It’s safe to say Washington is one of the better-documented cities on Earth. Last year alone, the roster of books set in and around here included headline-snagging national bestsellers (Michael Wolff’s devastating account of the Trump-era capital, which sold 1.7 million copies in three weeks) as well as slightly less buzzy works (George Mason professor Dae Young Kim’s study of how information technology affects the region’s Korean immigrants, which almost certainly did not sell 1.7 million copies).

But what would you read if you really wanted to understand the place? It’s a tricky question, even if you can get people to agree on what constitutes a “Washington” book anyway. A complete library would include human stories set in everyday neighborhoods and heroic tales of globetrotting statesmen—but also poison-pen political memoirs and reportage on now-forgotten Beltway scandals.

Rather than answer the question ourselves, we invited a long list of locals to send nominees. We made the mission simple: We weren’t looking for the best books, necessarily. We were seeking the ones they’d recommend to someone who wanted to know what makes our region tick.

Suggestions ranged from 1816’s A Chorographical and Statistical Description of the District of Columbia, the Seat of the General Government of the United States by David Bailie Warden (“A key book to understanding what the District was like in its earliest days and why President Washington chose the area,” said Matthew Gilmore, a D.C. Policy Center fellow) to For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Politics by Donna Brazile, Yolanda Caraway, Leah Daughtry, and Minyon Moore (“We get to see how Washington works from the perspectives of four black women who have risen through different ranks over three decades,” said Washington Post writer Jonathan Capehart). And though we had to exclude a few—New York Times columnist and DC native Maureen Dowd’s choices included Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth—we tried to keep our definition as inclusive as possible as we winnowed the field. Here’s a start.

Political Fiction

Political Fiction

Advise and Consent by Allen Drury

“Advise and Consent is one of those classics that you’ve heard of a million times. But I didn’t read it until last year, when I saw an interview John McCain gave before his death to the Times Book Review. He said something like, ‘This is not only a great Washington novel but the most accurate account of Washington.’ I found that to be true. It’s almost a fictionalized version of Robert Caro’s Master of the Senate, about LBJ. Advise and Consent shows, for example, that the Senate is made up not of abstract ideologies but real people. It’s still the best portrait of the Senate as a living, breathing institution of individuals driven by their own histories and concerns, and how that dynamic works.

“It’s certainly a period piece—parts are highly specific to Cold War–vintage, pre-women’s-liberation, pre-gay-liberation DC: the majority leader who lives in the Sheraton Park Hotel in Woodley Park, the big parties given by his girlfriend—sort of based on the famous hostess Perle Mesta—where lots of Washington business gets transacted. Characters are concerned about editorials in print newspapers as driving events.

“But much remains relevant to the Trump era. At its heart is this oddly progressive take on a senator who had a gay affair in World War II, and the threatened exposure of the affair becomes the centerpiece of the tragedy surrounding a Secretary of State confirmation fight. That part resonates across the decades, and it’s the reason why if you Google ‘Brett Kavanaugh and Advise and Consent Allen Drury,’ you’ll get a lot of hits.”

