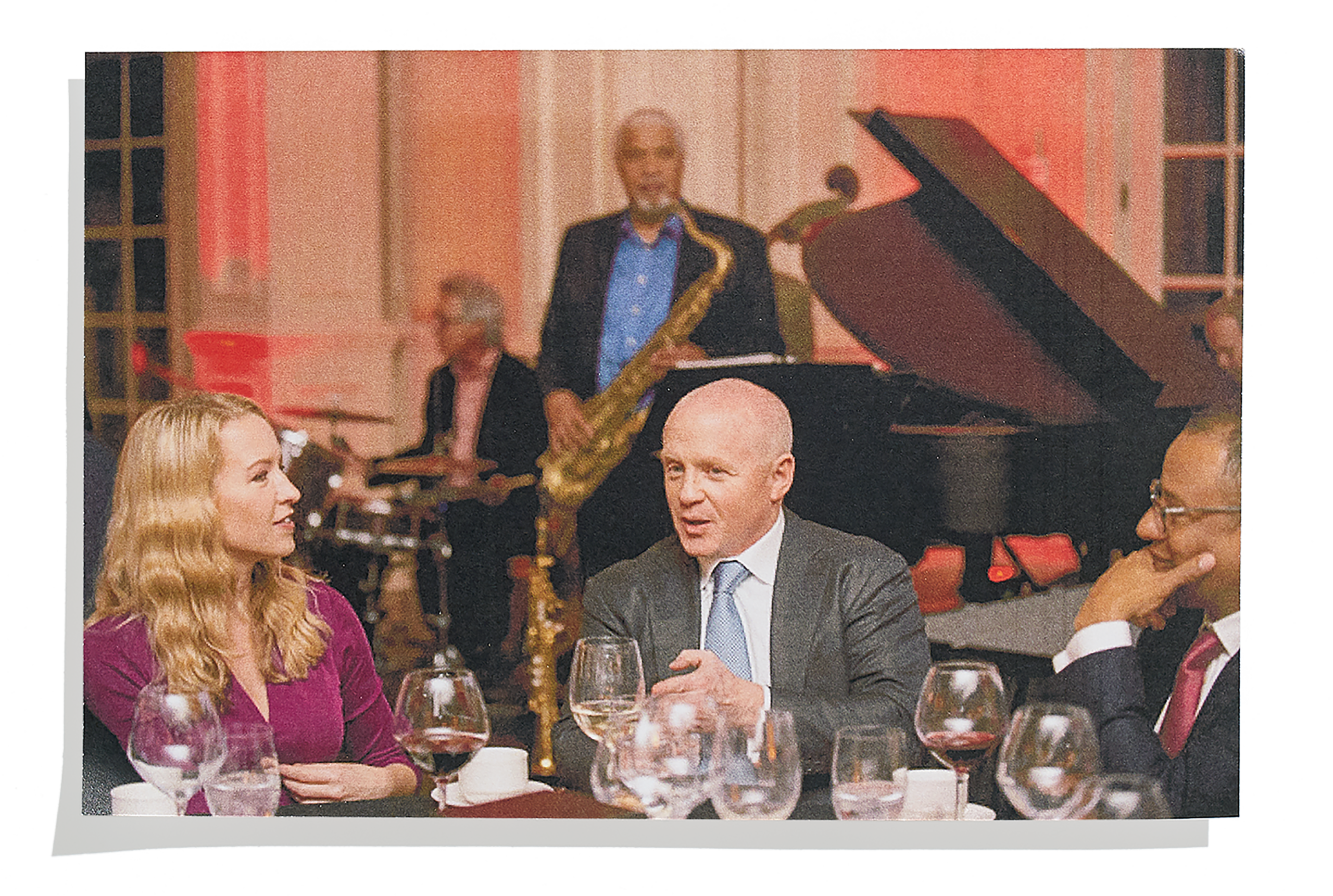

It was the biggest bash on Friday night of the 2018 White House Correspondents’ Dinner weekend, a glam affair at the British ambassador’s residence. One of the UK’s hottest techno stars DJ’d. DC VIPs and out-of-town celebs danced beneath the mansion’s crystal chandeliers and sipped Macallan single-malt in the English gardens. Nancy Pelosi and Sarah Huckabee Sanders posed for pictures. And in the swirl of it all, outfitted in one of his flashy double-breasted suits, hobnobbing with entrepreneur Mark Ein and ousted White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci, was the evening’s top sponsor—Todd Hitt.

