On a December morning in 2016, Julian Raven was digging around in his basement in upstate New York when his phone buzzed to life. It was a DC number, for the National Portrait Gallery.

It had been three weeks since Donald Trump’s victory; seven weeks remained before the inauguration. Raven made his living partly as a painter—selling Pollock knockoffs, mostly, for suburban living rooms, but lately he’d taken up portraiture. His artwork tended to leave little to the imagination. One recent portrait was dedicated to a victim of an ISIS beheading: a seven-foot-tall, decapitated, smiling head.

Ever since 2015, however, Raven’s life had been consumed by what he’d come to consider his magnum opus: a commemoration of Trump, his spiritual and political hero. It was a gargantuan acrylic shrine—16 feet long, 8 feet tall, 250 pounds. Raven had decided the painting should hang in the Smithsonian. By tradition, the Portrait Gallery displayed an exhibit for the incoming President during the inauguration. Raven had typed up an application and had it e-mailed to the office of the director.

Perhaps the best introduction to Raven is the one the Portrait Gallery got when it plucked his proposal from the printer. The 24-page Word document is an eruption of frenzied prose. Whoever wrote it possessed a penchant for run-on sentences and recursive points, spooled out with an episodic zeal that took the antic tone of an internet ad. One page contained a blaze of exclamation points.

Raven, a conservative evangelical, identified himself as “the artist who painted the prophetic, symbolic, patriotic, and historic Trump portrait/painting.” Even in miniature on the page, the artwork was startling: In the east hovered an ovoid, emerald globe, irradiated in celestial white light; at center, a screaming eagle zooming through space, clutching at an American flag that appeared to unfurl forever into the galaxy. Dominating half the canvas, dwarfing all of this, sat the hulking cranium of Donald Trump. Raven called it “Unafraid And Unashamed.”

To a casual viewer, or a liberally minded one, the portrait could resemble something peeled from a cinder-block wall of the Cominform, feting the exploits of Comrade Tito. Raven, naturally, saw it differently.

The application explained everything. It began with the Vision, which seized Raven in his studio during 2015: an eagle swooping low to save a fallen flag. Then Raven’s 13-year-old daughter mentioned offhand something about Trump and eagles, eerily. Finally, he chanced upon a CNN video of Trump, mugging for the camera with a live eagle. That did it. “I was stunned!” Raven wrote. (Also: “I nearly fell off my chair!”; “I felt like a car had hit me”; and “WOW! WOW! WOW!”)

His missive went on to describe a number of increasingly improbable events: driving the painting across the US, marquee treatment at GOP functions, a fortuitous Trump Tower meeting. The artist had painted “a picture of the future,” the application stated; with Trump’s victory, “the prophecy is fulfilled.”

Despite its screwball orientation, though, the soul of the application was considerate: “I respectfully submit my request” to have the portrait hang in Washington, he concluded. Raven dreamed of a trip to the capital—perhaps even an unveiling ceremony. He felt good about his odds. Until the phone rang.

“What’s she doing calling me?” He thought.

A delicate voice in an Australian accent introduced herself as the museum’s director, Kim Sajet (pronounced “sigh-yet”). Raven was shocked; his application had reached Sajet only the day before. If anything, he’d been expecting a form letter.

“Are you the artist who painted the eagle with the flag in it?” Raven remembers Sajet saying.

“That’s me,” Raven said.

“I’m afraid it’s too big,” Sajet replied. Raven pushed back—size, he pointed out, is not a criterion at the Portrait Gallery. After some back-and-forth, Sajet conceded the point. Then she changed tack.

“The painting isn’t taken from life,” she said—meaning the rendering was adapted from Trump’s Twitter photo, not a proper sitting. Raven parried that Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” poster depicting Barack Obama, which the museum had hung during the 2009 inauguration, was also taken from a photo.

The back-and-forth persisted, with Raven falling into a red-hot argument. Yet underneath Raven’s defiance was puzzlement. This is the National Portrait Gallery director, he thought. What’s she doing calling me?

