From the moment Mayor Scott Silverthorne began planning the meth-fueled sex party, something seemed off.

It all started, according to the Fairfax County Police Department’s investigative report, on July 28, 2016. That’s when Silverthorne, using the profile name anotherfundcbttm, received an “oink” from another man, Tony, on the gay hookup website BarebackRT.com.

“What’s Up?” the mayor responded, before asking what Tony was into and if he had any “supply.” Over the following week, he exchanged additional messages with Tony in an effort to obtain methamphetamine and, according to the police report, organize “what he called a gang bang.”

They agreed to meet at the Crowne Plaza hotel in Tysons. Tony would bring his friends Kevin and “big dick nick.” Silverthorne’s buddy would join in as well.

Silverthorne, though, had a problem. The mayor of Fairfax was too broke to buy the drugs himself, so he arranged for his dealer to be at the hotel with a supply that Tony and his friends would purchase. The mayor said he might be able to chip in a couple bucks—he needed only a little.

The more Silverthorne chatted with his new friend, however, the more puzzled he became. Tony’s text messages included LOLs and emojis in awkward places. He “didn’t talk the way other gay guys talk,” Silverthorne says. For example, when the mayor texted that he’d like to shower as soon as they got to the hotel room, he says Tony responded, “Don’t worry, there will be free showers for everyone.” It was a curious thing to say, but Silverthorne wasn’t about to let a few offbeat comments ruin his night: “I was chasing that next high.”

By 7:16 pm on August 4, 2016, most of the group had arrived. Oddly, given the hour, Silverthorne was told that the hotel room wasn’t ready, so he and his friend decided to wait in the Chrysler 300 that Tony’s pal Kevin was driving. As the four piled into the car, Silverthorne asked Tony and Kevin if they were police. The two men laughed. The mayor said, “I’m just really paranoid.”

Inside the Chrysler, Silverthorne grabbed Tony’s crotch and touched Kevin’s groin. “Oh, you’re the bottom,” the mayor said, according to the police report. But first they had to get the drugs, so Tony and Kevin handed Silverthorne $200. The mayor took the cash to the hotel bar, where his dealer was waiting, and bought just under a gram of meth. He went back to the car and handed the drugs to Tony. For a short while, the men chatted. Then, as Silverthorne’s lawyer puts it, “the whole world turned to ninjas.”

Tony and Kevin—undercover cops after all—bolted from the Chrysler. SUVs screeched up. Men in black masks and tactical gear converged.

Don’t move or we’ll tase you!

Don’t move or we’ll tase you!

As Fairfax County police officers handcuffed Silverthorne and drove him to the station, the mayor had a distinct thought: Now it all makes sense.

It takes something pretty spectacular to get Fairfax City in the national news. Although it’s surrounded by an immensely diverse county of more than a million people, the town remains a bedroom community, a place where old high-school classmates bump into each other and everyone goes to the Fourth of July parade. But when the details of Mayor Silverthorne’s arrest went viral, the good folks of Fairfax City found themselves at the center of an international sensation.

“If someone tossed a live hand grenade in the middle of Fairfax,” the local Connection Newspapers reported, “it potentially wouldn’t have caused as much damage or such utter shock.” After all, this was Scott Silverthorne—the homegrown civic star, son of a two-term mayor, veteran of nearly a quarter century of city politics, and beloved champion of the community. Says Sharon Bulova, chair of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors: “People looked at Scott as sort of the face of the city.”

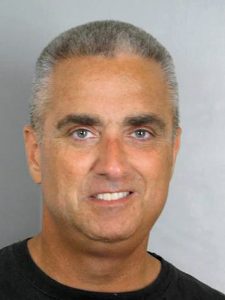

But there was much about Silverthorne that residents never knew. “I called it a secret life,” he says. “A double life.” Now out of jail, he’s opening up about what happened—and about the hidden struggle that brought him to that parking lot in Tysons, put his mug shot in news stories from DC to London, and triggered a suburban political embarrassment that recalls the most famous local scandal in the big city down the road. Silverthorne describes his implosion as “Marion Barry with gay sex thrown in.”

