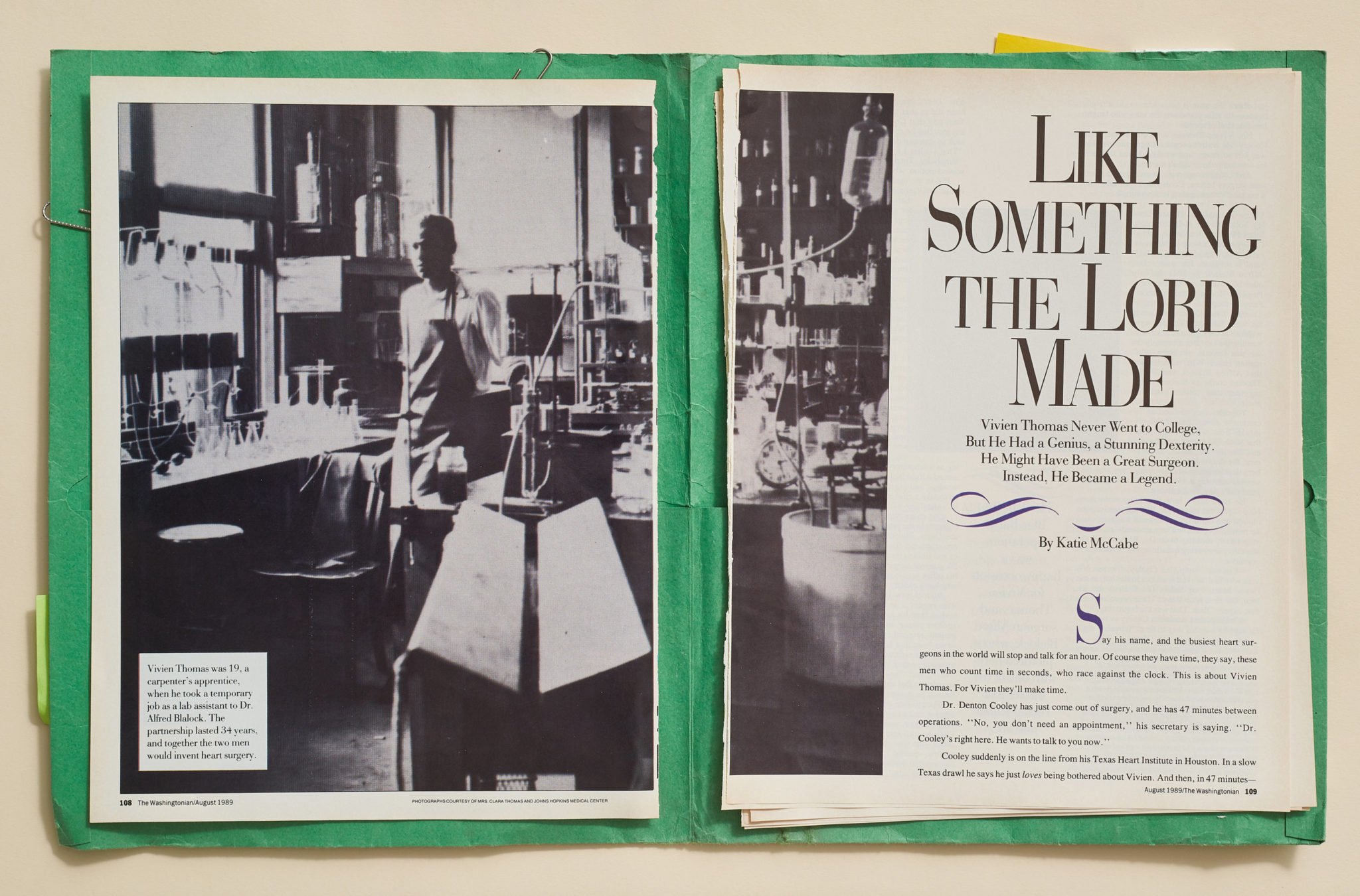

In 1989, Washingtonian published what might be the most popular article in its history. “Like Something the Lord Made,” by Katie McCabe, tells of Vivien Thomas, an African American lab assistant to white surgeon Alfred Blalock from the 1930s to the ’60s. Thomas hadn’t gone to college, let alone medical school, but through their pioneering work together, the two men essentially invented cardiac surgery. The story of Thomas’s unlikely and inspiring journey won a National Magazine Award for feature writing and became an Emmy Award–winning HBO movie starring Mos Def. Read it here and raise a glass to lifesaving medical professionals everywhere—with or without an MD.

Say his name, and the busiest heart surgeons in the world will stop and talk for an hour. Of course they have time, they say, these men who count time in seconds, who race against the clock. This is about Vivien Thomas. For Vivien they’ll make time.

Dr. Denton Cooley has just come out of surgery, and he has 47 minutes between operations. “No, you don’t need an appointment,” his secretary is saying. “Dr. Cooley’s right here. He wants to talk to you now.”

Cooley suddenly is on the line from his Texas Heart Institute in Houston. In a slow Texas drawl he says he just loves being bothered about Vivien. And then, in 47 minutes—just about the time it takes him to do a triple bypass—he tells you about the man who taught him that kind of speed.

No, Vivien Thomas wasn’t a doctor, says Cooley. He wasn’t even a college graduate. He was just so smart, and so skilled, and so much his own man, that it didn’t matter.

And could he operate. Even if you’d never seen surgery before, Cooley says, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple.

