One day in 1985, Ken Rietz was driving in Los Angeles. “I was calmly turning a corner on La Cienega Boulevard,” he says, “and almost ran over a family crossing the street.”

The public-relations executive and political-campaign manager realized that his eye disease, retinitis pigmentosa, was heading toward blindness.

“I didn’t hit anybody,” Rietz says. “But I never drove a car again.”

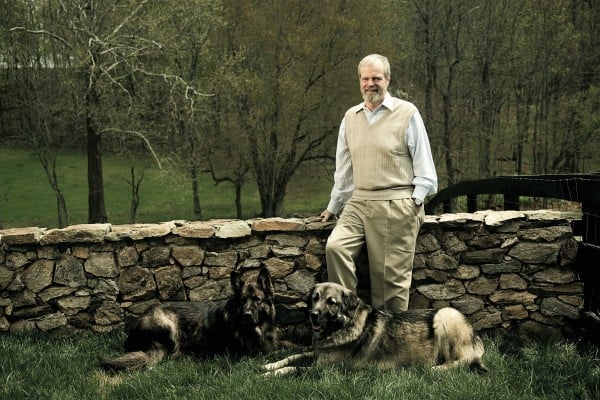

Retired after 16 years as a Burson-Marsteller executive, Rietz now runs his own public-relations firm, PSS Strategies. He has become nearly blind.

Rietz was born in Appleton, Wisconsin, and raised in Oshkosh. His father was a mail carrier, his mother a homemaker and part-time secretary. He attended the US Naval Academy but left after six months for medical reasons unrelated to vision. He then attended George Washington University but left during his senior year, in 1964, to work on Wilbur Renk’s campaign in Wisconsin to defeat incumbent senator William Proxmire.

Rietz has worked on more than a dozen races for House and Senate seats; he has also worked for the Republican National Committee and was a senior adviser for Fred Thompson’s recent presidential campaign.

His passion has become the Foundation Fighting Blindness. He is a member of its board of directors and helped establish For the Love of Sight, its annual Washington fundraiser. He has also served on the boards of the Federal City Council and the Fund for American Studies.

Rietz is married to Ursula Landsrath, “who takes care of all our dogs, our farm, and generally manages our life.” A son from a previous marriage, K.C., works in real estate in Fort Lauderdale.

Rietz lives in Delaplane, Virginia, 50 miles west of Washington. His office is in the basement of a Colonial-era church that was set for demolition before Rietz bought and restored it. It’s now registered with the Virginia Trust as a historic building.

He talked in the church’s basement about what he’s learned.

When did you find out you were going blind?

In 1976, I was living in California and was an active tennis player. I could still play fine, seeing the ball moving across the net, but I couldn’t see it lying on the court. Naturally, I felt kind of stupid and began to wonder what was happening.

I learned I had retinitis pigmentosa, or RP. It creates tunnel vision. So if I wasn’t looking directly at something, I couldn’t see it. I couldn’t find balls on the court because I had very little peripheral vision. A doctor tested my eyes, found I had good straight-ahead vision, and proclaimed that nothing was wrong.

I went to see two more doctors. Finally, one asked to look right into my eyes. He could see the RP when looking at my retinas. I had never heard of the disease.

He told me that it meant I would go blind. I was 35 years old, an athlete, active in every phase of life. I asked, “What can you do about it?”

He responded with those words a patient hates to hear: “There’s really nothing that can be done. Just go out and see as much of the world as you can while you can still see.”

I didn’t like that answer. Besides, it’s not correct. There’s a lot that can be done about the two diseases of the retina—retinitis pigmentosa, which destroys peripheral vision, and macular degeneration, which destroys central vision. That’s why I became active in the Foundation Fighting Blindness, whose research is helping to solve these diseases and give people back their sight.

Later, I learned that I’ve probably had RP my entire life. Things happened to me growing up that I couldn’t figure out at the time, but this explained it. For instance, I was a really good basketball player but couldn’t dribble. I just figured everybody saw the same way I did.

What was your emotional reaction when the doctor diagnosed the disease?

I felt that my life as I’d known it was coming to an end. And it was.

Yet back then I could still see, read, even play some tennis. Nine years later, around 1985, my life fundamentally changed. It was then that I lost my night vision and almost all of my peripheral vision. I couldn’t drive anymore.

I’m a pretty positive guy, so I began working on the problem. I got into the best eye clinic at UCLA and underwent a series of studies and examinations.

