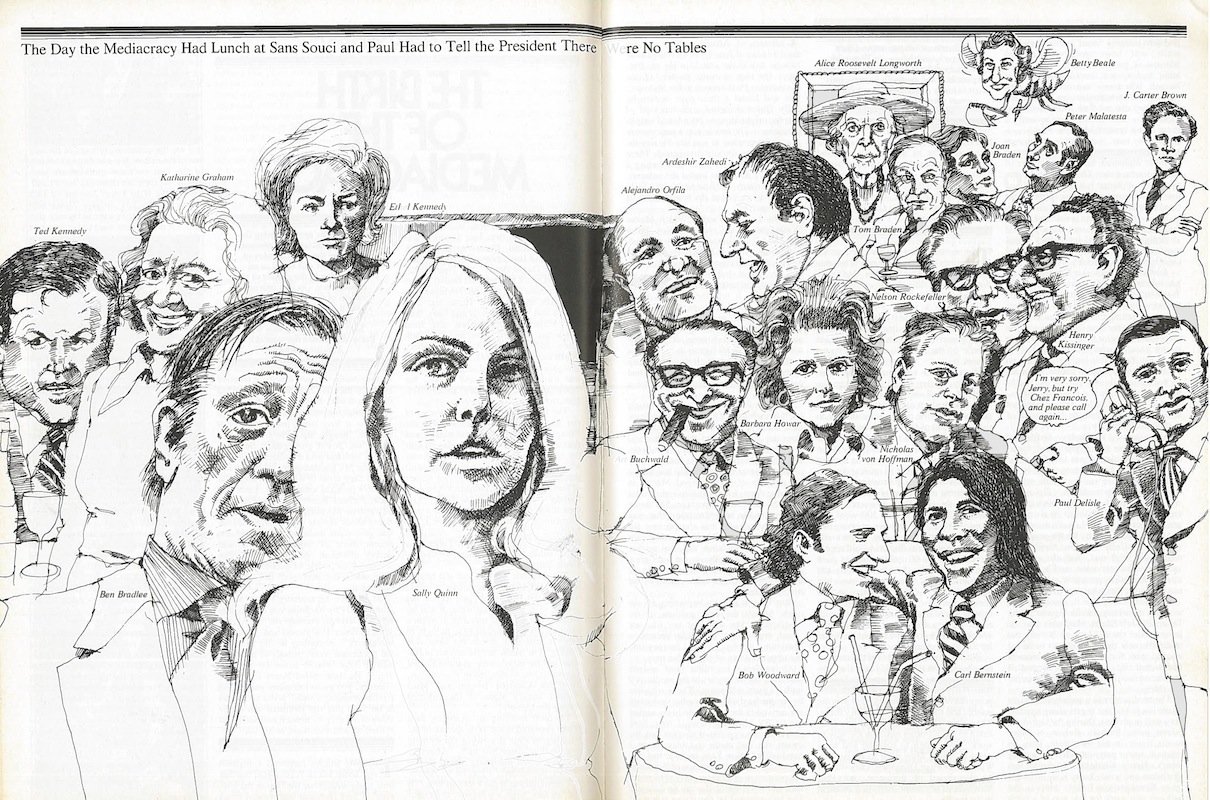

For our April 1975 issue, contributing editor Laurence Leamer charted the death of Washington’s Old Society and the rise of a new aristocracy–a “mediacracy” in which the media was at the center of the city’s social scene and people wanted “to be Woodward or Bernstein, not Paul Newman.” If fewer people now want to be Mark Leibovich than those who aspired to be Bob Woodward, Leamer’s criticisms of the intertwining of journalists and the people they report on still hold up 40 years later. Leamer has since written more than a dozen books, including a trilogy on the Kennedy family.

They sat together that warm January evening in three tiny auditoriums at the Cerberus theater. Eric Sevareid was there and Carl Bernstein and Frank Church and Jack Javits and Candice Bergen and David Broder and Daniel Ellsberg and Mark Hatfield and Daniel Schorr and Richard Reeves and Nicholas von Hoffman and Seymour Hersh and Don Riegle and Walter Pincus and Gary Hart and Father Robert Drinan and John Brademas and Les Aspin and Elizabeth Drew and Claiborne Pell and Timothy Wirth and Mike Nichols. They chatted in low voices and nodded to acquaintances and waited for Hearts and Minds, the controversial documentary about Vietnam, to begin.