Vivien Thomas and Denton Cooley both arrived at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1940— Cooley to begin work on his medical degree, Thomas to run the hospital’s surgical lab under Dr. Alfred Blalock. In 1941 the only other black employees at the Johns Hopkins Hospital were janitors. People stopped and stared at Thomas, flying down corridors in his white lab coat. Visitors’ eyes widened at the sight of a black man running the lab. But ultimately the fact that Thomas was black didn’t matter, either. What mattered was that Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas could do historic things together that neither could do alone.

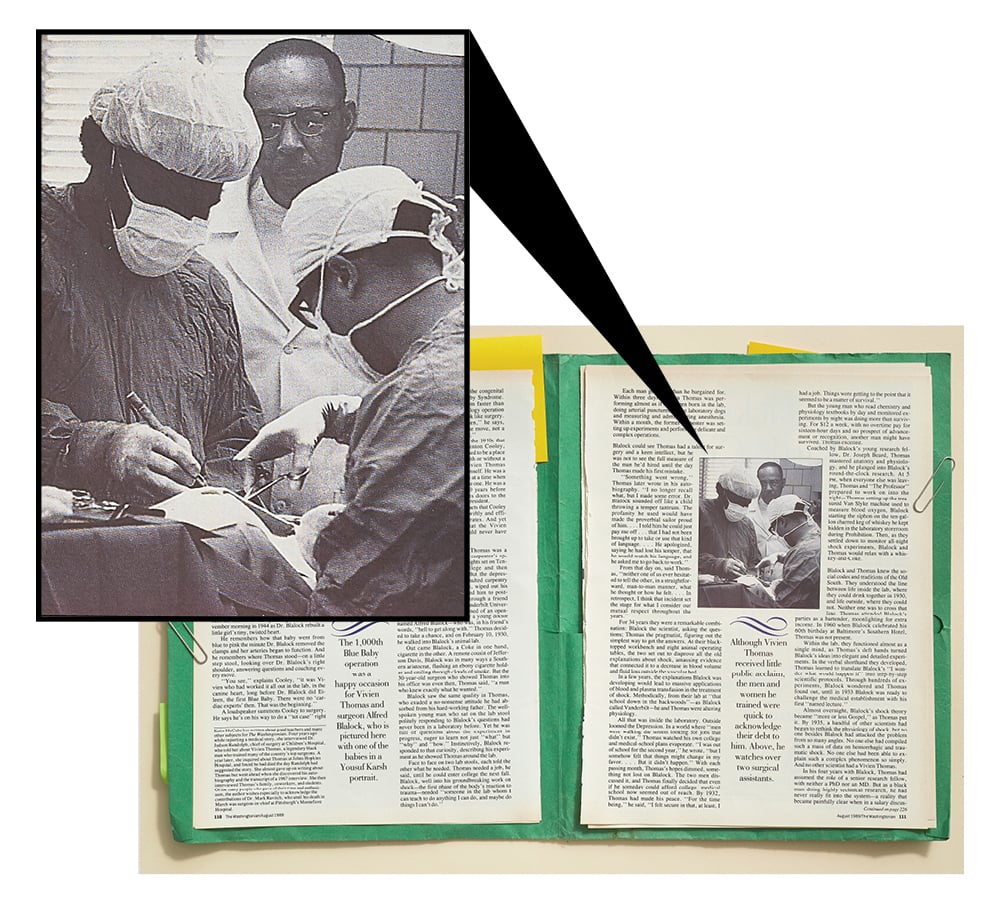

Together they devised an operation to save “Blue Babies”— infants born with a heart defect that sends blood past their lungs— and Cooley was there, as an intern, for the first one. He remembers the tension in the operating room that November morning in 1944 as Dr. Blalock rebuilt a little girl’s tiny, twisted heart.

He remembers how that baby went from blue to pink the minute Dr. Blalock removed the clamps and her arteries began to function. And he remembers where Thomas stood—on a little step stool, looking over Dr. Blalock’s right shoulder, answering questions and coaching every move.

“You see,” explains Cooley, “it was Vivien who had worked it all out in the lab, in the canine heart, long before Dr. Blalock did Eileen, the first Blue Baby. There were no ‘cardiac experts’ then. That was the beginning.”

A loudspeaker summons Cooley to surgery. He says he’s on his way to do a “tet case” right now. That’s tetralogy of Fallot, the congenital heart defect that causes Blue Baby Syndrome. They say that Cooley does them faster than anyone, that he can make a tetralogy operation look so simple it doesn’t even look like surgery. “That’s what I took from Vivien,” he says, “simplicity. There wasn’t a false move, not a wasted motion, when he operated.”

But in the medical world of the 1940s that chose and trained men like Denton Cooley, there wasn’t supposed to be a place for a black man, with or without a degree. Still, Vivien Thomas made a place for himself. He was a teacher to surgeons at a time when he could not become one. He was a cardiac pioneer 30 years before Hopkins opened its doors to the first black surgical resident.

Those are the facts that Cooley has laid out, as swiftly and efficiently as he operates. And yet history argues that the Vivien Thomas story could never have happened.

In 1930, Vivien Thomas was a nineteen-year-old carpenter’s apprentice with his sights set on Tennessee State College and then medical school. But the depression, which had halted carpentry work in Nashville, wiped out his savings and forced him to postpone college. Through a friend who worked at Vanderbilt University, Thomas learned of an opening as a laboratory assistant for a young doctor named Alfred Blalock—who was, in his friend’s words, “hell to get along with.” Thomas decided to take a chance, and on February 10, 1930, he walked into Blalock’s animal lab.

Out came Blalock, a Coke in one hand, cigarette in the other. A remote cousin of Jefferson Davis, Blalock was in many ways a Southern aristocrat, flashing an ebony cigarette holder and smiling through clouds of smoke. But the 30-year-old surgeon who showed Thomas into his office was even then, Thomas said, “a man who knew exactly what he wanted.”