—Susan Glasser, as told to Luke Mullins

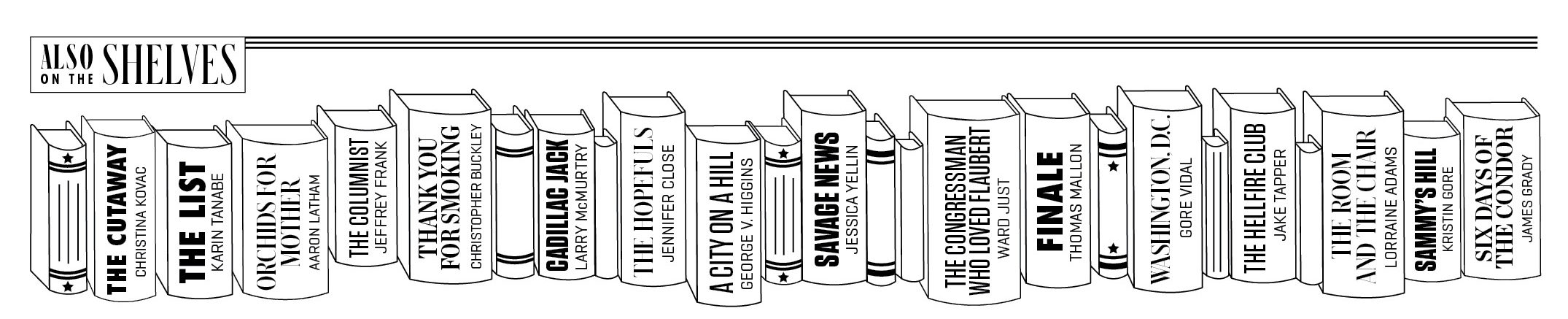

Political Fiction: Five More

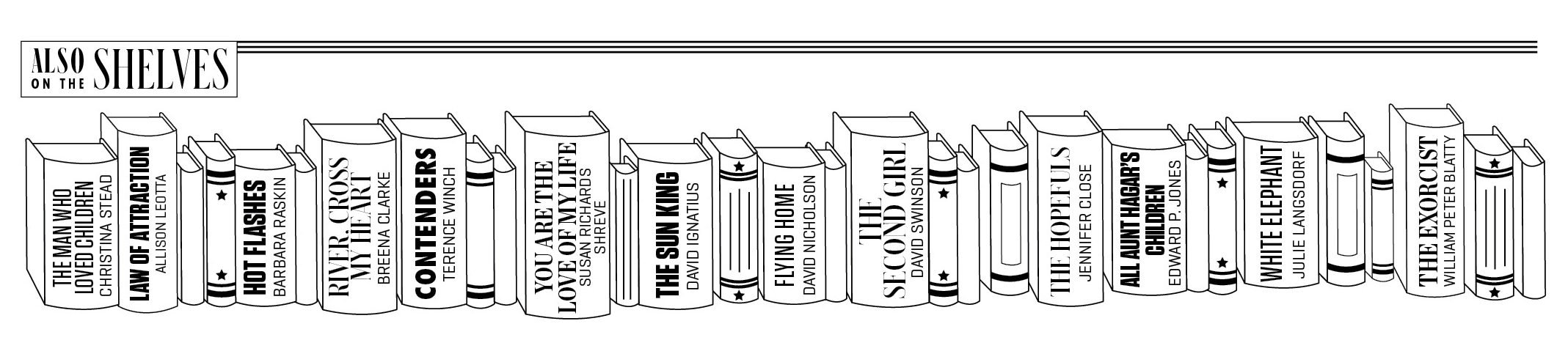

Conflict of Interest by Les Whitten. The ’70s language will make you cringe, but this tale of a journalist taking on a crooked House speaker nails the mood of the hunt and the dealings among reporter, prey, and sources.

Democracy by Henry Adams. “A must-read filled with politicians and spouses who engage in partisan politics, backstabbing, and double talk.” —Maureen Corrigan, NPR book critic, Georgetown professor

Echo House by Ward Just. “This beautiful novel tells of three generations of power in a way that actually makes this youngish capital seem venerable.” —Burt Solomon, author of The Washington Century

1876 by Gore Vidal. It follows Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler from New York to a Washington wrenched by that year’s too-close-to-call election aftermath. But the narrator is really DC native Vidal at his catty best.

Watergate by Thomas Mallon. “His political novels are full of delicious cameos and gorgeously written. This is the best, wedded to fact yet novelizing its way to deeper truths.” —Franklin Foer, Atlantic writer

Essential Genre: Novels by Pols

The Fiction Caucus

What’s better than fiction about politics? Fiction by politicians. Actually, that’s not usually true—but it isn’t for lack of trying by generations of electeds. Some examples, for better or worse:

Ignatius Donnelly, Caesar’s Column. A 19th-century congressman both noble (pro-suffrage) and oddball (a Lost City of Atlantis believer), Donnelly set his novel in a future with no Reagan but lots of class tension. (He also may have foreseen the Apple Watch.)

Ignatius Donnelly, Caesar’s Column. A 19th-century congressman both noble (pro-suffrage) and oddball (a Lost City of Atlantis believer), Donnelly set his novel in a future with no Reagan but lots of class tension. (He also may have foreseen the Apple Watch.)

