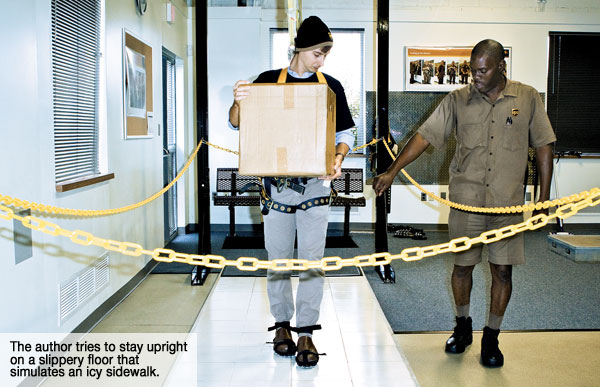

I am going down. The ground beneath me is giving out, my feet are slipping, and I’m carrying a box marked fragile. My trainer shouts: “Eyes forward—get your footing back!” But it’s too late.

The slick floor is meant to simulate an icy sidewalk, one of the many stations here that new UPS drivers must master during a week of training at the company’s new boot camp in Landover.

In front of the training facility is a flagpole, stars and stripes on top; below is a smaller flag of that familiar deep brown. Tom Conard, the facility’s manager, greets me at the door: “Welcome to Integrad.”

The wide-open space in front of us resembles a car showroom with its bright lights and white walls. There are posters with such titles as "Eight Keys to Lifting and Lowering." In the middle of the floor are UPS trucks with clear siding. Would-be drivers sort the packages inside while a trainer stands by with a stopwatch. Other driver candidates pull hand carts up fake curbs and knock on fake doors. “Hello—UPS!” they shout. They drop off fake packages, walk away, then do it again.

I hear a rubbery screech and the clang of metal. I look around the corner of a truck and see a man in a full-body harness walking cautiously. His heel gives out, and he tumbles backward before being caught by the harness. I watch him dangle in the air.

“That’s the slips-and-falls track,” says Conard. “A fan favorite. Don’t worry—you’ll get your shot a little later.”

But first, he says, is something a little easier. They call it the “on/off car.” It’s a truck with sensors on the handrails, the step, and the floor that calculate the weight you’re putting on your legs when disembarking.

Perhaps even more dangerous than an icy sidewalk is the repetitive stressing of a driver’s joints. This station shows the candidates how much extra weight they take on when not abiding by the “three points of contact” rule.

Conard demonstrates. Point number one: hand on the handrail. Number two: left foot on the bottom step. Number three: right foot on the ground. Distribute your weight across these three points. “In other words,” says Conard, “don’t just hop off.”

I give it a try. Without the three points of contact, my 150-pound body hits the ground with 237 pounds of force. I try again, gripping the handrail, one foot on the step and the other carefully reaching the ground. This time: 140 pounds.

Beside the force-floor station is a large poster with a series of calculations: Without three points of contact, a 170-pound driver will exert 136 extra pounds with each stop. At 105 stops a day, that’s 14,280 extra pounds a day. Next to the 14,280 number is a picture of three Ford F-150 trucks.

The chart multiplies this number by times per week, per month, per year, up through a 20-year career: 74,256,000 extra pounds. Below this is a picture of a cruise ship.

The poster is my first brush with the “numbers culture” at UPS, an obsession with measurements, timetables, stopwatches. The company prides itself on its adherence to a set of guidelines: arithmetically timed routes, methodical memorization. Unapologetic micromanagement.

This culture is outlined in the company’s “340 Methods,” which date to the 1920s and tell drivers the most efficient way to do just about anything. (There now are more than 340.) Such as buckling your seat belt with your left hand while starting the ignition with your right. And beeping your horn every three seconds when backing up for safety.

Integrad was created to preserve the 340 Methods the company has relied on for decades. For a while, they were in danger.

Seven years ago, UPS realized it had a problem. A driver problem.

Drivers are the nerve stem of the shipping system, the last leg in a package’s journey. And they were dropping like flies.

Before the training program began in 2007, the turnover rate of first-year drivers was 30 to 35 percent. The number of new drivers who quit after just a month on the job jumped. Accidents, injuries, the time it took for new drivers to reach proficiency standards—all were getting worse.

So what was wrong? Not the pay. A first-year UPS driver earns $35,000 to $42,000 a year, with drivers across the country averaging $70,000. Was it the young ones themselves, an entire generation of failed drivers? Or the 340 Methods—were they too archaic, too preachy?

The answer, the company would learn, was not what it was teaching but how.

Until the creation of Integrad, the 340 Methods were taught in a multi-day lecture. A literature review and several focus groups found that today’s twentysomethings—computer-savvy, hands-on—learn best by doing. Instead of telling them how much extra weight they’re taking on by not using three points of contact, why not let them see for themselves?

UPS executives worked with an MIT team, design students at Virginia Tech, and a $1.8-million grant from the Department of Labor to craft a curriculum that could capture the attention of a new generation. Hands-on training, competitive goals, teamwork, even video games would play a role. They commandeered an abandoned payroll site in Landover that had been closed for years.

In September 2007, the $34-million training center opened. The program was christened Integrated Enhanced Hands-On Learning Using Technology Designed for Candidate Graduation and Completion. Integrad for short.

Today recruits from across the Mid-Atlantic train at Integrad for one week, staying in a nearby hotel, waking before dawn each morning to learn the ropes before a final assessment. The first-year turnover rate for drivers trained at Integrad is less than 10 percent, compared with 35 percent for others before Integrad started. In September, a new Integrad outside Chicago welcomed its inaugural class from the surrounding region.

“Managers now don’t want somebody who didn’t go to Integrad,” Conard says. The grand plan, he says, is to open as many as a dozen facilities across the country.