Blalock saw the same quality in Thomas, who exuded a no-nonsense attitude he had absorbed from his hard-working father. The well-spoken young man who sat on the lab stool politely responding to Blalock’s questions had never been in a laboratory before. Yet he was full of questions about the experiment in progress, eager to learn not just “what” but “why” and “how.” Instinctively, Blalock responded to that curiosity, describing his experiment as he showed Thomas around the lab.

Face to face on two lab stools, each told the other what he needed. Thomas needed a job, he said, until he could enter college the next fall. Blalock, well into his groundbreaking work on shock—the first phase of the body’s reaction to trauma—needed “someone in the lab whom I can teach to do anything I can do, and maybe do things I can’t do.”

Each man got more than he bargained for. Within three days, Vivien Thomas was performing almost as if he’d been born in the lab, doing arterial punctures on the laboratory dogs and measuring and administering anesthesia. Within a month, the former carpenter was setting up experiments and performing delicate and complex operations.

Blalock could see Thomas had a talent for surgery and a keen intellect, but he was not to see the full measure of the man he’d hired until the day Thomas made his first mistake.

“Something went wrong,” Thomas later wrote in his autobiography. “I no longer recall what, but I made some error. Dr. Blalock sounded off like a child throwing a temper tantrum. The profanity he used would have made the proverbial sailor proud of him. . . . I told him he could just pay me off . . . that I had not been brought up to take or use that kind of language. . . . He apologized, saying he had lost his temper, that he would watch his language, and he asked me to go back to work.”

From that day on, said Thomas, “neither one of us ever hesitated to tell the other, in a straightforward, man-to-man manner, what he thought or how he felt. . . . In retrospect, I think that incident set the stage for what I consider our mutual respect throughout the years.”

For 34 years they were a remarkable combination: Blalock the scientist, asking the questions; Thomas the pragmatist, figuring out the simplest way to get the answers. At their black-topped workbench and eight animal operating tables, the two set out to disprove all the old explanations about shock, amassing evidence that connected it to a decrease in blood volume and fluid loss outside the vascular bed.

In a few years, the explanations Blalock was developing would lead to massive applications of blood and plasma transfusion in the treatment of shock. Methodically, from their lab at “that school down in the backwoods”—as Blalock called Vanderbilt—he and Thomas were altering physiology.

All that was inside the laboratory. Outside loomed the Depression. In a world where “men were walking the streets looking for jobs that didn’t exist,” Thomas watched his own college and medical-school plans evaporate. “I was out of school for the second year,” he wrote, ‘ ‘but I somehow felt that things might change in my favor. . . . But it didn’t happen.” With each passing month, Thomas’s hopes dimmed, something not lost on Blalock. The two men discussed it, and Thomas finally decided that even if he someday could afford college, medical school now seemed out of reach. By 1932, Thomas had made his peace. “For the time being,” he said, “I felt secure in that, at least, I had a job. Things were getting to the point that it seemed to be a matter of survival.”

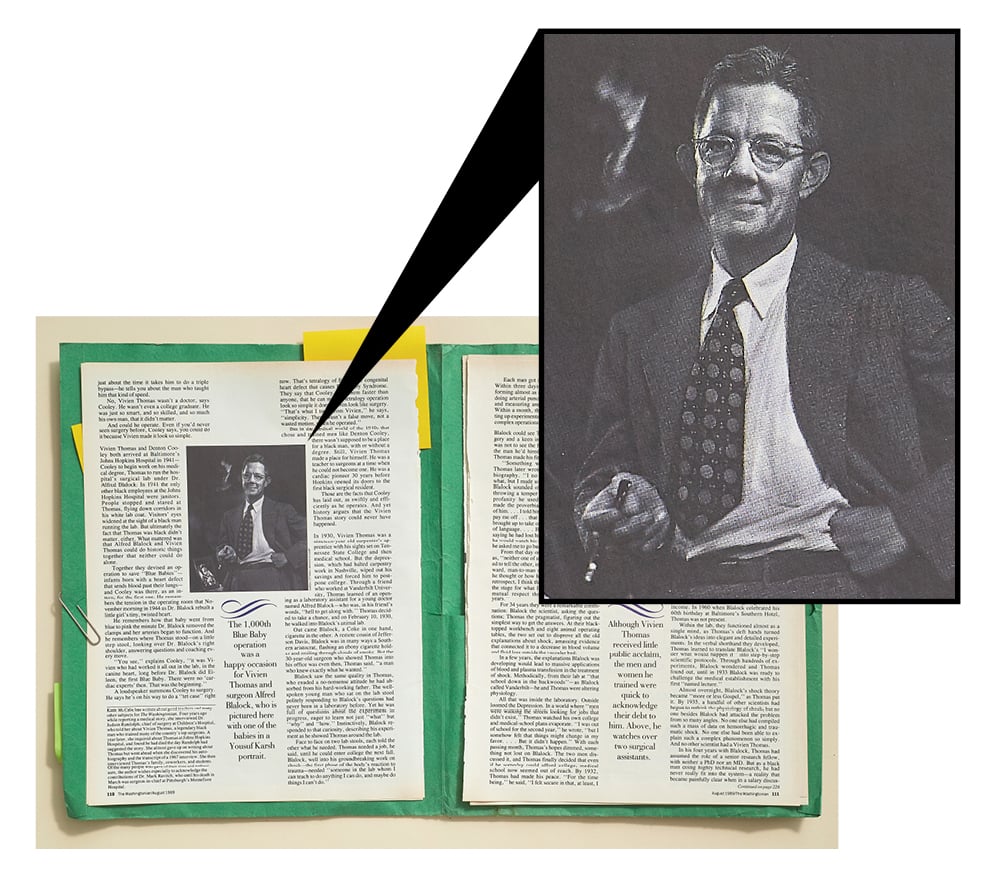

But the young man who read chemistry and physiology textbooks by day and monitored experiments by night was doing more than surviving. For $12 a week, with no overtime pay for sixteen-hour days and no prospect of advancement or recognition, another man might have survived. Thomas excelled.