Gary Hart, The Strategies of Zeus. Infidelity killed his presidential hopes, but Hart got to show off Big Thoughts as a prolific novelist. Here, a US negotiator and his comely Russian counterpart try to save an arms deal from troglodytes on both sides.

Gary Hart, The Strategies of Zeus. Infidelity killed his presidential hopes, but Hart got to show off Big Thoughts as a prolific novelist. Here, a US negotiator and his comely Russian counterpart try to save an arms deal from troglodytes on both sides.

Newt Gingrich, Treason. A Marine heroine must foil a terrorist mastermind while contending with a ditzy female President and dull-witted pols. In Gingrich fashion, there are good guys, bad guys, and nothing in between.

Newt Gingrich, Treason. A Marine heroine must foil a terrorist mastermind while contending with a ditzy female President and dull-witted pols. In Gingrich fashion, there are good guys, bad guys, and nothing in between.

Barbara Mikulski, Capitol Offense. The legendary Maryland pol’s heroine becomes a senator after the incumbent keels over at a polka contest. More untimely deaths follow!

Barbara Mikulski, Capitol Offense. The legendary Maryland pol’s heroine becomes a senator after the incumbent keels over at a polka contest. More untimely deaths follow!

Barbara Boxer, A Time to Run. Elected to the Senate after the Clarence Thomas hearings, Boxer creates a revenge fantasy with her doppelgänger defeating a conservative SCOTUS nominee.

Barbara Boxer, A Time to Run. Elected to the Senate after the Clarence Thomas hearings, Boxer creates a revenge fantasy with her doppelgänger defeating a conservative SCOTUS nominee.

—Matthew Cooper

Other Fiction

Other Fiction

Lost in the City by Edward P. Jones

I hadn’t read the book in 20 years. Yet when I revisited its first lines, that sense of being baptized into something new—something that would set its own rules and become necessary and important—the feeling came back in a flash. The stories in this debut collection from 1992, which established the author’s meditative, deeply humanistic style, are masterpieces. Jones is the griot of black DC, the archaeologist of the tangle of tragedy and bittersweetness that is the grit and the soil of our lives.

Here, the city is a landscape of boundaries and borders, migration and flight, loss and renewal. It becomes such a breathing organism that we feel the tremor as its heart breaks, just as we see it occasionally smile at a wall torn down, a race finally won. Jones writes of one character, “In both his lives, he had never come down to the world below Constitution Avenue.” Seaton Elementary is where a first-grader learns of her mother’s inability to read. Characters take the G2 bus “all the way down P Street crossing 16th Street into the land of white people.”

Since these stories were written, the streets and communities in them, rendered with surgical love and care, have been transformed. Glass office buildings, modern condos, grocery stores as alluring as cathedrals have replaced the rooming houses and walled-off lives of Jones’s people. Yet DC remains much the same: a city of quadrants that rarely intersect, races that seldom mix. These are characters whose small lives are startling, majestic, heroic. Devoid of sentiment yet shot through with an understanding of love and despair. A grandfather warns a grandson, “Don’t get lost in the city,” but this book reminds us we are always in some way lost. And what we call living is just finding our way home.

—Marita Golden

Other Fiction: Five More

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears by Dinaw Mengestu. “Twelve years post-publication, the insights about democracy and diaspora are only more prescient.” —Journalist Katherine Boo

Cane by Jean Toomer. “It mixes short prose with poems in an innovative style to render both rural Georgia and DC’s Seventh Street district, then a working-class black neighborhood.” —literary historian Kim Roberts

Heartburn by Nora Ephron. “A gut punch. I read it at age 13 in Eastern Europe and thought these people’s friends, parties, way of talking were the kind I wanted.” —Svetlana Legetic, cofounder of Brightest Young Things

The Stager by Susan Coll. Of course a great modern DC novel would involve real estate. A successful PR superwoman lands a gig abroad and must unload her gargantuan Bethesda home. A deliciously wicked satire.

