The scenario would go like this. On Tuesday, November 6, Americans tune to television sets and radio broadcasts, unlock their phones and keep an eye on their desktop screens, all waiting for the same thing: A definitive account of who has won what in the midterm elections. Throughout the night, election numbers shoot across their screens—live, preliminary return data pumped in from congressional and Senate races across the country, and key gubernatorial races, too. Then, around 10 PM EST, CNN anchors announce the network’s call: The Democrats have taken control of the House, winning 31 of the necessary 24 seats to successfully wrest control from Republicans. On camera, Van Jones and Anderson Cooper waste no time as they begin discussing the implications of the victory and how the midterm results have placed the Trump presidency in a new chapter of turmoil.

But there’s a problem. Fox News analysts have just announced the opposite result: In an extraordinary turn of events, Republicans have managed to hang on to their majority by a single seat, retaining control of the House. It’s a major political upset, says Bret Baier, and a replay of Trump’s surprise victory in 2016. And yet for clients of the newswire Reuters, the results are simply opaque—with political analysts there reporting that control of the House, and several nail-biter gubernatorial and Senate races, still remain too close to call.

The next morning, as the country tries to sort through the crisis, the President pours on accelerant—sprinting toward an obvious opportunity to delegitimize the incoming House Democrats, who may well alter the fate of his presidency. This proves that the election is rigged, Trump bays to a crowd of raucous supporters. And what did CNN do, when the results showed Republicans winning? The lying media rigged the numbers!

It’s a nauseating scenario. But is it possible?

Several current and former members of the intelligence community, as well as civilian officials in the Obama White House, suggested that it is—at least in theory. The idiosyncratic nature of American elections is at the heart of their concerns: Namely, that the numbers that appear on our various screens throughout election night are, in a way, an illusion.

In 2018, three companies will be responsible for collecting election results as fast and accurately as possible—the first time since 1964 that the tallies have been so fiercely contested, experts tell Washingtonian—and feeding them to their respective clients, like CNN, Reuters, and Fox News, each of which relies on different purveyors of data. And as people affiliated with these efforts themselves acknowledge, these bottlenecks of election data would, hypothetically, make an interesting target to adversaries whose aim is to sow discord.

“It was a concern that we had running up to 2016,” says Lisa Monaco, who served as Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism. “We were very concerned about a whole range of worst-case scenarios,” she says, a list that included physical attacks at polling sites to meddling in voter registration. As part of that list, “We were worried about efforts to influence and sow misinformation in the reporting and early results,” Monaco said. “We were worried about that.”

Monaco’s highlighting of the so-called reportability system was seconded by others in the administration and in the field of cybersecurity. And in the run-up to the 2016 election, the reason for their concern—a hack aimed at preliminary voting results—was simple: They’d seen it happen before.

In May 2014, during the night of the Ukrainian presidential election, a security firm discovered malware on the servers of Ukraine’s Central Election Commission. Kremlin-affiliated hackers had designed a web page, meant to mimic how the election results are displayed, that would have announced a false winner—far-right candidate Dmytro Yarosh—and timed the fake results to display when the polls closed. Discovering the malware just in time, security engineers unplugged the server, which prevented the attack from succeeding—but not before some Russian media, unaware the plot had been foiled, reported that Yarosh had won the election anyway and, citing the Commission website, broadcast the fake graphic on live television. Thanks to the security officials’ well-timed intervention, what might have been a calamity was largely avoided. But the intent of the attack—to sow public doubt into the legitimacy of the night’s victor, Petro Poroshenko—was clear, as well as the Kremlin’s involvement.

In 2016, administration officials faced an obvious question: Could the Ukrainian-style attack, one that temporarily announces a false winner in some elections, happen here?

Most state and local election officials say no, and for good measure. Ukraine’s commission calls outcomes for all the country’s races. The United States has a system unlike any on earth, with virtually no federal involvement, much less a single, national election office that could host a server ripe for target (or unplugging) on election night. The county-based election system that holds throughout most of the country means that results are reported by more than three thousand jurisdictions, usually to each state’s Secretary of State. To hack the preliminary results of an election here, attackers would be required to target thousands of counties, townships and boroughs—a practically impossible feat.