Coached by Blalock’s young research fellow, Dr. Joseph Beard, Thomas mastered anatomy and physiology, and he plunged into Blalock’s round-the-clock research. At 5 PM, when everyone else was leaving, Thomas and “The Professor” prepared to work on into the night—Thomas setting up the treasured Van Slyke machine used to measure blood oxygen, Blalock starting the siphon on the ten-gallon charred keg of whiskey he kept hidden in the laboratory storeroom during Prohibition. Then, as they settled down to monitor all-night shock experiments, Blalock and Thomas would relax with a whiskey-and-Coke.

Blalock and Thomas knew the social codes and traditions of the Old South. They understood the line between life inside the lab, where they could drink together in 1930, and life outside, where they could not. Neither one was to cross that line. Thomas attended Blalock’s parties as a bartender, moonlighting for extra income. In 1960 when Blalock celebrated his 60th birthday at Baltimore’s Southern Hotel, Thomas was not present.

Within the lab, they functioned almost as a single mind, as Thomas’s deft hands turned Blalock’s ideas into elegant and detailed experiments. In the verbal shorthand they developed, Thomas learned to translate Blalock’s “I wonder what would happen if” into step-by-step scientific protocols. Through hundreds of experiments, Blalock wondered and Thomas found out, until in 1933 Blalock was ready to challenge the medical establishment with his first “named lecture.”

Almost overnight, Blalock’s shock theory became “more or less Gospel,” as Thomas put it. By 1935, a handful of other scientists had begun to rethink the physiology of shock, but no one besides Blalock had attacked the problem from so many angles. No one else had compiled such a mass of data on hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. No one else had been able to explain such a complex phenomenon so simply. And no other scientist had a Vivien Thomas.

In his four years with Blalock, Thomas had assumed the role of a senior research fellow, with neither a PhD nor an MD. But as a black man doing highly technical research, he had never really fit into the system—a reality that became painfully clear when in a salary discussion with a black coworker, Thomas discovered that Vanderbilt classified him as a janitor.

He was careful but firm when he approached Blalock on the issue: “I told Dr. Blalock . . . that for the type of work I was doing, I felt I should be . . . put on the pay scale of a technician, which I was pretty sure was higher than janitor pay.”

Blalock promised to investigate. After that, “nothing more was ever said about the matter,” Thomas recalled. When several paydays later Thomas and his coworker received salary increases, neither knew whether he had been reclassified as a technician or just given more money because Blalock demanded it.

In the world in which Thomas had grown up, confrontation could be dangerous for a black man. Vivien’s older brother, Harold, had been a school teacher in Nashville. He had sued the Nashville Board of Education, alleging salary discrimination based on race. With the help of an NAACP lawyer named Thurgood Marshall, Harold Thomas had won his suit. But he lost his job. So Vivien had learned the art of avoiding trouble. He recalled: “Had there been an organized complaint by the Negroes performing technical duties, there was a good chance that all kinds of excuses would have been offered to avoid giving us technicians’ pay and that leaders of the movement or action would have been summarily fired.”