In return for bankrolling a large chunk of the tab, the name of Hitt’s private-equity firm, Kiddar Capital, was everywhere: projected in shimmery white light on the building’s facade, emblazoned on the step-and-repeat, stamped on the cocktail napkins. Hitt’s PR firm had arranged it: a prestigious piece of marketing for a relatively new brand—and the unfamiliar guy behind it.

Though a son of the Hitt Contracting family—one of Washington’s wealthiest construction dynasties—Todd Hitt had only recently forged a profile as a brash and crazy-successful self-made entrepreneur. He was a commentator on Fox Business. He traveled by private jet. By the night of the soiree, he had convinced a long list of locals that he was an alum of the Wharton business school; that he had a personal net worth in the billions; that when he wasn’t busy with his own exploits, he quietly helped run the family company, too.

Thanks to Hitt’s platinum-plated last name—the one that built the new Glenstone museum, part of Nationals Park, the W Hotel downtown, and NASA’s headquarters—the persona had been a remarkably easy sell. In reality, though, it was a sordid mirage.

Even as Hitt worked the room during Washington’s most glittery weekend, he had yet to pony up for the party—and he never would. Not two months later, he would become the target of a federal criminal investigation. By fall, the FBI would unmask Kiddar Capital as a multimillion-dollar Ponzi scheme and rebrand Hitt as a shameless con man.

The society types who’d found themselves taken with this charismatic new player were aghast. Hitt had stolen from nearly two dozen victims, including some in the upper echelons of Washington’s real-estate community, and stiffed many others. But he was hardly your typical grifter who had to hustle to make a buck. Not even close. Hitt’s grandparents had launched the family business from their dining-room table in Arlington in 1937. His father, Russell, helped expand it into one of the highest-earning general contractors in the country. Todd Hitt was born already having it all. He apparently just wanted more.

Todd Hitt the billionaire businessman was incarnated some five years ago when, seemingly overnight, he popped up as a real-estate developer—having spent much of the prior decade as a soccer coach.

He had been a bit of a wanderer professionally. Unlike his older brother, Brett, who’d climbed the ranks at Hitt Contracting, Todd Hitt had never worked for the family company. He’d built spec houses around the same North Arlington neighborhoods where he’d grown up, but according to a court document, his homebuilding business had collapsed. He’d been coaching since at least the mid-’90s and had founded an elite high-school soccer club in Reston. But now solidly into midlife, Hitt suddenly seemed eager to leave his fingerprints on the Washington landscape, the way his family had.

By the summer of 2014, Hitt, then 49 years old, was putting together his first major real-estate deal, targeting a prime but underdeveloped corner in downtown Falls Church, where an Applebee’s restaurant stood. The market may have been small, but it was ripe for an ambitious new vision—and more to the point, an ambitious new visionary. Hitt attached himself to an impressive partner, Insight Property Group, the developer behind projects such as the Apollo/Whole Foods complex on DC’s H Street, Northeast. They imagined building more than 70,000 square feet of trophy office space as well as a state-of-the-art home for the local theater Creative Cauldron. The sleepy site, Hitt said, would turn into a commercial hub by day and a cultural destination by night. “It was all very exciting,” says Creative Cauldron’s founder, Laura Connors Hull.

“A lot of people’s eyes rolled through the back of their heads. They were just stunned.”