Except, as officials learned in 2016, for one problem: We may not have a central bureau. But we do have a private sector equivalent. In 1848, a small company took advantage of a new technology, the telegraph, to expedite its tallying of American elections. For more than 150 years, it perfected the technique and brought it into the modern era, and until recently offered the singular method for how the country learns the unofficial national tallies that declare winners and losers on election night. Today, we know it as the Associated Press.

Between 2003 and 2016, a division affiliated with the AP, called AP Elections—entirely separate from its journalistic arm—held a virtual monopoly on the national effort to collect and tally the unofficial vote totals we see on election night. Their efforts were marshaled on behalf of a consortium of media outlets, called the National Election Pool (which also included exit polling, led by another firm, called Edison Research). In 2016, nearly every large-scale media outlet relied at least in part on AP Elections figures—election-night data displayed by the New York Times, Washington Post, and CNN—as well as outlets serving regional media markets and local news. While AP Elections didn’t provide an official figure for the number of clients it serves, an AP spokesperson told Politico last year that “thousands” of clients “rely on AP to count the vote and call races.” The enormous reach of AP Elections data rendered it a logical, if hypothetical, target for manipulation, or so security experts feared: On the night of the 2004 presidential election, according to one AP account, the AP Elections figures attracted a worldwide audience estimated at more than a billion.

The AP’s undertaking is vast, and its record is sterling: Of 4,653 elections in 2012, AP called only six incorrectly, BuzzFeed reported. But not much is publicly known about the specifics of the AP’s tallying operation.

The AP is, understandably, disinclined to discuss exactly how its system works, or its security posture. A spokesperson for the AP declined to elaborate on either, and pointed Washingtonian to several public FAQs. (The AP also provided a short statement: “It has long been the policy of The Associated Press to refrain from commenting publicly about our security measures in place in the U.S. and around the world. Given the increased interest in the midterm elections, we would add that AP has been working diligently to ensure that vote counts will be gathered, vetted and delivered to our many customers on Nov. 6.”)

A speech given in 2014 by AP Elections Director of Election Tabulations and Research Don Rehill sheds some light on the process. According to notes from Rehill’s speech, which a conference attendee shared with Washingtonian, 13 election-tallying coordinators across the country oversaw more than a thousand staffers at the company’s vote tabulation centers. (In a later FAQ, the number was 800.) To do it, the AP relies on its national corps of stringers, 4,000 of whom will be stationed in counties and precincts across the country on Tuesday to physically monitor locations of vote counting (like a county clerk or registrar’s office) and will often manually phone them into one of the vote tabulating centers.