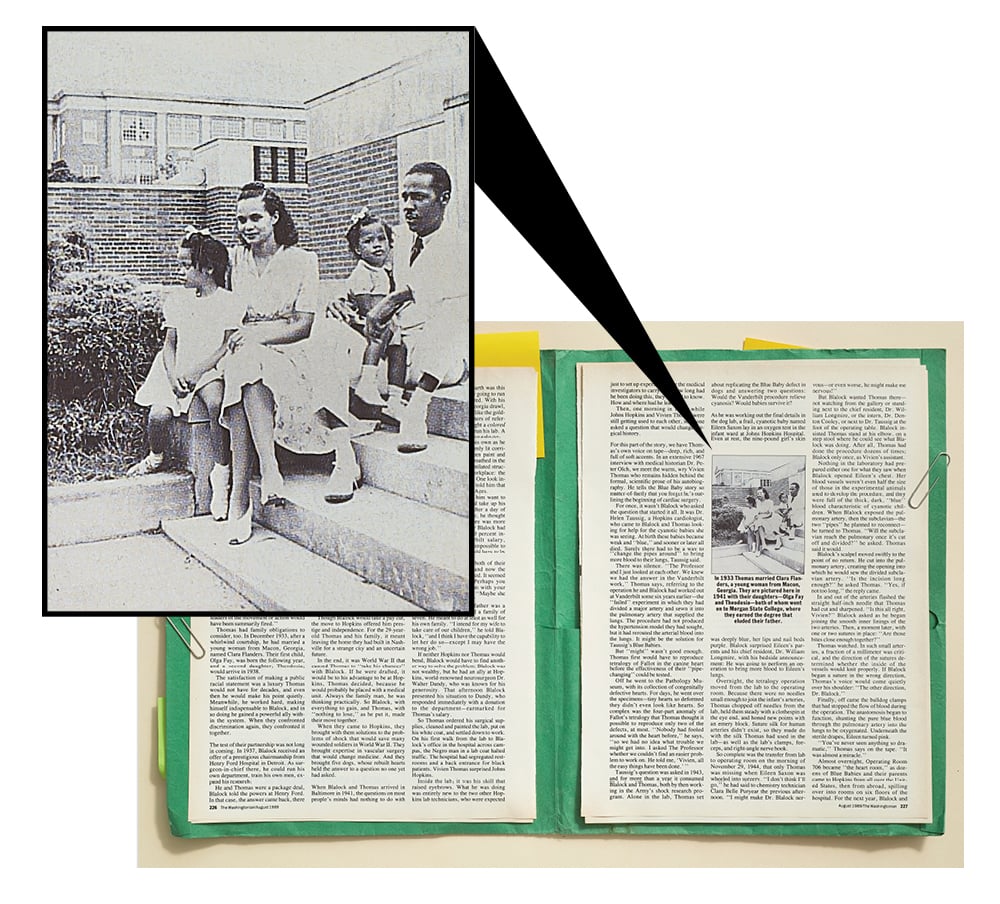

Thomas had family obligations to consider, too. In December 1933, after a whirlwind courtship, he had married a young woman from Macon, Georgia, named Clara Flanders. Their first child, Olga Fay, was born the following year, and a second daughter, Theodosia, would arrive in 1938.

The satisfaction of making a public racial statement was a luxury Thomas would not have for decades, and even then he would make his point quietly. Meanwhile, he worked hard, making himself indispensable to Blalock, and in so doing he gained a powerful ally within the system. When they confronted discrimination again, they confronted it together.

The test of their partnership was not long in coming. In 1937, Blalock received an offer of a prestigious chairmanship from Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. As surgeon-in-chief there, he could run his own department, train his own men, expand his research.

He and Thomas were a package deal, Blalock told the powers at Henry Ford. In that case, the answer came back, there would be no deal. The hospital’s policy against hiring blacks was inflexible. So was his policy on Vivien Thomas, Blalock politely replied.

The two bided their time, teaching themselves vascular surgery in experiments in which they attempted to produce pulmonary hypertension in dogs. The hypertension studies, as such, “were a flop,” Thomas said. But they were one of the most productive flops in medical history.

By 1940, Blalock’s research had put him head and shoulders above any young surgeon in America. When the call came to return to his alma mater, Johns Hopkins, as surgeon-in-chief, he was able to make a deal on his own terms, and it included Thomas. “I want you to go with me to Baltimore,” Blalock told Thomas just before Christmas 1940. Thomas, always his own man, replied, “I will consider it.”

Though Blalock would take a pay cut, the move to Hopkins offered him prestige and independence. For the 29-year-old Thomas and his family, it meant leaving the home they had built in Nashville for a strange city and an uncertain future.

In the end, it was World War II that caused Thomas to “take his chances” with Blalock. If he were drafted, it would be to his advantage to be at Hopkins, Thomas decided, because he would probably be placed with a medical unit. Always the family man, he was thinking practically. So Blalock, with everything to gain, and Thomas, with “nothing to lose,” as he put it, made their move together.

When they came to Hopkins, they brought with them solutions to the problems of shock that would save many wounded soldiers in World War II. They brought expertise in vascular surgery that would change medicine. And they brought five dogs, whose rebuilt hearts held the answer to a question no one yet had asked.

When Blalock and Thomas arrived in Baltimore in 1941, the questions on most people’s minds had nothing to do with cardiac surgery. How on earth was this boyish professor of surgery going to run a department, they wondered. With his simple questions and his Georgia drawl, Blalock didn’t sound much like the golden boy described in his letters of reference. Besides, he had brought a colored man up from Vanderbilt to run his lab. A colored man who wasn’t even a doctor.

Thomas had doubts of his own as he walked down Hopkins’s dimly lit corridors, eyed the peeling green paint and bare concrete floors, and breathed in the odors of the ancient, unventilated structure that was to be his workplace: the Old Hunterian Laboratory. One look inside the instrument cabinet told him that he was in the surgical Dark Ages.

It was enough to make him want to head back to Nashville and take up his carpenter’s tools again.

After a day of house-hunting in Baltimore, he thought he might have to. Baltimore was more expensive than either he or Blalock had imagined. Even with a 20 percent increase over his Vanderbilt salary, Thomas found it “almost impossible to get along.” Something would have to be done, he told Blalock.

Blalock had negotiated both of their salaries from Nashville, and now the deal could not be renegotiated. It seemed that they were stuck. “Perhaps you could discuss the problem with your wife,” Blalock suggested. “Maybe she could get a job to help out.”

Thomas bristled. His father was a builder who had supported a family of seven. He meant to do at least as well for his own family. “I intend for my wife to take care of our children,” he told Blalock, “and I think I have the capability to let her do so—except I may have the wrong job.”

If neither Hopkins nor Thomas would bend, Blalock would have to find another way to solve the problem. Blalock was not wealthy, but he had an ally at Hopkins, world-renowned neurosurgeon Dr. Walter Dandy, who was known for his generosity. That afternoon Blalock presented his situation to Dandy, who responded immediately with a donation to the department—earmarked for Thomas’s salary.

So Thomas ordered his surgical supplies, cleaned and painted the lab, put on his white coat, and settled down to work. On his first walk from the lab to Blalock’s office in the hospital across campus, the Negro man in a lab coat halted traffic. The hospital had segregated restrooms and a back entrance for black patients. Vivien Thomas surprised Johns Hopkins.

Inside the lab, it was his skill that raised eyebrows. What he was doing was entirely new to the two other Hopkins lab technicians, who were expected just to set up experiments for the medical investigators to carry out. How long had he been doing this, they wanted to know. How and where had he learned?

