Part One

The sun was just beginning to fade when David Riley pulled up to the little house off Route 354. The Virginia State Police detective got out of his unmarked Ford Fairmont and took in the setting of the mystery that had brought him here—a low-slung home shrouded in trees and underbrush. Across the street, a cemetery.

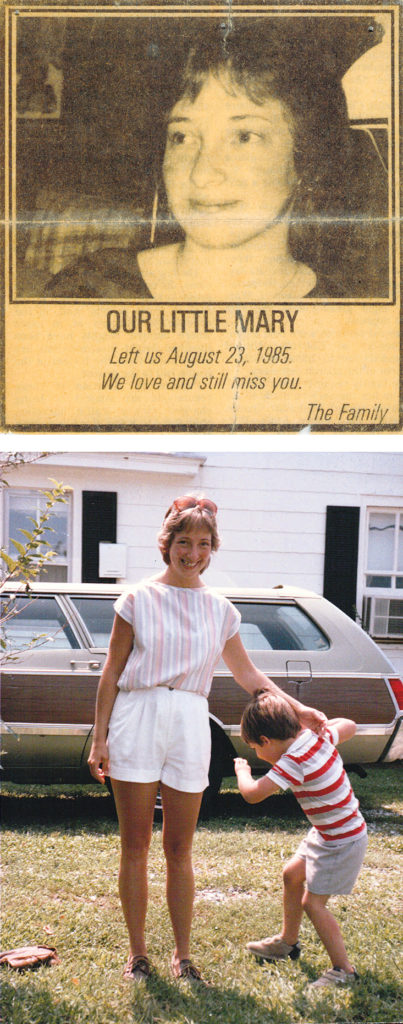

It was Friday, August 23, 1985, and earlier that day, the local sheriff’s office in Lancaster County had gotten a disturbing call: Mary Keyser Harding was missing.

A 24-year-old mother of two, Mary was a bookkeeper at the local bank. She also shouldered the weekday parenting while her husband, a commercial fisherman, was out to sea. She hadn’t dropped her kids off at the sitters’ that morning, so the children’s great-grandmother went by the house. Mary’s four-year-old son, Ray, answered the door. “Momma is gone,” he said.

Ray and his one-year-old sister were in the house alone. The little boy’s chicken dinner from the night before sat on the table. A dusting of Comet lay unrinsed in the bathroom sink. The TV was on.

By the time Detective Riley arrived, Mary’s husband, Emerson Harding, had returned to shore. Her panicked family and friends had been in and out of the house for hours. In rural Lancaster County, population 10,000, word traveled faster than the mayflies. But now Lancaster’s sprawling topography felt daunting. A patchwork of corn and soybean fields, interrupted only by thick bands of scrub pines and maples, blanketed the area. Beyond all that was the water, where most of the men in town made a living. Some fished from big corporate ships on the Chesapeake Bay. Others crabbed and oystered on the Rappahannock River, their bounty destined for dinner plates in Washington, 115 miles away.

The trade set a predictable rhythm for life on the peninsula. Though their husbands were gone much of the time, few wives worried about being alone. Crime was limited mostly to thefts and other petty offenses. The disappearance of a young mother was like a boulder plummeting into a still pond.

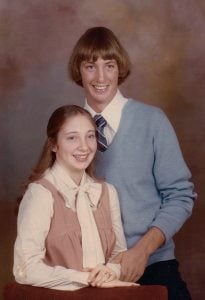

Pretty and blue-eyed, Mary had been homecoming queen of Lancaster High.

Pretty and blue-eyed, Mary had been homecoming queen of Lancaster High, class of 1978. Despite her five-foot-two, 100-pound frame, she also dominated on the basketball and softball teams. She was the fifth of the nine Keyser kids. Her father was an appliance repairman. Her mother worked as a waitress and mail carrier until she was gravely injured in a car accident. After that, Mary became the stand-in mom to her four younger brothers—checking homework, cooking dinner, and pushing them, in her playful way, to explore their curiosities. Once, four-year-old John asked about pepper—could it really make you sneeze? “Let’s find out,” said Mary, grinning.

She and Emerson started dating in high school. He was a year behind her, more than six feet tall and as quiet as she was outgoing. After graduation, Mary enrolled at North Carolina Wesleyan on a softball scholarship. But college didn’t take, and the couple missed each other. Mary got pregnant and moved back home to start her life as a wife and mother.

Anyone who knew her couldn’t fathom that she’d ever abandon her kids. As Detective Riley made his way around the Hardings’ property, he didn’t think that was possible, either.

Outside by the back door, he saw a litter box, its contents splattered across the dirt, as if Mary had been startled, then dropped it while taking it outside. Nearby, he found one of her white flip-flops. The other one was out front by the driveway. To Riley, the conclusion was obvious: Someone had taken her.

Over the weekend, search parties fanned out. They moved through the woods around the cemetery and stomped through the late-summer cornstalks, tying ribbons around trees to signal where they’d checked. She could be out in the water, everyone knew that. But they tried to imagine finding her on land, maybe injured or kidnapped but alive.

When two days of scouring turned up nothing, the mood around town darkened. Lancaster was a place where the local convenience store would let you run up a tab of $400 or $500, where kids ran free until sundown, when their parents would whistle for them to come home. Now neighbors were sizing one another up.

Riley was doing the same. The 37-year-old detective was a second-generation law-enforcement officer known for his swagger. He’d been with the state police nearly 15 years, several of which he’d spent investigating major crimes such as murders and rapes. It was a level of experience the Lancaster cops lacked—experience that now seemed essential.

By August 27, four days after Mary vanished, Riley had brought in a Cessna to aid the search. That afternoon, he was up in the airplane when its radio spit out an alert: A body had been found in the Rappahannock, just off the coast of a marshy area called Belle Isle.

“We flew as low as we could,” Riley remembers. There it was, floating face down in water so shallow he could see straight to the river bottom.

“The body was badly decomposed,” says Riley. “Extremely bloated, probably double the normal size.”

