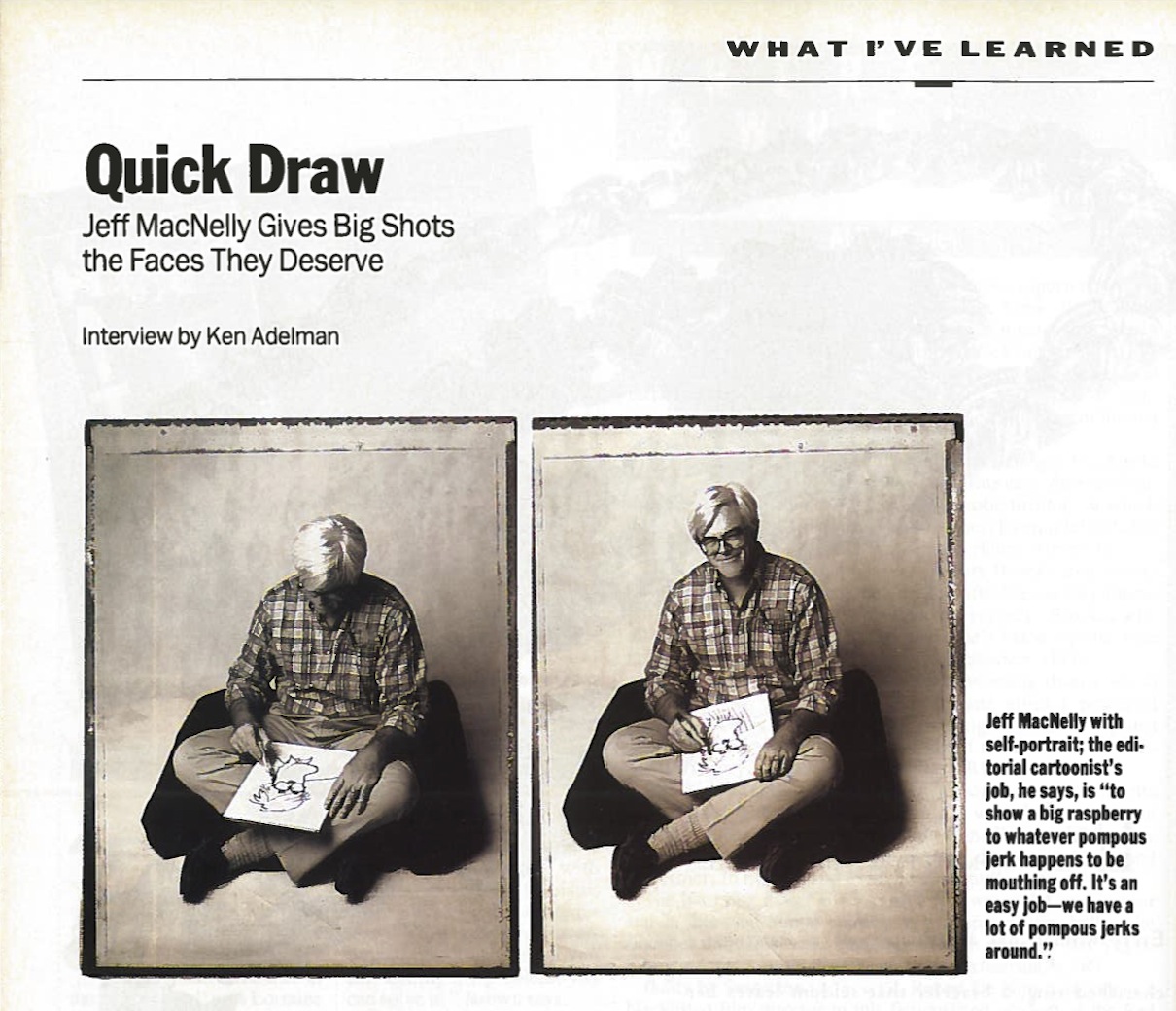

Jeff MacNelly, a political cartoonist who earned three Pulitzer Prizes for his editorial cartoons and widespread affection for his syndicated strip “Shoe,” died 15 years ago this week. For our May 1991 issue, he sat down with Washingtonian national editor Ken Adelman to talk about politics and the process of cartooning. The editorial cartoonist’s job, he said, is “to show a big raspberry to whatever pompous jerk happens to be mouthing off. It’s an easy job–we have a lot of pompous jerks around.”

