If the past year of campaign messaging has made you want to tear your hair out, George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum will give you a healthy dose of vexillological perspective. While today’s candidates attack each other on TV and Twitter, 19th and early-20th century candidates did it by inserting themselves onto American flags (a practice that’s now very, very illegal). What’s more, they didn’t even bother to get the flags right–in fact, local campaigners and the printers they hired sort of did whatever they wanted with the design.

The museum’s exhibit, entitled “Your Next President…! The Campaign Art of Mark and Rosalind Shenkman,” opens this Saturday, and traces the evolution of presidential campaign paraphernalia, with a focus on fabrics. Cotton and silk flags used to be as ubiquitous in presidential campaigns as lawn signs are today, until the trademarking of the American flag in 1905 finally stopped candidates from using it for political advertisement. The museum has several rooms full of the freewheeling 19th century flags, which make today’s political ad design teams look comparatively polished.

William Henry Harrison, known to most people as the guy who gave the longest inaugural address ever and then died a month later, was actually the first presidential candidate to leave behind campaign ephemera that used the flag. His strategy proved so successful that almost every candidate for the next half-century used the same basic idea. But the design of the flag wasn’t standardized until 1912, so flag printers in Harrison’s day didn’t think twice about printing flags with 17 stripes. Proper dimensions, too, clearly weren’t a thing yet:

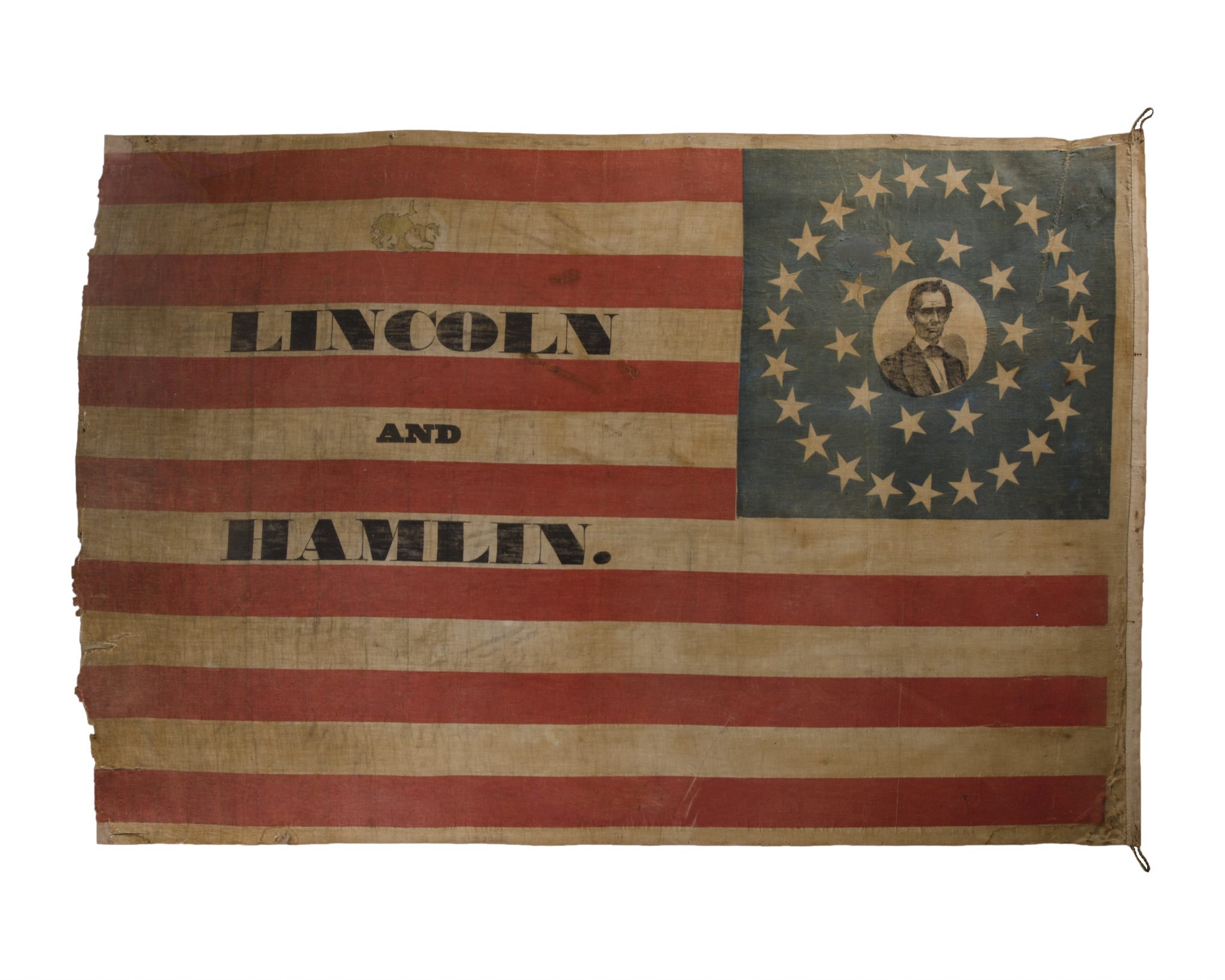

When Lincoln began to campaign for office a few decades later, he took flag interpretation to a new level. Here’s a Lincoln campaign flag in which he uses 35 stars to spell “Free”–with one outlying star meant to symbolize Nevada, which Lincoln wanted as part of the Union because it had a lot of natural silver resources (an in-joke that folks in 1864 would have gotten):