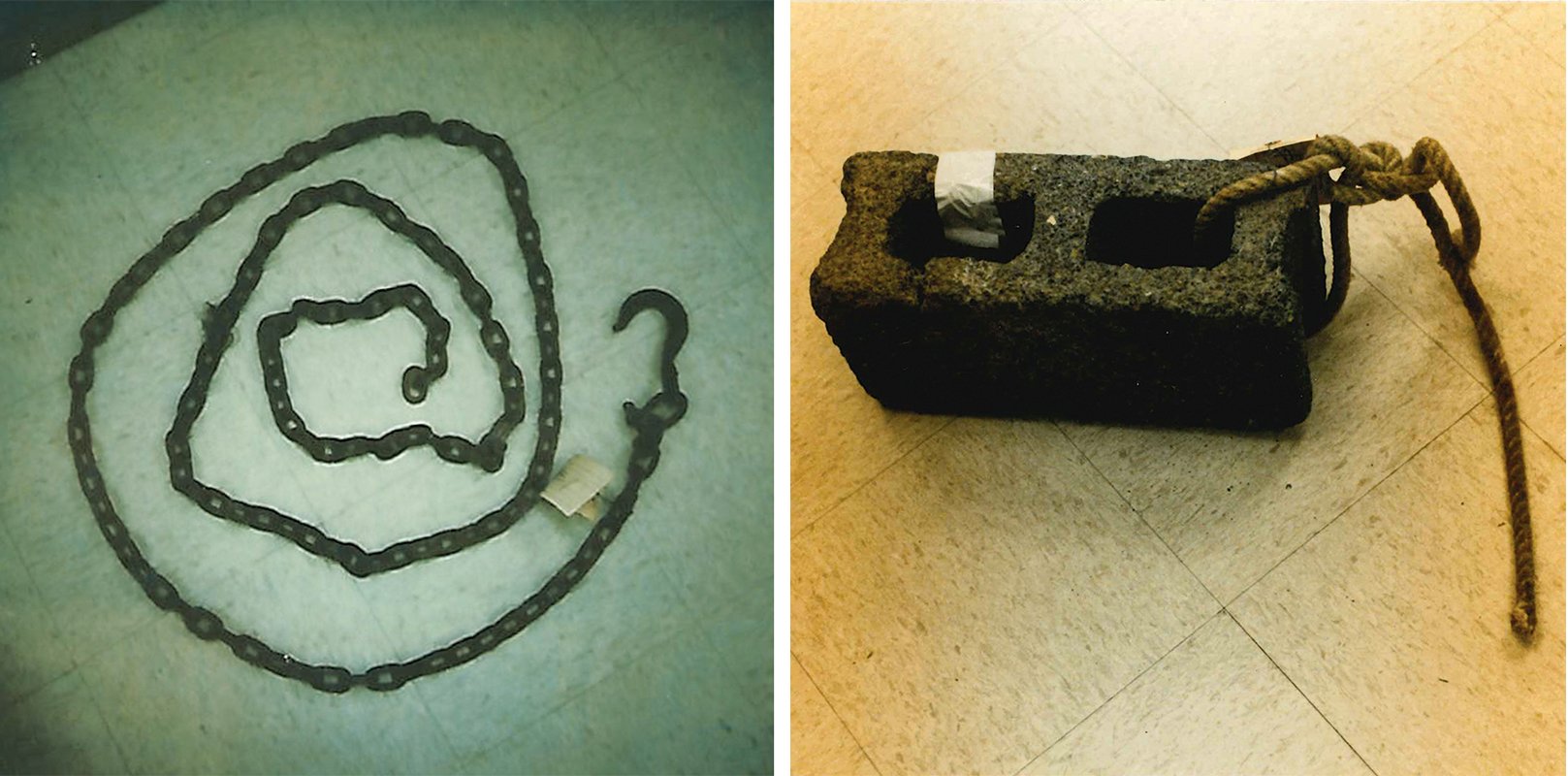

The woman was naked. She had slashes on her back. And whoever had disposed of her had gone to brutal lengths to weigh her down. A rope around her neck was tied to a large cinder block. A heavy chain was secured to the rope, too, its other end wrapped around her right leg. Riley recognized the equipment—you’d find it on the boat of many watermen.

Soon the medical examiner confirmed what everyone already knew. Mary—she was in the water after all.

With a killer on the loose, rumors bloomed like dark bruises. Some people said a Satanic cult had murdered Mary. Others guessed it was a summer vacationer who’d already left town. Either option was easier to stomach than the idea that the murderer was one of their own.

“Everybody was just so scared and, you know, ‘Who’s going to be next?’ ” says Karen Lewis, one of Mary’s best friends. “Of course, that’s what people were thinking—‘It could have been anybody.’ ”

People bought dogs, installed floodlights, added to their gun collections. Some sent their children away to stay with relatives. A psychic came to town to help investigate, and the Bank of Lancaster, Mary’s employer, along with other donors, pooled $20,000 in reward money for information about the crime.

The case was so out of character for Lancaster that multiple law-enforcement agencies teamed up to work it. The FBI dispatched a trio of agents to assist, and local police cracked open their files on potential people of interest. But there was no mistaking who was in charge: David Riley and the Virginia State Police.

Riley prided himself on his command of details—his recall of just the right scrap of evidence when a new turn in a case suddenly made it relevant. “An aggressive agent but very competent,” remembers Louis Sciarrone, one of the FBI agents sent to Lancaster.

Unsurprisingly to anyone who knew the town, one name that Riley and the other law officers heard early and often was Dawson.

Richard and Charles Dawson were well-known hell-raisers. Each had a history of resisting arrest and was considered armed and dangerous by the Lancaster cops, according to a law-enforcement summary of local police files. “I was down there one day and Richard’s on top of the chicken house and the dad’s yelling, ‘Get down from there!’ ” says Keith Hogge, a lifelong Lancaster resident who was then an animal-control officer. “The dad went and got the shotgun. He shot [his son] right in the butt.”

But lately, suspicions about the brothers had become more sinister. At the time of Mary’s disappearance, according to investigative notes from her case, Richard was a suspect in the killing of his wife. (He was never charged in her death.) Charles was on the run after being accused of raping an eight-year-old girl. (He was convicted in 1986.)

Riley went to talk to Richard, but the brother didn’t have anything to offer. He slugged from a can of Old Milwaukee as he told the detective he’d been with his kids the whole night Mary had been taken. As for his brother Charles, he said he hadn’t seen him in weeks.

Another person Riley considered was a waterman named Keith Wilmer. He was the husband of one of Mary’s coworkers, with a record of making obscene phone calls, according to investigative notes. But when he allowed police to search his house, boat, and truck, they didn’t turn up anything useful. Wilmer also took a polygraph. It came back inconclusive.

Riley spoke to Mary’s husband, too. Emerson Harding told him the couple had had some difficulty early in their marriage because of his immaturity—drinking too much, hanging out with the boys. But lately, he said, the relationship had been solid. Riley didn’t consider Harding a suspect anyway. He’d learned early on that Harding had been out to sea, working, on the night in question. When his ship got word Mary was missing, it made an emergency trip back to shore to drop him off.

As Riley tracked down leads, he posted up at the R&K Country Inn, the convenience store where watermen gassed up their boats and cashed their checks. It wasn’t long before he began to zero in on one fisherman in particular. The man was an independent operator that Mary’s husband had singled out, and one who happened to share his first name: Emerson Stevens.

Like his father and brothers, Stevens was a crabber and oysterman—had been since quitting school after the ninth grade. He worked a 32-foot wooden boat named for his wife, the Miss Sandra. People knew him as a typical waterman: simple, liked his Old Milwaukee. “What you saw is what you got,” says Lawrence Taft, owner of the R&K.

Some people said it was a Satanic cult. Others guessed it was a summer vacationer who’d already left town.

Stevens wasn’t a friend of the Hardings’ per se, but he lived nearby and had been to their home. Harding told Riley that the waterman was around during the search parties as well as after Mary’s funeral, and seemed shaky after the service. According to a police report, Harding described him to Riley as a loner and a drinker who talked a lot about women.

He recalled an incident from a year or so before, when he and Stevens both happened to be oystering in a deep spot of the Rappahannock called Mary’s Hole: “You should know all about Mary’s Hole,” Harding remembered Stevens saying, according to the report.

Because Mary was found naked, Riley assumed her killer had sexually assaulted her. Still, he thought, Stevens’s alleged comments didn’t make him a murderer: Men talk like that. But the detective did pick up an interesting tidbit in Harding’s description of Stevens: The waterman drove a white Dodge pickup. And earlier, the police had gotten a call from a tipster who said she’d driven by the Hardings’ the night Mary was abducted and noticed a truck in the driveway. She couldn’t identify the make or model but said it was light-colored.

A few days after Riley’s conversation with Harding, the detective heard from a second witness, Clyde Dunaway, who said he, too, had driven by Mary’s that night and seen a pickup. Dunaway described it as white with a short bed. In fact, Dunaway said he knew exactly whom it belonged to: his cousin Emerson Stevens.

Dunaway wasn’t the only kin turning on the waterman. Down at the boat dock, another cousin, Thomas Stevens, told Riley he had been on the water about 4 am on August 23 and was surprised to see the Miss Sandra heading back toward shore. Stevens, he said, wasn’t typically out so early. Thomas’s wife, Esther, told Riley she’d also noticed something unusual that morning: Stevens’s white Dodge speeding away from the dock at about 6:40.

Then Riley heard a chilling story from a neighbor of Stevens’s named Joyce Williams. A couple years earlier, she told him, she’d been walking from her bathroom to her bedroom, unclothed, when she caught Stevens with his face pressed against her window, staring right at her.

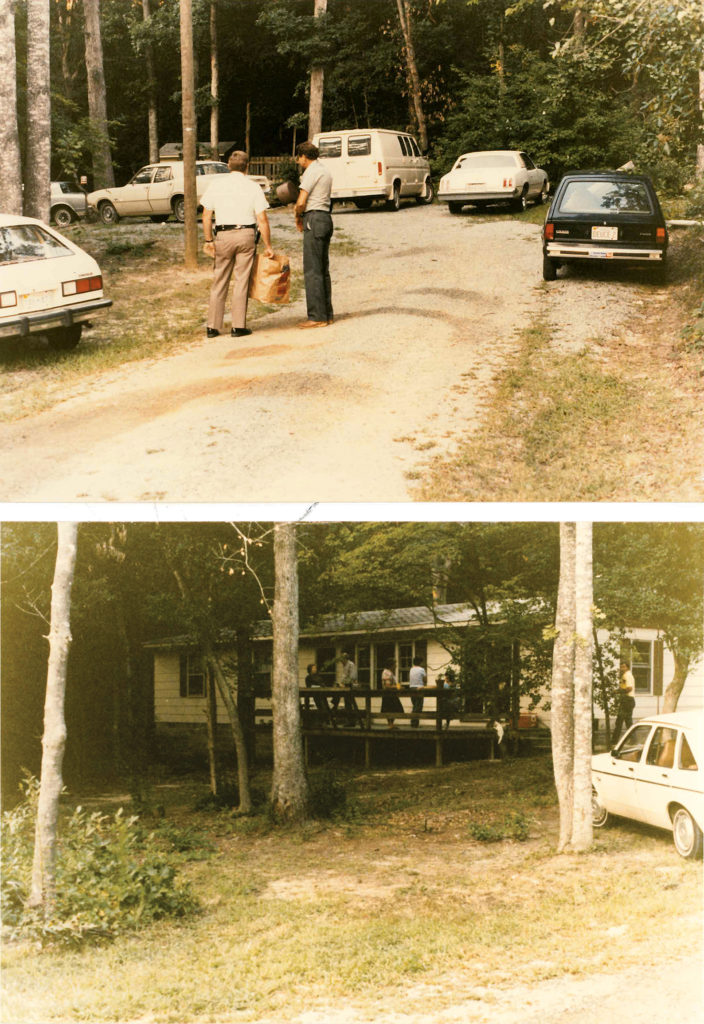

The detective found Stevens at home the next day and told him to follow him to the Harding house. They sat on Mary’s front deck, across the street from the Corrottoman Cemetery, where she’d recently been buried.

