Marion Christopher Barry, the only son of the most famous politician in DC history, spent the last months of his life living off and on with a girlfriend in Wellington Park, a gated complex of apartments in a neighborhood known for crime, drugs, and despair. On the day before he died last August, he was trying to find a new place to live. “I want out,” he had told his friend Liz Matory. “I don’t want to go back.”

It had been a tough year and a half. Marion Barry had died in late 2014. Chris, as his son was called, had been drubbed in the election to replace him. His construction business had faltered. The house he’d lived in with his father had been put up for sale. He was essentially homeless.

Friends said he was self-medicating with PCP and with K-2, the synthetic marijuana often called Scooby Snax. When Chris called in August, Matory came to his aid. Friends since early childhood, they had lost touch while she got degrees in law and business and had recently reconnected. “I wanted to help Chris find his core,” she says.

Matory picked up Barry and a friend to help with the move. She says Chris had lined up an apartment but it had fallen through. So they loaded Barry’s tools into a U-Haul and moved them into a storage unit. Still, Matory says, her old friend seemed in good spirits. His construction company had just landed a contract to clean and paint public schools. As they drove, he pointed out buildings he dreamed of renovating, empty lots he wanted to develop. He waved to friends.

Later, Matory drove Barry back to Wellington Park. They cracked beers and chatted in the courtyard. “Tonight I’m going to get a good night’s sleep,” she says Barry told her. “Tomorrow I’ll put on some fresh clothes and start over.” Matory left around 10 o’clock.

A few hours later, she got a call from Barry’s cousin, Andree Clark. “Liz, they’re saying that cousin’s dead,” he said. “They’re saying Chris is dead, man.”

The police report says Barry had stepped out of the apartment and smoked PCP and K-2. Back inside, he started acting erratically. Then he “suddenly ‘dropped.’ ” At George Washington University Hospital, friends gathered as doctors worked to save him. They first reported they had restored his pulse, but they couldn’t maintain it. He was pronounced dead at 2:11 am.

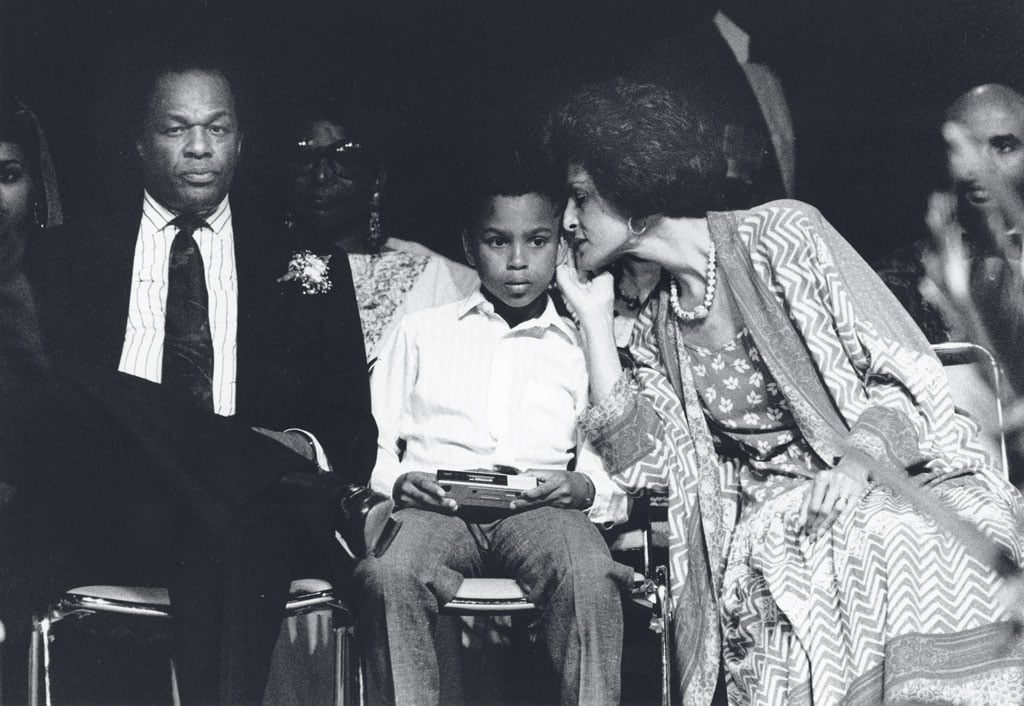

Eight days after his death, Barry lay in repose in a cherry-wood casket at Temple of Praise, the megachurch in Southeast DC along the Prince George’s County line.