Pivoting from travel-soccer coach to commercial developer might sound like a leap. But Hitt was never known to lack nerve. “He always had a self-confidence that, when you don’t have it, it irritates you,” says Quentin Paquette, who met Hitt in second grade and played soccer with him at Arlington’s Yorktown High School. Their coach, Jean-Pierre Bell, remembers: “You had to remind Todd that he was not the boss—I was the boss.”

Hitt didn’t waste time letting folks know he’d arrived. He began alerting the Falls Church News-Press to his moves around town; flattering stories would then appear, describing Hitt’s ideas for more local development. “He comes with the name. Everybody was impressed by that,” says the newspaper’s owner and editor, Nicholas Benton. “He presented himself as the top dog in Falls Church.” Not only that—Hitt was also touting purported projects in Denver, Miami, Puerto Rico, and other locales. “I’m a dealmaker,” he said.

Soon, there was a more audacious evolution: He was getting into the clubby private-equity business. In 2016, Hitt launched Kiddar Capital, opened an office in Falls Church, and began courting investors. His pitches, typically aimed at acquaintances and friends, were often done over dinner or drinks. “To go out to happy hour with Todd,” recalls one former friend, “you were probably either an investor or a target.”

Hitt would promise he had his own “skin in the game,” according to court documents, to demonstrate his confidence. He’d also toss around the family name. According to a former Kiddar employee, the boss’s messaging boiled down to: “I’m Todd Hitt. I’m a billionaire. My family’s got this huge company. Trust me.”

Many savvy people did, including Washington real-estate executives such as Insight Property’s CEO, Richard Hausler; William Quinby, vice chairman at the commercial brokerage Savills; and Brendan Owen, a chairman at the real-estate advisory Newmark Knight Frank. “The reason I invested is the Hitt name,” says a local lobbyist. “The signs are all over the city. I thought, ‘How could this be bad?’ ”

For one of Kiddar’s first major plays, Hitt targeted Washington’s expanding tech scene, committing $2 million to a new company called Aquicore. Not long after that, he was raising $6 million to buy nearly five acres at the future site of the Silver Line Metro stop in Herndon—a potentially transformative project for the region. “ ‘Take a look at this Herndon deal. It’s going to be a home run.’ He said some version of that to me several times,” recalls the former friend.

Within a couple of years, Hitt was operating like a heavy. When the Capitals played in the Eastern Conference semifinals in 2016, he flew his staff to Pittsburgh on a private jet. There were courtside Wizards seats and invitations to his Nats suite. Some Kiddar employees got new wardrobes worth thousands of dollars. He upgraded from a Chevy Tahoe to a Mercedes-Benz SUV and was often chauffeured by his private driver in a Benz sedan. Around the office, he was rumored to be having a Maybach custom-built.

It’s not as if luxury cars have much currency in Washington, though. So to be taken seriously by people who might do business with him, Hitt and his staff became fixtures on the charity circuit. “I lived at those events,” says the former employee. “It was all about building up the image.”