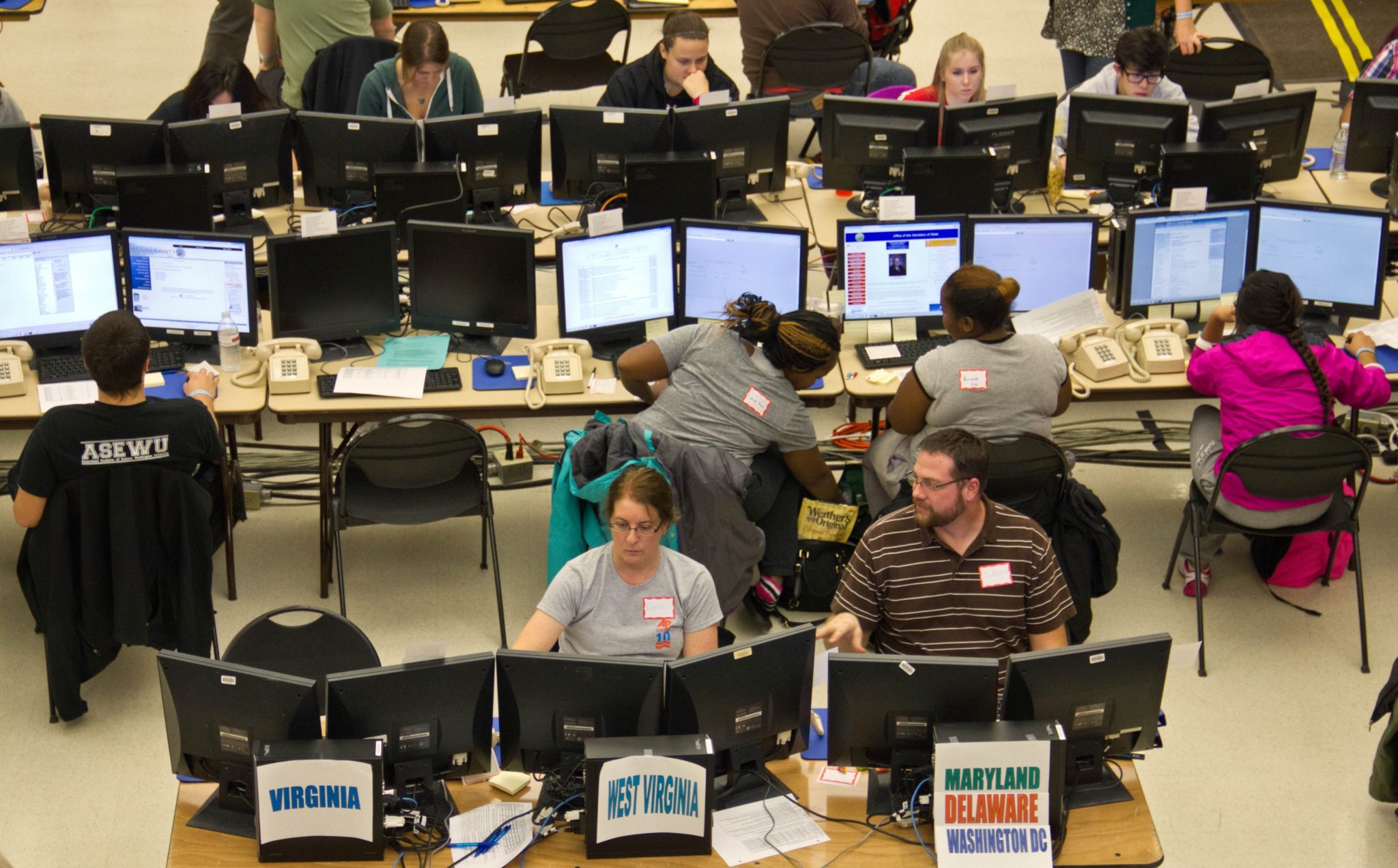

AP Elections hosts several of these vote counting centers—in 2012, there were reportedly four—large congregations of desk-bound staff who tally the results of a distinct set of states. Since 2000, one of these vote tabulation centers has been located in the campus field house at Eastern Washington University, according to Steve Blewett, the longtime faculty coordinator of the center, and an emeritus professor of journalism at the university. There, a corps of 300 college students, typically paid $12.50 an hour, will man the rows of tables and phones this year, answering phone calls from stringers around the country (and monitoring other forms of online data, as counties increasingly make their precinct tallies available online). Before each election, AP Elections staff unload a semi packed with company-owned computer equipment. (An AP spokesperson called parts of Blewett’s and Rehill’s accounts “incorrect,” but wouldn’t specify further.)

As late as 2012, the operation at EWU was reported to be the largest of the AP Elections tabulation centers. This year, Blewett says, the tabulation center in the field house is slotted to call 13 states—Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, Minnesota, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, Idaho, Nevada, and California—jurisdictions where Cook Political Report has identified 38 competitive House races, two close Senate races, and five gubernatorial races that Cook rates as “toss-ups.”

Rather than target the individual counties of these states—where election officials rely on a number of backup procedures—it would be easier, some cybersecurity researchers suggested, to target the reporting effort and meddle with data figures there. If an attacker were sufficiently sophisticated, the list of options could be wide-ranging, from crashing individual computers at vote counting centers, to implanting malware on the software that communicates between the data centers and news outlets. “If the goal is to create at least the appearance of irregularities in the official vote count, then this is one of the tactics someone might try,” says one former Obama administration official close to the effort to secure election infrastructure. “It’s an attack where you don’t worry so much about the substance. You worry about the psychological effect of it.”