It wasn’t the sort of funeral that typically follows an overdose in a grim little apartment. Hundreds of mourners paid homage. Mayor Muriel Bowser was there along with members of the DC Council, lawyers, clergy, journalists, a who’s who of the local political elite. “He was the son of the king,” said his godmother, Norma Jenkins Stewart.

Bowser spoke of trading texts with Barry about helping those in need: “The last one was just a week ago.”

The most personal tribute came from Lalanya Masters Abner, daughter of his stepmother, Cora Masters Barry. Abner said she was “protective and defensive” of the little brother who’d taught her how to love. “People wanted to discuss my brother’s struggles,” she said. “Not interested. Not . . . interested.”

It was a fitting statement—though may-be not in the way she intended. The prince had a rap sheet that had started with shoplifting at age 19 and descended to assaulting a police officer and a series of arrests for drug possession.

“We all knew Christopher had problems with drugs,” says Denise Rolark Barnes, publisher of the Washington Informer, an African-American newspaper based in Congress Heights. “We all wanted to create a program for Christopher.” Yet no one did.

You guys need to stop enabling him and get him some help,” Johnny Allem told Marion Barry. ‘I want you do it,’ Barry said.

Chris Barry is hardly the only child of power and privilege to have his life veer off course—various political scions with names like Kennedy and Bush have known trouble with addiction. But his demise seems particularly tragic. During his 36 years, he lived a life that might have been out of a Victorian novel, one that brought him into the highest realms of Washington society—and its most blighted corners.

The same was true of his famous father. But while Marion Barry was the author of his triumphs and troubles, many of the turns in Chris’s life resulted from the action—or inaction—of others.

Also unlike Marion Barry—born in poverty in rural Mississippi—Christopher Barry was a son of the Washington political community his father had helped create. Indeed, in talking to dozens of his friends, family members, and associates, I discovered a young man who had the potential to be a leader more charismatic, authentic, and effective than his father. His story left a question: If it takes a village to raise a child, why couldn’t a village of loyal friends and local political powerhouses save him?