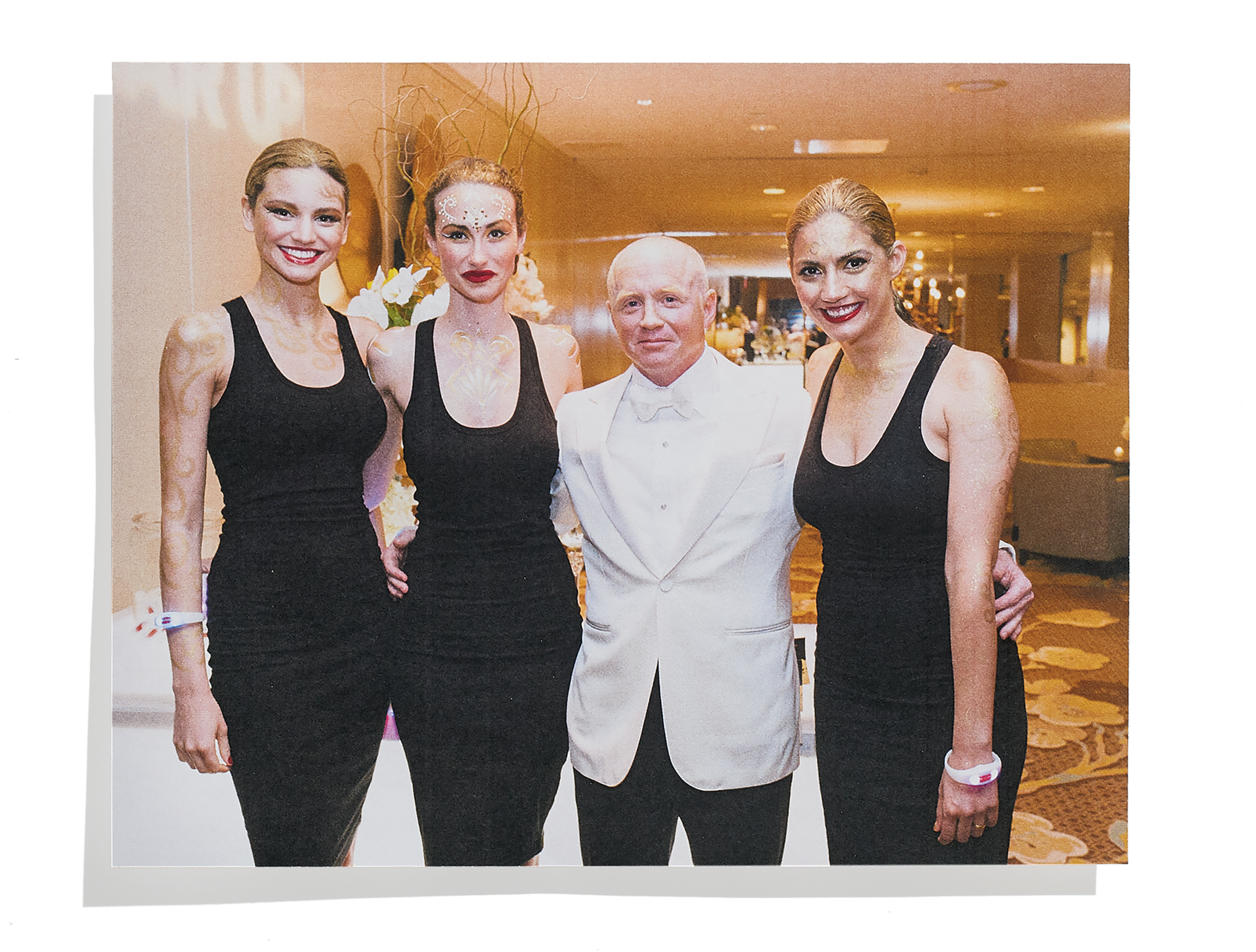

Hitt would also jet out of town for paparazzi-attended parties in the Hamptons and Los Angeles, accompanied by his mistress Michelle Dolansky, a childhood friend he knew from the soccer world. (They were photographed together all over the country, their relationship an open secret.) Though small in stature, maybe five and a half feet tall, Hitt knew how to consume a room. He dressed for the spotlight, sporting showy wide-lapel suits, sometimes with his aviator sunglasses on indoors.

One year, he donned a white dinner jacket and threw a glitzy bash of his own, called Kiddar After Hours. The venue was the Georgetown Four Seasons, and the honorees were local arts organizations including the Phillips Collection and Wolf Trap. Models passed Champagne, the bars were stocked with Pappy Van Winkle, and Dominican hand-rolled cigars were free for the taking. Hitt invited tech execs, real-estate types, and philanthropists—or as the ex-employee puts it: “Everyone around town who he wanted to think he had a lot of money.”