When Washington Was in Vogue by Edward Christopher Williams. “Fascinating as an anthropology of the black elite living around Howard in the 1920s.” —Natalie Hopkinson, author and journalist

Essential Name: George Pelecanos

The Pelecanos Brief

Esquire called George Pelecanos “the poet laureate of the DC crime world.” In fact, he may be the most popular working Washington novelist, the rare writer who can conjure convincing characters from across our racial chasm. Less remarked upon: Set in a variety of periods, Pelecanos’s books represent something of a cultural history of hometown DC. A sampling:

1950s

1950s

The Big Blowdown. Spans the decade and a half after WWII as Washington becomes America’s first black-majority big city.

1960s

1960s

Hard Revolution. The tale of a black rookie cop picks up in 1968 as riots engulf the city.

1970s

1970s

King Suckerman. Takes place in 1976 in a world of soul music, blaxploitation, and the apogee of Chocolate City.

1980s

1980s

The Sweet Forever. Set in 1986 against the backdrop of the cocaine-related death of basketball star Len Bias and the arrival of crack.

2010s

2010s

The Man Who Came Uptown. Getting out of jail, the protagonist emerges into a city transformed.

How Washington Works

How Washington Works

This Town by Mark Leibovich

In theory, Mark Leibovich’s report from glittering post-recession Washington could have been a you’ll-never-eat-lunch-in-this-town-again moment for the writer. After all, his book—a combination of reporting, anthropology, and comic slicing and dicing—skewered people by name, hitting everything from how they threw parties to how they made money to how they mourned. But what would be the fun in that? If there’s anything Leibovich’s insidery depictions of status-seeking and celebrification taught, it’s that a guy whose book became a meme would never go hungry in #thistown.

Six years later, though, the evisceration feels more like That Town, a dispatch from a zany foreign country. In other words, it has joined an illustrious list of books that absolutely nailed some aspect of how Washington works, only to find themselves overtaken by events. David Halberstam’s The Best and the Brightest (1972) delivered a searing portrait of Ivy League types whose prescriptions for Southeast Asia went unquestioned. Thanks in part to Vietnam, such CVs don’t go quite so unquestioned anymore. Hedrick Smith’s The Power Game (1988) shone a light on behind-the-scenes media advisers and their hidden arts. Thirty years on, those arts are no longer so hidden.

And Leibovich’s chummy old swamp full of oblivious partygoers? Uh . . . that’s so six years ago. Of course, none of that means there’s no utility to yesteryear’s how-it-works bestsellers. Journalism becomes history pretty fast—and this is awfully entertaining history. So if, say, you’re wondering how Hillary Clinton’s circle never saw it coming, you’d find worse places to turn.

—Michael Schaffer

How Washington Works: Five More

All the President’s Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. “This helped change journalism—you, too, could be as rich and famous as Woodward and Bernstein—and was a great book.” —Jack Limpert, former Washingtonian editor

Parliament of Whores by P.J. O’Rourke. “I reread this once a year. It’s still sharp as a newly stropped straight razor. And a lot funnier.” —Christopher Buckley, whose novels include Thank You for Smoking

Strange Justice by Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson. “The authors reconstruct the lurid farce of Clarence Thomas’s confirmation, with details such as the scene where attorney Fred Cooke Jr. ‘thought it pretty amusing to run into the chair-man of the EEOC . . . standing with a triple X videotape entitled The Adventures of Bad Mama Jama.’ ” —Sasha Issenberg, journalist

Washington by Meg Greenfield. A sly dissection of the capital—home to “the fatal, ever-present . . . temptation: disappearance into the abstract, bloodless, phony, self-inflating world of endless competitive image projection”—and an insightful account of one journalist’s journey through that land.

The Woman at the Washington Zoo by Marjorie Williams. Part profiles of such figures as Bill Clinton and Al Gore (“Scenes From a Marriage”), part essays culminating in the award-winning “Hit by Lightning: A Cancer Memoir,” it’s a lesson in writing about Washington life, public and intimately private.

Literary Agents

Essential Genre: Spies Who Write

Unlike policy tomes, thrillers are supposed to be escapist. But there’s one realm in which wonky, how-Washington-works detail is key: spy fiction, a verisimilitude-obsessed local genre that can sometimes be as much about bureaucracy as geopolitics. Not surprisingly, it has seen veterans of Washington’s foreign-policy scene—espionage officials, political journalists—thrive. A sampling, in order of the authors’ insider cred:

Robert Baer was a CIA field operative working in some of the world’s nastiest places. He poured all that into Blow the House Down (2006), a haunting, too-ignored alternative history of 9/11. The storyline sprawls across the globe, but ultimately it’s all about Washington.