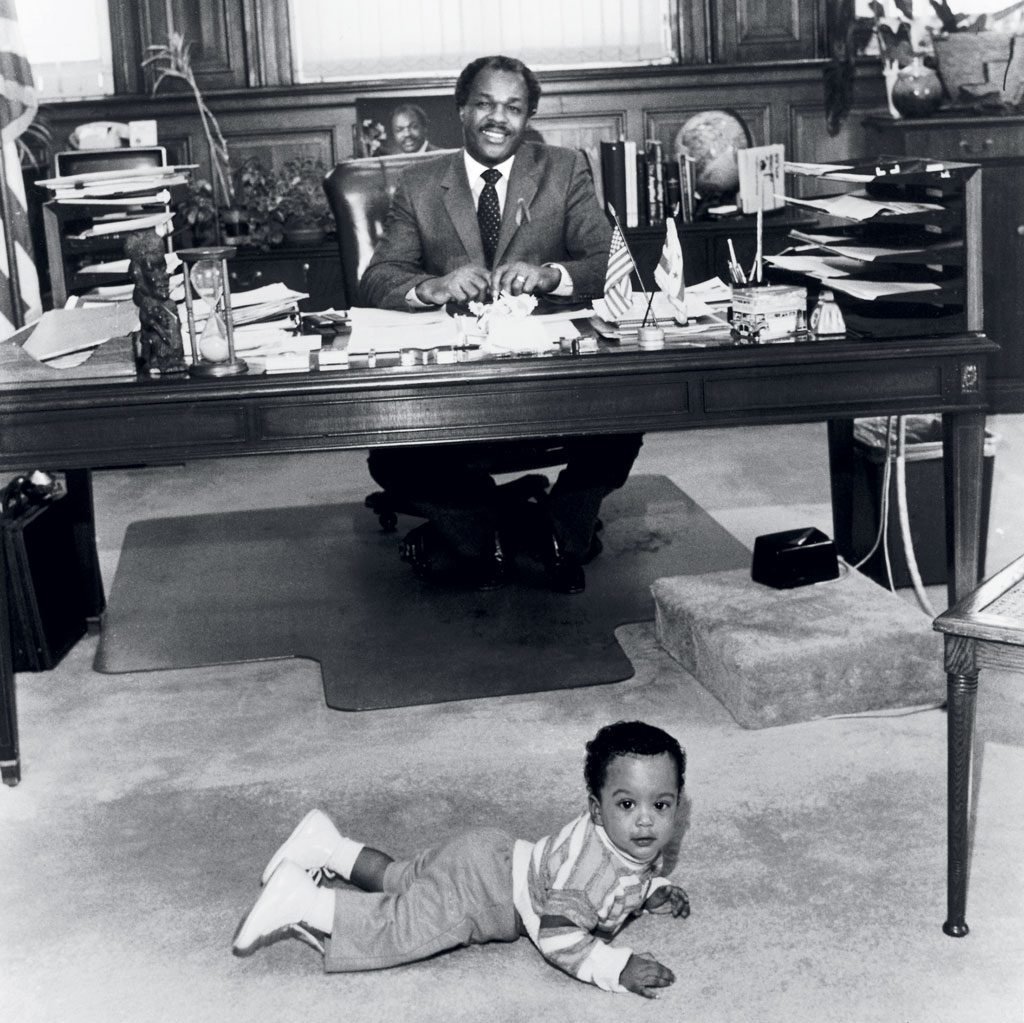

Marion Christopher Barry was born in 1980 during his father’s first term. At 44, the mayor was handsome and commanding. His wife, Effi Slaughter Barry, was tall and lean, stylish and charming.

The family represented a new, glamorous face of black Washington. The second mayor of DC’s home-rule era, Marion Barry had assembled a dynamic cabinet led by African-Americans, the nucleus of a political class in a city where local politics was less than a decade old. When Barry ran for reelection in 1982, images of Christopher crawling across his office rug—à la John F. Kennedy Jr. in the Oval Office—became a campaign prop.

When it was time for school, Marion and Effi sent their son to Tots, a favorite nursery school of the African-American elite. Every morning, a security detail drove Chris from Hillcrest, east of the Anacostia, to the school in Petworth, closer to the upscale, largely African-American Gold Coast.

“People who wanted the best for their child—doctors, lawyers, and high government officials—sent them to Tots,” says Clifford Davenport, son of the school’s founders, Carlise and Charles Davenport. “Our students went on to private schools like Sidwell Friends, St. Albans, National Cathedral, and Bullis.” Marion and Effi, Davenport says, “came to every play, every school event.”

“Chris was a natural politician even when he was two,” says Mori Diane, a classmate who is now a lawyer in London. “He worked the playroom like a pro. Everyone loved him.”

Downtown, though, the elder Barry was finding that running a big city was grueling. “You’ve got to find a way not to be over-consumed by the job, because it destroys you,” he told a reporter at the time. “I really understand a lot of politicians winding up as alcoholics or pill-poppers, because the pressures are so enormous.”

Rather than go home at night, the mayor attended meetings and hit nightclubs. He began a series of affairs, first with a woman named Karen Johnson. According to her diary and police reports, Marion Barry would repair to her apartment for marijuana and cocaine.

When news of her husband’s meanderings made the papers, Effi called him a “night owl” and stuck to the task of raising their son.

The night owl, though, sometimes showed up at Tots unannounced in the middle of the school day. Clifford Davenport was impressed at the way the dark-blue car with tinted windows pulled up to the curb and delivered the mayor. “Then,” Davenport says, “I found out that Rasheeda Moore lived around the corner on Taylor Street.”

Washington would soon learn all about Moore. She was the paramour who, on January 18, 1990, lured Marion Barry to the Vista International Hotel, where federal agents arrested him while he was smoking crack. The bust upended the city’s political order. It changed Christopher’s life even more.

The night of the arrest, cameras staked out the Barry family’s red-brick Colonial. “I didn’t know what to do,” Effi Barry later told the Washington Post. “I ran into the room and I looked at my son. He was still sleeping soundly. I just stood there and cried.”

A car pulled past the TV vans and into the driveway. Carlise Davenport got out. The head of Tots woke Christopher, wrapped him in her overcoat, and drove him to her home on upper 16th Street.

Christopher was in fourth grade at St. Albans. Everyone in the school knew who he was. “It was very, very hard for him,” says Mori Diane.

