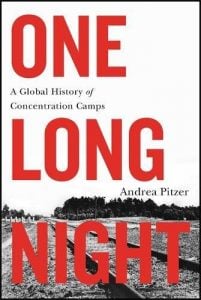

Author and journalist Andrea Pitzer was still working on her first book, The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, when she decided to write her second. Her research required a panoramic history of concentration camps, but what she required didn’t yet exist. So she decided to write it herself.

It took five years of full-time work, but Pitzer’s One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps is finally finished. The book takes its name from an Elie Wiesel quote, but it covers far more than Auschwitz and its contemporaries. When the book was being written, the author wondered whether people would be able to see the its relevance to their lives today. Now being released amid a global rise of nationalism and rhetoric that echoes dangerous propaganda of the past, the book is perhaps more relevant than Pitzer, who lives in Falls Church, would like it to be.

“I wish it weren’t the case that that problem went away,” she says. “I would be ok to still have that problem because I think it’s very concerning what we’re seeing on the world stage right now, and we’re seeing it all over.” During a trip to Myanmar in 2015, Pitzer was shocked at the similarities between statements from supporters of camps in the country and what Donald Trump was saying in his early campaign speeches.

“The bloody statements about Muslims, the militaristic language around it, the identification of immigrants as a threat and Muslims and immigrants both as cultural threats, but also that people were physically in danger so we had to do something came up again and again in both orbits simultaneously,” she says. “But they were, at that point, operating independently of each other. So it is this larger wave, but I’ve found that the language is in use again and again.”

One Long Night is dedicated to exploring the past and present of concentration camps and how their definitions have changed and evolved over time. The first recorded use of the term “concentration camp” in the New York Times didn’t refer to a site of Nazi atrocities or a Russian Gulag. It was in reference to Camp Alger, a Spanish-American War-era site in Northern Virginia where recruits were concentrated before being sent to train or fight elsewhere.

The weight of the term’s current definition compared with its past is part of the reason Pitzer decided to structure One Long Night chronologically. The story starts and ends in Cuba, opening with the roundup of Cuban peasants in the 1890s and closing with detainees at Guantanamo Bay. In between are stories from more than 100 years and six continents.

“I think as a historical text only so many people would be interested in it just for the dry history of it. But it’s the human history that I think is particularly compelling to people,” Pitzer says. “On the one hand it’s a really epic panoramic history but I also telescope down in each chapter to one person’s place in this camp structure and what happens to that person.”

Pitzer explains the concept of concentration camps as a tree with many branches. Its branches reach far apart and change as they grow and age, but they’re all connected to the same roots. Guantanamo Bay isn’t Auschwitz, Auschwitz wasn’t a gulag and the gulags were certainly far from the groups of Cuban peasants behind barbed wire. But they all share the common thread of being extrajudicial detainment of people without trial or conviction.

The details have changed with each new iteration, often because a society was sure they could use camps without being like whoever came before them. In the chapter on the camps of World War I an Austrian man in England hears of plans to intern “enemy aliens,” but isn’t overly suspicious of the policy.

Pitzer writes that, “Cohen-Portheim had heard that Afrikaner women and children had been detained in harsh conditions by the British during the Boer War and that these concentration camps had been seen ‘as a cruel expedient.’ Hoping that the new camps would not resemble their forerunners too closely, he assured himself that ‘at present no doubt internment meant something quite different.’”

Though Cohen-Portheim was correct in his time, it’s in this thinking, Pitzer contends, that some of the danger of history repeating itself lies. Governments and societies think they can improve upon a flawed concept to make it work for them, often to disastrous results. In her research she’s found that the establishment of camps is rarely a decision made in panic and rushed into, and instead a product of dangerous rhetoric about vulnerable groups and manipulation on the part of those in power.

“Somebody has to intentionally create it, and somebody has to intentionally resist it or push back against the arguments that are used to justify it,” Pitzer says. “It’s not going to happen by accident, but, if somebody successfully helps to trigger the things that lead up to it, it’s not going to stop by accident either.”

Those who believe concentration camps to be a thing of the past may find the final chapters of One Long Night to be surprising if not shocking. Examples of concentration camps in Myanmar and a strong argument for the consideration of the US military’s detention center Guantanamo Bay as a concentration camp close out the history, though Pitzer acknowledges that a history in the making cannot truly have an ending.

How that story continues depends on people’s ability to learn from the past, something Pitzer hopes One Long Night can help make easier. While it seems simple to say that concentration camps are bad and should not be used, that moral clarity tends to be more cloudy in practice. Issues of guilt and innocence arise and, just as quickly, are deemed irrelevant. One-time exceptions to the rule of law become longer-term solutions, and longer-term solutions give way to abuses and hidden histories.

Despite the lessons of the past, societies have fallen for the myth of the successful, moral concentration camp over and over again. Pitzer wrote her book partially to try to ensure that people don’t fall for it again.

“I’m not saying there aren’t problems that are hard to solve,” she say. “Societies are faced with terrible reckonings and things where they have to figure out what to do, but understand that this is a temptation that rises again and again and we fall for. It’s Charlie Brown and the football. Don’t fall for it again … You’re going to end up flat on your back and disappointed in yourself, having surrendered to something you should have seen coming.”

‘One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps’ by Andrea Pitzer, available Sept. 19, $30