Stevens was 32 at the time, with close-set brown eyes, shaggy hair, and a light bulb of a nose. “Tell me why you were parked on the side of the road,” the detective remembers instructing as he pointed out where Stevens’s truck had allegedly been spotted the night Mary died. Stevens insisted he’d been home the whole time. He said that he was at a neighbor’s house with his kids, eating crabs and watching TV, that they went home around 9:30, and that his wife returned from her shift at a retirement home a while later. “Go and check my alibi,” Stevens urged.

Riley wasn’t convinced. He ordered a search of both the truck and Stevens’s boat. After eight hours, a pair of state police officers had evidence to send to the crime lab for analysis: a strand of hair that had been clinging to a plaid shirt inside the pickup.

Back at Mary’s house, where he returned to reexamine the scene, Riley noticed a dogwood tree with scuffing around the trunk, as if someone had climbed it. He scaled it himself and found that it gave him a direct line of sight into Mary’s bedroom—at night, with the lights on, he thought, someone would have a clear view inside.

Within a week, the detective had his suspect at headquarters, hooked up to a polygraph. Stevens blew it. “There’s only two reasons you failed this test,” Riley recalls telling him. “Either because you killed Mary Harding or you’re guilty of something else related to it.”

When Stevens continued to deny any involvement, Riley says he offered him an out—“You were probably there that night doing something innocent”—and suddenly Stevens changed his story. He hadn’t actually gone straight home after the crab dinner at his neighbors’, he said. Rather, he’d taken his kids on a drive to visit his sister. On the way there, they were near Mary’s house, Stevens said, when he pulled over to urinate on the side of the road.

It wasn’t a confession, but it was a huge break. Riley had gotten his suspect to place himself at the scene of the crime.

A week later, one of Stevens’s fishing buddies seemed to fill in another hole in the case. He told the detective that Stevens used to keep a Wildcat Skinner, a type of folding knife, in a leather sheath on his dash. It had a long blade—good for cutting through rope or fishing line—and Stevens’s friend said he hadn’t seen it since Mary’s disappearance. Riley thought he may have finally found the explanation for those slashes in Mary’s back.

That afternoon, he pulled up to Stevens’s parents’ house as his suspect was carrying groceries inside, and cornered him. “Emerson,” he says he asked, “where’s your Wildcat Skinner knife?”

Riley saw Stevens start to tremble. The waterman backed away till he hit the fence, then raised a shaking, pointed finger. “Get outta here!” Riley remembers him yelling.

Before long, the detective got forensics on Stevens to back up his growing suspicions. The hair analysis on the strand from the waterman’s Dodge came back from the state crime lab. It was a match to Mary.

On Halloween, a little more than two months after her death, the Rappahannock Record reported the news from its front page: Emerson Stevens had been arrested for the abduction and murder of Mary Keyser Harding.

At Stevens’s trial the following February, Lancaster County prosecutor C. Jeffers Schmidt Jr. laid out his and Riley’s grisly theory of the case. Stevens, he told the jurors, was a stealthy predator who had stalked Mary for weeks, sneaking into her yard and peeping at her from the perfect hiding spot: the dogwood tree outside her bedroom window.

“When he saw her the night that he killed her—those little blue shorts and that little white T-shirt—that really set him off,” Schmidt said. “She was going through the house. She had Comet in the [sink] and in the toilet, and she was cleaning up. . . . She brought the cat-litter box out. . . . When she got around the corner of her house, right around that corner where this dogwood is, she saw somebody back there. She saw this man back there. Surprise. . . .

“He grabbed her. . . . One of her flip-flops came off over here while she was fighting to get away from him. . . . He throws her in the back of the truck, and what does he do with her? He panicked. I don’t know whether he meant to go over there and kill her, but he meant to go over there and look in her window. You can infer that his motive was to go over there and rape her. . . .

“He had the [rope] . . . . He had the knife . . . . Finally his mind started clicking . . . . He wrapped it around her neck. He said, ‘Well, I know what I can do with her body. I can give her to the crabs . . . .’ He said, ‘Well, if I put the chain on her and if I put the [cinder] block on her, and if I take this knife and I slice her body open to draw the blood and throw her over, there is not going to be anything left in two or three days.’ ”

Lancaster was riveted by the trial. Every day, curious residents streamed through the white-columned entrance of the 1800s courthouse to watch the drama unfold. They watched as Schmidt got the medical examiner to stipulate that a knife like Stevens’s Wildcat Skinner—still nowhere to be found—was capable of making the wounds to Mary’s back. And they watched as he called one of the nation’s top experts in forensic hair analysis to the stand to describe how the strand found in Stevens’s pickup contained “a unique pattern” that matched it to Mary.

Then came all those cousins of the defendant—Thomas and Esther Stevens first, and later Clyde Dunaway testifying he was certain he’d seen Stevens’s truck parked by the Harding house the night Mary died. “I slowed to about 30 or 35 miles an hour,” Dunaway told the jury. “It was just across the road.”

On the third day of the proceeding, jurors got to hear Stevens’s side of the case. Four people who said they’d had dinner with Stevens at his neighbor’s that night took the stand and backed up his alibi. His 11-year-old daughter, Jennifer, who was also there, testified about heading home with him about 9:30 pm, watching a few minutes of TV, and then going to bed around 10 or 10:30, after her father had turned in. Stevens’s wife told the jury he was in bed asleep when she returned from work at five past midnight.

Stevens also took the stand himself and tried to explain away the new story he’d told after failing his polygraph—about taking his kids to his sister’s and stopping to pee near Mary’s. He said he’d made it all up to get Detective Riley off his back. “I was tired,” Stevens said, “and I wanted to go home.”

But in the end, the case was mostly circumstantial, not much of a lock for either side. Indeed, when the jurors returned after seven hours of deliberating, there was no verdict. Instead, they announced, they were hung.

For a fleeting moment, Stevens and his wife allowed themselves to hope the prosecution might drop the case. Before getting entangled in this mess, they’d led unexceptional lives—teenage sweethearts who’d married young and made a modest home on the same dirt road as Stevens’s parents. Stevens, who had no history of violence, not only maintained he wasn’t a murderer or a peeping Tom—he said he hardly even knew Mary. He might recognize her at the grocery store, sure, but he claimed he’d never really talked to her.

“He said, ‘Well, I know what I can do with her body. I can give her to the crabs.'”

It didn’t matter. After the second trial opened on July 8, 1986, Stevens’s own father inadvertently helped the prosecution frame its case against his son. The new testimony centered on the missing knife. During the first trial, Stevens had said he knew what had happened to his Wildcat Skinner: He’d dropped it overboard while fishing. But now his father, Howard, told the jury the story was bogus. Howard said he was the person who’d made the Wildcat Skinner disappear—and that Stevens well knew he’d done it. “I throwed it in the woods,” Howard said. “I got rid of it because he was hassled so bad.”

Stevens was caught. He tried to explain why he’d lied. “Well, I didn’t—I just didn’t want somebody to think I was the one that killed the girl and used that knife,” he stammered when he took the stand.

Schmidt pressed Stevens on all his fabrications. “You admit to us you lied about going up to your sister’s and taking a piss on the side of the road?”

“Yes, I told that,” said Stevens.

“You have a hard time with times, don’t you?” Schmidt asked when Stevens tripped over seemingly simple questions about his alibi.

“Yes, I do. I’m not a smart person,” he said.

This time, when the jurors came back, the courtroom erupted in cheering and wailing. Outside, someone rang the cast-iron bell planted on the lawn, signaling that a verdict had come down. Emerson Stevens, the jury said, was guilty. They recommended to the judge that he go to prison for 164 years.