Edie Ching, a parent of two St. Albans students at the time, remembers Effi Barry as a doting mom. Chris’s embattled father, on the other hand, was less of a presence. Every spring, the school held a field day when parents could take part in events with their sons. Marion Barry did show up for that, with a purple jumpsuit, an entourage, and cameras. He participated in one event and left. “All of us looked at one another and felt so bad for Chris,” Ching says. “Marion Barry came—for himself.”

Still, even as his family’s political power was crumbling, the boy was lifted by the elite community to which that power had won him access. Mori Diane, for instance, was headed to Senegal that summer to visit family; his father invited Christopher to join them. As Marion was on trial and Effi sat in the second row in federal court, Chris spent much of the summer an ocean away.

Chris didn’t go back to St. Albans. After a trial that aired Marion’s sexual dalliances, Effi moved out. The next year, Marion was in federal prison. Chris, meanwhile, would move with his mother to Hampton, Virginia. Instead of going to the most famous prep school in the nation’s capital, he’d be starting public school in a city where no one knew him.

Marion Barry spent six months behind bars, got out, and immediately began plotting a return to power. He moved in with his longtime friend Cora Masters. They married in 1994, the same year Barry engineered what might be the most remarkable comeback in American political history.

For Chris, though, life hadn’t become any more stable. In Cora Barry’s telling, Effi phoned Marion one day to say their son was hard to handle and having trouble at school. She wanted to send him to military school. Cora had a better idea. She says she urged him to bring his son to Washington. So Chris moved back to DC and attended Jefferson Junior High in Southwest, a long way from St. Albans.

From Cora Barry’s perspective, Christopher grew up in a “good environment” with “lots of love, lots of opportunity, lots of support.” Marion Barry “indulged his son” and took him on trips to France, Africa, and Japan. But she does allow that his father wasn’t a constant presence: “It’s an occupational hazard of growing up a political kid—like a preacher’s kid.”

On the night of the arrest, Effi Barry peeked into her son’s room. ‘He was still sleeping soundly. I just stood there and cried.’

Friends paint a bleaker picture. Chris was so unmoored that he left his father and Cora for at least six months and moved in with Carlise Davenport, according to Clifford Davenport. (Via a spokeswoman, Cora Barry says this was not the case.)

Eventually, Effi moved back to the District, living in a condo on Connecticut Avenue just below Chevy Chase Circle. Her son, by then a senior at nearby Wilson High, was living a life whose geography spanned DC’s various worlds: his father’s home base in Southeast; the Davenports’ near the affluent, predominantly black Gold Coast; and his mother’s along one of Washington’s toniest avenues.

“Chris shuffled from house to house,” recalls Liz Matory, who had known him since their days at Tots. “He was very close with his mother, but his home life was unsettled at best.”

In his teens, Chris grew to resemble the man his father had been in his prime. “Christopher looked like a prince,” says Jim Graham, a former council member who was close to the father and son, “and had all the attributes of one: beautiful, stately, smart, engaging. He was easy to fall in love with.”

The word that most friends and acquaintances use to describe him is loyal. Curtis Leftwich, who went to St. Albans with Barry and remained close, remembers his friend showing up at pickup basketball games with his St. Albans buddies years after he left the private school and had gone on to Wilson.

Says Dyana Forester, who knew Barry in junior high and become close to him at Wilson: “He dealt with who his father was by using humor. He always wanted to get to the punch line first. He was brilliant. Being the class clown was his defense.” At his graduation from Wilson, Chris was part of the group who blew up the beach ball and tossed it around.

But it wasn’t easy. “Christopher was always in stress,” says Walter Faggett, a long-time physician to the family. “In his teenage years, he started to experiment.”

Faggett, a University of Michigan–trained doctor and former DC health official with a focus on adolescent medicine and addiction, had known Chris since he was a kid. He says he saw something that might have slipped past classmates who regarded Chris as just a handsome cutup. Some of them used to wait for him after school and ask, “Hey, got any spare crack from your father?” Says Faggett: “Kids can be brutal.”

“Christopher was self-medicating to blot out the pain and stress of his life,” he says.

Marion Barry was aware his son was suffering, Faggett says, and he knew what he was up to. But the mayor wasn’t in any position to admonish him. Friends such as Clifford Davenport stepped in.

“Listen, Christopher,” Davenport remembers telling the younger Barry when he was at Wilson, “I can walk down the street with a joint and a cop will tell me to put it out. The same cop sees you with a joint, knows your name is Barry, and he locks you up.”