On a Sunday morning in July, Silverthorne takes a seat on a shady bench in Old Town Square. The spot, a half mile from his former desk in the mayor’s office, is his preferred place for a quiet cup of coffee. On the upper tier of the gray-stone plaza, a yoga teacher leads a group through warmup poses; later, children splash through the fountains. The square is the heart of the town, and Silverthorne feels a special connection to it. As a city-council member, he championed creating the public fund that purchased the land, and as mayor, he cut the ribbon on the redeveloped space. He considers the square a “crowning achievement.” Had things turned out differently, it might have been his legacy.

Fairfax City was everything to him. His father, Frederick Silverthorne, was mayor from 1978 to 1982. Scott was raised in a split-level house not far from Old Town Square. After graduating from Radford University in 1988, he went to work for Chuck Robb, Virginia’s Democratic senator. A couple of years later, at just 24, he won a seat on the city council. “Cops often have kids that are cops,” he says. “In my case, I grew up in a political family.”

Friendly and outgoing, Silverthorne was at every groundbreaking and community barbecue, grinning with local powerbrokers and chitchatting with constituents. “He was one of the most popular politicians in Fairfax City,” says Gerry Connolly, the Democratic congressman who represents the area. “He had that local-boy aura. He had political lineage with his dad and was seen as a genuine booster of the city.”

After nine terms, a promotion seemed inevitable. When Silverthorne launched his mayoral campaign in 2012, would-be opponents vanished. “It was like the parting of the seas,” Bulova says. “Folks stood back and supported him.” He took 86 percent of the vote.

Although technically an independent—Fairfax City runs nonpartisan elections—Mayor Silverthorne advanced a liberal agenda. He used taxpayer funds to convert private lands into parks, trails, and other public amenities, such as Old Town Square. He pioneered an initiative to control the city’s growing deer population with surgical sterilization, as opposed to managed hunts. He pushed for a higher-density, more walkable downtown district. He helped a struggling local homeless shelter find a new building to operate from. Meanwhile, he created new public events to bring the community together, such as Rock the Block, a free summer concert series featuring bands, food vendors, and a beer garden. Silverthorne thought of himself as “the mayor of the best small city in America.”

He won reelection in 2014 by nearly 50 points. A local restaurant began offering the Mayor Scott Cheeseburger. To honor his 50th birthday, the city council named November 17, 2015, Mayor R. Scott Silverthorne Day. While delivering the proclamation, Councilmember Jeffrey Greenfield said Silverthorne’s colleagues “have said he was the best politician the city ever had.”

In private, however, the best politician Fairfax City ever had was suffering from the compulsion he’d concealed for more than a decade.

After a brief marriage to a woman in the 1990s, Silverthorne came out as gay to those closest to him. Although he never made his sexuality part of his political identity, friends, colleagues, and fellow civic leaders all knew. “Worst-kept secret in Fairfax,” says Brian Drummond, Silverthorne’s lawyer and longtime friend.

Reflecting on it all, Silverthorne pinpoints where his troubles began. Sometime in the early 2000s, when he was in his mid-thirties, the young pol visited a friend’s home in the Washington area. (He won’t specify the location.) He’d just been through a painful breakup and was brooding when one of the other guests offered him some meth. “This will make you feel better,” the man said.

Up to that point, his only experience with drugs had been a couple puffs of marijuana in college. On that evening, however, it seemed like a way to escape.

He liked it. A lot. Meth produces a euphoric wave that can last up to 16 hours, zapping users with energy and a sense of enhanced intelligence. “Wow, I feel great,” Silverthorne remembers thinking. It also triggered, as he puts it, “a type of sexual energy.” He began regularly using meth at the homes of other men in his social circle—although never, he insists, in Fairfax City. “[Sex] was often involved,” he says, “but not always.”

In the beginning, he might do meth once every couple of months. “Unfortunately,” he says, “the drug begins to take over your life, and you start using more and more frequently. Once a month, then maybe once every three or four weeks. Then once every two or three weeks.”