Not many people know Jeff MacNelly, but many people react to his opinions.

MacNelly’s editorial cartoons, produced in the Washington bureau of the Chicago Tribune, appear several times a week in 400 newspapers–and have earned him three Pulitzer Prizes in twenty years.

MacNelly, 43, grew up on Long Island–his influences were Herblock and Bill Mauldin–and attended the University of North Carolina. With a portfolio of work from the campus paper and a Chapel Hill weekly, he got his first job with a daily newspaper in 1970, at the Richmond News Leader.

Within two years he had received his first Pulitzer–the others came in 1978 and 1985–and was recognized by his colleagues as one of the top pen-and-ink men in the business.

In 1978 MacNelly launched a comic strip, Shoe, populated by a covey of feathered journalists in a treetop. Their wry patter now entertains readers in more than 1,000 newspapers. Twice he has won the Reuben, highest honor of the National Cartoonists Society.

MacNelly moved to the Chicago Tribune in 1982, and to its Washington bureau several years later–to be closer to the “gag writers” in government who keep providing him with raw material, he explains. He’s married and lives on a Virginia mountaintop in a small frame house he designed himself.

In his small office on L Street, Northwest, jammed with old drawings, clippings, newspapers, posters, and assorted memorabilia, Jeff MacNelly talked about what he’s learned–and produced some sketches to make his points.

Last century, Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall said, “I don’t mind the editorials, but stop those damn pictures!” He was talking about the editorial cartoons. What’s so powerful about them?

Editorial pages all say, “Well, the other guy has a point, too. It remains to be seen how this will come out. We certainly hope it comes out fine, blah, blah.”

Cartoonists don’t go that way. Our job is to stick out our tongues, to show a big raspberry to whatever pompous jerk happens to be mouthing off. It’s an easy job–we have a lot of pompous jerks around.

And unlike my reporter colleagues, we get to break all the rules. We get to misquote, to slander, all that stuff. And just maybe, when the smoke clears, we come closer to the truth than they do.

The best cartoons have no words at all–just the image pops out.

Have you done some like that?

I’ll draw a president as a fish or something, or Saddam Hussein as a snake. I don’t have to embellish it with words.

How do you come up with the image?

Free association. I let my mind go loose. I’m reading a magazine and I’ll think, “Gosh, George Bush and Saddam Hussein are like the San Francisco 49ers and something else.” I’ve used a lot of sports imagery over the years.

What I’m looking for is metaphors, something that readers identify with. I superimpose some politician or world figure on a familiar metaphor.

Do ideas spring to you at a certain time? Reading? Walking? Taking a shower?

No. I wish they did.

My father was very methodical about life. He’d always ask me, “Now, what’s your system? What’s your schedule like?” I have no big system, no rigid schedule. When he would ask, “How do you do this? Give it to me step by step,” I’d try to convince him that there were no step-by-steps.

The best thing for my creative process is a deadline. My deadline is when Federal Express closes. Unfortunately, they’re open until 8:45 at night.

When I was younger, I’d grab the newspaper, read the three top stories, and rush to do a cartoon on one of them. Most of the time they’d be on topics I had no idea about, like economics.

Now I back away from what’s running in the newspaper, what the latest press conference is about, and do it on what’s really on my mind. All the Gorbachev stories, for example–to me, the guy’s really in trouble.

You brag how you’re not restricted like most journalists. But aren’t there some boundaries for cartoonists?

I hope not. That’d be messy. But I do have a bad-taste-ometer that goes off in my head sometimes. “Gee, I don’t think I’m going to draw the president naked today,” it tells me when I’m tempted. And there are general boundaries; I don’t mess much with other people’s religions.