Since 2016, the federal government and AP Elections have taken at least one key step to securing the national reportability system. After the Department of Homeland Security designated elections as “critical infrastructure”—a special category for civilian sectors that receive advanced federal security protection—it invited AP Elections to serve on the DHS Sector Coordinating Council. The council includes other private sector entities deemed crucial to administering elections and convenes throughout the year to discuss security threats and private-sector goals. According to DHS, eight private companies are receiving government-funded cyber hygiene scans, while others have undergone risk-and-vulnerability assessments, an on-site evaluation that includes penetration tests and close examination of company networks. (DHS did not identify whether AP Elections was one of the companies receiving these services.)

It’s an open debate in the cybersecurity community whether these measures, which haven’t always thwarted the most determined state-backed attackers, will be enough. Without visibility into the AP’s proprietary software and API, which communicates data between the AP and its client media outlets, there’s no reason to suspect, or any way to know, whether there are security vulnerabilities of the glaring kind sometimes attributed to election technology vendors. AP’s comments did not include answers to questions from Washingtonian about AP Elections’s cybersecurity posture—such as whether the division has a chief information security officer, consults with a security firm, or is receiving protective services from DHS.

Blewett says security at the field house “is very rigorous,” adding, “nobody can just wander in off the street and wander around and see what’s going on there.” Blewett also said he wasn’t aware of any effort to subject student and faculty staff, which are under his purview, to background checks—a recommendation advanced by the Belfer Center at Harvard for improving election security. Other researchers who saw photographs of the field house voting center raised questions about the IT configuration visible there: Matt Bernhard, an election security researcher at the University of Michigan, wanted to know which computers were networked and which were “air gapped,” or isolated from the internet; the security protocol for the machines when stored between elections; the use of two-factor authentication; and whether the models allowed for USB or CD-ROM inputs, methods that hackers have used for on-site delivery of malware in the past. (Blewett couldn’t speak to those aspects of AP Elections’s security measures, but did mention that he believes the computers have USB ports.)

These questions are far away from spelling doom, of course. But they present an important new line of inquiry, even as an intellectual exercise, that has taken on new importance in the era of election meddling. In this way, the field house offers a symbol of the kind of civic traditions and niceties that are often being reevaluated in the aftermath of 2016. “It’s in the interest of everyone to make sure that we have as robust a reporting system [as possible], and defend it in the right way,” said Michael Daniel, who served as the White House cybersecurity coordinator in 2016 and is now the president and CEO of the Cyber Threat Alliance. “And we should be undertaking those steps.”

Both Blewett and Rehill, in his speech, outlined a system of deliberate failsafes when it comes to inputs. “They have some checks and balances built into their computer, where if numbers don’t agree with the last reporting sequence, automatically, there are alerts that come up,” Blewett says. An FAQ published by the AP describes a process of “failover testing,” and the ability for its national system to “swing over to an alternate site” should something go wrong.

But it’s the distribution effort—when the numbers are beamed into newsrooms across the country—that give some cybersecurity experts pause. Just as they have imagined sophisticated malware on election machines, which could throw a sequenced number of votes to particular candidates, or activate under specified preconditions, cybersecurity researchers described the same general principle in preliminary reporting: Look-alike numbers beamed out for key races, or, if the attackers were favorable to chaos, crafting wildly different data for each client—with the intended targeted not an election machine but your television screen.

More than anything, it’s the current partisan environment—and the dramatic stakes of the midterms for both parties—that could provide dry tinder for the spark of even momentary confusion about the results. According to research by MIT professor Charles Stewart III, one of the best predictors of whether a voter believes the elections were administered competently, or if they were tampered with, is whether their candidate or party won or lost the election. “It’s the combination of [an attack] like this, along with disinformation, or starting a conspiracy theory,” said the former Obama administration official, that might prompt some voters to “end up questioning the legitimacy of the election.”

Since the last midterms, yet another development has altered the security landscape: AP Elections now has robust competition. In 2016, a startup outfit, called Decision Desk HQ, began tallying races for Reuters; it has since expanded its operation, winning clients at BuzzFeed, Vox, and the New Yorker. Beginning last year, Edison Research launched its own vote-tallying operation, whose clients now include the news operations of CBS, NBC, and ABC—plus CNN. (Fox News will continue to display its figures from AP.)

