Last week Georgetown University announced it plans to offer preferential admission to undergraduate programs to the descendants of the 272 men, women, and children Maryland Jesuits sold to plantations in the South in 1838. Two Georgetown presidents, both Jesuits, organized the sale and the university profited from it. Other universities have slave sales in their pasts, but no others have taken such significant action toward reconciliation. In addition to the admission policy, Georgetown will formally apologize, build a memorial commemorating slaves who contributed to the university, open a slavery institute, and change the names of two campus buildings (formerly named after two presidents involved in the sale).

And yet the plan does not include financial assistance or scholarships for the descendants. As Adrienne Green wrote for the Atlantic, “Georgetown’s cost of attendance totals nearly $70,000—how will it ensure that these students can actually take advantage of the new offer?”

The answer is a little more nuanced than it first appears. Georgetown is a need-blind, full-need institution, which means admissions and financial aid are kept separate through the admissions process. When students are admitted, the university says it meets 100 percent of their financial need. During 2013-2014, 42 percent of undergraduates were on grant aid. “We will work with descendants to ensure they understand that their ability to pay will not be a barrier to attending Georgetown,” says Georgetown spokesperson Ryan King. “Over the last decade, Georgetown has provided nearly $1 billion in financial aid to qualified students who cannot otherwise afford to attend Georgetown.”

Georgetown’s financial packages do require some prospective students to work part-time jobs and take out loans. In 2013-2014, 27 percent of undergraduates had a federal or private loan. “We do not ask students to take out loans exceeding $17,500 per year,” King says. Low-income first-generation students won’t have to take out loans for more than $6,000 over their first four years, he says. Depending on Georgetown’s evaluation of what a family can pay, descendants could fall in either category. On top of Georgetown’s direct costs, which include tuition, class fees, and room and board–$65,926 for the first year and $66,296 for each continuing year–prospective students also have to handle what the university estimates as nearly $4,000 in “indirect” costs such as books, travel, and other personal expenses.

Karran Harper Royal does not think Georgetown is offering enough. “For descendants who go on to attend Georgetown, the university must offer scholarships, not just a leg up in admissions,” she wrote in a recent piece for the Washington Post. She and a group of more than 600 other descendants called for Georgetown to join them in creating a $1 billion foundation to help descendants attend any college. They have already raised $115,000 in seed money—the amount buyers paid in 1838 dollars for their 272 ancestors. In today’s dollars, that’s the equivalent of $3.3 million. Georgetown’s current endowment is $1.45 billion. The university has not hinted at starting a scholarship for the descendants of the enslaved families. “If Georgetown is going to atone for its part in slavery, descendants shouldn’t have to pay, either,” Harper Royal wrote.

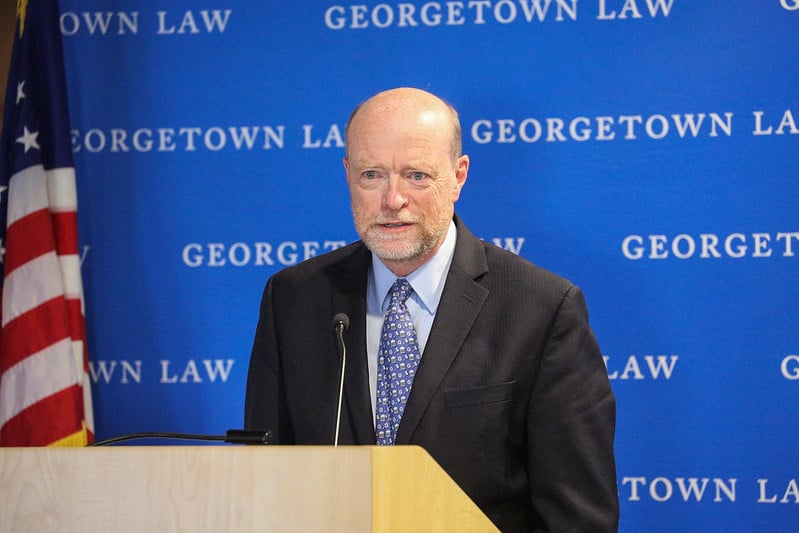

Georgetown will not comment on addressing this foundation specifically. The descendants “have perspectives that we will ensure have a central place in this work as we move forward,” said university president John DeGioia in his announcement last Thursday. “We will engage them both in reviewing this report, and in our efforts as we move forward.” As for financial assistance, we will have to wait and see.