Hitt had a way of making any public gesture flamboyant. Once, for an Alexandria nonprofit that runs preschools for low-income kids, he donated $25,000—via tweet. When Steve Messeh, executive director of the youth-focused nonprofit Hope Multiplied, heard from a friend that Hitt was someone who could become a significant donor, Messeh invited him to the group’s annual gala and placed him at a VIP table. After one of Hitt’s high-roller seatmates egged him on, Hitt pledged $50,000 on the spot—and informed Messeh that he could broadcast the donation to the crowd. “A lot of people that give to the organization give anonymously,” says Messeh. “He was the opposite.”

The showmanship reaped dividends. In 2018, Washington Life magazine put Hitt on the cover of its philanthropy issue alongside Carrie Marriott and Cindy Jones, feting them as some of “Washington’s most generous givers.” “When we showed up to the photo shoot, [Carrie and I] said to each other, ‘Wow, we don’t even know Todd,’ ” recalls Jones, who was then board president of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. “He emerged on the scene quite quickly, donating a lot of money. It was kind of unusual.”

After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, Craft Media, the PR firm that repped Kiddar Capital, suggested that Hitt could use his private jet to help. Craft’s CEO contacted Puerto Rico’s former governor Luis Fortuño, now a partner in the DC office of Steptoe & Johnson, who’d been in the press publicizing the desperate need for aid. Hitt and Fortuño flew to Puerto Rico and visited the Ronald McDonald House and a children’s hospital. At some point, they ran into José Andrés, the celebrity chef who became a national hero for feeding thousands after the storm. Within days, Kiddar Capital supplied photos of Andrés, Fortuño, and Hitt to accompany feel-good stories in the Washington Business Journal and the Falls Church News-Press. The latter referred to both Andrés and Fortuño as Hitt’s longtime friends. Through spokespeople, both told me the trip was the only time they’d ever met him.

As Hitt’s profile rose, his former business partner Dave Mark watched, awestruck. The two had been neighbors in Arlington and, along with their families, had become close. Sometime around 2011, Mark says Hitt approached him with a proposal that they go in on real estate together. Hitt subsequently formed an investment shop called Kiddar Metz, a blend of their children’s initials.

Over the next few years, Mark says he gave Hitt increasing amounts of money for properties Hitt said he was buying: “Todd would say, ‘You need it back in a year? You’ll get it back in a year.’ ” But the returns never materialized. By 2014, Mark and his wife had grown frustrated, and Mark told Hitt he wanted out. Though disappointed that his investments weren’t paying off, Mark says he wasn’t angry.

Then a couple of years later, Hitt rebranded Kiddar Metz as Kiddar Capital, moved into a real office with a real staff, and seemingly began to enjoy wild success. “I thought it was a weakness in me,” Mark says. “I felt like he was doing amazingly well and I missed the boat on it.”

Other people who’d known previous incarnations of Hitt had even less charmed experiences. In the early 2000s, Lindsay Bowers played on one of the teams in Hitt’s Reston Football Club. She lodged a complaint with the Virginia Youth Soccer Association alleging that Hitt was verbally abusive. According to disciplinary documents from the case, then-17-year-old Bowers said she’d been joking around with a teammate during practice when Coach Hitt shouted at her: “Get off my training field, you f—ing c—!”

As part of the same proceeding, a male player, Garrett Patrick, alleged that Hitt mistakenly thought Patrick had rolled his eyes at him during a warmup, then got “inches away” from Patrick’s face and screamed: “If you roll your eyes at me again, I’ll f— you up, f— your family over, and f—ing knock the teeth to the back of your throat. You’ll be in the hospital for so long you won’t even know it.” (Patrick could not be reached. During the case, his mother backed up his account.)

When Hitt testified before the league adjudicators in 2005, he admitted to yelling at Bowers but claimed he’d said, “Get your shit and get the f— off my training field!” He added that he’d then mumbled to himself: “F—ing twat, what am I doing this for?”