Jason Matthews’s turbocharged 2013 debut novel, Red Sparrow— the first of a trilogy—is informed by his 33 years as a CIA agent, much of that time in “denied areas.” Oddly, even sweetly, he eases off the accelerator at the end of each chapter with recipes, for everything from blinis to kebabs.

Charles McCarry, another ex-spy—who died this year—lived a full second career as a novelist. He is to the CIA what John le Carré has been to England’s MI6: its master tragedian. McCarry’s crown jewel, Tears of Autumn (1974), is more than a thriller. It’s a great American novel.

Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II had solid Washington chops—Knebel as a political columnist, Bailey as a newspaper bureau chief—and they put that experience to excellent use in 1962’s Seven Days in May, about a clash between the White House and the Pentagon. Could a coup really happen here? Why not?

Robert Littell’s The Company (2002) is epic in length (almost 900 pages), ambition (a bona fide thriller and a rollicking history of the CIA), and achievement: Despite its heft, The Company never loses steam. Littell clearly kept his eyes wide open during his 1960s stint as a Newsweek foreign correspondent.

—Howard Means

Modern History

The Books on Brett

Depending on your view, Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings were either a triumph, a travesty, or a tragedy—or some combination thereof. But one thing is undeniable: They were very good for Washington book sales.

Within weeks, journalists for three major news organizations had announced plans for books about the spectacle. And why not? It was the latest example of a classic archetype: the subject that explains everything. In this case, it had gender, ideology, fairness, power, lobbying, entitlement, media dynamics, political strategy, the future of the nation—and a decades-old past that, in Washington, literally hits close to home. Add it all up and you have a master class in how the capital works, for teenage prep-schoolers and power-class denizens alike.

The first books have landed already and, naturally, look like they’ll be reaching different audiences: Conservative writers Mollie Hemingway and Carrie Severino’s Justice on Trial hit bestseller lists this summer, while New York Times reporters Kate Kelly and Robin Pogrebin’s The Education of Brett Kavanaugh made news in September for reporting another alleged incident of college sexual misbehavior.

Didn’t read them? That’s okay. By the time the next Supreme Court confirmation controversy happens, Kavanaughiana might have its own Library of Congress classification number.