Walking through the halls, Conard comes to a wall with class pictures from the last three years. The graduates look proud, standing in front of a package car (UPS vernacular for truck) in their brown uniforms. As he gazes at these photos, Conard looks proud, too. He’s been with UPS for 30 years, first as a loader, then a driver, now a manager.

“I was proud of the old type of training I used to do,” he says. “But the people who graduated from that program don’t hold a candle even to the people who are disqualified from here.” In other words, if your package is late or you’ve seen a driver slacking off, he or she probably didn’t go to Integrad.

This week, Conard is working with a class of 20 candidates. It’s Tuesday, their second day of training. Many are advancing from jobs as loaders or sorters. Some come from other companies, such as Fred Jones, who drove for FedEx for ten years.

“There’s no comparison,” says Jones of his Integrad experience and his training at FedEx. “There, it was a one-week course, but it was more geared toward processing packages. There was no driving.”

Integrad is a little like boot camp. Grooming and uniforms are inspected each morning; anyone not in compliance by Wednesday goes home. The program has worked so well that UPS has started farming out weekly spots to other companies, including Frito-Lay and Pepsi, so they can train their own drivers.

The next station I attempt is Selection Methods. Here candidates park, get a package, and exit the truck. It’s harder than it sounds.

Doing the sequence right requires following the rules: Hit the blinker, apply the brakes, pull over and park, engage the parking brake, unbuckle your seat belt, remove your keys, unlock the package door, grab a box, close the package door, get your DIAD (Delivery Information Acquisition Device—the electronic signature pad), and disembark using the three points of contact. In less than 15.5 seconds.

When I try, I forget the emergency brake. I fumble with the keys. I can’t unlock the door. I almost drop the DIAD. I exit the truck balancing a package, the DIAD, and my keys in a precarious cradle while the package door remains open behind me. And I forget my three points of contact.

“I don’t even want to tell you your time,” Conard says, clicking his stopwatch. “Let me show you how it’s done.”

To watch Conard complete the exercise is like observing a brown-suited ballet. His hands work in tandem, one grabbing the parking brake as the other unbuckles his seat belt. Keys are twisted and packages retrieved so effortlessly that it must be pure muscle memory at work. The whole spectacle appears as one prolonged motion, no stopping or stalling, just unwavering, precisely choreographed movement. He secures the package under his arm while reaching for the DIAD. Three points of contact, and he has seconds to spare.

He dangles the keys out for me. “And always keep the key ring on your ring finger,” he says, “so it’s always in the same place and you don’t have to go looking for it.”

My next try goes more smoothly. The package is under my arm, and I grip the DIAD tightly. I hop off expecting praise, but Conard says I still forgot something: “Three points of contact.”

My time is 16.5 seconds.

“There’s very little fat in our system,” Conard says. “Everything’s down to the second.” He’s standing beside a chart of color-coded schedules. Each minute of the candidates’ week here is planned out. “We like to think our customers set their clocks by when the UPS guy comes.”

Helping with that task is the DIAD. At some point, you’ve probably scribbled on its plastic screen with a stylus.

When you hand it back, it records the delivery. It also records the time of delivery, which is important because the DIAD knows when each package should be delivered. If the driver is late, a message pops up asking why. There are codes for answers: CL1 (building closed), NSS (no such street), OS (overweight).

Conard leads me to a cubicle where two candidates watch a driving simulation. As they sit behind virtual steering wheels, they press their fingers to parts of the screen rapidly.

“It’s a touchscreen hazard-identification game,” says Conard. “They gotta click on the obstacles to avoid them.”

One of the candidates is leaning forward. He clicks on a pedestrian crossing the road. A car pulling out of its space. But he gets the game over screen and realizes he missed a car changing lanes in the rearview mirror.

“What?” he says, leaning back. “Oh, man—it got me!”

They’re having fun. And while you probably won’t find the simulation released on a PlayStation anytime soon, it is in fact a video game. Different levels, environments, even bonus points at the end.

But the game is only a brief respite from the more tactical challenges such as the slips-and-falls track.

An Integrad trainer straps me into the bungee harness. He attaches Teflon bottoms to my shoes. Then he takes a can of furniture polish, shakes it, and lays down a thick coating on the tile track in front of me. I’ve been a little cocky until this point, citing my background in New England winters.

“Yeah, okay,” says the trainer. “It’s the confident ones I like to watch most.” He gives the bottom of my shoes an extra spray of polish.

It ends predictably, with me swaying by the ropes above. The package, though, is safe. Conard says just about everybody falls the first time, until he or she learns the correct way to walk: shuffling inch by inch, barely lifting your feet up, staring forward.

The last stop is “Clarkville.” It’s a miniature village in Integrad’s parking lot. Here, drivers are asked to make five stops, combining the information they’ve gathered at the other stations.

They’ll back up to a dock, drop off a package at a UPS box, make a delivery to a house, and more. All the while, Integrad trainers distract them by throwing footballs or placing traffic cones behind them to represent pedestrians.

“Someone gets run over most weeks,” Conard says.

This is where the final assessment will take place on Thursday. But it’s only Tuesday, so there’s still room for error. The candidates board their package cars. A trainer shouts, “Go!” and they’re off. They have 19 minutes to complete the course. They start with 100 points and get deductions for mistakes. Anything below 85 is failing. There are deductions for not using three points of contact, for taking too long to get out of the truck, for not identifying obstacles.

As five brown trucks zip around the course, I see the whole of Integrad’s purpose. The routines—the methods UPS so prides itself on—are alive and well. And the driver candidates, pushed to their limits via stopwatches and scores, are proud to be part of it. The challenges here demand something more from them—something measured to the half second, something close to perfect. These packages will arrive on time.

This article first appeared in the December 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.