Stevens and his wife had brought their three kids to court that day, thinking it might help jurors see him as a family man. Instead, they watched police handcuff their dad and march him out of the courtroom. Hearing the verdict, Stevens says, was a shock: “I knew I was innocent of the crime. How could they have convicted me on that little bit of evidence?”

In the fall of 1986, he was sent to the Powhatan prison northwest of Richmond. Alone in his cell, he would turn the second trial over in his mind. His circular bumbling and lies had hurt him, that was true. But as weeks turned to months and then years, he focused again and again on aspects of the case that he thought should have swayed jurors. Such as what happened when a Lancaster resident named Anne Dick took the stand. At the first trial, Dick testified about driving on Route 354 in the predawn hours the morning Mary went missing and seeing Stevens’s Dodge pass without its lights on. She said she couldn’t make out the driver’s face, but whoever it was had on a plaid shirt.

One of the nation’s top experts in hair analysis described how the hair found in Stevens’s truck was a match to Mary.

At the second trial, however, she gave a new version of events. She said she didn’t actually know whose truck she’d seen, and she was certain the driver wasn’t Stevens.

Then why, Stevens’s lawyer asked her, didn’t she tell the first jury that?

“Because Detective Riley told me not to,” Dick replied.

It was an astonishing admission, and for a moment Stevens felt a surge of relief. “I thought they was going to declare another mistrial,” he says. But the proceeding forged ahead.

Another inconsistency between the two trials was more subtle. It involved Belle Isle, the location where Mary’s body surfaced.

Stevens kept his boat a good ten miles downstream from Belle Isle. If he had dumped her all the way up there, it would have meant a long nighttime journey upriver to ditch a body in shallow water along an exposed shoreline, when the wide-open waters of the Chesapeake were just as close. Not only that, but Stevens’s boat wasn’t rigged for the dark. How did that make sense?

During the first trial, Schmidt had called Dr. John Boon, from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, to explain how Stevens could have dumped the body near his dock, only for the Rappahannock’s currents to carry it ten miles upriver—even in its weighted-down state.

But at the second trial, Boon didn’t show up. Instead, his prior testimony was simply read aloud to the jury, and Schmidt never explained why the scientist wasn’t there.

These weren’t just the obsessions of a man languishing in prison. After the trial, Stevens’s lawyer, James Parker, had filed a formal complaint against Riley with the Virginia State Police. “I am solidly of the opinion that [Stevens] was convicted as a result of the unlawful and ethically despicable conduct of Agent Riley in collaboration with Lancaster County Commonwealth’s Attorney C. Jeffers Schmidt Jr.,” Parker wrote in the complaint, adding, “Your investigation should reveal that this case was handled in a sloppy fashion from its inception.”

Parker also asked the court to appoint a special prosecutor to probe possible improprieties in the case. The commonwealth’s attorney from another county was tapped for the job, and his conclusions were devastating. The special prosecutor found that Clyde Dunaway—Stevens’s cousin and the only person who claimed to have seen his truck at Mary’s at the time of her abduction—called in the tip to Riley a full nine days after Mary went missing, and only after news of the reward was published. It turned out the money had come up in one of Dunaway’s first interviews with the detective; from there, Dunaway proceeded to ask four more police officers about it, telling one that he’d contacted an attorney to help him sue for it. Yet at Stevens’s second trial, Dunaway testified under oath that he’d never inquired about the $20,000.

Dunaway, the closest person the state had had to an eyewitness against Stevens, was charged with obstruction of justice. In 1988, he pleaded guilty to the offense.

The revelations were not enough, though, as Parker worked to appeal Stevens’s case. Maybe mistakes got made in a small town eager for closure. But the lawyer failed to persuade the courts to overturn Stevens’s conviction.

After he went to prison, Stevens told Sandra to divorce him. His ordeal had already cost his family so much. The couple had sold their house to cover his legal bills and had uprooted their children to a new school, where they hoped they wouldn’t get bullied so badly. Stevens says he told Sandra, “ ‘You just go ahead with your life and move on.’ ”

At first, Sandra continued to visit him with the children, but eventually she remarried. When the kids got older, they visited Stevens on their own. Then they had children and started bringing them along, too. Sandra and the kids say they never doubted Stevens—that their testimony about being with him that night was the truth. The rest of Lancaster, meanwhile, mainly moved on.

At night, Stevens dreamed of the wide-open Rappahannock. He sketched pictures of boats and water and tuned in to fishing shows on PBS whenever he could. He wrote to his family constantly, sent them cards for every holiday—even the minor ones, like St. Patrick’s Day—and saved all year to mail $100 to each of his three kids for Christmas.

He stayed out of trouble, got his GED, and worked in the prison shop building furniture for motor-vehicle departments, schools, and other state facilities. His good behavior earned him some small comforts, such as a cell without a roommate.

Over the years, he wrote to lawyers around Virginia, asking if they’d look at his case. At one point, he wrote to the governor. He never heard back.

One spring afternoon in 2002, 16 years after his conviction, Stevens was watching the local news when a story about another murder case came on.

He listened as a CBS reporter in Richmond talked about Beverly Monroe, a 65-year-old woman who a decade earlier had been found guilty of killing her boyfriend. The details of Monroe’s case could hardly have been more different from Stevens’s: She was a chemist whose art-collector beau was named Roger de la Burde, a supposed French count who lived on a 220-acre horse-country estate by the James River. Even so, Stevens felt encouraged when the reporter said Monroe had just been released because a federal judge had thrown out her conviction. The broadcast cut to footage of her walking out of jail, smiling widely, her daughter by her side.

A few weeks later, Stevens still hadn’t shaken the image when he got hold of a Richmond Times-Dispatch. He spotted an article about Monroe, and a name in the third paragraph jumped out: David Riley.

“That’s the same rascal that got me,” Stevens says he thought.

Riley had been the lead investigator in Burde’s death in 1992. The medical examiner had initially ruled it a suicide: Burde, whose royal lineage had been called into question and who was under FBI investigation, had been found with his own revolver by his hand. But Riley had become convinced of foul play. He’d learned of a compelling motive, too: Another woman was pregnant with Burde’s child.

Monroe, though, had insisted she knew all about the affair and that she and Burde were working things out. She had a grocery-store receipt that she said proved she’d left Burde’s mansion after dinner on the night he died. Riley, she alleged in court papers, subjected her to lengthy, confusing interrogations, to make her doubt her own memory and convince her of a totally new version of events: “That she must have fallen asleep in the den after she and Burde had dinner and awakened to the sound of Burde shooting himself . . . gone into shock, suppressed any memory of the tragic incident, and then left and gone to the grocery store.”

Monroe had had a climactic confrontation with Riley, one detailed in court papers, in which she alleges the detective told her that if she just admitted to killing Burde, she would only be charged with second-degree murder. When Monroe still refused to confess, Riley reverted to his scenario in which she had simply been asleep in the mansion when Burde shot himself. He wrote it down and asked Monroe to sign it. She did, but only, she alleges, because she was “under extreme duress from Riley’s threats.” The document, which looked like proof Monroe had initially lied about being present at Burde’s death, was critical to the prosecution.

In the Times-Dispatch story that Stevens read in prison, Monroe said Riley had “bombarded” her. To Stevens, her account felt eerily familiar: Riley pressing him over and over again to say he’d been at Mary’s that night, how he’d finally broken down after his polygraph and made up the story about stopping there to pee. “That’s the same way Riley did me,” Stevens says he thought.

“You could tell him something, and he would come back to you and say, ‘I don’t care what you say. It’s like this,’ ” Stevens says of the detective.

“I knew I was innocent. How could they have convicted me on that little bit of evidence?”

Sure enough, when Monroe’s lawyers convinced the federal court to revisit her conviction, the judge found that “substantially tainted evidence and testimony” had been allowed into her trial. The judge stopped short of calling Riley’s methods unlawful but nonetheless had scathing words for the police work: “The Court finds that the tactics engaged in by Riley were deceitful, manipulative, and inappropriate.”

During all his years in prison, Stevens had tried to stay positive—ending Christmas letters to his kids with “Maybe next year, we’ll be together” and, when they visited, making plans for “when I get out of here.”

For so long, it was mostly just talk. Now that he knew about Monroe, though, everything felt different.

Back to Top

Part Two

One autumn morning in 2009, 23 years after Emerson Stevens went to prison for murdering Mary Keyser Harding, a lawyer named Deirdre Enright answered her phone, eager to learn more about him.