“It’s too pro-Trump,” Sajet said, later adding, “It’s too political.”

“Too pro-Trump?” Raven replied. “It’s an inauguration. Of course it’s pro-Trump!”

Then came the coup de grâce. “I know this is hard, and no artist ever wants to hear this,” Raven heard Sajet say somberly, “but the painting is no good.”

Raven tried to launch more objections. Sajet was through. “I am the director of the National Portrait Gallery,” she said, according to Raven. “Your application will go no further. You can appeal my decision all you want.” After nearly 12 minutes, the call was over. (The Portrait Gallery would not comment on the conversation.)

Raven sat in silence and considered what had just happened. After some time, one notion became clearer than the rest: That’s the worst thing she could have said to me. You said that to the wrong person.

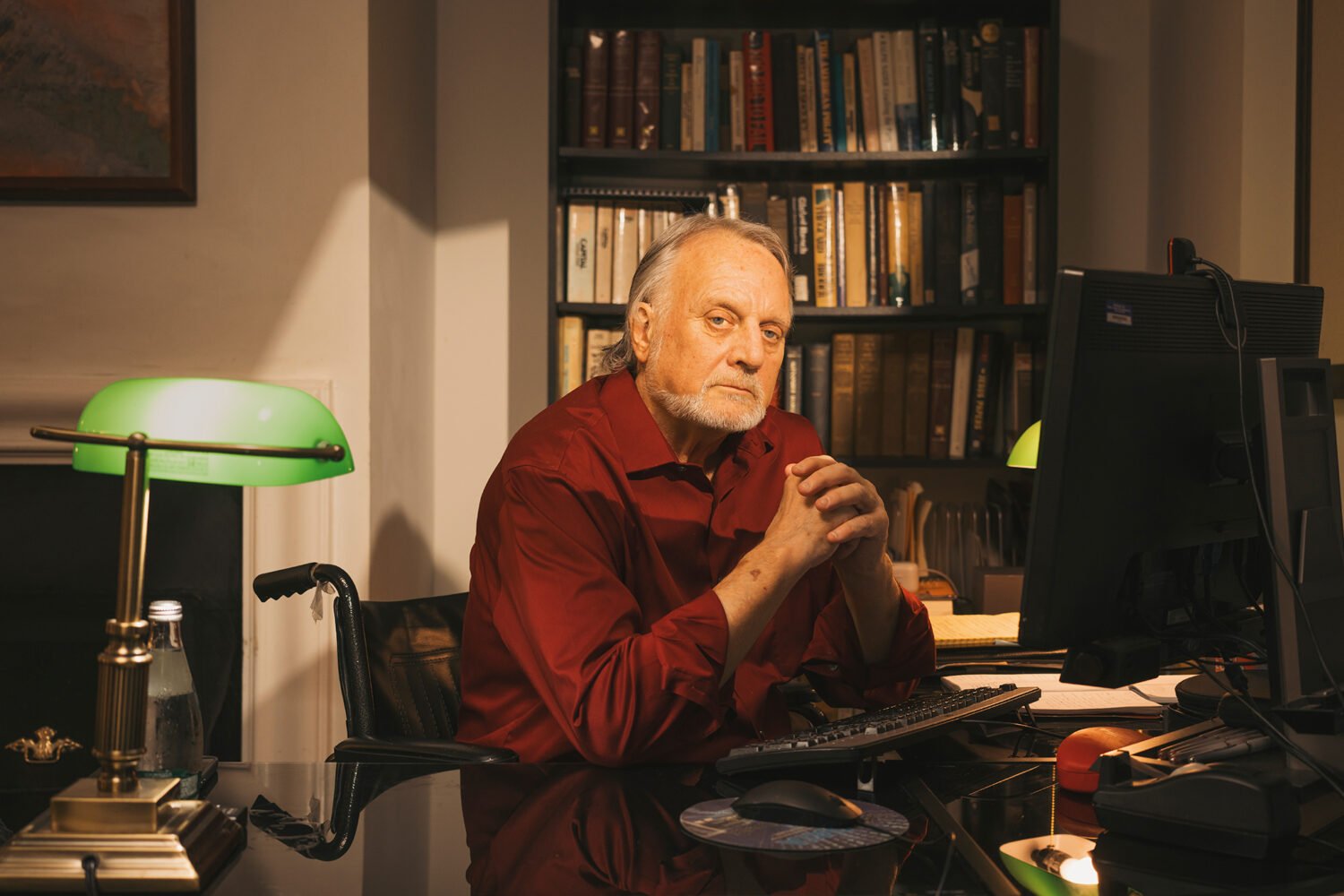

When he recounts his life story, which he does to anyone who will listen, Julian Raven likes to present as a character in a novel. Born in England, raised in Spain, he attended art school briefly in London. In 1992, he became a born-again Christian. Four years later, during a sojourn to the United States, he met his future wife. They settled in Elmira, New York, near Ithaca. He took to woodwork, restoring cabinetry and other household furniture. Mostly, he identified as a pedestrian minister, passing weekends with his family at a local park where they performed Christian hymns for the public. He played the bongos.

Raven, who is 48, towers well over six feet, a bear of a man with sun-bleached hair and a crop of white beard. He’s garrulous and agreeable, laughing often and never unkindly, with billowing chuckles that detonate into booming, wet guffaws. People often stare. When we first met this spring, he described a pair of reporters who encountered the painting. “The two of them just stood there, like stuffed animals—stiff as boards! They wouldn’t interact with me!” He tipped his head back and bellowed like a seal. “It was too positive for Trump!”

After the Vision, Raven spent that summer in a fugue. He sometimes painted 15 hours a day, frolicking shirtless around his studio to the thrum of classic rock, wearing his acrylic-drenched smock around his waist like a batik sarong. Some nights, after a taxing day, he slept beside the canvas.