“I get it,” Chris said.

The night of February 18, 2005, DC cops responded to reports of loud noise and potential domestic violence at an apartment up the street from police headquarters. At the door, they heard music and smelled marijuana. They knocked.

“Police!” they said. No one responded. The door was unlocked. They opened the door and again yelled, “Police!”

Chris walked out of the bathroom.

“Come outside,” one of the officers said. “We need to talk to you.”

“One second,” Barry said.

According to court documents, Barry tried to close the door on an officer’s arm, then put him in a head lock and started punching his face. It took three officers to bring Chris down.

By this point, Chris was seven years out of Wilson High—he had graduated the same year his father ended his fourth and final term as mayor. The intervening time had been rough on the son. He had enrolled at Hampton University, where his mother taught. But he left after his first year and drifted between the District and the Virginia peninsula, where his rap sheet began with shoplifting in 1999.

“Chris got into the party scene at Hampton and dropped out,” says his old friend Mori Diane, who in the meantime had graduated from Georgetown and earned a law degree at Tulane. “He took some architectural-design classes at UDC. I remember him walking around DC with a knapsack full of sketchpads and pencils. He would stop and sketch buildings with such accuracy. He threw himself into it, but then he would get distracted and didn’t finish.”

Marion Barry, meanwhile, had jumped right back into politics, winning a seat on the DC Council in 2004 at age 68. He’d been in trouble, too. In 2002, US Park Police found traces of marijuana and cocaine in his car. As his son was facing assault charges, prosecutors were investigating the father for failing to pay taxes. He would later plead guilty and be sentenced to probation.

In spring 2005, Marion and Effi turned to A. Scott Bolden, a prominent, politically connected lawyer, to defend their son. He met Chris and his parents in the conference room of his law firm, Reed Smith. “It was the hardest meeting I’ve had in my 30 years of practicing law,” Bolden recalls. “I witnessed a conversation about arrest and addiction. I witnessed all three struggle with their past. Marion and Effi were trying to parent him, to correct him. It was steeped in politics, personalities, and family pain.”

In the end, Bolden got prosecutors to agree to a “deferred-sentencing agreement” so that Chris wouldn’t serve jail time. That followed a pattern applying to both Barrys—break the law, face few consequences. Chris could have confronted felony charges for assaulting a police officer, but he pleaded guilty to simple assault. Provided he steered clear of the law and stayed clean, he would only have to attend drug treatment and perform community service.

But Bolden says Chris tested positive for marijuana and breached the agreement. They renegotiated, and prosecutors extended the deferred sentence, giving him another chance. In the end, Christopher successfully completed the programs and all charges were dismissed.

Was there any discussion about putting Christopher into rehab? “Not in the conversations I heard,” Bolden says. “They did discuss it in terms of a health issue.”

The lawyer’s time with the Barry family during the 2005 case gave him a window into Chris’s life: “He felt an enormous pressure to succeed. He was torn between being himself and meeting the expectations of the public, exacerbated by his father. That becomes more difficult as you get older, especially if you are perceived as being less successful than your father.”

Then in 2007, the person in Chris’s life most able to give him unconditional love died of cancer. He and his mother had a close bond that got tighter as Effi’s disease spread. Her mother, Polly Lee Harris, told the Washington Post that the two would talk until 3 or 4 in the morning: “She always had time for him.”

Says former DC Council chair Kwame Brown: “He lived in a lot of pain about his mother dying. He never got rid of it.”