Enright—then 49, with red hair, freckles, and a weakness for four-letter words—had spent most of her career defending death-row inmates. She was now the founder of the Innocence Project at the University of Virginia School of Law, working to overturn wrongful convictions. The case of Beverly Monroe—the horse-country woman falsely convicted of killing her phony-French-count boyfriend—was well known in Enright’s crowd. She’d heard that Monroe’s lawyer, Stephen Northup, had been working with Stevens. The fact that both investigations had been led by the same detective—David Riley of the Virginia State Police—piqued her interest.

On the phone with Northup, Enright asked him why she should take Stevens’s case. “He said, ‘I want to give him hope,’ ” Enright says of the conversation. “I was like, ‘Uh, I don’t do the hope business. If it’s a dead end, I’m not taking it.’ ”

Enright had hundreds of other potential clients to consider, but she let Northup explain. He was a partner at the national law firm Troutman Sanders who had taken Stevens’s case pro bono six years earlier, after Stevens read about Monroe and wrote to him. With the help of a private investigator, Northup had slowly chipped away at the matter, but he hadn’t found enough to take a shot at freeing Stevens. Enright thought there was a chance an attorney in her position could make better progress. “Law-firm lawyers,” she says, “can’t go out and beat the bushes themselves.”

She says Northup told her how the FBI had sent agents to Lancaster back in 1985 to work alongside the local authorities but that the feds’ report was mysteriously missing. Northup also told her about Anne Dick, the Lancaster woman who initially testified that she’d seen Stevens’s truck the morning Mary was discovered missing but then changed her story at the second trial, saying she was certain Stevens was not the person she’d seen. When asked why she didn’t tell the first jury that, Dick said, “Because Detective Riley told me not to.” A detective with a solid case, Enright thought, doesn’t waste time pressuring people to manipulate the facts.

Enright went digging through Northup’s files on Stevens and found an old affidavit from a merchant named Ray Reynolds, who ran the crabhouse where Stevens used to sell his catch: He said he’d initially told Riley that Stevens had arrived at an unusual time that morning—but later checked his records and realized he’d confused it with another day. Reynolds said Riley “told me to go ahead and testify and to stick with my original statement.” Reynolds refused and was never called to the stand. Were there others, Enright wondered, waiting to tell their own stories about Riley?

Enright also learned about Stevens’s cousin Clyde Dunaway, the star prosecution witness who’d been the only person claiming to have seen Stevens’s truck at Mary’s at the time of her murder. On the stand, Dunaway had testified he’d never inquired about the $20,000 reward for information about the crime. But after the guilty verdict, an investigation determined that Dunaway had, in fact, repeatedly asked about the money. For his false testimony, Dunaway pleaded guilty in 1988 to obstructing justice in Stevens’s case. “It was another huge red flag,” Enright says.

And there was that missing FBI report that Northup had mentioned. Reading the trial transcripts, Enright noticed that Stevens’s trial lawyer had pressed the judge for access to it—but been denied after the prosecutor objected. Had the feds reached a different conclusion than Riley? What might she find in that report if she could get her hands on it?

Enright tracked down Stevens’s trial lawyer, by then sick with a brain tumor, to get his take. She says he told her that Stevens had been railroaded: “He’s like, ‘This was a disaster.’ ”

So in June 2010, Enright went to meet Stevens. He told her about the prison shop where he worked on furniture, and he explained how to build a chair. She stayed until the guards shut down visiting hours. “The whole ‘look him in the eye and know he’s innocent’—all those things to me are distractions,” says Enright. Still, she had to admit she liked him.

It was the beginning, Enright knew, of an arduous process—piecing together new theories of a decades-old crime and trying to show that investigators had gotten it wrong could prove impossible. Even so, she felt there was enough evidence to justify her own investigation into what happened on August 22, 1985.

One of the first matters Enright wanted to look into was Mary’s husband, Emerson Harding. She’d noticed that during Stevens’s trial, his lawyer had asked questions that seemed designed to make the jury wonder if the husband had played some role in the murder. By the time of the second trial, Harding had been seen around town with other women. He had collected more than $80,000 in life-insurance money, and he was driving a new sports car. To Stevens’s trial lawyer, Harding didn’t necessarily look like a grieving spouse.

Enright went to see Harding’s second wife, a woman named Margie Hogge. The two had wed after Mary’s death, then divorced in 1999. In the dimly lit living room that she once shared with Harding, Hogge gave Enright a harrowing account of her former marriage. According to a sworn affidavit, she said Harding “could become quickly and easily enraged and volatile when he was drinking.” She described an incident when he came home drunk in the summer of 1989: “He was punching me on the side of my head . . . . I thought he was going to kill me.”

She continued: “One time, he got so mad at our [nine-year-old] daughter, Riva, he picked her up by her throat and banged her head against her closet door again and again—eight or nine times—until he was done with her.” (Hogge never filed police reports documenting the alleged abuse, and Harding was never charged. Harding could not be reached directly; through Mary’s sister, he declined to comment.)

After leaving Hogge’s house, Enright felt troubled that investigators didn’t seem to have scrutinized Harding. His activities in the days before Mary’s murder especially bothered her. Harding was typically out to sea all week, but at Stevens’s trials, he testified that he had made an unusual, midweek trip home on Wednesday night, the evening before Mary was killed. He said he was back on his ship the following night, but Enright hadn’t found anything to convince her of his story. None of Harding’s shipmates had taken the stand, and she didn’t have a manifest from the boat. She wondered if Harding had ever gotten back on it at all.

Not everyone in Lancaster was willing to help Enright. When she knocked on the door of a retired sheriff’s deputy, she says, he berated her and cornered her on his porch. “There was a time when that would have menaced me,” says Enright. “Now I’m old and I don’t give a rat’s ass.”

C. Jeffers Schmidt Jr., the Commonwealth’s Attorney who had prosecuted Stevens and was still in office nearly three decades later, was more polite but no more forthcoming. Enright says he declined to let her crack open his files on the case (which Schmidt denies). The old FBI report was a sticking point, too. The court record indicated it was under seal at the courthouse, yet Enright couldn’t get anyone to produce it.

So she drilled down on the key piece of evidence she did have access to: the hair found in Stevens’s truck, which supposedly came from Mary. It had been the only physical evidence connecting Stevens to the crime. But forensic science had advanced dramatically since the trial. Microscopic hair comparison—the technique used to match the hair to Mary—had come under scrutiny and, in fact, would soon be proven unreliable. (By 2015, 74 people would be exonerated by DNA in cases in which microscopic hair comparison had been a factor.)

Enright wanted to put the strand through DNA testing—a process that hadn’t existed in 1985. It would require a judge’s permission, which Schmidt might object to. So her team began making a case, finding old jurors who said they would support the testing. One said she didn’t believe she could have convicted Stevens without the hair.

By the time of Stevens’s second trial, Mary’s widower had been seen around town with other women.

As it turned out, though, Schmidt never got the chance to weigh in on the test. While Enright and her then law partner, Matthew Engle, were working up their pleading, Lancaster voters were preparing to go to the polls—and when Election Day came, Schmidt lost his eighth race for Commonwealth’s Attorney in a stunning upset. All of a sudden, Lancaster had a prosecutor with no professional investment in the case of Mary Harding.

Schmidt’s defeat set off a dizzying sequence of events that rocked the small town. Within weeks of the election, the incoming Commonwealth’s Attorney was accusing Schmidt of purging files and of forcing his staff to sign nondisclosure agreements. The saga went on for months, with Virginia’s attorney general eventually having Schmidt arrested for allegedly destroying public records. (The charge was later dismissed.)

The upheaval was a boon for the Innocence Project: Schmidt’s successor gave Enright and her staff access to the old files on Emerson Stevens.

One day in 2013, after Schmidt left office, Engle was in town leafing through the paperwork when he made a startling find: a letter to Schmidt from the marine scientist John Boon. Boon was the tidal expert who had testified at Stevens’s first trial about how Mary’s body could float ten miles upstream, but—for reasons that were never disclosed—he hadn’t appeared at the second trial, the one in which Stevens was convicted. In that proceeding, a transcript of his prior testimony had instead been read aloud. The letter seemed to explain why Boon hadn’t shown up himself. “Was this testimony truly of use to you or the court?” Boon had written to Schmidt before the start of the second trial. “In a brief ‘interview’ before my last appearance at the Circuit Court, your associate, Lt. Riley, applied what may be the correct term to my testimony in this case. He called it ‘eyewash.’ ”

Engle looked up the word. It meant “nonsense,” according to the dictionary. Or, as Engle puts it, “bullshit.”

When Enright saw the letter, she was floored. The lawyers say they thought its meaning was obvious: Riley had never believed in one of the key parts of his case against Stevens.

Yet it appeared that Schmidt had not disclosed any of this to Stevens’s trial lawyer. Says Engle: “That was absolutely clear evidence of prosecutorial misconduct.”