The film opened with idyllic scenes of the Vietnamese countryside and with the lilting sounds of Vietnamese music, and then suddenly plunged the audience into the endless horror that is the war. Scene after scene passed by–vignettes with amputees, a napalmed child, two scenesof football games in small-town America, footage of Hollywood war films. And then it was over, with scenes from a pro-Vietnamese parade in New York City. Marines. Crowds holding Americanflags. Boy Scouts. Firemen. Police. An aging baton twirler. A man dressed as Uncle Sam.

The audience shuffled out and headed for the Port o’ Georgetown for a party, where ladies in long dresses passed out goblets of white and red wine. It was an evening when a good time had to mean a bad time. No one would have thought to dance to the rock music the band was playing. The media people and the politicians and the others were as sophisticated a group as one would find in Washington. They left Candice Bergen and Mike Nichols largely alone as they chatted among themselves.

The next morning an article by Jean White appeared in the Style section of the Washington Post describing the evening as a ritual of shame and guilt, “a harrowing, almost self-punishing experience for anyone passionately opposed to America’s participation in the Vietnam War.” It had, in fact, been a complex, contradictory evening. Walter Pincus, executive editor of the New Republic, left thinking the film a true work of art, but Bernard Gwertzman remembered his three years in Moscow as New York Times correspondent and thought the film’s techniques much like Soviet propaganda. Seymour Hersh, who had won a Pulitzer for uncovering the My Lai massacre, left the theater with a deep sense of discomfort about the movie’s political assumptions. Later that night Richard Reeves of New York and Marguerite Michaels of Time argued for hours about Hearts and Minds. Reeves had seen some faults but he thought it a decent piece of work. Michaels was deeply offended; she thought the film slandered the people of middle America, particularly the people of her Midwest homeland.

The following morning’s Post had a commentary by Nicholas von Hoffman in which he said the evening was “not one of your swishier Hollywood and Washington affairs.” According to von Hoffman the politicians were “mostly of the ratty, sincere type who’ll never be fashionable.” He then chided Henry Kissinger: “Henry, you go to too many parties and too few amputee wards.” It did not matter in the least that von Hoffman was something of a partygoer himself and had never visited an amputee ward in his life.

• • •

The two articles furthered a mythology about life in Washington that has little to do with either the film or the evening. If von Hoffman had wanted to sit among unswanky journalists and “ratty”politicians he could have attended the film during its regular run, but this evening he was there among his peers in the mediacracy, Washington’s new elite. As for Ms. White’s piece, it created a common vision for the evening that simply did not exist.

The mediacracy is a public aristocracy of people important in the media and people who gain power through the media. It consists of the names and faces that are the common currency of the city and of the nation. It is not simply a society of the best or most professional journalists,for there are those like Jerry Landauer of the Wall Street Journal or Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times who simply lack the style ever to become part of it. Or do not ever want to become part of it.

The mediacracy could develop only now that journalism has become an extraordinary force in our lives, no longer a fourth and lower estate. For example, when the New York Times ran a continuing series about the CIA’s two decades of illegal activities, President Ford had nochoice but to appoint a committee to investigate the charges. As Walter Pincus wrote in the New Republic, “like it or not” the editors of the Times and the Post are “participants. Their front-page story selections set an agenda for government.”

Out of this increased power has come a terrible self-consciousness. Among its artifactsare Tom Wicker’s Facing the Lions, a Washington novel whose protagonist is a journalist (journalists before were narrative devices in political novels); Elizabeth Drew’s Watergate diary in the New Yorker, equating one journalist’s life and impressions with the most important Washington story in decades; Dan Rather’s verbal jousting with former PresidentNixon; All the President’s Men, not a political book at all but a detective story elevating Woodward and Bernstein to the first order of our culture heroes; and All the President’s Men, the forthcomingmovie starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, which almost certainly will become a media phenomenon, helping to establish even more the primacy of the Washington mediacracy.