From the moment the work was unveiled, Raven was swept along by events. In October that year, he traveled to Trump Tower unannounced. A campaign staffer politely accepted a miniature. A few weeks later, Raven tried the stunt again. This time, he rolled through the gold-plated doors wearing a dark suit jacket with matching pants over a starched, onyx-black shirt.

Stooped in the lobby was Michael Cohen, Trump’s now-disgraced fixer, huddling beside a man Raven recognized as Darrell Scott, a black megachurch pastor from Ohio. Raven bounded over with his hand outstretched. Scott and Cohen studied him hurriedly. Finally, Scott said, “You’re late.” Whether a case of mistaken identity or beguiled by Raven’s charm, Scott beckoned Raven to the elevator: “Come with me.”

Trump, it turned out, was scheduled to host a gathering to discuss issues affecting African American churches. Minutes later, Raven was standing in a conference room beside 50 pastors of color. Trump appeared in the door. “I brought my Bible!” he declared, then took a seat beside a dumbstruck Raven. When the roundtable ended, Raven lunged for him and pumped his hand, hyping the portrait and bathing him in praise. It was sealed. The painting hung in campaign headquarters before the end of the week. What’s more, Raven had finally met his hero. At a black pastors’ meeting.

It was, of course, the ultimate sign. Raven rented a truck, which he would plaster with a blowup of the portrait, bade goodbye to his family, and struck off for Iowa. The campaign, he says, seemed wary of the painting. This did not apply to Eric Trump, who spotted the truck after a rally and demanded a photo for Instagram. Raven was invited to the Republican National Convention, where he sat with the New York delegation and watched from the front row as his painting flashed across the 30-foot jumbotron.

Then Trump’s win. As Raven considered what to do next, a friend mentioned the Smithsonian. “I didn’t even know what the Smithsonian fully was!” he confesses. “I was like, bingo! That’s it!”—the next step along a path shimmered by divine insight.