If Enright and her team were going to help Stevens, they would have to do it without an assist from modern science. In November 2013, nearly a year after they sent the hair to a lab in Lorton for DNA analysis, Engle opened an e-mail with the results. “It was crushing,” he says.

The lab had been unable to reach a conclusion about whom the hair had come from, meaning it could have been Mary’s or Stevens’s or anybody’s. “I really thought at that point that we had lost our opportunity to win the case,” says Engle.

The pace slowed for a while as Enright and her team juggled other clients, but in the fall of 2015, Enright got a new reason to feel hopeful. Sheriff Ronnie Crockett—who’d won his first election two years before Mary’s murder—was retiring his badge and starting a second act as a real-estate agent. For the first time since Mary died, in other words, neither of Lancaster’s top law-enforcement officials had played a role in putting Stevens behind bars. “People got less and less protective of the case,” says Enright.

By this point, she’d been grinding away for five years: She had Anne Dick and Ray Reynolds, both of whom alleged Riley had asked them to stick with stories they said weren’t true. She had Clyde Dunaway, the witness who’d pleaded guilty to obstructing justice. She had the “eyewash” letter. Now she decided to turn her attention to another major piece of evidence she’d had her doubts about: the Wildcat Skinner, the knife Riley had used to connect Stevens to the gashes on Mary’s back.

Those cuts had always seemed strange to Enright. They were almost uniform in length. And because the killer had strangled Mary, why bother with a knife at all? Enright didn’t buy the gory explanation proffered in court—in which the prosecutor suggested the killer had sliced open his victim to entice crabs to eat away the evidence.

Enright called Marcella Fierro, the medical examiner who’d performed Mary’s autopsy. Fierro had testified that Stevens’s Wildcat Skinner could have made the cuts. Enright wanted to know if she would stand by her original assessment.

The hair found in Stevens’s truck was the only physical evidence against him, but the science had come under scrutiny.

Fierro, who had risen to chief medical examiner for the entire Commonwealth before retiring, agreed to take another look. She reviewed her old reports and numerous photos of Mary floating in the Rappahannock. She e-mailed a listserv of other coroners to test out a different theory, asking if anyone had photos that might back it up. The responses filled her in-box.

By the time she got on a second call with Enright, Fierro had reached a new conclusion. The cuts on Mary, she said, most likely came from a boat propeller—postmortem. Not from the Wildcat Skinner. Not from any knife at all.

In March 2016, Enright was back in Lancaster, looking onto a vast soybean field from Lawrence Taft’s living room. She’d shown up unannounced, but when she explained why she was there, Taft and his wife were happy to invite her in.

Taft had owned the R&K store, the waterman hangout where Riley had poked around during his investigation. Enright had seen an old report that indicated Taft had been interviewed by Riley back in 1985. Plus, she knew Mary had stopped at the R&K the night she was killed. Enright thought Taft might remember something useful.

It turned out he did. One day, Taft said, Riley showed up at the store “looking serious,” wanting to discuss Emerson Stevens. The waterman was a frequent customer, dropping in several times a day to gas up his boat or buy beer. Taft told Riley he didn’t think Stevens was capable of harming anyone. Then, he said, Riley changed tactics. As Taft detailed in a sworn statement for Enright, “Detective Riley tried repeatedly to get me to say that Emerson Stevens woke me up in the middle of the night that Mary Harding disappeared so that he could buy five gallons of gas. Detective Riley was extremely aggressive and pushy, insisting that I agree with his story even though it was not true. I was never woken up in the middle of the night by Emerson Stevens ever, for any reason.”

Taft told Enright he had made it plain to Riley “that I was not someone who could be bullied into lying. I remember this very clearly,” Taft said, “because I was shocked that a law-enforcement officer would behave this way.”

Enright found Taft’s matter-of-fact account totally believable. “I loved him,” she says, “because he was just like, ‘Riley was a bully. His thing just didn’t work on me.’ ”

With Taft’s story in hand, Enright and her new law partner, Jennifer Givens, felt they finally had enough to file a petition asking the court to throw out Stevens’s conviction—even without the still-missing FBI report.

Then, the very day after submitting their pleading, Enright’s cell phone rang. It was a deputy for Patrick McCranie, Lancaster’s new sheriff. Almost immediately after he’d taken office, Enright had dropped in to see McCranie. “She wanted to know if we knew where the [FBI] file was,” McCranie says. “I was like, ‘I have no clue.’ Heck, I don’t even know where to file things at.”

Now Enright could hardly believe what McCranie’s deputy was calling to tell her: They’d found a box of evidence in storage. The FBI report was inside. Would she like to come see it?

When Enright and a couple of her students arrived at the courthouse, they could immediately tell that the new sheriff’s decision to hand over the documents was controversial. “Literally, we were escorted, from the minute we got out of the car, by two guards,” remembers Enright. “They were saying, ‘There’s some people here who are pretty angry about this.’ ”

As she’d hoped, the box was full of revelations.

First, a joint filing from the FBI, Riley, and the Lancaster sheriff divulged a new theory about where the authorities believed Mary’s body had been ditched—and it was nowhere near Stevens’s dock, a direct contradiction to the narrative floated in court. The officers estimated that Mary’s killer had left her “within 500 to 600 yards of where [she] was eventually located.” Second, the documents showed that two of the men Riley and the FBI were initially interested in each kept boats near where the remains were found.

“I was not someone who could be bullied into lying. I was shocked that a law-enforcement officer would behave this way.”

One of them, Keith Wilmer, was the husband of one of Mary’s colleagues at the Bank of Lancaster, the waterman whose polygraph had been inconclusive. Investigators noted in the files that they had heard concerning stories about him from two women in town. A bank employee said Wilmer had made obscene telephone calls and aggressive, sexual advances toward her and once followed her home after dark, according to the FBI report. A woman who worked as a dispatcher for the sheriff’s department told police that Wilmer had also called her, tried unsuccessfully to disguise his voice, and told her he wanted to have sex with her in the woods. (Other than to emphasize that he was cleared in Mary’s case, Wilmer declined to comment.)

The other, Richard Dawson, had had his share of run-ins with the law. His own wife had died just weeks before Mary, and the FBI’s paperwork stated he had been staying with a friend in a trailer up the street from the Harding house: The two men “partied” the week of the abduction near the victim’s residence, it said, and Dawson “was seen riding with a second unknown person in a light colored truck in the vicinity of the victim’s residence” the night Mary was killed.

Dawson had also had troubles at Mary’s bank. Investigators noted that he’d gotten into an altercation with one of Mary’s colleagues over his wife’s account. Mary and her coworker had shared a cubicle that had Mary’s nameplate on the front. The colleague had told the FBI she worried Dawson may have mistaken her for Mary during their argument.

The materials continued: “Witnesses have stated that Dawson has been ‘hunting for women’ for sex after his wife’s death.”

There was more. In an interview Riley did with Mary’s husband, Harding mentioned that Dawson’s late wife had responded to an ad Mary had placed seeking a babysitter. She had pleaded for the job, but Mary had turned her down because of the family’s reputation.

Despite all this information, there’s no indication Riley ever gave Dawson a polygraph. (Dawson died in 2009.)

When Enright finished examining the write-ups on the men, she could see nothing to explain why they hadn’t been pursued harder. Both had stronger connections to Mary, and both kept boats near where her body was found. Yet Riley had zeroed in on her client. Why?

“They were troublesome, and Emerson is easy,” Enright concludes. “Emerson’s going to be pushed around and be terrified.”

The box also contained records on the Lancaster resident Enright had always wanted to know more about: Emerson Harding.

In all the years Enright had pored over Stevens’s case, she’d never been sure how closely Riley had looked at Mary’s husband. She’d also never seen a ship manifest that she felt proved Harding was out to sea on the night of the murder.

In the box, Enright found the captain’s daily fishing report as well as an attendance record from Harding’s ship. According to the documents, the vessel was anchored in the Chesapeake for the night by 8 pm on August 22. Mary was still alive then—she had spoken to her sister on the phone just after 9 pm. The materials listed Harding as present on the boat. They were never shown in court, but Riley must have come across them during his investigation and perhaps used them to help rule out Harding as a suspect. After all, they backed up his alibi.

Other paperwork in the box, however, raised a new, thornier set of questions.

Riley’s reports showed he had interviewed Harding three times. It was during the third conversation, a week after Mary turned up dead, that Harding suggested Riley check out Emerson Stevens. This was the conversation in which Harding described Stevens’s crude comment about the area of the Rappahannock called Mary’s Hole, when Stevens allegedly said Harding “should know all about” the place. Harding repeated the story on the stand at both trials.