Then, one morning in 1943, while Johns Hopkins and Vivien Thomas were still getting used to each other, someone asked a question that would change surgical history.

For this part of the story, we have Thomas’s own voice on tape—deep, rich, and full of soft accents. In an extensive 1967 interview with medical historian Dr. Peter Olch, we meet the warm, wry Vivien Thomas who remains hidden behind the formal, scientific prose of his autobiography. He tells the Blue Baby story so matter-of-factly that you forget he’s outlining the beginning of cardiac surgery.

For once, it wasn’t Blalock who asked the question that started it all. It was Dr. Helen Taussig, a Hopkins cardiologist, who came to Blalock and Thomas looking for help for the cyanotic babies she was seeing. At birth these babies became weak and “blue,” and sooner or later all died. Surely there had to be a way to “change the pipes around” to bring more blood to their lungs, Taussig said.

There was silence. “The Professor and I just looked at each other. We knew we had the answer in the Vanderbilt work,” Thomas says, referring to the operation he and Blalock had worked out at Vanderbilt some six years earlier—the “failed” experiment in which they had divided a major artery and sewn it into the pulmonary artery that supplied the lungs. The procedure had not produced the hypertension model they had sought, but it had rerouted the arterial blood into the lungs. It might be the solution for Taussig’s Blue Babies.

But “might” wasn’t good enough. Thomas first would have to reproduce tetralogy of Fallot in the canine heart before the effectiveness of their “pipe-changing” could be tested.

Off he went to the Pathology Museum, with its collection of congenitally defective hearts. For days, he went over the specimens—tiny hearts so deformed they didn’t even look like hearts. So complex was the four-part anomaly of Fallot’s tetralogy that Thomas thought it possible to reproduce only two of the defects, at most. “Nobody had fooled around with the heart before,” he says, “so we had no idea what trouble we might get into. I asked The Professor whether we couldn’t find an easier problem to work on. He told me, ‘Vivien, all the easy things have been done.’ ”

Taussig’s question was asked in 1943, and for more than a year it consumed Blalock and Thomas, both by then working in the Army’s shock research program. Alone in the lab, Thomas set about replicating the Blue Baby defect in dogs and answering two questions: Would the Vanderbilt procedure relieve cyanosis? Would babies survive it?

As he was working out the final details in the dog lab, a frail, cyanotic baby named Eileen Saxon lay in an oxygen tent in the infant ward at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Even at rest, the nine-pound girl’s skin was deeply blue, her lips and nail beds purple. Blalock surprised Eileen’s parents and his chief resident, Dr. William Longmire, with his bedside announcement: He was going to perform an operation to bring more blood to Eileen’s lungs.

Overnight, the tetralogy operation moved from the lab to the operating room. Because there were no needles small enough to join the infant’s arteries, Thomas chopped off needles from the lab, held them steady with a clothespin at the eye end, and honed new points with an emery block. Suture silk for human arteries didn’t exist, so they made do with the silk Thomas had used in the lab—as well as the lab’s clamps, forceps, and right-angle nerve hook.

So complete was the transfer from lab to operating room on the morning of November 29, 1944, that only Thomas was missing when Eileen Saxon was wheeled into surgery. “I don’t think I’ll go,” he had said to chemistry technician Clara Belle Puryear the previous afternoon. “I might make Dr. Blalock nervous—or even worse, he might make me nervous!”

But Blalock wanted Thomas there— not watching from the gallery or standing next to the chief resident, Dr. William Longmire, or the intern, Dr. Denton Cooley, or next to Dr. Taussig at the foot of the operating table. Blalock insisted Thomas stand at his elbow, on a step stool where he could see what Blalock was doing. After all, Thomas had done the procedure dozens of times; Blalock only once, as Vivien’s assistant.

He and Thomas were a package deal, Blalock told the hospital. In that case, the answer came back, there would be no deal. Their policy against hiring blacks was inflexible.

Nothing in the laboratory had prepared either one for what they saw when Blalock opened Eileen’s chest. Her blood vessels weren’t even half the size of those in the experimental animals used to develop the procedure, and they were full of the thick, dark, “blue” blood characteristic of cyanotic children. When Blalock exposed the pulmonary artery, then the subclavian—the two “pipes” he planned to reconnect— he turned to Thomas. “Will the subclavian reach the pulmonary once it’s cut off and divided?” he asked. Thomas said it would.

Blalock’s scalpel moved swiftly to the point of no return. He cut into the pulmonary artery, creating the opening into which he would sew the divided subclavian artery. “Is the incision long enough?” he asked Thomas. “Yes, if not too long,” the reply came.

In and out of the arteries flashed the straight half-inch needle that Thomas had cut and sharpened. “Is this all right, Vivien?” Blalock asked as he began joining the smooth inner linings of the two arteries. Then, a moment later, with one or two sutures in place: “Are those bites close enough together?”

Thomas watched. In such small arteries, a fraction of a millimeter was critical, and the direction of the sutures determined whether the inside of the vessels would knit properly. If Blalock began a suture in the wrong direction, Thomas’s voice would come quietly over his shoulder: “The other direction. Dr. Blalock.”

Finally, off came the bulldog clamps that had stopped the flow of blood during the operation. The anastomosis began to function, shunting the pure blue blood through the pulmonary artery into the lungs to be oxygenated. Underneath the sterile drapes, Eileen turned pink.

“You’ve never seen anything so dramatic,” Thomas says on the tape. “It was almost a miracle.”

Almost overnight, Operating Room 706 became “the heart room,” as dozens of Blue Babies and their parents came to Hopkins from all over the United States, then from abroad, spilling over into rooms on six floors of the hospital. For the next year, Blalock and Longmire rebuilt hearts virtually around the clock. One after another, cyanotic children who had never been able to sit upright began standing at their crib rails, pink and healthy.