Politicians also are part of the mediacracy. “Ted Kennedy” is an institution of more than 100 people adept at creating media experiences. Les Aspin largely eschews the traditional role of the legislator to garner publicity through press releases. Among the new House members there aremany who live almost completely within the mediacracy. Toby Moffit of Connecticut, for instance, has hired an investigative reporter to build stepping stones for Moffit up to the top of the mediacracy.

Henry Kissinger is a great prince of the mediacracy. He realized early in Washington that when a political figure is both “hard” news and “soft” news, both coverages tend to be less critical. Indeed, for many months Kissinger was an unsullied hero to many “hard” news reporters, while “soft” news reporters were turning him into a great swinging bachelor; the latter was no less implausible than the former. When new tenants moved into Kissinger’s townhouse on Waterside Drive they did not find what one would expect in a sex symbol’s house–only a great many centerfolds from Playboy, a great many hats, and a full-length mirror in the bedroom.

Some diplomats have become part of the mediacracy too. The traditional function of the diplomat has steadily declined over the past century as mass communications have increased, and most diplomats in Washington perform a role not unlike that of airline stewardesses. Their jobs are absurdly romanticized while they spend most of their time serving meals and cleaning up minor messes.

Ambassador Ardeshir Zahedi of Iran has become one of the main fixtures of Washington social reporting. There he is, throwing another terrific bash at the embassy and getting this big spread in Style. There he is in the Star listed as one of the three great bachelor hosts of the capital. It is not exactly what Talleyrand had in mind. But Zahedi has legitimized Iran, an oil-rich, Middle Eastern nation, as an accepted, indeed desired part of the Washington scene. That is a political achievement of no small order, and it could not have been done within the framework of traditional diplomacy.

Ambassador Alejandro Orfila of Argentina, the other prominent bachelor-host-diplomat, is not to be outdone by Zahedi. He had a return-to-the-tango party beamed live on Argentine television. Here the new mediacracy diplomacy was used to glorify the Argentinean government, not abroad but to its own citizens. In February, Orfila had a mammoth and unprecedented party for the governors of the 50 United States. Orfila, the mediacracy diplomat, had the evening videotaped for television, and he left the other ambassadors present in awe and uncertainty over just what was going on.

The mediacracy, for its final element, includes transitory media figures. John Dean and Jeb Stuart Magruder may be felons under the old laws of Society but under the new they are princes to be rewarded with fortunes in book contracts and lecture fees. They have arrived as they never would have as mere Presidential aides.

The mediacracy is a society that might quarrel in public but it gets along remarkably well in private. During the last of the Nixon years Barbara Howar, a major media figure in her own right, gave an intimate dinner party attended by, among others, Henry Kissinger, Nicholas von Hoffman, and writer Larry King. “I went up to Kissinger and I said, ‘How in the hell can you work for that son of a bitch Nixon?” King says. “And even before there could be an answer Nick started chastising me for asking such a question in a social setting. And before I knew it Kissinger had left.”

“I don’t remember,” von Hoffman says now, “but it’s not out of character for me to act like that.”

• • •

The development of the mediacracy was inevitable once the media became transcendant in American life. Nathaniel West foresaw this in his novel Miss Lonelyhearts, the story of a male lovelorn columnist in a world where men and women led lives of noisy desperation and turned to him for help: “Dreams were once powerful, they have been made puerile by the movies, radio, and newspapers.”

West’s novel contained the seeds of prophecy. A day would come when the world of Miss Lonelyhearts would spread from the lovelorn column through the society pages to the entire paper and out to that great land of the media that sustained the people, that had replaced religion or nation or family. A day would come when religion’s vision of hell would be nothing compared to the threat of nuclear damnation transmitted by journalism. A day would come when pundits who pretended to touch the very flesh of events would package the world in neat 500-word columns or 90-second capsules, robbing history of its meaning. A day would come when current events dramas would appear in full color in 60 million homes each evening, usurping the life of drama and the drama of life. A day would come when the newspapers would evolve too, and the Washington Post, the print package of the future, would open up its forms and concepts. Picking up the Post each morning, one could believe he had bought the world for a mere 15 cents.