Memoir and Biography

Memoir and Biography

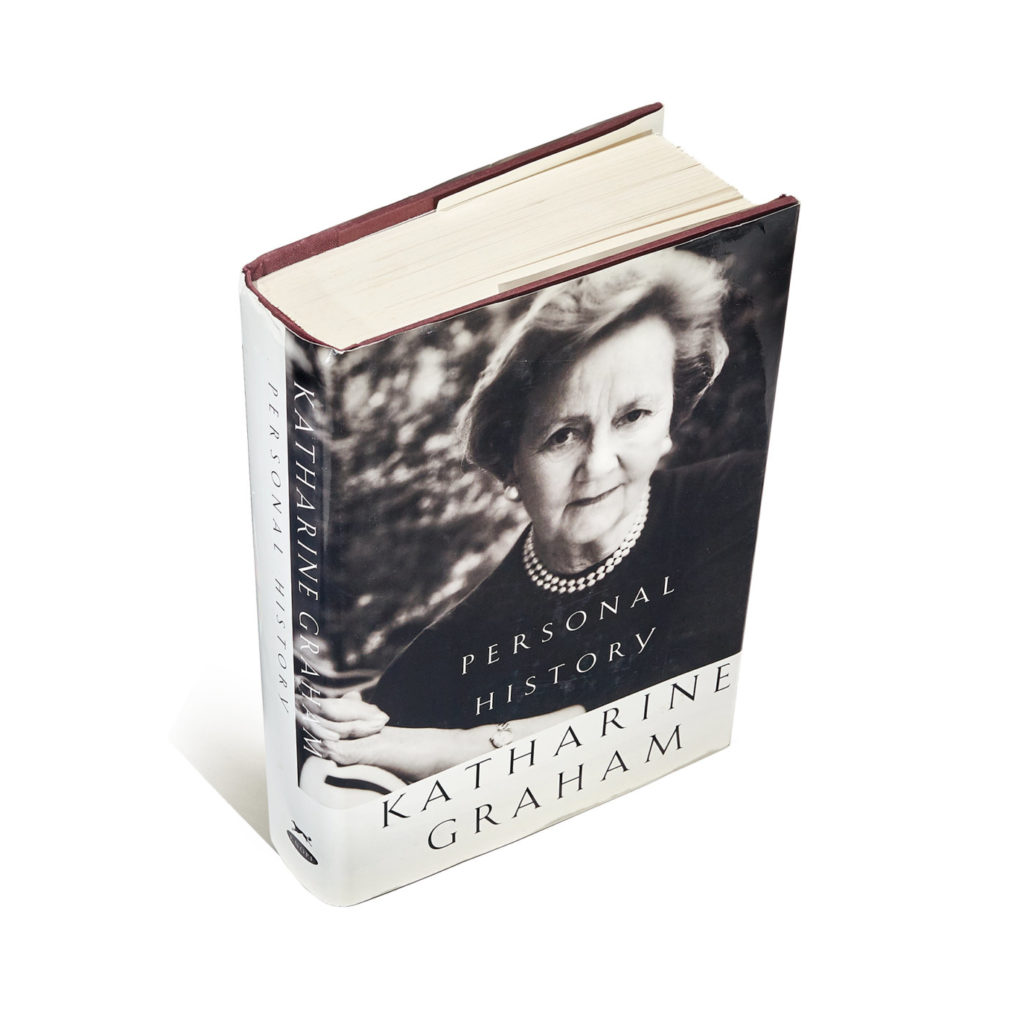

Personal History by Katharine Graham

Don’t think you can skip reading Personal History because you’ve seen the movie The Post or read All the President’s Men. Graham is perhaps best known for presiding over her newsroom during Watergate as well as her courageous decision to publish the Pentagon Papers, but the events that put her at the helm of the Washington Post are just as dramatic. In addition to delivering on its promised historical sweep, this Pulitzer-winning memoir will leave you with new admiration for a vulnerable woman who had a remarkable gift for grace under pressure.

More than 20 years after first reading it, I vividly recall her complicated family life and her loneliness amid great privilege. The patrician publisher also provides a granular portrait of a city and a country in the midst of sweeping change. Graham came of age in an era when, despite her accomplishments, it was accepted that leadership of her family’s newspaper would be handed to her husband. But when the brilliant and deeply troubled Philip Graham committed suicide in 1963, she stepped into the male-dominated newsroom and steered the Post through tumultuous political times.

Graham writes of a city of long-gone department stores like Woodward & Lothrop, of neighborhoods restricted against blacks and Jews. She crosses paths with many of the 20th century’s most storied characters, including Einstein, JFK, and Capote.

Personal History is a love letter to a newspaper and a reminder of the intention that a paper must be a public trust.

—Susan Coll

Memoir and Biography: Five More

All Too Human by George Stephanopoulos. “A hall-of-fame White House memoir. A perfect mix of deeply personal, candid, and for history’s sake.” —Mark Leibovich, New York Times Magazine correspondent

Behind the Scenes by Elizabeth Keckley. “After buying her freedom, she became Mrs. Lincoln’s dressmaker. An upstairs/downstairs look at the White House.” —David Nicholson, author of Flying Home

A Political Education by Harry McPherson. The 1960s White House lawyer’s fall-from-innocence memoir recounts backstabbing and duplicity—and moments of great accomplishment.

The Wise Men by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas. A group bio of foreign-policy advisers to Presidents from FDR to LBJ. “A wonderful illumination of the use of power.” —Sally Quinn, journalist

The Years of Lyndon Johnson by Robert Caro. Known as a biographer, Caro is actually a student of power. And after four volumes, he has reached only the beginning of Johnson’s presidency.

Essential Genre: Poison Pens

Best Served Cold

Ousted aides and disillusioned insiders may not write the kind of doorstop books preferred by ex-Presidents, but there’s another classic DC genre—the poison-pen tell-all. Some examples:

Donald T. Regan, For the Record. Ronald Reagan’s ousted chief of staff described, among other things, a First Lady in thrall to an astrologer. Stylish vitriol from a gruff former Marine.