Hitt was punished, but only briefly. The league suspended him from coaching for six months. After completing a conflict-resolution program, he was allowed back—and continued coaching for several more years.

Bowers, who still lives in Washington and is now 33, has a theory for why her old coach never lost his status among the hypercompetitive parents in the local travel-soccer scene. When Hitt was their kids’ age, he’d been one of the hottest college prospects in the nation, then suited up all four years for UVA. “He would talk about how many connections he had, all the people he knew, how helpful he could be,” says Bowers. “He never let us forget that everybody knew who he was.”

By the time Hitt had reinvented himself as a financier and civic patron, many of his lies would have been easy enough to disprove—such as the one about going to Wharton, which took me less than an hour of e-mailing with the school to debunk. Yet through a combination of cunning, luck, and the credibility that came with his last name, Hitt was able to keep up the illusion.

In 2016, for instance, when Kiddar Capital was supposed to deliver the second half of its $2-million investment in Aquicore, the tech startup, Hitt refused to pay—unbeknownst to his investors. According to a source within Aquicore, Hitt called just before the money was due—purportedly after disembarking from his private plane in England, where he was seeing a soccer game—and pulled an about-face virtually unheard of in the venture-capital world. Even though he had agreed to the terms, he said he’d simply changed his mind about the investment. “There had already been an impression around the table that he was not a mature or sophisticated investor,” says the source. “That validated the suspicion.” Yet given the company’s then-fledgling status, Aquicore decided it wasn’t worth the trouble to chase down the debt. Hitt’s investors remained in the dark.

Messeh, the leader of the youth charity that Hitt had offered $50,000 on the spot, was stiffed and then strung along in a ten-month game of cat-and-mouse over the money. In the middle of it, a Kiddar employee asked Messeh to participate in a photo shoot for a Washington Life ad the firm was buying to coincide with Hitt’s philanthropy cover. For the ad, Hitt wanted to assemble a group photo showing off all the nonprofits he’d supported. Messeh was blown away by the request. Still, after consulting his board, they all decided he should do it, in hopes that the favor would shake loose the $50,000.

On the day of the shoot, at the Washington Golf and Country Club in North Arlington, Hitt spotted Messeh talking to the other charity executives, Messeh says, and “literally made a beeline for me and told me the check is coming any day now.” In hindsight, Messeh speculates Hitt was running interference, trying to keep Messeh from telling the others he’d yet to receive his donation. It worked—Messeh kept quiet, still hoping the check would materialize.

Kiddar employees saw all manner of oddities and didn’t speak up, either. The firm’s website boasted of offices in Houston, London, and Palm Springs—none of which any of the staff had ever seen or communicated with. Their boss’s personal life was also mystifying. They’d seen his wife, Susan, drop by the office, as well as his mistress, Michelle. (During Michelle Dolansky’s protracted divorce battle with her ex-husband, she claimed emotional abuse, while he claimed that her years-long affair with Hitt had “ruined” their family. Dolansky declined to comment for this story. The judge overseeing the case attributed the breakdown of the marriage to Hitt and Dolansky’s relationship.)

Most troubling to the staff was that Hitt struggled to make payroll on time. Some months, people would get their checks a few days late. Other times, not at all, so that Hitt wound up having to give them double the next pay period. “In times like that,” says a former employee, “he would just disappear.”

Still, they put up with it—they were a small team of mostly twenty- and thirtysomethings, young and relatively inexperienced. About half, including two of Hitt’s daughters, were focused on marketing. The head of investor relations was an ex–suit salesman from Zegna, where Hitt had been one of his best customers.

“You can’t imagine the sense of betrayal I feel. It’s like a burning hole in my gut.”

When pay was late, there often wasn’t a bookkeeper to talk to—Kiddar didn’t employ one full-time. Even if Hitt was around, staffers weren’t eager to confront him. “A lot of people had a fear of him,” says the former employee. For the most part, everyone figured he was good for the money anyway. He was constantly reminding them he was a billionaire. And, they thought, he had a far more established business behind him: Hitt often wouldn’t appear at Kiddar’s offices until lunchtime because, he told them, he spent his mornings working at Hitt Contracting.