There are some features of Kim Sajet’s biography that aren’t far removed from Raven’s. She, too, was born abroad, to Dutch parents living in Nigeria, then was raised in Australia. When she first came to the US, for her husband’s job in Philadelphia, she settled her young family in one of the city’s leafy enclaves. For a brief period, she catered Tupperware parties to keep busy.

But Sajet didn’t take long to establish herself. Back in Australia, she’d been appointed director of a public museum at age 24; now, in Philadelphia, she rocketed through the city’s fine-arts institutions. In 2013, just as Raven began his painting career, Sajet was recruited to lead the Portrait Gallery.

One afternoon this spring, I met Sajet at a restaurant in Clarendon. Wearing broad cat-eye glasses in electric turquoise and matching statement jewelry, she told me about her vision for the museum—a six-year effort, she said, to “go big or go home.” Sajet compared the public perception of the 50-year-old museum to that of a familiar but well-worn sofa. “There was this persistent, and completely wrong, perception that the Gallery was about stuffy old history and dead white men.”

The week she arrived in DC, Sajet distributed an internal list of values. One edict commanded never to tell a lie; another reminded staff that “racism is a social construct.” Soon after, Sajet changed the museum’s language policy so that every artwork was paired with English and Spanish wall text. “I’m from a European family,” Sajet once told a group of employees, “where if you don’t speak at least four languages, you’re not quite up to speed.” Her artistic notions, too, pushed the boundaries: The museum installed a massive American flag imbued with portraits meant to be seen with Google glasses. After that, it was a multicultural “face-scape” tilled into the soil beside the Reflecting Pool.

“There was this completely wrong perception that the gallery was about stuffy old history and dead white men.”

By last year, Sajet had doubled the number of visitors to 2.3 million, a Portrait Gallery record. Crowds had thronged to admire Kehinde Wiley’s and Amy Sherald’s portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama, their unconventional styles an affirmation of Sajet’s heady approach. “Portraiture is now hip,” she says, “but it wasn’t in 2013.”

Sajet had managed to advance her own kind of populism, one that did more to situate multicultural and underprivileged views in the museum. But as Trumpism had brewed in the Republican Party, the Portrait Gallery occasionally became a target. In 2015, for instance, Sajet received a letter from Senator Ted Cruz and 24 Congress members demanding the removal of a bust of Margaret Sanger, an early founder of Planned Parenthood.

The partisan blood feud gradually spilling into Sajet’s world was entirely unnatural to her. Sajet said she couldn’t comment on anything involving Julian Raven. But she seemed to treat the incident like the natural culmination of these events. Looking back on accepting the job, she playfully scoffed at her own ingenuousness.

“Never once, for a second, did I ever think about what it would be like to be part of the Smithsonian,” she says. “It didn’t even occur to me—so stupid.”

After their fiery phone call, Raven took stock. He believed that Sajet had dared him to appeal. So he did. Raven wrote letters to the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, a roster of notables that included billionaires David Rubenstein and Steve Case. “Director Sajet embarked on an undocumented, unofficial, biased and personally opinionated rejection of my painting,” the letter said. (It also used the term “YUGE!” five times.) Two days later, Raven received an e-mail from Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian’s acting provost, who informed him the museum had chosen a different Trump portrait for the inaugural display, a stylized photo taken in 1989. Raven erupted. He wrote another letter trashing the selection. (“Wow! How intellectually stimulating, how enlightening, and O my, how exciting!”)

Time was running out before the inauguration, and Raven decided he would need to escalate: He went to federal court and sued. Raven was now formally taking on the largest cultural institution in Washington.

Forgoing a lawyer, he typed up the lawsuit himself. As with his Portrait Gallery application, the legal brief swings like an alternating current between a rushed history term paper and the agitated diary of a tent-pole revivalist. It cites 26 federal precedents, uses the term “fiduciary” 51 times, and has 108 exclamation marks, in addition to referencing the will of Smithsonian founder James Smithson and the hate-crimes manual for the Bakersfield, California, police department. The essence of his argument was much like the point in his letter: The Smithsonian is not just any institution. “If you were just a private gallery, you could be so arbitrary,” Raven had written to the Regents. But, he noted, the public museum is a trust: It “belongs to ‘We The People,’ and ultimately you work for us.” By declining the portrait, the museum wasn’t simply biased, Raven argued, but guilty of fiduciary neglect.