Data analysts in both organizations spoke frankly about their awareness of the threat. “We take this seriously from a number of angles,” says Drew McCoy, a data specialist at Decision Desk HQ, who added that the threat of hacking is “obviously something that our technology team is aware of.” McCoy continues: “We understand the concerns around election-oriented companies. This is stuff that governments deal with. We saw what happened with OPM and the credit rating agencies”—references to previous successful attacks—“and there’s nobody that’s immune to this.”

Joe Lenski, the co-founder and executive vice president of Edison Research, told me, “We’ve taken security measures since 2016,” adding that, though he couldn’t describe specific measures, “the main way to deal with it is monitoring and redundancy. So, if any line of communication is compromised, it’s disconnected and other redundant lines replace that.” Lenski wouldn’t say whether his company was one of the eight receiving DHS protective services, but did confirm that DHS had contacted Edison’s clients in advance of the 2016 election, describing the conversations as “basically due diligence.” McCoy says Decision Desk HQ hasn’t been contacted by DHS.

(It’s unclear why Edison and Decision Desk HQ aren’t represented on the DHS Sector Coordinating Council, although one reason may be that AP Elections has many more clients. A spokesperson for DHS couldn’t be reached for comment.)

Not everyone in the elections community ranks an attack on the reporting system as a top threat. Judd Choate, the director of elections in Colorado, whose preparedness measures rank among the most sophisticated in the country, was unfazed. “As a practical matter, there is a failover in virtually every state—such as our state results—which are completely divorced from the AP,” said Choate, who described the contingency plans for circulating election night data should something go haywire. In August, when the results-reporting website failed to load during a primary election in Dane County, Wisconsin, the clerk cooked up an innovative solution: He took out his phone, snapped a picture, and posted the results to Facebook. “[The] concern about the AP, I think, is sound,” Choate went on, but thought that if the numbers ever looked askew on election night, media outlets simply “would begin to doubt the AP results, and they would start relying on state results.”

Others think the concern misses the mark entirely. In an email, Joseph Lorenzo Hall, chief technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology in DC, writes, “I’m not too worried about people freaking out if the AP gets owned.” Instead, he said, the lessons from the reporting system architecture are more to do with a culture obsessed with instant results: “A better story,” Hall wrote, “would be to talk about the burden that our collective obsession with getting numbers quickly poses to election officials.”

In fact, it’s this cultural component that raises a far more interesting question: Not whether the reporting architecture gets hacked—but what happens if it doesn’t. The midterms of 2018 will hold a unique distinction for data wonks: The first time since the primaries of 1964—when television networks and wire services last competed openly with one another for vote tallies—that three separate, competitive entities will be churning through national data, and racing to feed it to media outlets as accurately and quickly as possible.

This live competition, which will play out on screens nationwide come Tuesday, may clash with our cultural expectation about the meaning of results and demand a newly critical mindset from viewers about where, exactly, their data is coming from. “Now there are three companies doing this—and on the one hand, that may create some safety, because it’s not a single point failure. On the other hand,” McCoy said, “people are going to have different numbers. And viewers just tuning in, and flipping back and forth watching Twitter, really need to know that.”

As the night progresses, the three entities will often be counting different precincts at different times. The chances of seeing tally numbers that differ between media outlets, McCoy predicted, will be inevitable—the very scourge of “public confusion” that the original vote-tallying cooperative, called Network Election Service, was designed to avert, as the New York Times reported in 1964.

“We all start at zero, and we all end the night at the same point. It’s in the middle,” said McCoy, “that there’s going to be variance.”

That means the threat to public confidence could be domestic as well as foreign—only heightening the need for reporting entities to secure their networks and systems, and educate the public about them—especially as 2020 approaches. Until then, says Daniel, the former White House cybersecurity coordinator, the reporting agencies should continue to take the cyber threat seriously—and accept as much help as they can reasonably get.

“It’s a very complicated area—almost no organization can really do it well on its own,” says Daniel. “When an organization gives you a very quick, ‘We got this’ response”—Daniel chuckles nervously—“that’s when my antenna twitches.”