My father made his latter senior years easy for his family. Unlike the resistant parents of many of my friends, he never objected to the help my brother and I hired for him. He agreed without hesitation when we explained we wanted to move him from the apartment building and friends he loved in Potomac to a place that would provide round-the-clock care.

After researching our options, we chose an assisted-living group home in Aspen Hill. It was furnished, so most of the things that would go with him would be sentimental and decorative as opposed to practical. My dad couldn’t really speak—he had dementia and aphasia—which meant it was up to me and my brother to make the decisions for him about what to bring.

We set about separating decades’ worth of belongings and memories into mundane categories: things to pack, things to store, things to donate, things to sell (though we ended up not selling anything). It would have been an impossible task had we allowed emotion to get the better of us.

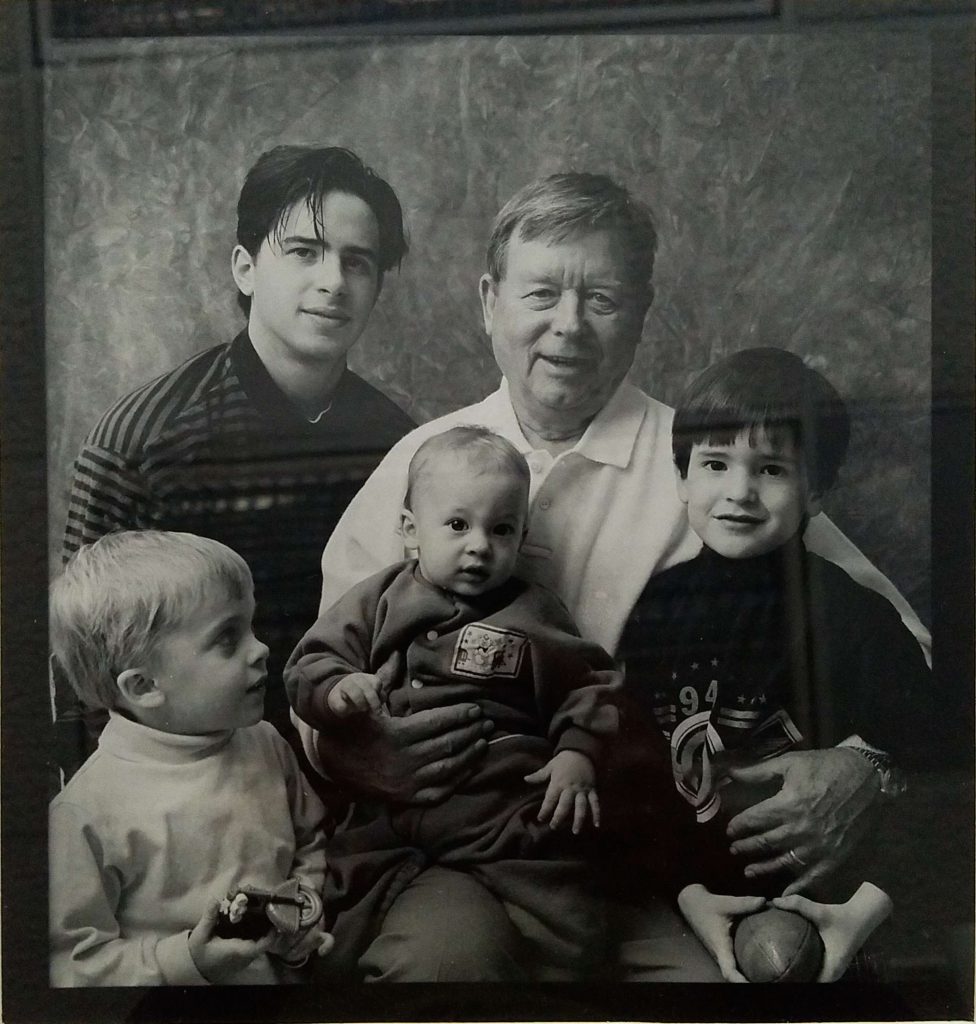

The toughest choices were about photographs. For Dad’s new walls, we pulled images of every important family member, from our late mother to the great-grandchildren who had just been born. When he opened his eyes in the morning, we wanted Dad to see the love.