Every so often I’ll do a cartoon in bad taste. The editor will see this and say something, and I’ll agree, and it won’t run. Years ago, when Nixon was president, I did a simple drawing of him as a bird with a big grin, and at the bottom of the cage was a newspaper labeled “The press.” That one raised some questions. But editors never tell me what to draw. There are some rules I apply, but not many.

You didn’t seem to hold back when drawing President Carter.

My images of Carter changed over time. When he became president, he was always smiling, had a lot of teeth. Everybody liked that. My cartoons said that the new president is a confident, happy guy.

That he’ll do okay….

Sure. He’s got some good ideas, will put them forth, and we’re wishing him good luck. I was living in Richmond then, and I was tickled by the notion that a Southerner had finally gotten to the White House.

But when he insisted on calling himself Jimmy, it started going downhill for me. So before long, Jimmy Carter started to shrink. I’d draw him smaller and put a few freckles on. As the hostage crisis consumed his last year in office, he seemed completely taken over by events. He became tinier and tinier. He lost his grin. His ears flopped down, and his collar got bigger. His neck got real skinny. He turned into a little kid toward the end.

And how did Ronald Reagan change during his time in office?

Reagan rode into town like the sheriff. So early on I drew him as a cowboy. He had this great hat–he’s a very good-looking fellow–and he seemed so young in those early days.

He had an agenda, and I was behind him. That was hard for me, because I hate to do cheerleading cartoons. I’ve been screaming for somebody like Reagan for fifteen years, and suddenly he gets elected. That’s great, but what do I do? I can’t go around saying, “Gee, isn’t the president doing a great job?” That’s not what a political cartoonist does. So I had my problems with Reagan early on.

It’s better to get somebody who you don’t like in the White House?

Absolutely. My biggest problem as a political cartoonist is how to choose between two guys when I go into a voting booth. One guy’s going to be good for the country. The other guy’s going to be good for my business. They’re never the same guy.

Which one do you vote for?

Ugh. I’ve got to tell you–I hold my nose and vote for my country. I know it’s stupid, but….

Anyway, Reagan was the Marlboro man, the guy with new ideas riding into town, cleaning out the bad guys. I basically bought the whole routine.

So you were a cheerleader?

I was. That’s why Reagan didn’t show up often in my cartoons. He wasn’t goofing up, so I couldn’t draw him much. Toward the end of his administration, though, a goofiness did take over, a charming kind of goofiness. When he was in my cartoons after he made a mistake or something, he would get out of these terrible situations by saying, “Oh, sorry about that.”

You did a cartoon comparing him to Houdini.

Yeah. Houdini spends all this time and effort getting out of the trunk–breaking all the chains and everything–while Reagan’s just standing there in the next trunk saying, “Gee, all I did was smile a lot and shake hands, and everything seemed to melt away.”

Toward the end I had fun drawing him as a grandfather figure–a really great guy who was really neat to see but was constantly losing the car keys.

And his ears got bigger. That’s the great thing about human beings–their cartilage keeps growing. The rest of the body falls apart, but ears and noses keep growing. So Reagan’s ears got bigger–the aging process is great for cartoonists. And his eyes began to have a startled look, and his chin changed. So there’s a little benign confusion here, an amiable smile but a bit out of it.

Presidents are your bread and butter, aren’t they?

They’re the symbol of the administration. To show whatever happens in government, I use the president’s face or symbol or something. He’s the guy.

Who else is good for you?

House Speaker Tom Foley. He had the potential to become a Senator Snort type–a little overweight, a close cousin to Tip O’Neill. Then he did this SlimFast thing and lost all that weight….

Which ruined your day.

Well, I feared he was going to get better looking, younger looking, a lot healthier. Actually, he’s now a lot funnier looking, which is great. Foley’s got all kinds of angles he didn’t have before. His ears stick out. His jaw goes one way and his chin another. He’ll be a great character for me.

You also like escapades–Watergate, Iran-contra–and Washington frolics, don’t you?

Yes, I love ’em. Still, I have to step back from some stories and ask if the folks out in Poughkeepsie really care.