Most elected offices in Fairfax City are part-time posts with modest stipends. Silverthorne’s day job was as a lobbyist for Capital One and, later, MasterCard. He says he made it work by limiting his drug use to a couple of weekends a month: “I might start on a Friday, like 5 o’clock, 4 o’clock, like you might go get your happy hour, and then I would wrap it up by Saturday night.”

After this round-the-clock partying, he’d sleep all day Sunday, head to his lobbying job on Monday, and be back at City Hall for hearings on Tuesday. It was all meticulously planned: “I knew that if I was going to do this, I couldn’t have a public-speaking engagement the next day.” He carried out this routine, on and off, for nearly 13 years.

After the arrest, the mayor walked to Old Town Square and sat quietly on a bench. Although he knew the world was about to discover his secret, he was consumed by an unexpected feeling: relief.

Over time, Silverthorne started going online to meet men for drugs and sex. The practice put him in dangerous positions. Friends were threatened and robbed; four men he did meth with have died of drug-related complications. He says he saw a counselor and got clean for a couple of years sometime around 2005 but started using again after his father’s death in 2009. He says no one in the local government knew of his addiction: “I just suppressed this side [of my life] and kept it hidden from people. Because you’re embarrassed. You don’t want people to know you have a problem.”

Silverthorne claims his addiction had no impact on his performance as mayor: “Was I tired perhaps on a Tuesday if I had been partying [the weekend] before? Possibly.”

His finances were the first thing to go. As a lobbyist, he enjoyed a lucrative salary. In addition to his five-bedroom house in Fairfax City, he bought a vacation condo in Palm Springs. But in 2009, he gave up lobbying, and his new job in executive recruiting didn’t pay as well. He says he never downsized his lifestyle. Unpaid bills piled up. In 2013, the vacation condo went into foreclosure.

The direct expense of the drugs wasn’t the problem. Silverthorne says he used only about $120 worth of meth a month, and when cash got tight, someone was always willing to cover him. Rather, the meth made his financial crunch feel less urgent: “I just stuck my head in the sand.” In 2015, after he was laid off from his job as recruiting director for the National Association of Manufacturers—he says it wasn’t drug-related—the bank foreclosed on his Fairfax City house. Silverthorne moved in with a friend. When he filed for bankruptcy later that fall, he asked the court to waive the filing fee because his only income was a $450 monthly mayoral stipend.

Then a whole new crisis emerged. After finding a lump on his neck, Silverthorne was diagnosed with a form of cancer known as squamous-cell carcinoma. While his prognosis was excellent, the chemotherapy and radiation left him nauseated and fatigued. Nevertheless, he remained in office. Being mayor of Fairfax City was “central to his identity,” says Tom Davis, the former Republican congressman from the area. Davis recalls speaking to Silverthorne during this period of turmoil. “The only thing going good for me in my life,” the mayor told him, “is the politics.”

Eventually, Silverthorne’s private troubles seeped into his public life. During the 2016 mayoral race, supporters of his conservative challenger, Tom Ammazzalorso, firebombed the typically cordial proceedings by releasing a two-page pamphlet detailing Silverthorne’s home foreclosures, job losses, credit-card debts, and personal bankruptcy. “After years of disastrous financial decisions,” the pamphlet read, “would you hire Scott to manage our City finances?” (In fact, Moody’s Investors Services reiterated the city’s AAA Bond rating that very September.)

The attack appalled the local political establishment, but it proved effective. Unlike his previous routs, Silverthorne won the election by a more modest margin, taking 58 percent of the vote to Ammazzalorso’s 42. “I was slipping,” he says. “I think drugs had something to do with it. I just wasn’t as sharp. I wasn’t on top of my game.”

Still, as he was sworn in for his third term, the public had no idea that their mayor was a meth addict.

Less than three months after Silverthorne’s reelection, detectives in the Fairfax County Police Department received a tip from a citizen alleging that the mayor was using BarebackRT.com “to meet men and possibly exchange methamphetamine for sexual encounters,” according to assistant commonwealth’s attorney Kathleen Bilton’s later court testimony. Based on this information, undercover officers visited the site and created a profile designed to appeal to the mayor. “We knew what he wanted sexually,” says Captain Jack Hardin of the department’s organized-crime-and-narcotics division.

