About Coronavirus 2020

Washingtonian is keeping you up to date on the coronavirus around DC.

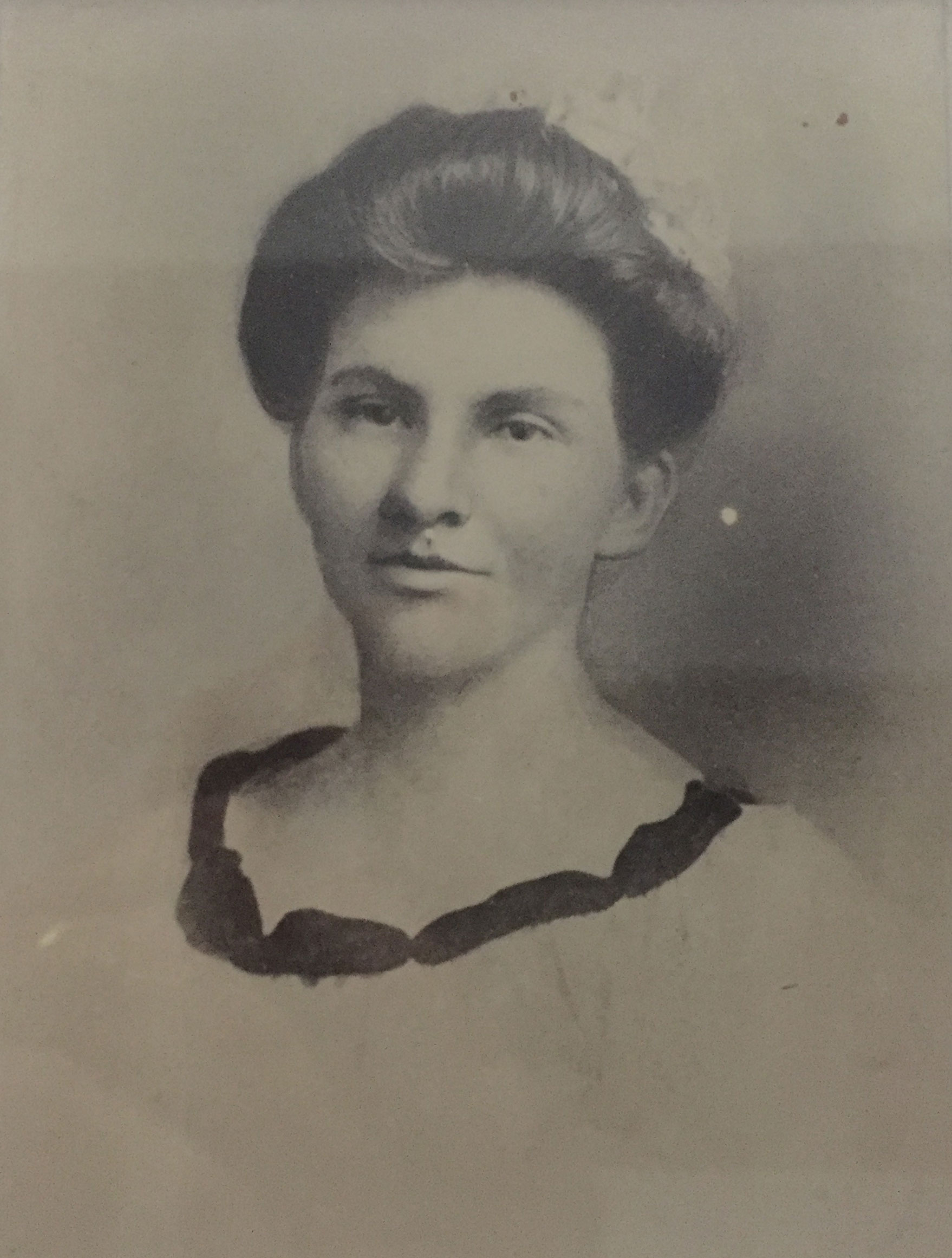

A portrait of my grandmother hung over the mantle in my grandfather’s house for decades. Something about that portrait demanded attention. My grandmother, Pearl Cox Hightower, looked eternally young and healthy, with long hair swept up Gibson Girl–style. She died on October 16, 1918, age 38, in the flu pandemic. She was a few months pregnant.

My mother was not quite four. The family lived in comfort on a small estate in Athens, Alabama. My mother said her father had caught the virus from one of the customers at his dry-goods store. My grandmother nursed him back to health, then she caught the virus and died.

Growing up, my sister and I heard this story often.

“The servants went through the house,” she told us. “They stopped all the clocks. They turned the mirrors to the walls. Daddy wouldn’t let us go to the funeral, or to anyone’s funeral after that. My mother’s clothes were packed away in a trunk we were forbidden to open. The family was devastated.”

My mother lived a long, full life and was active into her nineties. The year she turned 90, my sister and I interviewed her, typing up a transcript as part of her birthday celebration. During this spring’s coronavirus quarantine, I read those interviews for the first time in years.

Now I understand why my mother idolized her father. In our conversations, she told me her greatest fear as a young girl had been that her father would die and leave her orphaned. She never forgot his actions after her mother’s death. He gathered up his three children—my mother was the youngest—and moved their beds into his room so no one would wake up alone and afraid. He read them stories every night, any story except Cinderella, because he didn’t want them to hear about wicked stepmothers. He promised them that if he married again, it would be to a woman without children or an ex-husband. My grandfather brought his parents to live with the family and help raise his kids.

He did remarry a few years later—a childless woman whose husband had died of the flu. However, his first wife’s spirit and her portrait dominated the homeplace. My grandmother’s will had left the family house to her three children, giving my grandfather the right to live in it for the rest of his life.

We visited him most summers. Every year, I heard him tell my mother, “When I look at you or your brother or sister, I always think of your mother.”

In my interview with her, my mother told me that as a child she often asked her siblings to tell her what they remembered about their mother.

“They couldn’t remember anything,” she said. “I guess it was too painful. None of my friends lost their mother or father in the flu epidemic, but I did.”

I recall many fun times with my grandfather and aunt and uncle. But I also recall my grandmother’s portrait, and the grief the family carried.

The year after my mother turned 90, I read John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. I sent her the book, and when I next saw her, we talked about it. I mentioned Barry’s observation that when the epidemic ended, everyone seemed to forget about it.

My mother looked at me and said, “I didn’t forget.”

Arch Campbell was an entertainment reporter in Washington for 40 years with NBC4 and WJLA/News Channel 8. He now cohosts the podcast At the Movies With Arch Campbell, Jen Chaney & Loo Katz, currently reviewing cable, streaming, and online films.