But odd episodes, like cakes and Bibles to the Ayatollah….

Those are always wonderful. They are the results of those gag writers in government, who come up with things I could never make up. Reality can be more ridiculous than anything cartoonists invent. At best we’re only a half-hour ahead of the zaniness in real life.

What episode was the most fun?

Watergate. Everybody across America knew about it, since everyone was watching it on TV. I didn’t have to label the different characters. The president’s appointments secretary was a household word.

Nowadays, when things are going right, no big episode stands out. When things are going well, people aren’t paying much attention to Washington. Baghdad, maybe, but not Washington. Every once in a while, you need a total government goof-up.

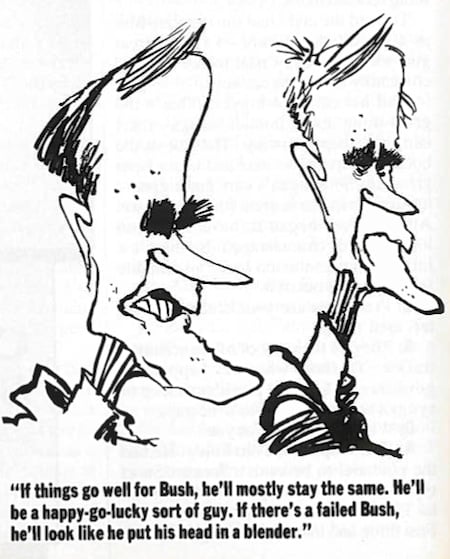

What does George Bush look like?

He’s a basic WASP. He looks like he’s from Connecticut. He looks like me, with all his features jammed into one tiny area in his big head. He’s got a big forehead, a jaw sticking out, and a lot of angles to him. One of his eyes is down and the other’s way up there.

His eyes are not even?

No, they’re in separate counties. They look like they belong to two different people.

When he smiles, half his face does one thing and the other half something else. He’s got a great neck, but he looks like he’s wearing somebody else’s suit–either that or a suit from fifteen years ago. It’s always sticking up in the back, and it’s wrinkled.

There’s a certain sloppiness.

Yes, and thank God. A lot of us can identify with sloppiness. That’s endearing to people, as are his awkward hand gestures. We identify with that. People naturally like the guy.

You talked about Carter and Reagan being transformed in looks while in the White House. How is Bush going to look when his presidency ends?

Depends. If things go well, he’ll mostly stay the same. He’ll be a happy-go-lucky sort of guy.

And if there’s a failed Bush?

He’ll look like he put his head in a blender. I’d draw him as shell-shocked, haggard, forlorn, without that patented smile on. With more of a grimace–the upper lip sagging….

Do you have to see someone a lot to draw him, or can you do it from photos?

For years I’d surround myself with photos of the guy, do sketches, and try to figure out how his face works. Then I learned that the best way to draw is to throw all that out and just let your mind take over. Your brain will filter out all the extraneous stuff and will pick out two or three things to emphasize.

How helpful is it to see somebody in person?

Very. How people hold their body has a lot to do with how they look. For instance, Richard Nixon is one of the most recognizable caricatures–I can draw him with three squiggles–but what really makes Nixon are those high shoulders–and I didn’t discover this until I actually saw him. You don’t notice the shoulders on TV or behind a desk. But when you see him walk through a room, you say, “Hey, he looks like Harvey from sixth grade!”

When someone you’re drawing looks like somebody you know, that makes it easier to put the caricature together.

Are there other presidents you wish were around to cartoon?

Lyndon Johnson–I would have enjoyed messing with him.

Because of the ears?

Because of everything. He was a larger-than-life character. Everyone says, “It must have been great to draw Nixon.” Okay, but he was kind of a boring guy–gets up in the morning, puts on a white shirt and a tie, goes to work. Johnson was holding animals up by the ears, showing people his scars, having barbecues–the whole Texas thing. I would’ve loved to have been in on it. I’d have been slamming him most of the time, so it would have been fun.