On July 28, 2016, a detective sent the “oink” to Silverthorne’s profile, and the two began planning the hotel party. Seven days later, the mayor was arrested.

Silverthorne was charged with felony distribution of meth and misdemeanor possession of drug paraphernalia. Police arrested the two dealers but opted not to charge the mayor’s friend who was also in the vehicle. At the station, Silverthorne fessed up. According to Bilton’s testimony, he even admitted that, after receiving the $200 from the undercover cops, he’d bought only $140 worth of meth from his dealer and used the remaining $60 to settle a debt. (Silverthorne disputes this.) As the interview concluded, Silverthorne says an officer asked him if he wanted to disclose anything else.

“No,” he replied, “I don’t think so.”

“Well,” the officer said, “how about if you hold elected office?”

“I think you already know the answer.”

Silverthorne was released around 11 that evening. As he prepared to leave the station, he asked the officers if they could give him a little time in the morning before they went public. It was out of their control, they said. He headed to Old Town Square, his crowning achievement, and took a seat on a bench. For about an hour, he sat alone in the darkness. Although he knew the world was about to discover his secret, he was consumed by an unexpected feeling: relief. Okay, he thought, now I can deal with my problem.

Early the following morning, as word began to spread, he called his lawyer, transferred his mayoral responsibilities to the senior-most city-council member (Silverthorne resigned days later), and disappeared to his niece’s house outside the city. Meanwhile, satellite trucks arrived at City Hall, and reporters knocked on doors in his neighborhood.

At 9:30 am, Captain Hardin stood be-fore a bank of TV news cameras in Fairfax County police headquarters and provided the details of Silverthorne’s arrest. Describing the tip that had sparked the investigation, Hardin said, “It was alleged that the mayor was exchanging methamphetamine for, in exchange for sex.” This meth-for-sex claim made the story a bona fide sensation.

“I handled more media inquiries in 48 hours than the other 27 [years of my career] combined,” says Silverthorne’s lawyer, Brian Drummond. “I mean by far. Dr. Phil’s people called. Inside Edition called. Every major news organization in the world called. Calls from overseas. Calls from the gay newspapers.”

Today, the ex-mayor maintains there had never been any quid pro quo. He had simply helped arrange for consenting adults to get together. “Let’s say I’m having a Super Bowl party and I say, ‘You bring the beer,’ ” Drummond explains. “Same concept. We’re all going to share that beer, but you’re not trading that beer to be able to watch the Super Bowl at my house. It was never like that.”

In addition, Drummond argues that the police specifically targeted the mayor on account of his position: “This was a setup from on high.” Silverthorne says he has great respect for the individual police officers who took part in his arrest, but he blames the Fairfax County Police Department for sensationalizing his case. At the press conference, the police “were beating their chests like they had arrested some big drug kingpin.” It was all part, he says, of a public-relations effort to revive the department’s image from the scandal surrounding a county police officer who had recently pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter for killing an unarmed man. “They were looking for some quick wins and some victories,” Silverthorne says. “I happened to give them that opportunity.”

Captain Hardin says these factors played no role in the department’s handling of the case. “I’ve lived here my whole life, and I never knew [Silverthorne’s] name, I never saw his face,” he says. (Fairfax County’s government is independent of Fairfax City.) “This case would have been investigated regardless if it was the mayor or if it was some guy working at Giant.” The department says it carries out 10 to 15 similar operations per week.

On March 13, Silverthorne arrived at a Fairfax County Courthouse for what he thought would be a routine arraignment hearing. In addition to the public shame, he was facing serious legal consequences. The distribution charge carried a maximum 40 years in prison and a $500,000 fine. He pleaded guilty anyway, because sentencing guidelines call for probation for someone with a clean record, among other factors. The courtroom was packed with friends, family, city officials, and local politicos, and everyone assumed Silverthorne would remain free until the sentencing. “He is no danger to the community,” Drummond argued. “I certainly see no reason for him to be incarcerated between now and sentencing.”

The judge disagreed. The former mayor was given a green jumpsuit and escorted to a jail cell 1,000 yards from his old office in City Hall.