Donald T. Regan, For the Record. Ronald Reagan’s ousted chief of staff described, among other things, a First Lady in thrall to an astrologer. Stylish vitriol from a gruff former Marine.

Ron Suskind, The Price of Loyalty. Paul O’Neill was booted from W’s cabinet but got revenge by sharing his story with reporter Suskind. Memorable: POTUS was like “a blind man in a room full of deaf people.”

Ron Suskind, The Price of Loyalty. Paul O’Neill was booted from W’s cabinet but got revenge by sharing his story with reporter Suskind. Memorable: POTUS was like “a blind man in a room full of deaf people.”

Richard A. Clarke, Against All Enemies. A classic of the “you should have listened to me” subgenre. Clarke was at the heart of the US response to 9/11 and blasts the White House for ignoring the threat.

Richard A. Clarke, Against All Enemies. A classic of the “you should have listened to me” subgenre. Clarke was at the heart of the US response to 9/11 and blasts the White House for ignoring the threat.

Jill Nelson, Volunteer Slavery. Nelson recounts her Post tenure. “Whatever field we’re in, we have to justify ourselves daily to people who’d rather we weren’t around,” she says of fellow African Americans at white-run institutions.

Jill Nelson, Volunteer Slavery. Nelson recounts her Post tenure. “Whatever field we’re in, we have to justify ourselves daily to people who’d rather we weren’t around,” she says of fellow African Americans at white-run institutions.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Adam by Adam. The Harlem pol calls himself Congress’s “first bad nigger.” Targets include Dems who stripped him of his seat after a scandal. The court restored him, but he never mellowed.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Adam by Adam. The Harlem pol calls himself Congress’s “first bad nigger.” Targets include Dems who stripped him of his seat after a scandal. The court restored him, but he never mellowed.

—Matthew Cooper

Hometown Washington

Hometown Washington

Dream City by Harry S. Jaffe and Tom Sherwood

In 1995, David Carr hired me at Washington City Paper. I was from Utah and didn’t know much about local politics, so he insisted I read Dream City. The book was published in 1994, just before “mayor for life” Marion Barry was elected to a fourth term, despite serving six months in jail after being caught in a drug sting. Carr saw Barry’s comeback as alt-weekly gold, but to tell the stories that would come, his reporters needed to understand how Barry got there. Dream City helped me make sense of the complicated politician whose influence can still be felt.

Media coverage at the time treated Barry as a late-night joke, but Jaffe and Sherwood refused to draw a caricature. They told of a militant civil-rights warrior, called a “bama” and a “cotton-pickin’ n-gger” by the black bourgeoisie, even as he helped make many of them rich with city jobs and lucrative sole-source contracts to provide substandard human services to poor residents. The authors also knew the real beneficiaries of Barry’s corruption were white real-estate developers who got favorable treatment by the city in exchange for campaign contributions that helped keep Barry in office long after he’d run it into the ground.

Barry died almost penniless, but his legacy lives on in the city’s dismal human services and homeless shelters. Notorious places featured in the book— such as the Pitts Motor Hotel, where he funneled millions in taxpayer dollars to a crony to house homeless families in horrible conditions—are now luxury condos. But ultimately, Dream City was bigger than Barry, which is why it remains relevant. It’s the story of a majority–African American city’s long struggle to free itself from white congressional overlords and create a functioning democracy, warts and all.