Washington is the center of the mediacracy because Washington is now the capital of the media, more the creator of myths than Hollywood in the 1930s. The stuff pours out of the city, coursing down on the public, and the people listen as they dress. They read the Post at breakfast. They listen to the all-news radio on the way to work. They listen to national and local news at night. They want to be Barbara Walters, not Faye Dunaway. They want to be Woodward or Bernstein, not Paul Newman. They want their own moment in the media.

• • •

The media are becoming the ultimate arbiters of American life, and the third Sunday of June 1974 will stand as an historic day in the annals of the mediacracy. On that morning readers of the Washington Post opened to the Style section and found a three-page oeuvre by Sally Quinn designed with the kind of graphic originality you once found only in magazines. The article was a major event in social reporting. It was like the day the 1917 Chicago Exposition opened. There stood Duchamps’ “Nude Descending a Staircare,” and there ended the romanticism of much of American art. Sally Quinn’s piece ended the romanticism of social reporting.

“The Law of Twelve Which Makes Washington Whirl, and the Boy From Pocatello,” as Quinn’s article was headlined, was a story of brazenness and guile and cunning familiar to the readers of Balzac or Proust, but unfamiliar to those whose cultural sustenance comes from the daily media. It told the story of Steve Martindale, a young public relations executive at Hill and Knowlton who set out to make it in the social whirl. He had succeeded in getting some of Washington’s most powerful figures to come to his rented house for parties. It was not a pretty story. It was as devastating a profile as had ever appeared in the social pages of a newspaper.

One should begin not with the article itself but with Ms. Quinn, for in the brave new world of the mediacracy the distinctions are gone between the reporter and the subject, between journalism and life, between public and private lives.

In her career Quinn already had shown the courage of a Hollywood Marine in crashing through the homilies and niceties of traditional social reportage. She wrote with a candor and perception that was absolutely unique, and she became the best social reporter Washington had ever seen. In past societies that was an accomplishment roughly on par with great ability at ice skating or yodeling, but in the mediacracy it was an achievement of the highest order.

But that was only the beginning, for she made herself the first goddess of the mediacracy. She made of her life one grand drama–her reporting became a continuing autobiographical journey into the upper reaches of the mediacracy.

Quinn slept in her editor’s bed, and she parcelled out intimacies to the media as it built its giant self-image. Those who live by the media die by the media, and when she arrived in the Big Apple to co-anchor the “CBS Morning News,” New York magazine ran a profile of her that took the image she had made and blew it up a hundredfold. New York said she had discussed the size of the penises of Washington politicians at a dinner party. She never had, but what could she say or do now? She was pursued by the image wherever she went. In the end she failed in New York, failed miserably. But she was able to cannibalize even her greatest defeat, turning it into an upcoming book on how difficult the life of a television star is, including stories about all the CBS executives who tried to put their hands on her thigh.

To the spectators to her life, Sally Quinn seemed a tissue of clippings, TV shows, quips, anecdotes, and telephone numbers, an object of envy and mistrust. After returning to the Post she went on Channel 4’s “Take It From Here” two mornings in a row with Erica Jong and Kate Millett, her media sisters, to discuss how difficult it was to be famous. It was a strange antidote to fame, like a man guilty of exposing himself taking a cure in a nudist camp. But the good matrons of Potomac and McLean and Takoma Park did not mind. They watched as they swept and polished and mopped and they prayed for just one night of that blessed unhappiness. That, after all, is what the mediacracy is all about.

Like much epochal art, Quinn’s Martindale profile was a work of calculation. She took all the insights and ideas about Washington social life she had gained and used them up in this one article. She described an incredibly fluid social world, a world that Julien Sorel would have found divine, a world where the great egos lined up at just about any trough to be wined and dined and massaged.

Quinn gave her “Laws of Twelve” for making it socially. “There must be a social hole to fill, a host or hostess role to be filled,” she began. And she went on to describe the depth and parameters of the hole that existed. She wrote that one must have a sponsor, an understanding of who’s in and who’s out, persistence, a subtle awareness of changing styles of entertaining, an inoffensive personality, and “a very thick skin.” The analysis was a tour de force, a mini-course in making it, a game plan for arrivistes.