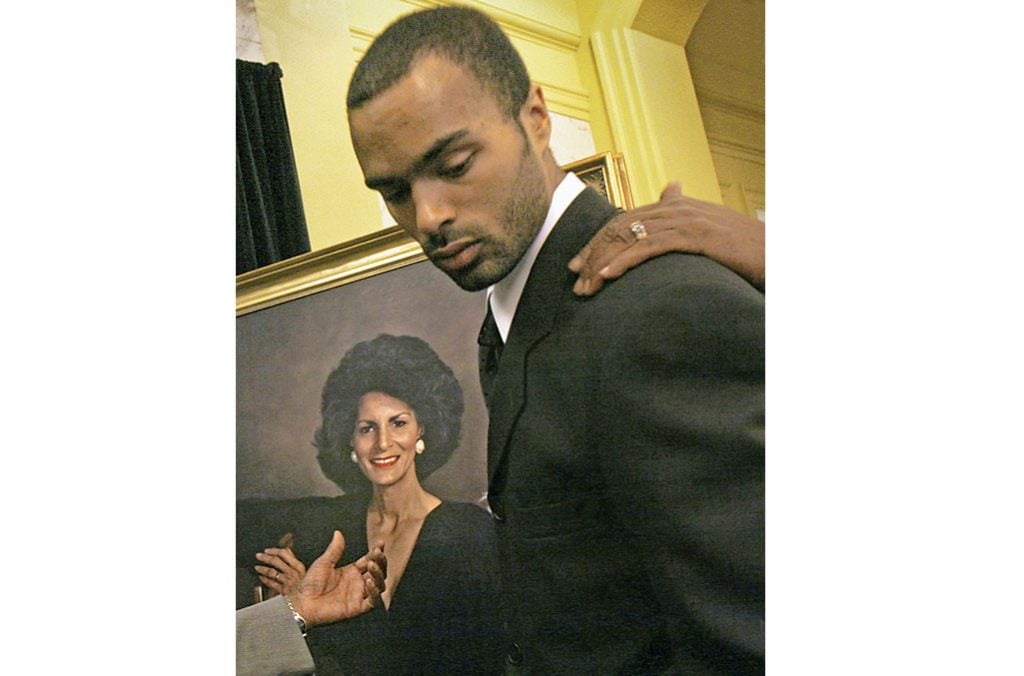

Chris spoke at Effi’s funeral: “I don’t ask God, ‘Why did this happen?’ I just thank him that he gave me 27 years.” He never mentioned his father, but after they left the podium, both Barrys embraced and the crowd met them with applause.

Effi’s mother rendered her own verdict: “All of my grandson’s problems are laid right at the feet of his so-called father, Marion Barry,” she told the Washington Post. “He was never a father. He was never home.”

In the spring of 2011, Marion Barry sought help once again from Dr. Walter Faggett.

Police had been called to his son’s apartment on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue in response to screaming and loud noises. When they arrived, Chris refused to open the door. He jumped out of the third-floor window, leaving behind sandwich bags of marijuana, a vial of liquid PCP, and blood on the floor.

Police convinced him to return. He showed up wearing shorts, a T-shirt, and blood-soaked socks. He told cops he had been “tripping,” according to court documents, and had begun to smash stuff in the apartment. He tested positive for PCP.

Faggett knew it was nearly impossible to force an adult into a hospital for drug treatment. Marion Barry pleaded for help. “I invoked the FD-12 process,” Faggett says. “It allows the forcible hospitalization of a patient for 72 hours if that person is a danger to himself or the community.”

Faggett and Marion met at Howard University Hospital’s emergency room to admit Chris. That was one of the few times that his addiction was treated medically, according to family, friends, and people close to his father.

But the forcible hospitalization at Howard ended particularly abruptly. Chris stayed the 72 hours, then left—against medical advice. He ripped the tubes out of his IV and walked out. “I called him on his cell phone and asked him to meet me at the Starbucks near the hospital, just so I could take out the IV,” Faggett says. “At least he agreed to that.”

Around the same time, Chris connected with another member of the political community he knew through his father: Jim Graham, then a council member. Graham had been public about his battle with alcohol and his daily attendance at “clean and sober” meetings at the Community for Creative Non-Violence homeless shelter. “Chris came with me once a week for a while,” Graham says. “I don’t think he ever shared. He never really got into the program. He just stopped going.”

The law wouldn’t be pushing him to clean up his act. After the PCP arrest, prosecutors added up Chris Barry’s many offenses and asked the judge for a nine-month sentence, drug testing and treatment, grief counseling, and anger-management classes. But Chris—this time represented by Frederick Cooke Jr., another fixture on the political scene—wound up not doing jail time.

A few years later, Marion Barry stopped Johnny Allem outside his DC Council office and asked him to come in and chat. Allem had worked on many of Barry’s campaigns and remained close to him. After decades in political consulting, Allem had dedicated his life to addiction recovery and later founded a treatment center. Barry asked him to help with his son’s addiction.

“You guys need to stop enabling him and get him some help,” Allem recalls telling Barry.

“I want you to do it,” Barry said.

“I don’t mind helping,” Allem responded, “but you have to do it.”