—Stephanie Mencimer

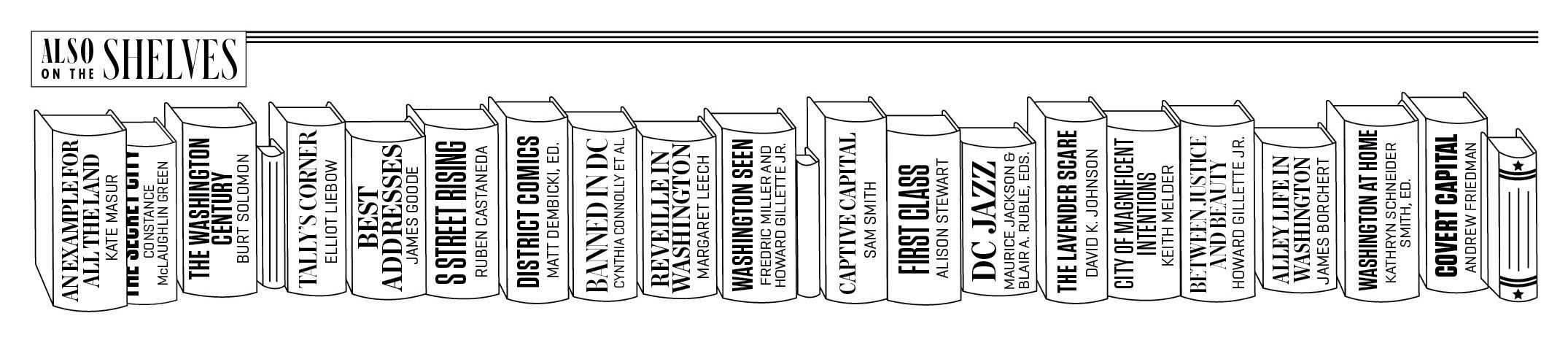

Hometown Washington: Five More

Chocolate City by Chris Asch and Derek Musgrove. A two-century history of DC that puts race relations front and center—whether or not each era’s protagonists wanted to put them there.

Go-Go Live by Natalie Hopkinson. “I got to college in New York in the late’90s, and no one knew what go-go was. Everyone associates DC with politics, so I love this look at its contribution to music.”—Karin Tanabe, novelist

The Great Society Subway by Zachary M. Schrag. “Metro is key to DC’s development, and Schrag details its creation. Great background for its dysfunctions.” —Matthew B. Gilmore, D.C. Policy Center fellow

Washington Goes to War by David Brinkley. “A breezy look at how WWII transformed DC into a bustling city where every inch of real estate went to the war effort.” —Michele Norris, journalist

Worthy of the Nation by Frederick Gutheim and Antoinette J. Lee. “The best introduction to Washington’s growth, in both architecture and planning.” —Zachary Schrag, GMU history professor

Ancient History

The First Great Washington Novel?

Margaret Bayard Smith’s A Winter in Washington, or Memoirs of the Seymour Family (1824) is an ambitious early novel of Washington, set during the Jefferson administration, when the new capital was a village and the President held holiday parties in his new residence.

In real life, Smith was an outsider, a “trailing spouse” who came to the city with her husband, Samuel Harrison Smith, when the President persuaded him to start a Jeffersonian newspaper, the National Intelligencer. The two brought considerable social and political standing with them and quickly joined the capital’s elite. A Winter in Washington, which runs to three volumes and 800 pages, is a novel of manners in that society’s upper echelon, including diplomats and foreign dignitaries.

It’s also designed to grip readers. In a bold move, the author included the President himself as a character and kept excitement high with sensational incidents: forgery, kidnapping, seduction, murder, a duel, a suicide, a shooting, the appearance of a tall stranger. For most of Smith’s narrative, though, the worlds of men and politics are in the background while she works on dramatizing the domestic life of the Seymour family and their friends as they watch over the younger generation’s romances, attend balls and parties, and make occasional forays to Capitol Hill to witness its fledgling institutions at work. Attuned to the emerging values of a new democracy, Smith gives special attention to the social and moral education of the young and the responsibilities of the privileged. She treats the world of men, of government and politics, as a distant sideshow.

Still, she writes with pride about the American system of values where women can speak their minds. Smith provides only brief glimpses of African Americans—alas, as loyal, lovable servants or house slaves. But she describes in detail the life of the poor, particularly Irish and Scottish immigrants who came to the city looking for construction jobs but were never paid and had to get by on fish from the river, menial day work, and the assistance of Catholic charities or public-spirited women like Mrs. Seymour and her daughters.

—Christopher Sten

Illustrations by Jenny Rosenberg

This article appears in the November 2019 issue of Washingtonian.

Political Fiction

Political Fiction Other Fiction

Other Fiction 1950s

1950s 1960s

1960s 1970s

1970s 1980s

1980s 2010s

2010s How Washington Works

How Washington Works Memoir and Biography

Memoir and Biography Hometown Washington

Hometown Washington