Shrewdly, Raven also homed in on something unique about the Portrait Gallery. Unlike most public art museums, its artistic purview isn’t merely aesthetic refinement but historical relevance. Raven dug up notes from the museum’s founding commission and cleverly quoted from its own website. “Even today,” it said, “in every instance, the historical significance of the subject is judged before the artistic merit of the portrait, or the prominence of the artist.” The Smithsonian hadn’t merely violated the Constitution, Raven alleged, but its own standards of acceptance. As for damages, he had a figure at the ready: $10 million.

By the time of the inauguration, Raven’s home had become a sprawling mesa of three-ring binders and legal memos. He was internet-surfing his way through the US legal system, writing more bitter letters along the way. He was also trawling for evidence.

The day after the inauguration was the Women’s March. Raven discovered that the Portrait Gallery director’s Twitter page had published an image from the mass protest. There stood Sajet, in a purple-knit pussy hat, smiling beside two friends. One was a Democratic political consultant. The tweet read, “Loved #womensmarchonwashington w. #girlfriends.” Surely, Raven thought, there must be a law, some procedural tripwire he could yank to advance his lawsuit.

Glory be to Google, Raven discovered the Hatch Act. The 1939 law bars federal employees from certain kinds of electioneering. He located the US Office of Special Counsel, the independent agency that administers the law, and wrote another lengthy j’accuse. For emphasis, he followed up with Sajet’s pussy-hat photo and images of Gloria Steinem and Madonna—who, Raven pointed out, had announced onstage at the march that she was thinking about blowing up the White House. “Please investigate this matter and remove from the publically [sic] funded Smithsonian this proudly and politically anti-Trump official,” he wrote.

The ruse appeared to work. Before long, the special counsel’s office opened File No. HA-18-1678 to review Sajet’s actions.

Raven found a source of bottomless publicity with his Hatch Act discovery. On his website and YouTube channel, he mashed up a sinister attack ad that played the Madonna clip and included a badly Photoshopped image of the White House exploding (“KABOOM!”). The Portrait Gallery, however, was in less danger than Raven presumed. Less than five weeks after Raven had filed his complaint, the special counsel’s office told him it had cleared Sajet of wrongdoing. The Women’s March was a 501c(4)—a social-welfare organization—and marching in it wasn’t a violation of the law.

He located the US Office of Special Counsel. “Please investigate this matter.”

That might have been the end of it for Raven. But shortly afterward, he noticed something else: The tweets from the Portrait Gallery director’s account were moved over to Sajet’s personal account, as if they’d been published there all along. Then there was the Smithsonian’s website. Much of Raven’s legal argument hung almost entirely on two sentences from the site that described a “rigorous process” of selection he felt he had been denied. After he filed suit, though, the Smithsonian deleted the phrases. Now museum selections occurred “on a case by case basis,” the site said. “They just change it!” he complained. “They cut my legs off.” (According to a Portrait Gallery spokesperson, the website changes occurred due to a larger overhaul.) To Raven, the two acts confirmed all his instincts of a double-dealing, conspiratorial institution that had wriggled its way from accountability. He appealed to the Smithsonian’s inspector general, wrote to then attorney general Jeff Sessions, and added the complaints to his legal briefs. The response was the same: “They ignored me.”

