholic morality and to reduce binge drinking and hooking up.

Garvey’s decision launched as counter-cultural an experiment as you can find on a campus today. About 90 percent of the country’s college dorms are coed. Seven schools in DC and Maryland, plus George Mason in Virginia, offer “gender-neutral” housing—that is, coed rooms.

Like any such experiment, Garvey’s was divisive from the start, not least because Catholic attracts a sizable contingent of non-Catholic students, drawn by the school’s rigorous academics and proximity to politics. And because its effects, in practice, go beyond sexual morality: The new rules inhibit the kind of late-night group study sessions that are par for the course at campuses across the US.

The policy’s fiercest critics hypothesized that Garvey—Catholic’s first lay president in decades and a onetime supporter of pro-choice presidential candidate John Kerry—was out to prove his traditionalist bona fides to Catholic’s board of trustees. (Victor Nakas, the university’s spokesman, calls this notion “completely ridiculous.”)

There was plenty of support for the single-sex dorms, too, especially from members of the so-called “God squad,” the devout students most likely to show up for morning Mass at St. Vincent de Paul Chapel. Regina Conley, then editor of the student newspaper the Tower, told the website Inside Higher Ed that some, including her, “think it’s a big step toward higher moral and academic standards.”

But along the way, Garvey’s policy ran into the law of unintended consequences: As residential life was yanked back in time, students rediscovered the lost art of dorm-room infiltration—tactics that would have been familiar to students in their grandparents’ time.

This fall, the freshmen first subjected to Garvey’s switch became seniors. In nearly two dozen interviews, current and former students and university employees explained that Catholic students living the new policy have continued to do what they’ve done for decades: act like college kids, finding ingenious ways around the rules, while the administration indulges in what one longtime staffer calls willful ignorance.

“It’s a very strange Catholic world, hard to explain to people,” says the staffer. “I’ve always found that, generally, they don’t want to know stuff.”

• • •

Founded in 1887, Catholic first admitted a woman in 1924—long before Georgetown, the Jesuit institution across town. By the late 1960s, under the liberalizing influence of the Church’s Second Vatican Council, Catholic was a relatively progressive place, despite a curfew of 9 pm for men and 7:30 for women, according to one alum’s recollection.

Charles Kaminski, who graduated in 1969, says “heavy petting” and equally heavy drinking went on mostly off-campus, at sorority and fraternity parties. “We’d make this big punch out of grain alcohol and fruit drinks— guess now you’d call it a Long Island iced tea,” says Kaminski, a retired architect in San Diego.

Dorms remained single-sex until 1980. Subterfuge was common. “People would prop open a back door or climb in a window,” says Joseph Galati, who arrived at Catholic in the late ’70s. The administration, Galati says, ignored all but the most egregious offenses. “I never knew anybody to get in trouble because they were in a dorm after hours.”

Under today’s “visitation” rules, undergraduates living on campus may not have guests of either sex after midnight on weeknights or 2 am on weekends. Enforcement has a high-tech component: Anyone entering most doors, elevators, or stairwells has to swipe in with a key card, even when passing the student or professional guards posted at a dorm’s front desk. Resident assistants make hallway rounds about every two hours.

But this shield has glaring gaps. Several seniors told me of two women’s dorms where the first-floor windows were such popular points of entry in the first year of the new rules that the rooms’ occupants had the idea to start charging $1 admission. Key cards are programmed to admit students only to their own dorms, but once they’re inside Opus, which is split down the middle, it’s not difficult to swap cards with a member of the opposite sex and swipe into the other wing.

Senior Conner Guyer says he has given his card to guys he’s met in clubs, then talked his way past the desk, saying he forgot it. Another senior, Quinn Prunty, discovered that the desk guards weren’t able to swipe into the elevators or stairwells. “If you ran by them really quick and shut the door,” she says, “they wouldn’t be able to chase after you.”

The guards are also flexible: Prunty says a friend once offered his girlfriend’s dorm guard $5 to turn a blind eye. “Okay, I’ll just go to the bathroom,” the guard agreed, “and when I come back you’ll just not be here.”

In any case, says a Life Is Coed founder, the guards go off duty at 2 am, after which “you could just let people in.”

RAs, too, vary in their restrictiveness. “Last year we had a fire drill at like 3 am,” recalls Prunty, “and the RA came down with her boyfriend. After that, it was just kind of an unspoken agreement.”

• • •

Catholic’s restrictions on contact between the sexes don’t end with residential living. The same students who prop open windows in the name of coed fraternization are also left to handle more serious matters. In keeping with the Church’s teaching, birth control is unavailable on campus, prompting Life Is Coed to begin clandestine condom drops. Nor is Life Is Coed the only advocacy group that’s unrecognized: In 2012, the administration refused to approve CUAllies, an LGBTQ group.

The Life Is Coed members and others also argue that the administration’s rigidity puts a chill on the reporting of non-consensual sex. The Department of Education announced in May that Catholic University is one of 55 schools being probed after junior Erin Cavalier filed a Title IX complaint over the university’s handling of her sexual-assault allegations.

Cavalier has made her own name public, but, says 2014 graduate Ryan Fecteau, now running for state representative in Maine: “How can you as a university tell students to come forward when the campus policy outright bans sex, period?” Fecteau was one of two recent grads who told of assault cases that went unreported during their time on campus.

“There’s a lot of shame,” says Callie Barfield, a ’13 grad who ran Students for Choice, another unrecognized campus group. “Single-sex dorms are just one part in creating that fear and shame.”

Spokesman Victor Nakas says Catholic has been “very clear” in encouraging students to report sexual assault. And, he notes, campus assaults are under-reported nationwide, at schools with all sorts of residential-life policies: “There is no evidence that our disapproval of sex outside marriage deters reporting or cooperation in investigations about sexual assault.”

Research on the effects of single-sex dorms is sparse—in part because so few students live in them. In his Wall Street Journal article, Garvey referred to a survey by Brigham Young University researchers that found students in coed dorms were twice as likely to binge on alcohol. But the study sampled only 68 students living in single-sex dorms, as opposed to 442 whose dorms were mixed. Other studies have shown that men, at least in small groups, drink less when women are around.

Nakas, citing the university’s records for a national campus survey on alcohol and drug use, says there’s been a “modest” decrease in binge drinking since single-sex dorms were introduced.

“We believe our approach [to student development], of which single-sex residence halls are just one component, is right for all of our students and also aligns with our mission as the national university of the Catholic Church,” Nakas says.

Nearly everyone I talked to confessed to feeling annoyed, and occasionally imprisoned, by Garvey’s rules. But most seniors seem to have adapted. “We were able to walk around in our pajamas if we wanted to,” says one who was initially skeptical about her all-female dorm.

“Honestly, after freshman year it really didn’t bother me,” says another. “If you want boys in your room after hours, they’ll still be there.”

Britt Peterson (@brittkpeterson on Twitter) is the Word columnist for the Boston Globe and a culture and ideas writer in DC. This article appears in the November 2014 issue of Washingtonian.