Yet as Enright read Riley’s reports, she noticed a discrepancy: Under oath at the trials, Harding said the conversation had happened two Sundays before Mary was killed. But according to Riley’s paperwork, Harding said he’d heard Stevens make the comment a year or so before.

There was another discrepancy. On the witness stand, Harding said that when his ship had made that unusual midweek stop home Wednesday night, the night before Mary’s murder, he’d gone out to feed the dog and “heard something on the side of the house in the woods . . . . I walked in the woods and shined the flashlight. It was something moving around.”

The comments were teed up by Schmidt, the prosecutor, seemingly to insinuate that Mary’s stalker might have been outside that night, too. Riley’s summaries of his conversations with Harding, however, didn’t mention anything about the strange noise. That was odd, Enright thought. Why would Mary’s husband leave such a crucial detail out of his conversations with police?

To Enright, it looked as if Harding had embellished significant parts of his story for the jury. As far as she could tell, the prosecution hadn’t disclosed either of these discrepancies to Stevens’s defense—a clear violation, in her opinion.

To Enright, the most concerning document that related to Mary’s husband was a letter she had never seen. It was written by Schmidt before the second trial. In it, he raised concerns about Emerson Harding’s activities after Mary’s death—anticipating how Stevens’s trial lawyer would try to cast doubt about Harding in the minds of the jury. “Emerson Harding may be an issue,” the prosecutor wrote. “There is the question of $81,000.00 [in] life insurance proceeds. There is the question of a fancy new sports car. There is a question of dating Cindy Hayden and Jerry Weber’s daughter.” The person to whom Schmidt was pointing out these concerns? David Riley.

Enright thought the letter showed that Riley and Schmidt had doubted Mary’s husband after all and that they should have looked into him further.

Armed with the new information, Enright and Givens filed an amended petition laying out how they believed Stevens had been wronged. Schmidt, they said, had knowingly presented false testimony and repeatedly failed to turn over crucial information to the defense. (Schmidt’s response to me: “Inaccurate.”)

“While any one of these pieces of evidence could have altered the outcome, there can be no doubt that, when considered cumulatively, this undisclosed evidence would have resulted in a not-guilty verdict,” Enright and Givens wrote in their filing. “Mr. Stevens’s conviction,” the lawyers asserted, “was engineered by an irresponsible prosecutor and an unscrupulous detective anxious to close a high profile case that shocked a small Virginia community.”

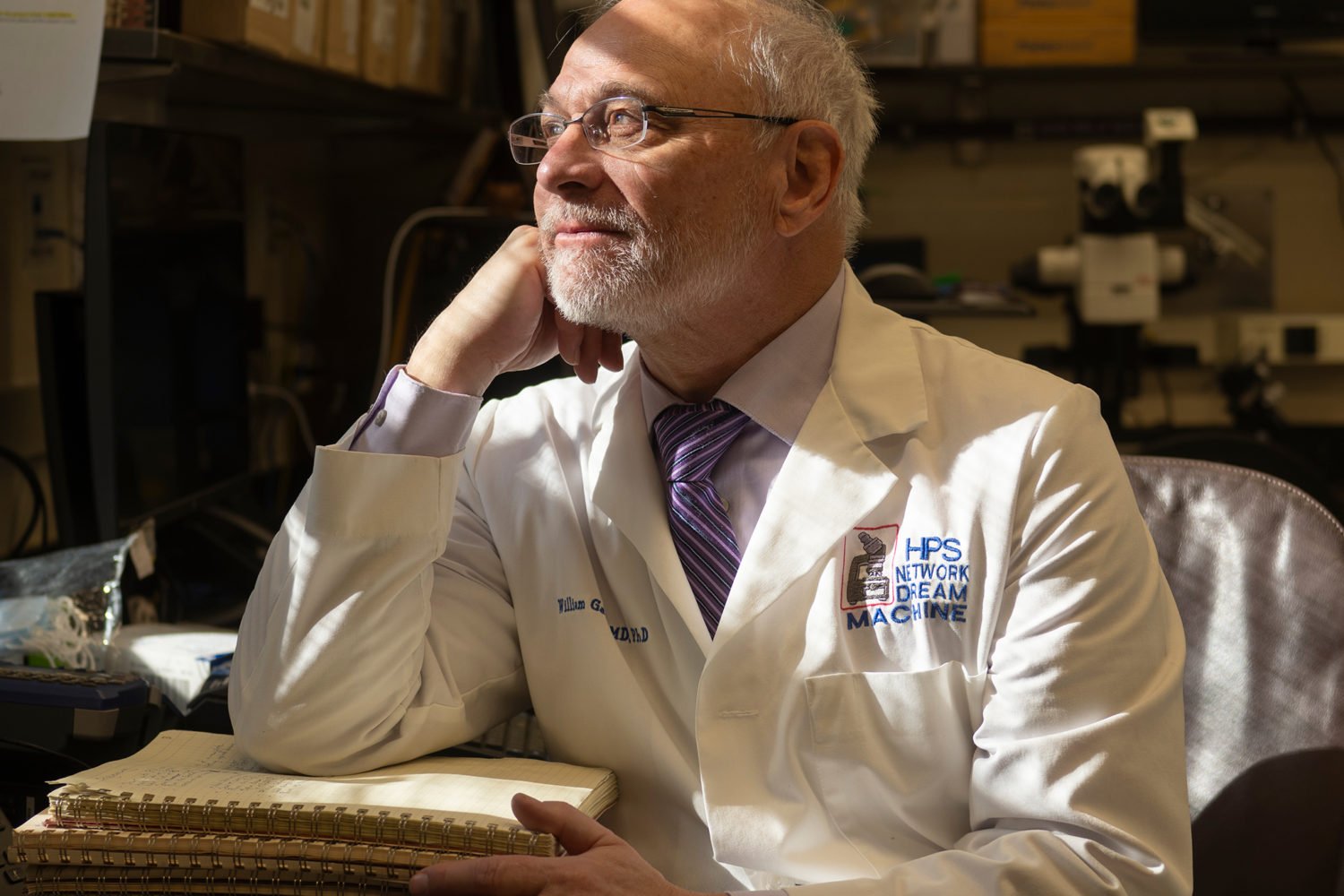

I ring David Riley’s doorbell on a sweltering August afternoon. The 70-year-old who answers is plump around the middle, with a wispy, white comb-over and very striking eyes—as crystal-blue as a Siberian husky’s.

At first, he says he doesn’t want to talk, but eventually he invites me into his Northern Neck home, leans back in his leather recliner, and unspools the story of the case in intricate detail.

Before I can ask why he homed in on Emerson Stevens, he starts in on the dogwood tree outside the Harding house—the tree where the prosecutor said Stevens had been hiding and spying on Mary the night of her murder. Riley describes how he decided to climb it after noticing scuff marks on the trunk and hearing Stevens’s neighbor accuse the waterman of peeping on her. “Even old and fat like I am now,” Riley tells me, “I could still climb it.”

“We were escorted from the car by two guards. They were saying, ‘There’s some people here who are pretty angry about this.'”

Then he recounts his first interview with Stevens, when he took Stevens to Mary’s front deck. “I said, ‘Tell me why you were parked on the side of the road.’ ” When Stevens denied having been there, Riley tells me, he offered a suggestion. “I said, ‘You probably had to relieve yourself’—I didn’t use those words, because men don’t use those words—but I said, ‘You probably stopped to relieve yourself on the side of the road.’ He didn’t take the bait.”

This was new to me. The case documents and trial transcripts—even Stevens himself—had made it sound as if Stevens came up with that story on his own after failing his polygraph. But here was Riley saying he’d fed it to him weeks earlier.

After Stevens blew the lie detector, Riley continues, “I said, ‘There’s only two reasons you failed this test: either because you killed Mary Harding or you’re guilty of something else related to it.’ I said, ‘You were probably there that night doing something innocent’—and he bit.”

Out came the story about stopping to pee, when Stevens finally put himself at the scene of the crime.

“He already had that in his mind as an out,” says Riley. “I used the same tactics in the Emerson Stevens case as I did with Beverly Monroe. . . . If you can’t get a direct confession, you just try to get them to talk. They’ll say things against their own interest as a way to wiggle out. The whole thing is to keep people talking and steer them in the direction you want them to go.”

I ask Riley about the witnesses who allege he pressured them.