It was the beginning of modern cardiac surgery, but to Thomas it looked like chaos. Blue Babies arrived daily, yet Hopkins had no cardiac ward, no catheterization lab, no sophisticated apparatus for blood studies. They had only Vivien Thomas, who flew from one end of the Hopkins complex to the other without appearing to hurry.

From his spot at Blalock’s shoulder in the operating room, Thomas would race to the wards, where he would take arterial blood samples on the Blue Babies scheduled for surgery, hand off the samples to another technician in the hallway, return to the heart room for the next operation, head for the lab to begin the blood-oxygen studies, then go back to his spot in the OR.

“Only Vivien is to stand there,” Blalock would tell anyone who moved into the space behind his right shoulder.

Each morning at 7:30, the great screened windows of Room 706 would be thrown open, the electric fan trained on Dr. Blalock, and the four-inch beam of the portable spotlight focused on the operating field. At the slightest movement of light or fan, Blalock would yell at top voice, at which point his orderly would readjust both.

Then the perspiring Professor would complete the procedure, venting his tension with a whine so distinctive that a generation of surgeons still imitate it. “Must I operate all alone? Won’t somebody please help me?” he’d ask plaintively, stomping his soft white tennis shoes and looking around at the team standing ready to execute his every order. And lest Thomas look away, Blalock would plead over his shoulder, “Now you watch, Vivien, and don’t let me put these sutures in wrong!”

Visitors had never seen anything like it. More than Blalock’s whine, it was Thomas’s presence that mystified the distinguished surgeons who came from all over the world to witness the operation. They could see that the black man on the stool behind Dr. Blalock was not an MD. He was not scrubbed in as an assistant, and he never touched the patients. Why did the famous doctor keep turning to him for advice?

If outsiders puzzled at Thomas’s role, the surgical team took it as a matter of course. “Who else but Vivien could have answered those technical questions?” asks Dr. William Longmire, now professor emeritus at UCLA’s School of Medicine. “Dr. Blalock was plowing new ground beyond the horizons we’d ever seen before. Nobody knew how to do this.”

“It was a question of trust,” says Dr. Alex Haller, who was trained by Thomas and now is surgeon-in-chief at Hopkins. Sooner or later, he says, all the stories circle back to that moment when Thomas and Blalock stood together in the operating room for the first Blue Baby. Had Blalock not believed in Thomas’s lab results with the tetralogy operation, he would never have dared to open Eileen Saxon’s chest.

“Once Dr. Blalock accepted you as a colleague, he trusted you completely—I mean, with his life.” Haller says. After his patients, nothing mattered more to Blalock than his research and his “boys,” as he called his residents. To Thomas he entrusted both and, in so doing, doubled his legacy.

“Dr. Blalock let us know in no uncertain terms, ‘When Vivien speaks, he’s speaking for me,’ ” remembers Dr. David Sabiston, who left Hopkins in 1964 to chair Duke University’s department of surgery. We revered him as we did our professor.”

To Blalock’s “boys,” Thomas became the model of a surgeon. “Dr. Blalock was a great scientist, a great thinker, a leader,” explains Denton Cooley, “but by no stretch of the imagination could he be considered a great cutting surgeon. Vivien was.”

What passed from Thomas’s hands to the surgical residents who would come to be known as “the Old Hands” was vascular surgery in the making—much of it of Thomas’s making. He translated Blalock’s concepts into reality, devising techniques, even entire operations, where none had existed.

In any other hospital, Thomas’s functions as research consultant and surgical instruction might have been filled by as many as four specialists. Yet Thomas was always the patient teacher. And he never lost his sense of humor.

“I remember one time,” says Haller, “when I was a medical student, I was working on a research project with a senior surgical resident who was a very slow operator. The procedure we were doing would ordinarily have taken an hour, but it had taken us six or seven hours, on this one dog that had been asleep all that time. There I was, in one position for hours, and I was about to die.

“Well, finally, the resident realized that the dog hadn’t had any fluids intravenously, so he called over to Vivien, ‘Vivien, would you come over and administer some I-V fluids?’ Now, the whole time Vivien had been watching us out of the corner of his eye from across the lab, not saying a word, but not missing a thing, either. I must have looked white as a ghost, because when he came over with the I-V needle, he sat down at my foot, tugged at my pants leg, and said, ‘Which leg shall I start the fluid in, Dr. Haller?’ ”

The man who tugged at Haller’s pants leg administered one of the country’s most sophisticated surgical research programs. “He was strictly no-nonsense about the way he ran that lab,” Haller says. “Those dogs were treated like human patients.”

One of the experimental animals, Anna, took on legendary status as the first long-term survivor of the Blue Baby operation, taking up permanent residence in the Old Hunterian as Thomas’s pet. It was during “Anna’s era,” Haller says, that Thomas became surgeon-in-residence to the pets of Hopkins’s faculty and staff. On Friday afternoons, Thomas opened the Old Hunterian to the pet owners of Baltimore and presided over an afternoon clinic, gaining as much prestige in the veterinary community as he enjoyed within the medical school. “Vivien knew all the senior vets in Baltimore,” Haller explains, “and if they had a complicated surgical problem, they’d call on Vivien for advice, or simply ask him to operate on their animals.”

By the late 1940s, the Old Hunterian had become “Vivien’s domain,” says Haller. “There was no doubt in anybody’s mind as to who was in charge. Technically, a non-MD could not hold the position of laboratory supervisor. Dr. Blalock always had someone on the surgical staff nominally in charge, but it was Vivien who actually ran the place.”