Her choice of subject was as important as her analysis. Who was Steve Martindale anyway? He was a young man of surpassing pleasantness who became friendly with Joan Braden, the columnist’s wife, and through her and others began to give parties for the social superpowers of the capital. There were a score of others who had played the same game, played it longer, and were far better established. That wa just the point. Sally Quinn, an arbiter of the mediacracy, was writing about Martindale because she believed in this new society. She was a protector of the gates. She was too smart to challenge anyone of real consequence. “Steve is the only person Sally could have written the piece about and not hurt his career,” commented Peter Malatesta, a deputy assistant secretary in the Commerce Department and himself a charter member of the mediacracy.

“The Boy from Pocatello” went far beyond what is generally considered journalism in that almost all of the remarks cutting Martindale down came from anonymous individuals. There are, in fact, 25 such blind quotes in the article. When the piece reached the Post’s Sandy Rovner for final editing, she might normally have had some doubts–its thesis was based almost entirely on the statements of people who were willing to make the most nasty sort of personal comments as long as they did not have to stand behind their opinions. “But I knew the quotes were accurate,” Ms. Rovner says, “because I knew who most of the people were.”

And she did, for most of the quotes came from journalists or their wives (“a famous columnist,” “a newspaper man,” “a prominent columnist,” “the wife of a columnist,” “a well-known newspaper man,” “the wife of a television personality”), including a few important journalists on the Post itself. It is their mediacracy, after all, and they were merely pruning away at one poor chap who happened to trespass on their turf.

Closely akin to the use of blind quotes in this first great work of the mediacracy is the use of errors. In journalism, to err is inhuman, but in social reporting–the transformation of gossip into news culture–error is the very yeast of the stuff.

One can never be sure what is true, what is half true, and what is not true at all, and there lies the mystery. There are numerous factual errors in “The Boy from Pocatello.” Martindale had never gone to Holy Trinity Church in Georgetown, although the piece said he frequented it. He had never given a party for Adlai Stevenson, although the piece said he had. He was not on the board of the Martha Graham Foundation–there was, in fact, no such foundation. He had not gone tothe University of Idaho. Representative Wayne Owens was not from Idaho; he was from Utah. And Robert Gray, Washington head of Hill and Knowlton, had to suffer the ignominy not only of having one of his vice presidents savaged in print but to find his own name spelled “Grey” throughout the story.

The piece was published in a daily newspaper, that most transient of print mediums, and was gone the day it arrived–its meanings and myths entering into our lives. Steve Martindale now was a figure of notoriety or fame, whichever you preferred, though they were much the same.

• • •

One way to observe the triumph of the mediacracy is to contrast the Gridiron dinner, the establishment of the old journalist, with the Counter Gridiron, the establishment of the new journalist. For half a century or more, the Gridiron dinner was the most desired invitation inWashington journalism. Here, one evening each spring, the top men in big journalism, big business, and big government got together for an off-the-record evening of inside humor and inside stories and inside backslapping. Why, as the Saturday Evening Post said in 1955, the dinner had “become almost an official organ or function of the national government.”

But, alas, the fizz has gone out of the champagne. Starting in 1970 women journalists have picketed the all-male event, and the conventional moralists of women’s liberation see the refusal of many important politicians to attend as another victory against the vulgar forces of male chauvinism.

What really has been happening, however, is the emergence of a new journalistic establishment and the demise of the old, nudged along by women’s liberation. Ben Bradlee, the Post’s executive editor, has as good a sense of the politics of the emerging mediacracy as anyone in Washington. Back in 1967 or 1968, Bradlee remembers that columnist Marquis Childs and former Star editor Newbold Noyes came to tell him that he was next on the list to join the Gridiron. But Bradlee refused. He understood that the old mesh of government-journalism-business wasdying out, to be replaced by a new journalistic society.

The new establishment, begun as a protest, calls itself in splendid Orwellian syntax the “Counter Gridiron.” Last year Senator Charles Percy; Dan Rather; Senator Ed Muskie; CongressmanRobert Drinan; Martha Mitchell; Congressman John Brademas; former Attorney General Elliot Richardson; Woodward and Bernstein; and Stewart Mott, the philanthropist, were among those manning the Counter Gridiron barricades.

Another way to observe the triumph of the mediacracy is to compare the National Press Club, the institution of the old journalist, with the Washington Press Club, the institution of the new journalist. In January both organizations held their most important functions of the season. Traveling from one to the other was like moving through a time warp.