Thursday morning, September 20, 2018, some of Kiddar’s employees were already in the office when a startling goodbye e-mail from the boss popped up in their in-boxes: They were being fired. By that afternoon, Kiddar Capital was dark and locked up.

It had been a strange few months. On the one hand, Hitt had been his usual peacocking self, schmoozing at the White House Correspondents’ party, sponsoring a black-tie dinner for former General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross. Hitt had also just launched a next-level growth strategy for the firm, announcing that he was preparing to size up and go after institutional money.

Yet employees had witnessed an unsettling sequence of events behind the scenes. Hitt had hired a pair of employees to help bring the firm into SEC compliance so it could become the larger operation he was describing. But after only a month, they vanished. Soon, a team of lawyers was in the office, asking for documents and backing up computers, for reasons that were unclear. Around the same time, investors in the Silver Line property were getting anxious, asking for financial updates.

“All the employees were like, ‘Oh, my God—what’s going on?’ ” says a former staffer. “We knew Mr. Hitt was in trouble, but we didn’t know exactly the reason Mr. Hitt was in trouble.”

Barely two weeks after the mass firing, the explanation was all over the news.

Hitt had surrendered to authorities and was being indicted on eight counts of securities fraud. Throughout the charging documents, the fingerprints of two informants appeared: “Employee A” and “Employee B.”

Hitt’s new hires, it was suddenly clear, had packed up and gone straight to the FBI. Hitt had recruited them to build up the firm, and instead they had taken it down.

According to court documents, what first spooked them was Hitt’s reluctance to show them the books. Given the nature of their jobs, they’d expected to have access to the firm’s full financial picture, yet he wouldn’t budge. Puzzling together what they could, they realized Hitt’s boasts that Kiddar had $1.4 billion in assets under management were ludicrously inflated. It looked to them as if the real number was closer to $27 million.

With a little more digging, authorities uncovered a pretty amateur scheme. For instance, with Aquicore—though Hitt had told the tech company he simply didn’t want to invest the second million with them, the truth, according to court documents, was that he’d blown those investor funds on other costs, including Kiddar’s overhead and a $2-million house he’d built on spec in McLean.

His Herndon Silver Line project became a sort of personal piggy bank. Hitt raised nearly $8 million more than he needed for the deal and then used some of the extra to pay down his staggering credit-card tabs—$111,151 in Wizards and Caps charges, $59,220 at the jeweler Bulgari, $11,462 at the Inn at Perry Cabin on the Eastern Shore, $2,897 at the Four Seasons in Georgetown, upward of $86,000 in private-jet rentals and travel, and various other expenses.

And it turned out that for all his talk of “skin in the game,” he had none of his own money invested. (Hitt declined multiple requests to be interviewed.)

When news of the fraud hit, says Nicholas Benton, the Falls Church newspaper owner, “A lot of people’s eyes rolled through the back of their heads. They were just stunned.”

Cindy Jones, the philanthropist who had shared the Washington Life cover with Hitt and Carrie Marriott, felt the same way. “I was absolutely shocked,” she says. “To be honest with you, Carrie and I were both sort of appalled. It was disappointing. You don’t even want to be associated with somebody like that.”

By the morning of his sentencing, on a blustery day last June, Hitt had already lost both the Arlington home he shared with his wife and daughters and the Mosaic-district townhouse he’d kept with his girlfriend. Even so, he still looked the part he’d played for years, in an immaculately tailored suit, pumping hands as though he’d just arrived at his retirement party. “Hey, guys! Thanks for coming,” he greeted some friends outside Courtroom 700. “Your sister know you’re here? You look good!”