By the late 1800s, people were getting ticked off at the use of the American flag as political propaganda. So candidates got even more creative–and by the election of 1888, things devolved into what the museum calls “the battle of the bandannas.” The election saw Republican Benjamin Harrison going up against Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland, and the ad campaign played out principally in bandanna form. Cleveland’s running mate, Allen “Old Snuff” Thurman, was known for the red bandanna he kept in his pocket to blow out all of the snuff he frequently inhaled. The snot cloth became his most famous characteristic, and his supporters began waving red bandannas in support. Not to be outdone, the Harrison campaign parried with bandannas of their own, so that everyone could blow their noses on the flag:

After the Spanish-American War, Americans began to see the flag as a sacred symbol that shouldn’t be mired in political advertising (or snot). So in 1905, it became a trademarked design. With that, candidates had to search for other symbols to use on their campaign textiles. Teddy Roosevelt decided to use his own mouth, in this slightly unsettling design:

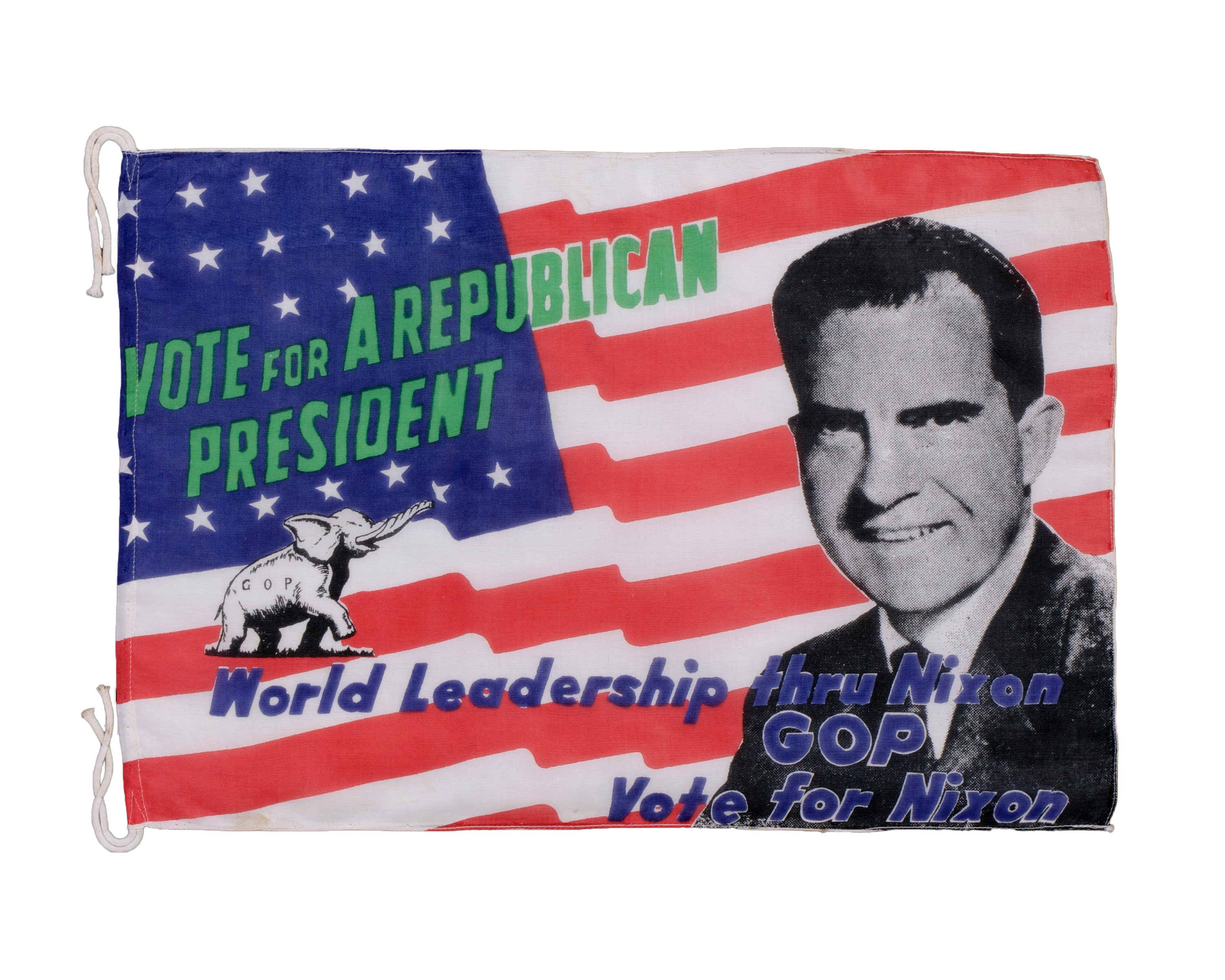

But over a half-century after the use of the flag was outlawed, it still cropped up from time to time. Taft used it in a 1912 campaign textile, and Nixon used it like it was no big deal in this 1960 ad (below). “We’re not even sure if this is legal,” says Jane Freundel Levey, a consulting curator at the museum’s Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection. “We hope someone doesn’t come and bust us.”

“Your Next President…! The Campaign Art of Mark and Rosalind Shenkman” runs until April 10, 2017 at the George Washington University Museum and the Textile Museum, 701 21st Street NW.