The next three months were rough. Because of his former position, Silverthorne was placed in protective custody, and for the first week of his incarceration that meant solitary confinement.

“No physical contact with humans,” he recalls. “I got to use the phone twice that week. No natural light. No reading material. No writing material. I was only allowed to shower twice in the week.”

When Drummond complained, Silverthorne was moved to a different part of the jail. Although he still slept in a cramped cell, his new living quarters included a common area with a TV, telephone access, showers, and toilets. He shared the space with two other inmates—“law-enforcement guys”—with whom he clicked. They called him “The Mayor.”

Silverthorne describes his implosion as “Marion Barry with gay sex thrown in.”

He passed the time by reading John Grisham and David Baldacci novels and chatting with local government officials who stopped by to visit.

When Silverthorne showed up at his sentencing hearing—20 pounds heavier thanks to a starchy jailhouse diet and commissary potato chips—a who’s who of Northern Virginia civic life urged leniency. The new mayor, the city manager, five city-council members, two ex-mayors, the heads of local nonprofits, a state senator, a state delegate, a reporter for the local Connection Newspapers, and the president of George Mason University wrote letters on his behalf.

“The actions that bring Scott before you are the result of his personal demons,” 12 current and former local politicians said in a joint letter, “demons he has struggled with and which finally took their toll.”

At the end of the hearing, the judge let Silverthorne address the court. “My arrest and public humiliation, in retrospect, was probably the best thing that ever happened to me,” he said. “It forced me to accept a fact that I was unwilling to accept at that point and probably can be viewed as a blessing in disguise. I need you to know, Your Honor, and the public that’s here—this is the first time I’ve ever said this publicly—that I am an addict.”

Judge Grace Carroll asked Silverthorne to turn and face his supporters as she announced his sentence. Seeing his friends and family choked up the former mayor. The judge sentenced him to time served and 200 hours of community service. Silverthorne was free to go.

As he walked out of the jail, he addressed a group of reporters. “This is my hometown,” he told WTOP. “I served it faithfully for about 25 years, and I’m going to miss it. I’m going to miss it every day.”

Only five months out of jail, Silverthorne is still adjusting to his new life as a convicted felon and recovering addict. He spent an entire day at the Department of Motor Vehicles in August trying to get a new driver’s license after the court revoked his original one. The process required him to retake the written and road portions of the driver’s test. He passed both.

Despite the regular reminders of his fall, he’s able to find some levity in morbid humor. Asked about the passage in the police report where he’s described as grabbing the undercover officers’ crotches, he deadpans that he was “disappointed” in what he found.

Still, remaining sober is his top priority. Shortly after his arrest, he spent a month in a residential treatment center near Minneapolis that specializes in substance abuse within the gay community. While there, he learned that most addicts use drugs to cope with some sort of underlying burden, and he believes his was a subconscious shame about his sexual orientation. It was also during this time that Silverthorne discovered just how widely his legend had circulated. Though the rehab facility was nearly 1,000 miles from Fairfax City, a wide-eyed fellow addict approached him at one point.

“You’re Scott Silverthorne,” the man said. “I read about you in the Chicago Tribune.”

Today he attends Narcotics Anonymous meetings several times a week, lives with a friend in Fairfax City, and commutes to work at a hardware store in Bethesda. While many locals remain angry at him for the embarrassment he caused, he says he’s also found great support: “When I walk down the street, people will pull over their cars on the highway and get out and hug me. It’s remarkable.”

Nevertheless, Silverthorne isn’t sure he’ll remain in the city or, for that matter, what career path he might pursue from here. (He hints at the possibility of a book or movie about his life but won’t provide details.) He has no plans, he insists, to return to politics—as a convicted felon, he’s ineligible to run for office in Virginia anyway.

“I want people to know that I am remorseful, that I’m contrite,” he says. “I still feel, every day, terrible for what I put the community through. I feel terrible for what I put my family through. But I also recognize that I’m one lucky guy, and that, you know, people are rooting for me. And hopefully I’m going to bounce back.”

This article appears in the November 2017 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)