I wasn’t depressed long because I was taking action. At the Jules Stein Eye Institute, I became something of a guinea pig, volunteering for anything that had a chance of working. The researchers had me wear contact lenses with one colored lens to determine whether sunlight affected eyes with RP. Getting involved in such research helped me psychologically.

What was the biggest problem?

Moving around. I did fine in a meeting or living room, but if I had to move from one place to another, I’d trip over or run into things.

How did you get around LA?

By taxicab. I got to be known as the king of cabs. Later, when the public-relations company I owned merged into Burson-Marsteller, it provided a car and driver for me.

I excelled at faking it. Being in public relations and advertising, I figured that if people knew I couldn’t see, they’d be more reluctant to hire me.

All that changed 20 years ago when I met Ursula, now my wife. After a year with her, tripping over everything, I told her about my vision problem. She urged me to tell everyone.

Until then, I had told nobody. I just went through life stumbling and banging into things. People thought I was just awkward or sometimes rude. They’d come up to me at a cocktail party, and I wouldn’t even say hello. When someone extended his or her hand to shake, I ignored it because by then I’d lost all peripheral vision and couldn’t even see below my nose.

When Ursula urged me to start telling people, everything changed. Instead of considering me rude and awkward, they thought I was overcoming a big obstacle.

Why didn’t you do that from the start?

I was afraid to—partly because of my pride but largely because of my business. Going blind is a bad image. Clients and potential clients would look at me differently—or so I thought. As it turned out, no one ever did.

What did you do about reading?

I can still read—but barely, out of one eye, one word at a time, with computer-generated enlarged type. I lack any field of vision.

How could you work in public relations all those years? Isn’t your profession all about visuals?

Until I retired in 2006, I worked for Burson-Marsteller, which gave me great support. I’d walk in to pitch new business while holding a staff person’s arm.

During my years in public relations, I always concentrated on strategy. You don’t need perfect sight to do that, because working out a strategy happens in the mind, requiring vision rather than sight.

I’d opt out of choosing logos and that kind of stuff. I sat through hundreds of PowerPoint presentations that I couldn’t see. Actually, I considered it a relief not to see a PowerPoint presentation.

What have you learned about coping with a disability?

Go out and find out everything about your disease or condition. That way, you’ll know what actions to take and ways to advance the research.

Talk to everyone. Being in public relations, I worked a lot in Las Vegas. It was there that I met a casino executive who has RP. One time, he asked if I had my cataracts taken off. I hadn’t, because I knew nothing about that. Having that done helped my eyesight for years.

Maintain a positive attitude. It helped me to read about how others coped with their disabilities. Many people overcome obstacles—going blind, losing a limb. That helped me readjust my life. I realized I could no longer do everything. But some friends with RP still ski. Others ride horses.

Is it harder to lose your vision than to be born blind?

I’d say so. If you’re born a certain way, you adjust your life to that way. You don’t miss what you’ve lost because you never had it to lose.

Is the government doing a lot in this field?

Nowhere near enough. Around 9 million Americans are visually impaired, the majority with macular degeneration. And that number continues to rise as the population ages.

More money for research will lead to more breakthroughs. This will lead to more productivity for more Americans.

That’s why the Foundation Fighting Blindness has pushed to fund its own research on these diseases. The foundation—started 25 years ago by Gordon Gund, who owned the Cleveland Cavaliers—has funded more than $250 million in research so far. Our grants go to universities and researchers who work closely with the National Eye Institute and the National Institutes of Health.

What have you learned about being disabled?

The biggest lesson I’ve learned about coping with a disability is this: You can. You can cope successfully if you adopt a positive attitude, research the field to find out the best treatment, and adjust your life to your new condition.

My wife taught me the second big lesson: Don’t fake it. If you get a disability or disease, okay—talk about it. Don’t try to hide it.

Once I admitted I was visually impaired, people became very sympathetic. Many shared stories about their relatives—partly to connect with me but also as a chance to tell about their family: “Oh, my grandmother had this condition.”

Is there any other upside?

I look back on my two careers, in public relations and political-campaign management, and detect that I did okay in both partly because of my disability. Having tunnel vision forced me to have tunnel focus on key problems.

My lack of peripheral vision helped me ignore peripheral activities. My staff always claimed that I could sit in a conference, listen to the reports and chatter, and then ask about the underlying problems. Maybe that was just staff flattery, but I like to think it had some truth to it.

The disability enabled me to meet so many nice, generous people. I’ve learned how really good people are. They’re willing—even eager—to help you once they understand you have a problem.

This article is from the June 2008 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from the issue, click here.