It hardly mattered. By this juncture, Raven had long ceased painting. He was too busy capitalizing on his political semi-fame. He printed an enormous vinyl banner of the painting and hung it from a building in Elmira. He and his painting were invited to CPAC, the annual gathering of America’s right wing. The artwork appeared on Fox News. Back home, he gave the opening address at the Chemung County Republicans dinner. He began appearing regularly on a local talk-radio show. “He’s got a fan base now,” host Frank Acomb explained. “It’s someone saying, ‘I’m going to take up the same fight as President Trump. I’m not going to be bullied around by Washington.’ ”

By the time we began speaking this spring, Raven was already planning his most ambitious counter-strike yet. He’d found an art gallery in DC that was mounting an exhibit of Trump art and wanted to display his portrait—right across the street from the museum. The gallery’s brochure was already marketing it heavily, urging people to visit the painting “the Portrait Gallery rejected because it was too ‘political.’ ”

Raven was ecstatic. “What a culmination to the journey,” he told me. “It’s going to be epic!”

A month or so later, Raven emerged from a 16-foot Penske truck outside the Center for Contemporary Political Art in DC’s Chinatown. He was greeted by Charles Krause, the gallery’s founder.

Krause—a liberal—had come to art by way of journalism, during 20-some years traveling as a correspondent for the Washington Post and other outlets. His work introduced him to an abundance of authoritarian agitprop. It was the same sensibility he says he detected in Raven’s painting: “It does remind me of the Stalinist, socialist-realism paintings done in that era.” Even so, Krause found the Portrait Gallery’s response far more telling. “When I hear ‘too political,’ ” he says, referring to Sajet’s criticism, “that automatically makes it interesting.”

A few hours later, Raven did a private unveiling for us. With a few theatrical swoops of the hand—the 16-foot painting took up an entire gallery wall—Raven pulled off the tarp that covered it. For a minute, everyone stood in silence.

Trump’s gaze loomed over us. At elephantine proportions, it looked more like some terra-cotta deity than a human face. His skin was a creamy umber, his cheeks raked in a gentle glow—if something that loomed well above Charles Barkley could rightly be called a cheek. At scale, other features became more visible: The eagle’s residence in outer space was now more conspicuous against the twinkling cosmos. Planet Earth, meanwhile, was devoid of landmass besides North America. It was an object so dizzyingly estranged from normal experience that it wasn’t entirely clear if the thing we were craning upward to glimpse even was a painting—and not, say, an acid trip that kicked in with the TV flipped to Lou Dobbs.

By now, we’d been joined by Raven’s 19-year-old daughter, Johanna, who attends a Christian college. She explained that the painting was filled with symbolism: “The more you look at it, the more you’ll see.” She was right. Up close, the US flag was tattered. “Symbolizing, like, just how far this nation has fallen from the beginning of the country,” she said. Johanna pointed to a stripe on the flag, where the words “We The People” were faintly drawn. The ‘W’ had been drawn like a latchkey. “The key unlocks the wall—right there,” she continued, moving her finger up the canvas. Suddenly, a thin, dark wall was visible, snaking its way down the US-Mexico border. Somewhere around Laredo, Raven had drawn a tiny, garrison-like door.

There was more of this. A Star of David under the eagle’s left wing. A second, silver star. (“For police officers,” according to Johanna.) The religious symbolism ran thick. A Statue of Liberty walked on water. It faced a rising sun, the white sun of the East. Three white dots shone in Trump’s pupils, for the divine triune. After a while, even Johanna was depleted. “The moon—I honestly can’t remember what that one means,” she stammered. “Ask my dad.” (It was the waxing crescent, a reference to new beginnings.)

Raven stormed over. There was one more thing. “The floating hair!” he said. “The hair! The hair is not his hair.”

Floating hair?

“It’s a meteor,” he said, a bit barbed. He flipped his notepad open to better explain the physics: “Hair cannot grow straight up in the air off the top of a head!” His portrait’s hair, he murmured, drawing his pen slowly across the pad, “is a comet shape.”

From the start, something didn’t add up with Raven. On paper, he appeared to have all the immoderation of the Trumpian stock character. What was peculiar was how quickly, and thoroughly, this mold disintegrated when in Raven’s presence. The staff at Krause’s gallery was equally flummoxed. By one turn, Raven could be discussing the finer points of divine intervention; the next, he was quoting Cervantes or Hogarth. “That’s the thing I still don’t understand,” Krause confessed, out of Raven’s earshot. “He’s clearly smart. But . . . .” He trailed off. But predestination. But the space eagle.