The National Press Club held its function, the inauguration of its new president, William Broom, on a Sunday afternoon. The National Press Club building on 14th Street in downtown Washington is a warren of wire services, radio networks, PR firms, foreign journalists, stringers, and flacks, topped by the club. One could not enter the grubby newsrooms of the past without thinking of human mortality. Even the metaphors of the old journalism dealt with death. Stories were killed or spiked. Clippings went to the morgue. There was nothing deader than yesterday’s news. One could not enter the lobby of the National Press Club building without catching a whiff of decay.

The club is the poor sister of Washington club life, but it has a certain seedy gentility. During the 1940s and 1950s it was the center of Washington journalism. Now there are 5,000 members, but only 1,000 could by any definition be called journalists, and many of these live by handout. Many of the members are in public relations, America’s most unique contribution to the professions, and many of them are lobbyists, and they allow the club what passes for grandeur.

At William Broom’s inauguration the universe as it exists was laid out with reasonable accuracy. Journalists have no illusions about equality, and the important people–PR executives, politicians, club officers, and a few journalists–were off by themselves in the East Lounge for free drinks and an elaborate buffet. The masses had to pay for their drinks, and many headed for the ballroom where Howard Devron and his band were playing. But nobody danced, for in the middle of the room two white-coated waiters sliced roast beef from two great pinkish legs. These were connoisseurs of free canapes and this was their meat, and they stacked slice after slice of the stuff on yellow rolls and sent it sailing down into their bellies on a tide of Scotch and soda or vodka and tomato juice. Then they pulled up folding chairs to the stage to wait for the activities.

The club had assembled a decent group of politicians–Mo Udall, Gene McCarthy, Liz Carpenter, James Symington, William Ruckelshaus–each to quip his way through five minutes, but most members were waiting for just one moment–the arrival of President Ford. Finally he was there, standing in the stage entrance. He came on reading off three-by-five cards and calling the new president “Bloom,” not “Broom.” Then it was treat time, and the President and his cadre of Secret Service agents plunged down into the crowd. The club members swirled and pushed their way toward him like teenyboppers at a Bobby Kennedy rally. They pressed at his hands, thrust their programs in his face for signature.

“Hello, Mr President.”

“Thank you, Mr. President.”

“He’s a nice guy.”

“That’s the first time I ever shook hands with a President.”

And then the President was gone, and soon most of them were gone and an hour later the club was nearly empty.

• • •

The Washington Press Club is a vision of the future, the triumph of the mediacracy. As headquarters for its 600 members, the club has a press pub in the Sheraton-Carlton Hotel, but there is no sense of permanence, of place. The club seems to exist among briefings and banquet halls and telephone messages. It is made up of journalists and government information spokesmen, and it is this organization that many of the new generation of journalists are joining.

The club’s annual “Salute to Congress” dinner was held in the ballroom of the Sheraton-Park Hotel. If Hildy Johnson and Walter Bums of The Front Page could only have been there. It was a black tie affair, and as Susanna McBee of the Washington Post explained, the members vied with one another for the honor of inviting celebrity politicos. Why there was Bonnie Angelo of Time with Senator James Buckley, John Marsh from the White House, and Sheila Wiedenfeld, Mrs. Ford’s press secretary. There was Mel Elfin of Newsweek. He had Justice Potter Stewart, Presidential press secretary Ron Nessen, Congressman Peter Rodino, and Congressman John Anderson. And Susanna McBee was not doing that badly herself, what with William Colby, the head of the CIA, James Lynn, the new head of OMB, and Laurence Silberman, then Acting Attorney General. But how about Katharine Graham with Arthur Bums and Henry Kissinger and both Symingtons, father and son?

It took David Halberstam, author of The Best and the Brightest–perhaps the best and the brightest account of the inner politics of Washington ever written–to make the most devastating comment about such affairs: “I don’t think journalists should shack up with news sources. The price you pay is to accept more or less what they’re saying. The people you really get information from won’t be seen with you, and can’t be seen with you, and would not be seen with you.”