People such as Ray Reynolds, the crabhouse manager who said Riley had gotten upset with him when Reynolds realized he had confused crucial dates, and thus couldn’t testify that Stevens had shown up late with his catch on the day after the murder. “[Riley] was pissed,” Reynolds had told me. “Oh, my God, yeah. He said, ‘Man, we gotta stick with the story. Just tell ’em what you told me before.’ ”

Riley tells me he remembers getting frustrated with Reynolds, but he denies telling him to stick to his original story. (Under cross-examination on the witness stand, Riley had confirmed that he saw Reynolds’s crabhouse log and that it showed that Stevens had followed his normal routine the day after the murder.) Riley says Anne Dick—the woman who testified at the second trial that Riley had instructed her to say she saw Stevens’s truck—changed her story as retaliation against town law enforcement in a squabble over her dog. (Schmidt had offered the same reasoning at trial.)

As for pressuring R&K owner Lawrence Taft to say Stevens wanted to buy gas in the middle of the night, Riley says: “That, my dear, is an absolute lie.”

I ask Riley why Stevens, who had no history of violence, stood out to him above other men in town, such as Richard Dawson.

“The famous Dawson brothers. They were nasty people, but they weren’t rapists. . . . This is not the Dawson M.O.,” says Riley. I was surprised by his assessment, considering Richard’s brother Charles was convicted of raping an eight-year-old girl and, in their petition to free Stevens, the Innocence Project had referenced an old rape allegation against Richard. But Riley went on. “I have literally been in a frozen pigsty on their property wrestling a Dawson brother,” he says. The man—Riley can’t remember which Dawson—had abducted a woman. “I was there to get her.”

“But you don’t think he raped her?” I ask, astonished.

“I’m sure he had sex with her,” Riley says, “but I’m not sure he raped her.”

The logic is baffling. He has just described going out to the Dawsons’ to rescue a woman but then dismissed the possibility that Richard Dawson could have abducted and raped Mary. Meanwhile, he pursued Stevens, who had no known violent M.O. Why dismiss Dawson but not Stevens? Riley was ready with his answer, his theory of the entire sordid case.

“Stevens didn’t have a violent past, but he had a sexual interest in women beyond the normal,” he tells me. “An escalating peeping Tom.”

Riley stands by his investigation. “There’s no such thing as a perfect case,” he says. “There’s cases I’d do differently. I can’t think of anything I would have done differently in this.”

Riley knows about the Innocence Project’s inquiry. He sounds embittered about the way their findings portray him.

“I’m always the villain,” he says.

Enright’s first try at getting Stevens’s conviction overturned didn’t work.

In its motion to dismiss the Innocence Project’s petition, the Virginia attorney general’s office had picked apart Stevens’s claims as meritless, untimely, or both. The state asserted that Stevens couldn’t claim that Schmidt had committed prosecutorial misconduct by withholding the FBI report during the July 1986 trial, because the judge at that time had ruled that Schmidt wasn’t obligated to turn it over.

When it was put into context, the state argued that John Boon’s “eyewash” letter was “a request from a ‘professional’ who preferred not to sacrifice four business days but was nevertheless willing to testify” at the second trial.

The state wrote that Stevens’s trial lawyer had already raised the discrepancies in Emerson Harding’s testimony during his failed appeal of Stevens’s guilty verdict decades ago. Thus, they were now an invalid claim.

As for Richard Dawson and Keith Wilmer, the state asserted the men had been ruled out by the police’s investigation.

On December 1, 2017, Lancaster County circuit judge Michael McKinney sided with the Commonwealth.

Enright and Givens appealed in Virginia’s Supreme Court, which in November 2018 denied them a hearing. With the state courts exhausted, their next step is to file Stevens’s case in federal court.

The one person who sits in the gallery at every hearing is Beverly Monroe. She and Stevens became pen pals after her lawyer took him on as a client. She began mailing him photos of the Chesapeake Bay and scenes she captured on walks, such as a shot she took of a bald eagle. “One of the ways of surviving is to get your mind out of that pit—to project your mind outside,” she explains.

Monroe is 81 now and lives in Williamsburg. From time to time, she speaks with law students and others about her ordeal. She married her neighbor, a 94-year-old man from across the street. Last fall, they drove four hours to watch a ten-minute courtroom oral argument on Stevens’s behalf. Monroe does it, she says, because someone must bear witness to the way the justice system is treating Stevens: “It’s important in a way you can’t describe—that simply to be there is better than not to be there.”

But even as his case plods through the court system, Stevens has already gotten something of a happy ending. When he came up for parole in the spring of 2017, a slew of people showed up to advocate for his release. Enright and Givens were there and laid out the evidence they’d gathered. Stephen Northup, Monroe’s lawyer, emphasized Stevens’s flawless record in prison. Carrie Odom, Stevens’s daughter, remembers how their 45 minutes of allotted time ballooned to two hours. “We told them how our dad got ripped from us and everything fell apart,” she says.

The parole board let Stevens walk out of Greensville Correctional on May 19, 2017—31 years after he went to prison. He’s not allowed to return to Lancaster, where some of his siblings still reside and his parents are buried.

Which may be just as well for Mary’s family and many in town. McCranie, the sheriff, says he was hounded by Emerson Harding for handing over the FBI report to Enright—something McCranie views as the neutral obligation of a public official. Taft, of the old R&K store, says he’s nervous about even talking to a reporter. “We live in a very small community,” he tells me. “I can’t go running my mouth about this.”

In truth, opinions are all over the place. Mary’s older sister, Helen Webb, says she’s certain the right man went to jail. “All they’re doing is opening up old wounds over and over and over again,” she says of the Innocence Project. She laughs at Enright’s suggestion in court papers that her brother-in-law should have been a suspect. Harding and Mary, she says, had been planning their future and saving to buy a house. “My sisters and myself, we’re not shrinking violets. We’re strong, opinionated women, and Emerson was okay with that,” says Webb. “He is not abusive. I have known him since he was in high school. He and his family, that’s just not who they are.”

Mary’s brother John Keyser studied criminology because of his sister’s murder. He, too, says he believes Mary was happily married. He wishes the Innocence Project’s investigation wasn’t still dragging on but says he was fine with them revisiting her case: “I would hate to find out that we did not have the right person. I’m 90 percent sure that it’s [Stevens]. Or 95 percent sure. But you just—you can never know. You can’t be 100 percent.”

“There’s no such thing as a perfect case. There’s cases I’d do differently. I can’t think of anything I would have done differently in this.”

Mary’s best friend from high school, Marjorie Holt, meanwhile, says she never got any comfort from Stevens’s conviction: “I felt like they pinned it on someone just to make it go away. From day one, I didn’t feel he was the right guy.”

She’d rather talk about Mary, though, than why the case went awry. “She had a spark—a spirit. She just was one of those people who could talk to anybody,” Holt says. “I was shy and kind of bullied. She definitely saved me in high school.” Before graduation, Mary gave her a gift. Feeling the weight of it, Holt was embarrassed, thinking there was no way Mary could afford whatever was in the box. It turned out Mary had cleaned up some old bricks from her yard. “She says, ‘These are four bricks to help you build the rest of your life.’ ” Holt chokes up. “She was a deep soul.”

For Stevens, now 65, rebuilding his own life has involved a person he never expected: Sandra, the ex-wife who divorced him while he was in prison but who never doubted his innocence.

After falling out of touch for decades, she and Stevens reconnected in 2015 while grieving the sudden death of their eldest daughter, Jennifer. “She always wanted us to be back together,” says Sandra, whose second marriage didn’t work out. “She told me that all the time.” Sandra invited Stevens to live with her in her house near the North Carolina border. “I felt like I was getting to know him all over again,” she says. “We’re older now. We’re not kids.” They started as roommates but are officially back together.

Stevens is polite and plainspoken, his once shaggy brown hair neatly combed and graying. At his and Sandra’s house far into the country, he says that even though he’s out of prison, it’s still important to keep fighting to clear his name: “I know I’m innocent of the crime, and I don’t want that on me. I want to be able to go where I want to go—I can’t even go to see my mother and father’s graves.”

Yet this place feels like home now, too. He introduces me to Candy, the hound mix he and Sandra adopted. She sleeps in bed with them every night. He tells me about the job he got with a local company that makes tents for weddings and other outdoor celebrations. His boss, Kreig O’Bryant, says Stevens is his most dependable employee: “We gave him a key two years ago.”

Out front, Stevens shows me the purple rosebush he and Sandra planted in memory of their daughter Jennifer, and the broken-down speedboat that a friend gave him. It’s nothing like the 32-foot Miss Sandra, but it may yet get him back on the water. He has already reupholstered the seats with leftover vinyl from the tent shop, and he’s saving for a new motor.

“Hopefully,” he says, “one of these days I can take it fishing.”

This article appears in the June and July 2019 issues of Washingtonian.