Barry, who had once extolled the virtues of his own recovery, never did. Despite his proximity, Allem says he doesn’t know whether Chris ever did a serious stint in treatment. (From what Washingtonian could ascertain from friends and public records, he briefly attended drug-treatment facilities in California and Frederick, but there were no long-term efforts.)

Chris Barry told Liz Matory: “My father and I could run circles around people high.”

In Marion Barry’s final years, he and Chris lived in a house together on Talbert Street in the Hillsdale section above Anacostia. On a steep rise above Good Hope Road, the two-story, white clapboard house had a view across the river to the monuments.

With the former mayor now ensconced as a DC Council member, the son was trying to develop a contracting business. He had named it Efficiency Contractors, after his mother. The idea was that he would gather crews from rough neighborhoods, then find contracts for demolition, painting, and cleaning.

But Chris struggled. He lacked a back office, says Scottie Irving of Blue Skye Development, which subcontracted Efficiency for work on schools and rec centers. “Chris had problems all CBEs have,” Irving says, referring to the program that provides contracting preference for local businesses. “He needed consistency of work. None of us have it.”

By this point, Marion’s health was deteriorating. Marion and Cora had long since separated, and Chris became a principal caregiver. When his dad showed up for political events, Chris often pushed the wheelchair. “His father had to depend on him,” says publisher Denise Rolark Barnes. “Marion knew he had not been a great father to his son, but Christopher learned how to be a great son to his father.”

There was one more thing Marion wanted from his son. In the middle of 2014, the former mayor called Jim Graham into his office to talk about Chris. But the agenda wasn’t recovery, sobriety, or safety. “I want to resign in the middle of my next term so that Christopher can run and replace me,” Barry said. “Can I count on you to support Christopher and help in any way you can?”

Marion Barry had been plotting the succession for years. It seemed far-fetched. For one thing, he had never shown much interest in mentoring his son in the political game. For another, Chris had never shown much interest in politics. But the man who had bounced back from a videotaped crack bust was known to pull off political miracles.

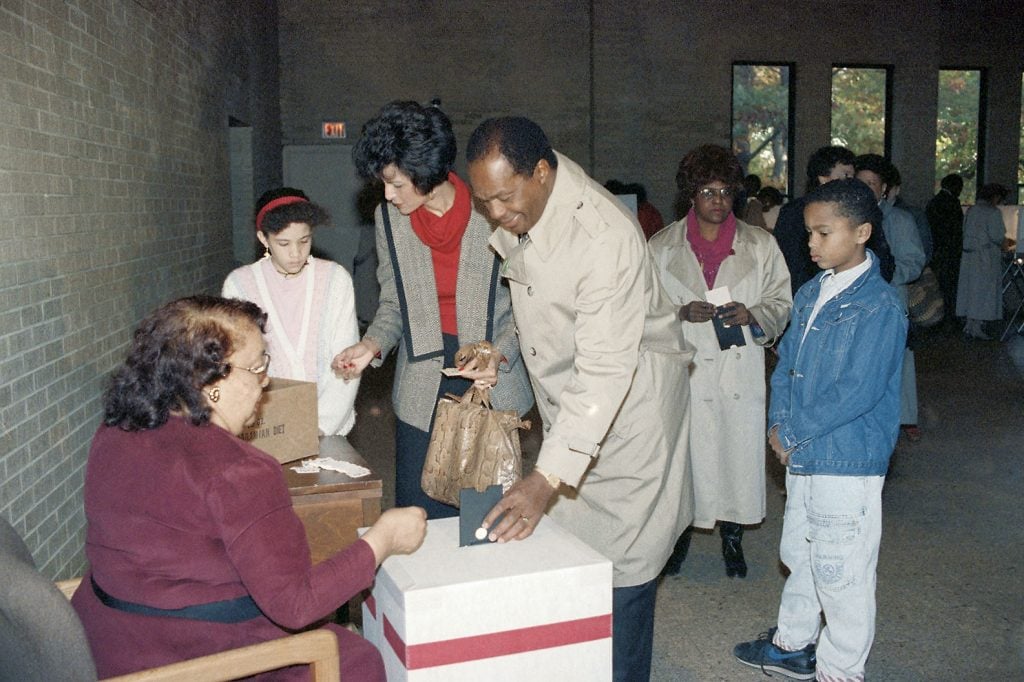

This time, he never had the chance. Marion Barry died on November 23, 2014. Eight days later, thousands gathered at the Washington Convention Center to celebrate his life, capping a three-day spectacle.