Such caveats may sound petty, for the journalists of the mediacracy no longer meet politicians as supplicants, or even as voyeurs of power, but as equals. There they sat, warmed on whiskey and wine and brandy and self-congratulation, listening to various politicians perform for them. If there was one discordant element it was that Richard Reeves of New York and Bob Woodward of the Washington Post had not dressed in tuxedos. They stood talking together and one journalist turned to Jon Margolis of the Chicago Tribune and said, “What is this, some kind of protest?” But Reeves and Woodward were merely discussing the relative merits of their literary agents.

• • •

As for the social life of Washington, the mediacracy has both a private and a public aspect. The private aspect of it is indeed private, since the media put a cordon sanitaire around the parties and gatherings of their peers. As Art Buchwald says, “Kay Graham’s parties will never be covered.”

The private parties given by members of the mediacracy are probably the most desired invitations in Washington–the Easter party at the Buchwalds’, a dinner with Kay Graham, a trip to the Redskin games with the “gang,” or perhaps soon an evening at home with Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn. The best party of 1974 may well have been the evening that the mediacracy celebrated Art Buchwald’s birthday at his “The First Anniversary of the Saturday Night Massacre” tennis tournament at the McLean Indoor Tennis Center. William Ruckelshaus, Ted Kennedy, Sargent Shriver, William Simon, Rowland Evans, and Sally Quinn all made it. Phil Geyelin and Ben Bradlee challenged Joe Califano and Jack Valenti to a $100 match between the Wasps and the Dagos. And hours later, bad back and all, Bradlee won the main tournament. “The trophy was so important to him, but his friends turned thumbs down on his taking it to the Redskins game the next day,” says Rene Carpenter, the television personality. “We thought it was tacky of him.”

The public aspect of the society of mediacracy consists of the names and faces that are found in the social sections of the newspapers. Allison La Land says that at one time she read the accounts the morning after her parties as if they were reviews.

It often is said that such public social life is merely an extension of Washington’s eternal power game. It would be more correct to say that these are functions where those who live on the illusions and the rituals of power rather than their substance are fed more illusions and more rituals. Ambassadors are part of the brew: When the great hosts and hostesses of the city talk of their parties, they often will say, we’re having ten ambassadors or six ambassadors, as if they were talking about pieces in a band. The politicians one sees night after night at these affairs are in much the same category. They are either over the hill or they have never climbed a hill. William Saxbe is a case in point.

A garrulous and outspoken Ohio politician, Saxbe and his wife Dolly would not seem obvious candidates for the social whirl. But as Attorney General he wore the epaulets of power, and like the other major public figures of the city, he would have had to work to avoid being wined and dined and toasted half to death by courtiers noble and ignoble. The serious political figures of Washington simply do not have the time or the energy to step out night after night into the public social world of the mediacracy. But there are those like Saxbe whose work has just not taken, men distracted to the point nearly of self-indulgence, and they become part of the public society.

Just before leaving for India as ambassador, Saxbe ate his way through a month-long luncheon and dinner obstacle course, tunneling through a mountain of shrimp canapes and lobster bisques. Some of his close friends had not put in their requests early enough. And they watchedas the lucky hosts and hostesses lifted Bill and Dolly Saxbe through the social whirl like Sicilian peasants carrying their plaster saints through the streets on feast days.

One of the innumerable dinners was given by Tongsun Park, a Korean industrialist and one of the few mysterious public figures in Washington. “The difference between Park and Martindale is thatPark is a millionaire and gives expensive parties and Steve is not and does not,” said the wife of one prominent journalist. But the difference went far beyond that, for no one seemed to know just what Park did and what relationship he had to the Korean government. Indeed, just beforethe dinner party, Saxbe had been out at the Channel 26 studios taping an interview with Martin Agronsky. The two of them had joked about Park. Here they were going to this party, and yet they really did not know who or what Park really was.

The black tie dinner was held in the Georgetown Club on Wisconsin Avenue. The 93 guests in dinner jackets and gowns had their cocktails jostled together in the downstairs living room with its walls of old English linenfold. Then they walked upstairs to the dining room, a dark, low-ceilingedchamber with ornate Spanish wood panels. They sorely taxed the limits of the club. They sat back-to-back and jowl-to-jowl. At some tables they had to pass their noix de veau rotie and salade Aida down the row like adolescents at camp. There was a great din and as the dinner progressed and one understood why it took all the ingenuity of civilized society to make the act of masticating a desirable social function.

