In 2006, Greg Whiteley had recently wrapped his second documentary about high school debaters when a brief item in a newspaper caught his eye. The story said that the then-governor of Massachusetts, Mitt Romney, would be gathering with his family over the Christmas holidays to discuss whether he should run for President.

“There was something about that that sounded like the beginning of a great documentary,” says Whiteley. Seven years later, the result is Mitt, Whiteley’s intimate and surprising portrait of Romney and his family over the course of two successive presidential campaigns. The documentary had its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival last weekend with Mitt and Ann Romney in attendance, and gets its general release via Netflix on Friday.

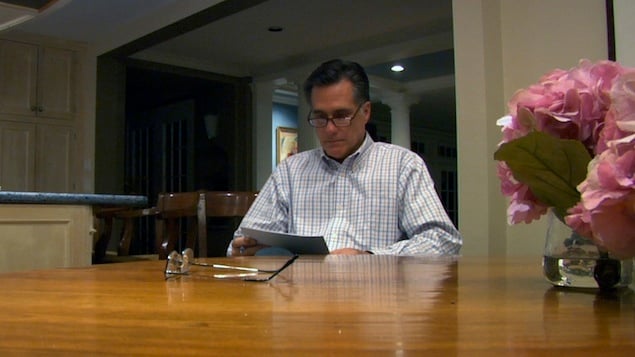

Most of the buzz surrounding the movie has focused on how different Whiteley’s subject is from the robotic, permatanned, clunky caricature of 2008 and 2012. Surrounded by his family and removed, for the most part, from his campaign operatives (who declined to be filmed), Romney romps in the snow with his grandchildren wearing gloves stuck together with duct tape, tells a stylist to be careful not to “break” his hair, and obsessively gathers up trash in his hotel room. He defends the George Clooney comedy O Brother, Where Art Thou? to his sons as “the best movie ever,” and mocks his own status in the media as “the Flipping Mormon.”

What’s really remarkable about Mitt, however, is the access Whiteley was granted, and the extent to which the film focuses on the family first and the campaign second. When Romney twice declined Whiteley’s request to film the family’s 2006 meeting, it was Ann who told the documentarian, via her son Tagg, that she was “intrigued” and who let him know that if he showed up at the Romney’s Utah house on Christmas Eve he might be invited in. “I grabbed my family, we drove to Park City, and on Christmas Eve I showed up at the address Tagg had given me at the Romneys’ old house in Deer Valley,” Whiteley says. “I knocked on the door, and Mitt opened it, sort of rolled his eyes, and let me come in.”

Without much discussion, Whiteley says, the family let him start filming, and he continued for the next six years, capturing Romney’s unsuccessful run for the Republican nomination in 2008 and his campaign for the presidency against Barack Obama in 2012. The agreement he had with the Romneys was that no footage would be released until the Governor was done either running for or being President, and he’s bemused by stories questioning whether the film could have helped Romney as a candidate had it been released earlier.

“If you see the movie, you know that by 2012 I haven’t filmed the end yet,” he says. “Plus I think people look at Mitt differently after the election. My intent in making the movie wasn’t to persuade people that he was a good guy, or that he should be President, and I think if I had released any footage prior to the election that would have been called into question.”

Mitt, for the most part, touches lightly on 2012 events that were covered obsessively at the time, such as the “47 percent” video that cast Romney as a candidate for the rich, or the endless debates he participated in during the leadup to the Republican primaries. Romney’s infamous offer of a $10,000 bet with Texas Governor Rick Perry is left out, as is the Romney campaign’s vetting of vice presidential candidates. Paul Ryan appears only once, on election day, to shake hands and exchange platitudes with the man who might be his new boss. They are friendly enough, but appear to be more like amiable strangers than close partners.

Instead, Whiteley focuses on Romney’s wife and five extremely photogenic sons, most of whom are remarkably unfiltered. In one scene, the family are discussing the controversy over a car elevator the Romneys want to install in one of their houses when Josh Romney blurts out that his father should say, “It’s for my wife’s MS, you A-hole.” In an earlier scene filmed in 2008 after the Florida primary results have come in, Tagg Romney tells the camera, “We basically just lost the presidency, and nobody’s that upset.”

It’s this ambivalence toward actually being President that comes across as one of the most revealing parts of Mitt. “I think I need to write myself some notes on why I would not want to do this again,” says Ann in 2008. “You’d be bald in about a month,” says Josh at the family’s 2006 discussion summit. “I think the con would be that you’d have to actually be President,” says Josh’s wife, Jen. “Don’t do it,” says Tagg. “But if you don’t win, we’ll still love you. The country will think of you as a laughingstock and we’ll know the truth, and that’s okay.”

“I think if you’re going to expend the kind of resources necessary to make a real run for the presidency, you have to feel called to do it,” says Whiteley. He recalls asking Romney about his motivations for running, and the candidate responding with a story about his father, George Romney, who also ran for President. “Mitt talked to him about [losing], and he said, ‘Dad, was it hard?’ And the way Mitt describes, George just dismissed it and said, ‘No, I have a great life. I offered my services to the public and the public didn’t want them, and that’s fine. I get to go back to my great life.’ And I think Mitt feels the same way.”

Mitt is available on Netflix Friday. For more information, visit the movie’s website.