Raven’s actual politics were no less inscrutable: He called himself a “rational mystic.” Besides an affection for oxymoron, I was curious to know what a rational mystic believed in. Raven described the Founding Fathers as deeply religious and explained his theory that the Gettysburg Address contained religious code. As for the President, “Trump has a lot of issues, there’s no denying that,” Raven said. “It’s not excusing his sins. I pray for the man, that God converts him.” Raven recited the biblical story of Cyrus, a pompous nonbeliever chosen to carry out the Lord’s will. He also had some opinions on prayer in school and radical Islam, briefly describing the Muslim plan to take back Spain. Ultimately, it was simple: He deferred to the reverend Franklin Graham, son of Billy Graham, who has called Trump “the most Christian-friendly President” in his lifetime. What more needed to be said?

Occasionally, people who heard these notions lumped Raven in with the alt-right. That characterization was false, Raven said, but he was refreshingly sympathetic to the charge. Once, on his Facebook page, he’d denounced Alex Jones, an alt-right hero, as “#FAKENEWS”—and been pilloried for it. “ ‘He’s a patriot!’ ” Raven sneered, quoting the conspiracy theorist’s defenders. “No, he’s a pig.”

In fact, Raven felt that his battle with the Portrait Gallery had been misconstrued as unduly partisan, obscuring the work’s true meaning: unity. “Bipartisanship is painted into the painting!” he said. The stars were red and blue—“politically inclusive”—along with corresponding red and blue states. I must have looked skeptical, so he leaned in.

“When Obama won, I cried. I wept. Because I said, ‘How far our country has come!’ ” His friends on Facebook were not amused. “They were disgusting in their insults.” He threw his hands up beseechingly. “You can disagree with people!” he cried. “I can disagree with the man. I can sit down and have a beer with him. And that’s America! God, if we don’t get that right, we’re screwed.”

That was the real reason his painting was under attack: too hopeful. “It was positive, and it didn’t ride with the narrative that Trump supporters are hateful, racist, ignorant bigots—you know, this type of thing they push.”

On the night of the exhibit’s debut at Krause’s gallery, some 50 people filed in—rolled-corduroy art students, blue-jeaned drop-ins, a few from the after-work crowd. Virtually every piece on display was derogatory of Trump, including several that depicted him as a humanoid-swine hybrid.

Someone said, “There he is,” and Raven appeared dressed in a white tuxedo.

But it was Raven’s painting that drew a conga line of slack-jawed gawkers. The portrait was a crypto-fascist ode to Vladimir Putin, they muttered, or an unintentional meta-kitsch of Jeff Koons, or a proficient work of serious art. A man in a tweed jacket and bow tie, Angel Gil-Ordóñez—director of Georgetown University’s orchestra, who said he grew up in Francoist Spain—offered a clever postmodern gloss on the situation. “It is fantastic! It’s propaganda!” he cried. “But it’s propaganda we need right now. You see?”

Eventually, someone said, “There he is,” and Raven appeared. He was dressed head to toe in a white tuxedo, down to the vest and tie, cummerbund, and polished round-toe shoes, an ensemble he’d rented from Men’s Wearhouse.

When it came time for the artists’ introductions, Raven offered up more remarks about civility. Johanna filmed from the back of the room. “Let’s argue, let’s debate,” he said to polite applause. “Let’s go have a beer and let’s relax. But if we don’t, we keep driving our country into this dark, dark place.” Later, I found him near the hors d’oeuvres, his face somewhat drawn. He’d been hoping for a bigger turnout.

Raven had contacted every Washington media outlet he could think of—even Tom Reed, a New York congressman who had endorsed his Portrait Gallery application. Raven suspected the Smithsonian’s prestige had kept people away. He suddenly seemed eager to leave. “I’m in character right now,” he said, nodding at his white trousers. “I’ll play my part. Then I’ll go home, take this off, and go back to my studio covered in paint.”