The guests washed down their quenelles de brochet à Ia Florentine with Chantefleur blanc and their asperges à la Milanese with Chateau Ia Grange 1969 and their conversations were as light as the wine. Some business was transacted. Martin Agronsky chanced to be sitting near Senator Ernest Hollings of South Carolina and lined him up for an interview. All in all it would have seemed a rather pleasant, innocuous evening, except that there was a nervous restrained energy of a sort found in gay bars of a class not one bit better than they have to be.

It was not the vices of the body–lust and narcissism–that were practiced here, however, for the men looked as if they measured out their passions by the spoonful and the women had bodies fed too long on Metrecal and chocolate mousse. If one needed further proof that the bodily viceswere not of great interest, one only had to look at Tandy Dickinson, a friend of Park’s. She sat in a blue dress with silver sequins that looked as if they had been riveted into her skin. She had a face and a figure that would cause impure thoughts in an aging Mormon. Yet no one noticed. No one cared, for it was one of the dirty little secrets of the public mediacracy that sex was of no great interest. Nor could it be for people who go out six nights a week. “How can you find time for sex?” said Kandy Stroud, late of Women’s Wear Daily. “You come home exhausted. You come home and you haven’t the time and you haven’t the energy.”

It was not the vices of the body, but the vices of the head–envy and striving–that were practiced here. During dessert, Betty Beale, the Washington Star society columnist, got up from her chair and moved to a seat directly behind Dolly Saxbe. Ms. Beale is as much the queen of the old social reporters as Ms. Quinn is of the new. Ms. Beale believed, or so she said, that the basic human motivation was not sex or self-preservation, but snobbishness, and she tried to be one with the subjects she wrote about. She traveled from one party to the next, almost never writing a mean or unkind word, indeed almost never taking out her notebook. She was not an unattractive woman, but there was always some little thing–a dab too much of lipstick, a ringlet of hair not quite right. She had a strange hoarse voice as if her vocal cords had been strained beyondrepair by the sounds of professional niceness. And she sat there mimicking Mrs. Saxbe’s every gesture, touching her arms and hands, laughing with her, whispering into her ear.

After the gondolas de poires in bowls of chipped ice, Attorney General Saxbe, a great bull of a man, got up to make his toast. “Every time a woman got pregnant in Mechanicsburg, two men left town. The town never grew,” he said. “If we go through an arms deal with Pakistan we’regoing to be as popular as a bastard at a family reunion. We’ll do the best we can, but we should raise our toast to our host. We are honored to be here and we toast you.

“Tongsun, we toast you for the excellent talent you’ve shown in everything,” Saxbe said. And Senator Hubert Humphrey and Senator Ted Stevens had their chance to praise Saxbe and Park. Then comedian Mark Russell came on to neatly roast Saxbe and Park on a spit of satire. Muriel Humphrey had heard many of the jokes five nights before at another dinner, but she laughed as heartily as ever and the Jamaican ambassador looked at his watch for it was already 11:10 and these things were supposed to get over at 11.

Finally everyone trooped downstairs again for liqueurs. The ambassadors made quick exits as did other guests, but Betty Beale and her husband, a lobbyist for Union Carbide, danced in great sweeping circles in the center of the room. One might easily have believed that the partyhad been in their honor.

• • •

The next day there would be papers to look at to see how the mediacracy had judged the evening, or if it had been judged at all. Many of the partygoers believed they were leading enviable lives because the media told them so, and they did not realize that the media are not life,the media take the place of life. They did not realize that certain tribal people are not far wrong in their taboo against the graven image, in their belief that such images suck their lives away.

But those at the party had only walk-on parts in the mediacracy’s drama. They are the courtiers and court jesters and supplicants in a Society that is emerging around and above them. The mediacracy is creating the first uniquely American aristocracy with its roots not in European feudalism or the industrial revolution but in a peculiarly American experience. The permanence of this Society is based on the impermanence and interchangeability of each individual, its stability based on its seeming instability. This is the beginning of a new age and of a new manners. The impact of the mediacracy on the lives of Americans is only beginning.