“They say DC will never be the same because Marion Barry’s gone,” Chris told the crowd in an address both loving and eloquent. “They’re right, because now there’s thousands of—millions of Marion Barrys out there. He’ll never die.”

His cell phone never died. His son took it as his own. Every time he made a call, “Marion Barry” showed up on the recipient’s phone.

More than 20 candidates filed to run in the special election to replace the late former mayor on the DC Council. One of them was named Marion C. Barry. Though he’d always gone by his middle name, Chris decided to campaign using his father’s name.

“I told him not to run,” Faggett says. “He was not ready. That kind of stress he did not need.”

Chris reached back to a few of his longtime friends to run his campaign. His old Wilson High pal Dyana Forester—who’d gone into politics as an ANC commissioner and later became an operative for unions—joined the group one day at the Talbert Street house and pulled her friend aside. “You don’t have to do this now,” she says she told him.

“I feel a strong responsibility to carry on my father’s legacy,” she remembers him replying. “I think I can win.”

As a campaigner, Chris had his dad’s instinct for playing to the crowd. At the Martin Luther King Jr. Day parade, he sported a cowboy hat and rode horseback. But while Chris was showing well by gathering his “Barry brigade” to clean vacant lots, opponents were gathering votes and filling their campaign coffers.

“He saw his father’s public way of campaigning,” says Forester. “He didn’t understand the strategic decisions made behind the scenes it took to win.”

In the midst of the campaign, he needed $20,000 to pay Efficiency’s crews. According to one of his managers, they had surrounded the construction trailer and refused to leave until Barry came through.

But at the bank, the teller said a check hadn’t cleared and his account had a negative balance. “I’m going to have someone meet you when you get off,” he threatened, according to the affidavit for his arrest warrant. He grabbed a trash can and chucked it over the Plexiglass partition. It smashed a surveillance camera. Police issued an arrest warrant. The following week, Chris turned himself in and pleaded not guilty.

“I’m going to stay the course and work hard to finish my father’s term in office and continuing the Barry tradition of being the voice for the people of Ward 8,” he told media outside the courthouse.

Graham says he took him aside after the bank incident. “For your own sake and the sake of the campaign, you have to get sober,” he recalls telling Chris. “The last thing Ward 8 voters need is a drug-addicted council member. I want you to hold a press conference to say you will go to rehab meetings again. People need to know you are serious about recovery.”

It never happened. On Election Day, just 554 people voted for Marion C. Barry. He finished sixth.

For Chris, the defeat seemed to clarify some things about the village that had raised him. His father’s old funders contributed little to his campaign. Trayon White, the man who eventually won Marion’s old seat, had gotten much more mentoring from the former mayor than Chris ever had. “When I really needed his guidance,” Chris told a Washington City Paper reporter about his father, “he was off on his own thing.”

Mori Diane was at a picnic at a friend’s home outside London when he got word that his friend had died.

“I flew into a rage,” he says. “Then I flew home.”

After his defeat, Chris had largely dropped from the political radar. His Facebook posts had become dark and angry. But it turns out he and Diane had talked three weeks before about Chris’s drug use. He had promised to get clean, focus on his business, and start taking classes at UDC.

Others members of Chris’s old circle mourned separately. Friends from Wilson arranged a candlelight vigil. Polly Lee Harris, the maternal grandmother who’d been such a fierce critic of Chris’s father, came up from Hampton for a private funeral for close friends. Then there was the public memorial at Temple of Praise, organized by Cora Barry.

A few months later, on November 23, Marion Barry’s tombstone was dedicated at Congressional Cemetery, amid the graves of senators and congressmen. It was two years after his death, and the event brought the old political community back together.

Barry had bought the adjoining plot for his son. But Harris, serving as next of kin, had her grandson’s body cremated rather than placed next to his father’s. She had slammed Marion as an unfit father, and now she was able to reunite Chris with his mother. At Congressional, the father’s ornate tombstone includes a tribute to the son—beneath his father’s bust in bronze relief. But Chris isn’t there.

Editor at large Harry Jaffe is coauthor of “Dream City,” about Marion Barry’s Washington, and author of “Why Bernie Sanders Matters,” a biography of the former presidential candidate. He can be reached at hsjaffe@washingtonian.com. On Twitter, he’s @harryjaffe. Editorial fellow Sydney MaHan contributed research and reporting to this article.