Around the exhibit, there was some talk of Sajet and what now seemed like the defining riddle of a two-and-a-half-year saga: Why had she called Raven?

Most agreed it was unusual to receive a 12-minute telephone rejection from the director of a national fine-arts institution—a privilege not even necessarily afforded to artists of renown. (Sajet declined to comment on the case, which is still pending.)

Raven, for his part, insists he would have backed down if he’d received a polite form letter. He wasn’t afraid to admit that his obsession was personal. “She just mocked me. . . . She knew what she was doing,” he said. “There was no accident. I believe it’s because of the animus and the bias. There’s just no doubt.”

I saw the cheery civic naif curdle into someone temperamentally closer to Steve Bannon.

Actually, when the court finally ruled on the case, the presiding federal judge agreed—to a point. Even as he decided against Raven, Judge Trevor McFadden singled out Sajet’s treatment of the artist. The phone call was “odious,” wrote McFadden, a Trump appointee, amounting to “a professional insult . . . partisan and undeserved, against Mr. Raven and his work.”

The ruling had come down last fall, but Raven had taken no comfort from any of it and had all the while been busy appealing alongside his PR stunts. None of it was going terribly well. He’d set up a press conference outside the Portrait Gallery to coincide with the exhibit across the street. Only one person attended: me. As he mugged for tourists with iPhones on the museum’s steps, Kim Sajet walked right behind him. Raven was too preoccupied to notice.

If anything, this latest Washington visit seemed to chasten him. In the two months I’d known him, I’d seen the cheery civic naif appear to curdle into someone temperamentally closer to Steve Bannon. More and more, he talked about the uselessness of rule-enforcers and the corruption of referees, his tone drenched with contempt. “The Smithsonian,” he said, “is diseased.”

Raven was enacting all the elements of grievance politics that form the soul of Trumpism—thrashing against institutions seemingly unaccountable to their own rules, demanding reprisal through a tendentious righting of wrongs. But the problem, of course, was thornier than that. The Portrait Gallery saw a familiar picture of a garish outsider from New York, laying siege to a centuries-old institution he knew nothing about. Raven saw a case study of rootless globalists falling into possession of a national treasure, wielding the levers of power to lock out true patriots. Neither was entirely wrong. One irony of Trumpism is that both institution and citizen come to feel its lash, as both believe they’re the object of bullying. It’s not clear what museums can do to stanch this tide. But just as there are analogies in the Trump era, there may be lessons, too, and one of the most hard-bitten examples is that calling people “deplorable” and hanging up the proverbial phone tends, in the balance, to make things worse.

What did the Washington art world make of all this? In conversations, few at the Smithsonian or elsewhere were acutely concerned about the Raven case. What lingered, though, was something more disquieting: a sense that, though they had dealt with the first Julian Raven, sooner or later they would meet the next dozen.

Not long after the art show, I found a video that Raven had mashed together from a BBC television series and had recently uploaded*. In it, a retinue of 19th-century French curators, donned in top hats and morning coats, snootly survey artworks for an exhibition at the Louvre. He’d rigged the background audio with crude sound effects—toilets flushing, crowds jeering—and injected images of Sajet and Kurin, the Smithsonian provost. Raven had messily plastered a pink pussy hat on Sajet’s head, alongside a small Australian flag, then gyrated her body around the screen like a rag doll. For the first time, I thought he’d entered scary territory.

At the end of June, he called with bad news: He’d lost his first appeal. But he had 45 days to write a new brief. He spoke loudly over the crunch and hiss of power tools—hard at work on his next series, he said. It was called “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,” a depiction of the White House in spring. “When I’ve got God on my side,” he told me, “he’s leading me into this battle—I know I’m going to prevail.” Then there was the hoarse whine of a buzz saw, and it drowned out everything else.

This article appears in the August 2019 issue of Washingtonian.

*This story has been corrected to reflect that the video was not uploaded after the art show.