How would he have looked to you?

First are those all-conference ears. And he kept changing his glasses every few weeks. That was nice. He had a great nose, one of those Texas mouths, and little snake eyes. Tiny eyeball holes. Johnson was always trying to look like FDR but coming off like a riverboat gambler.

Who do you hope rises to national prominence? Who would be good for your business?

Nowadays all these politicians depend on television to get elected. So they all look like game-show hosts. It’s hideous to stroll around Capitol Hill and see so many blow-dried, eighty-dollar haircuts.

One guy with real potential is Newt Gingrich. He’s got great hair. He’s animated, and you know where he stands. I like politicians like that.

Compromisers are no good? George Mitchell?

He’s terrible. If he didn’t wear glasses, his whole face would disappear down his shirt.

Dick Gephardt’s even worse, because he’s got the Jerry Ford problem. When Ford became president, nobody could identify his photo, much less a cartoon of him, so I couldn’t take much liberty with him. And Gephardt is so blond, but I’m drawing with India ink. I need more of a Greek–more eyebrows, big eyelashes, something.

Who do you hope becomes president so you can draw him for years?

Good for the country would be a Colin Powell or Dick Cheney. But they’re good-looking guys, so they’d be terrible for me. Among the Democrats, nobody would be good. You could use Sam Nunn’s speeches for crowd control. He never changes his expression. Nunn would be okay for the country, but for me, the only thing great about him is that he has no chin.

How about First Ladies–Barbara Bush, Nancy Reagan?

I’ve done Nancy a couple of times, but not Barbara Bush, unless in some big Inaugural scene.

Why not?

It’s not their fault they’re there. The guy got elected.

I liked doing Golda Meir and Maggie Thatcher, though. Thatcher had this classic bird face–sometimes a hawk, but often a chickadee. I did a lot with Thatcher and her purse, beating up on some big guy.

How about new guys in town, like Paul Wellstone from Minnesota?

He’s going to be great for me. He’s a throwback–a ’60s activist, kind of. Very animated. Not afraid to show you who he is. A little Art Garfunkel going for him in the hair, the sincere eyes, the open mouth. And he’s a little guy. I enjoy drawing little guys.

What’s the most critical part of a cartoon? Drawing, idea, layout?

The idea, for sure. You can be the world’s most marvelous artist, but if you don’t have a half-decent idea, nothing will work. You can’t disguise a terrible idea. Some cartoonists who can’t draw well come up with great ideas, and they do well. That’s what moves people–the image, the idea. The drawing is mostly the means to that.

When do you scratch around for ideas?

All the time. I’ll start sketching on the back of a message slip just to get the mechanics going.

People call me with ideas–they have to get them off their chest–and they’ll say, “I’ve got this great idea. There’s George Bush firing a machine gun with the bullets being Democrats, and little Democrats rigged up in this belt,” and on and on. Soon they’re describing a Belgian tapestry. They don’t understand that the whole drawing has to fit into a tiny space, with viewers able to recognize the guys and ideas instantaneously. Simplify, simplify.

So the critical moment in your business is that instant of creativity, not those hours of drawing.

It’s funny–people won’t come in here when I’m drawing. They think I have to be on the planet Mongo to draw. But when I’m staring out the window or sitting and scratching my feet, trying to get an idea, they think, “Hey, I’ll come in and talk to this guy who’s doing nothing.” That’s when I’m doing the toughest part of my job–trying to put ideas together and come up with an image.

What’s the advantage of living in Washington?

It’s a nice place. The disadvantage is that you’re too close to things, surrounded by people who take it all so seriously. You could get swept into the Washington stuff. Then you go an hour out of town and you realize that people are thinking about other stuff.

I’ve got an audience that seems to be listening every so often. I’m able to get somebody to say, “Hey, he’s got a point there,” or, “I never thought of it that way.” Occasionally I even get threats, which shows that somebody somewhere is listening.

That’s what cartoonists do best. We cut through the verbiage and the PR and the television drivel and get right to the gut of the matter. That’s what makes a half-decent cartoon.