I saved other photos of people I recognized, along with some especially striking pictures—and threw the remaining ones away. Without notes or names, they were meaningless.

Though it pained me at the time, I had apparently done what the pros would have advised. “We help our senior clients think about what they use now, not what they’ve accumulated over 30 years—we guide them toward keeping things they love,” says Kimberly McMahon, past president of the National Association of Senior Move Managers and co-owner of the Maryland consultancy Let’s Move. “If you have to come up with a rationale to keep something, you don’t need it.”

Not that I didn’t let emotion sneak in. I kept anything handwritten, such as old letters to or from my dad and notes he took at a Bible study. I also saved a lot of the artwork he collected during the decade he worked for RCA in Israel. A couple of large watercolors from Tel Aviv made the move with him to assisted living. One went on his bedroom wall. The home’s owner let us hang the largest painting in the shared dining room.

We changed the address on subscriptions so he would continue to get his magazines. We knew it was important to make sure Dad kept his large address book handy, so he’d be able to point to phone numbers when he wanted a caregiver to make a call.

We carefully selected items we thought would give him comfort. A cozy knitted throw and a lightweight down blanket from his niece made the trip. He had always been a devoted dog owner, mostly of schnauzers. I sent with him a small stuffed schnauzer that I’d spotted years earlier in a gift shop and that had always delighted him.

Though moving consultants can help with logistics and practical planning, those are the kinds of choices that only loved ones are truly qualified to make. My neighbor’s mother, for instance, loved music and birds. So when her mom moved into assisted living, my friend knew it was important to send with her a radio and a bird feeder that suctioned onto the outside of her bedroom window.

In part to spare Dad from living among all this sorting, we paid rent at his old apartment for a month after his move-out date. That gave us time to coordinate moving larger items to each of our houses and arrange donations of the rest. Goodwill, the Salvation Army, and A Wider Circle all pick up furniture for free. Dad was always committed to helping others, so we emphasized to him that most of his furniture would go to people in need. We think he understood.

It’s usually a given that seniors moving into assisted living will have to ad-just to a much smaller space. Susie Danick, co-owner of TAD Relocation, which helps seniors with space-planning and downsizing, stresses the importance of creating a layout in the new residence that’s not only comfortable but also safe.

“Ideally, you’ll have 30 inches of clearance [anywhere in the room] so that someone using a walker or wheelchair can maneuver in your space,” says Danick, whose company has helped with about 5,000 moves. “Even if the new resident is completely mobile, they’ll have friends who are not.” And in an emergency, it could be essential that the room be accessible to a stretcher.

Though many of his friends stopped by to wish him well, we didn’t mark Dad’s departure from his apartment building with a formal gathering, thinking it would be too emotional. We encouraged people instead to send cards to his new address, and he loved getting them. We assured him we’d bring him back to visit, which we did, to an enthusiastic welcome each time.

Dad lived a year and a half in the group house before he died. I was glad I’d kept so much of his Israeli artwork—after his funeral service, I gave much of it away to friends and family, confident those pieces would be a warm reminder of my father to those who loved and appreciated him.

8 Tips for Downsizing an Aging Parent’s Home

Moving Mom or Dad into assisted living can feel overwhelming. Here are pointers to keep in mind.

- Set deadlines for various benchmarks of the move-out process and put them on a calendar so you’ll be motivated to meet them.

- If your parent is able to participate in the move, respect his or her wishes whenever possible. An item that might not make sense to you might mean the world to your loved one.

- Rather than pack up an entire collection, send one representative piece of it to the new residence.

- Emphasize the good your parent is doing by donating items that can’t make the move.

- Use the best stuff: If your loved one can take only one set of utensils, why shouldn’t it be the sterling silver?

- Keep only special framed photos and al-bums. Scan the rest into a digital archive.

- Pack all jewelry and valuables yourself.

- If your parent will have limited closet space, keep out-of-season clothes in storage and rotate them in as necessary.

This article appears in the November 2016 issue of Washingtonian.