The wreckage that Hitt wrought is breathtaking: Twenty-one investors say they lost more than $27 million combined. On top of that, Hitt’s employees, vendors, lenders, and charities he’d pledged to support, among others, claim they’re out almost $59 million. The duped include the Washington Ballet, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, Halcyon House, the Smithsonian, Hope Multiplied (which never got its $50,000), and Craft Media, the PR firm that helped Hitt cultivate his image.

Other damage is harder to quantify. Such as the stalled revival of Broad and Washington streets, where Hitt made his splashy entrée into Falls Church. The corner remains occupied by two rundown office buildings and the Applebee’s—just as it was back in 2014 when Hitt was first spinning himself as the area’s real-estate savior. It turned out he never really had a personal stake in the property; according to court documents, he covered his share with funds from investors.

“I wish I could see inside his brain to understand how somebody could do the things he did,” says Dave Mark, Hitt’s former neighbor and business partner, who claims in court papers that Hitt owes him more than $1 million. “You can’t imagine the sense of betrayal I feel. It’s like a burning hole in my gut.”

Before the sentencing, Hitt’s family sent letters to the judge alluding to reasons why he may have strayed. Hitt’s sister Tracy Millar told the judge that alcoholism runs in the Hitt family and implied that mental illness was to blame for her brother’s actions. His sister Jodi Nash leaned heavily on other family pathologies, describing how tough it had been for Hitt after his college soccer career ended and he didn’t find a role in the family company: “With my dad, brother Brett, and brother-in-law Jim Millar driving dynamic business growth at Hitt company, and Todd’s hyper competitiveness in achieving recognition in the business world, he struggled transitioning,” she wrote, asking for leniency.

Hitt’s wife described a fractious dynamic among the Hitt men: “I watched how the male members of [Todd’s] family treated him and have admired how he has dealt with it through the years, despite not receiving proper recognition for his accomplishments. . . . His father and brother were jealous of his talents and sought to undermine him at every turn.” (Russell and Brett Hitt wrote brief, generally supportive letters. Through their lawyer, Hitt’s siblings and parents declined to comment. His wife also declined to comment.)

Or maybe it was soccer’s fault. In her letter, Hitt’s wife also wrote that her husband had been diagnosed with “a succession of mild traumatic brain injuries from all his years of playing,” which she said his doctor had warned could cause “erratic behavior.”

Would this depiction of Hitt cause the judge to soften? In fact, Hitt’s lawyers had already cut a deal. He had been unusually cooperative with authorities—immediately confessing when he discovered he was under investigation and even volunteering new evidence. What’s more, his family, apparently able to look past how he’d dragged their name through more mud than you’d find on one of their construction sites, had agreed to give the government $20 million to help repay his victims. As a result, prosecutors had joined Hitt’s defense in asking the judge to give him six and a half years of jail time for pleading guilty to one count of securities fraud. Not exactly a light penalty, but less than the possible maximum of 20 years.

All that remained was for Judge Leonie Brinkema to hear from Hitt himself, then decide whether to go along with the terms.

Hitt took the podium that morning as a swath of relatives looked on. “I’m deeply sorry for the pain I’ve caused my entire large, loving family,” he said, the exuberance drained from his tone. “I apologize to the investors, friends, business associates, all my employees, who I cared a great deal about. . . . It’s going to take me some time to fully understand how and why I did this, but I’ll spend my incarcerated time and probationary time and, in fact, the rest of my life contemplating this and seeking, in my own way, redemption.”

By this point, Hitt had racked up a lot of practice convincing smart people to believe in him—useful experience, perhaps. After he finished speaking, Judge Brinkema announced that indeed six and a half years behind bars would do. “You’re not the first good person,” she said, “who’s done bad things.”

Correction: A previous version of this story said the Washington Capitals played in the Eastern Conference finals in 2016. The team reached the Eastern Conference semifinals, but they lost to the Pittsburgh Penguins.

This article appears in the February 2020 issue of Washingtonian.