As quietly as he had come through Hopkins’s door at Blalock’s side, Thomas began bringing in other black men, moving them into the role he had first carved out for himself. To the black technicians he trained—twenty of them over three decades—he was “Mr. Thomas,” a man who represented what they themselves might become. Two of the twenty went on to medical school, but most were men like Thomas, with only high school diplomas and no prospect of further education. Thomas trained them and sent them out with the Old Hands, who tried to duplicate the Blalock-Thomas magic in their own labs.

Perhaps none bears Thomas’s imprint more than Raymond Lee, a former elevator operator who became the first non-MD to serve on Hopkins’s cardiac surgical service as a physician’s assistant. For the Hopkins cardiac team headed by Drs. Vincent Gott and Bruce Reitz, 1987 was a year of firsts, and Lee was part of both: In May, he assisted in a double heart-lung transplant, the first from a living donor; in August, he was a member of the Hopkins team that successfully separated Siamese twins.

Raymond Lee hasn’t come into the hospital on his day off to talk about his role in those historic 1987 operations. He has come “to talk about Mr. Thomas,” and as he does so, you begin to see why Alex Haller has described Lee as “another Vivien.” Lee speaks so softly you have to strain to hear him above the din of the admitting room. “It’s been almost 25 years,” he says, “since Mr. Thomas got a hold of me in the elevator of the Halsted Building and asked me if I might be interested in becoming a laboratory assistant.”

Along with surgical technique, Thomas imparted to his technicians his own philosophy. “Mr. Thomas would always tell us, ‘Everybody’s got a job to do. You are put here to do a job 100 percent, regardless of how much education you have.’ He believed that if you met the right people at the right time, and you can prove yourself, then you can achieve what you were meant to do.”

Alex Haller tells of another Thomas technician, a softspoken man named Alfred Casper: “After I’d completed my internship at Hopkins, I went to work in the lab at NIH. I was the only one in the lab, except for Casper. He had spent some time observing Vivien and working with him. We were operating together on one occasion, and we got into trouble with some massive bleeding in a pulmonary artery, which I was able to handle fairly well. Casper said to me, ‘Dr. Haller, I was very much impressed with the way you handled yourself there.’ Feeling overly proud of myself, I said to Casper, ‘Well, I trained with Dr. Blalock.’

“A few weeks later, we were operating together in the lab for a second time, and we got into even worse trouble. I literally did not know what to do. Casper immediately took over, placed the clamps appropriately, and got us out of trouble. I turned to him at the end of it and said, ‘I certainly appreciated the way you solved that problem. You handled your hands beautifully, too.’

“He looked me in the eye and said, ‘I trained with Vivien.’ ”

Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas: Their names intertwine, their partnership overshadowing the individual legacies they handed down to dozens of Hallers and Caspers. For more than three decades, the partnership endured, as Blalock ascended to fame, built up young men in his own image, then became a proud but reluctant bystander as they rose to dominate the field he had created.

As close as Blalock was to his protégés, they moved on. It was Thomas who remained, the one constant. From the first, Thomas had seen the worst and the best of Blalock. Thomas knew the famous Blue Baby doctor the world could not see: a profoundly conscientious surgeon, devastated by patient mortality and keenly aware of his own limitations.

In 1950, six years after he and Blalock had stood together for Blue Baby One, Blalock operated on Blue Baby 1,000. It was a triumphant moment—an occasion that called for a Yousuf Karsh portrait, a surprise party at the Blalock home, gifts of Scotch and bourbon, and a long evening of reminiscing with the Old Hands. Thomas almost wasn’t there.

As Blalock was laying plans for his 1947 “Blue Baby Tour” of Europe, Thomas was preparing to head back home to Nashville, for good. The problem was money. There was no provision in Hopkins’s salary classification for an anomaly like Thomas: a non-degreed technician with the responsibilities of a postdoctoral research fellow.

With no regret for the past, the 35-year-old Thomas took a hard look at the future and at his two daughters’ prospects for earning the degrees that had eluded him. Weighing the Hopkins pay scale against the postwar building boom in Nashville, he decided to head south to build houses.

“It’s a chance I have to take,” he told Blalock. “I don’t know what will happen if I leave Hopkins, but I know what will happen if I stay. ”He made no salary demands, but simply announced his intention to leave, assuming that Blalock would be powerless against the system.

Two days before Christmas 1946, Blalock came to Thomas in the empty lab with Hopkins’s final salary offer, negotiated by Blalock and approved by the board of trustees that morning. “I hope you will accept this,” he told Thomas, drawing a file card from his pocket. “It’s the best I can do—it’s all I can do.”

The offer on the card left Thomas speechless: The trustees had doubled his salary and created a new bracket for non-degreed personnel deserving higher pay. From that moment, money ceased to be an issue.

Until Blalock’s retirement in 1964, the two men continued their partnership. The harmony between the idea man and the detail man never faltered. Blalock took care of patients, Thomas took care of research. Only their rhythm changed.

In the hectic Blue Baby years, Blalock would leave his hospital responsibilities at the door of the Old Hunterian at noon and closet himself with Thomas for a five-minute research update. In the evenings, with Thomas’s notes at one elbow and a glass of bourbon at the other, Blalock would phone Thomas from his study as he worked on scientific papers late into the night. “Vivien, I want you to listen to this,” he’d say before reading two or three sentences from the pad in his lap, asking, “Is that your impression?” or “Is it all right if I say so-and-so?”

As the hectic pace of the late ’40s slowed in the early ’50s, the hurried noon visits and evening phone conversations gave way to long, relaxed exchanges through the open door between lab and office.

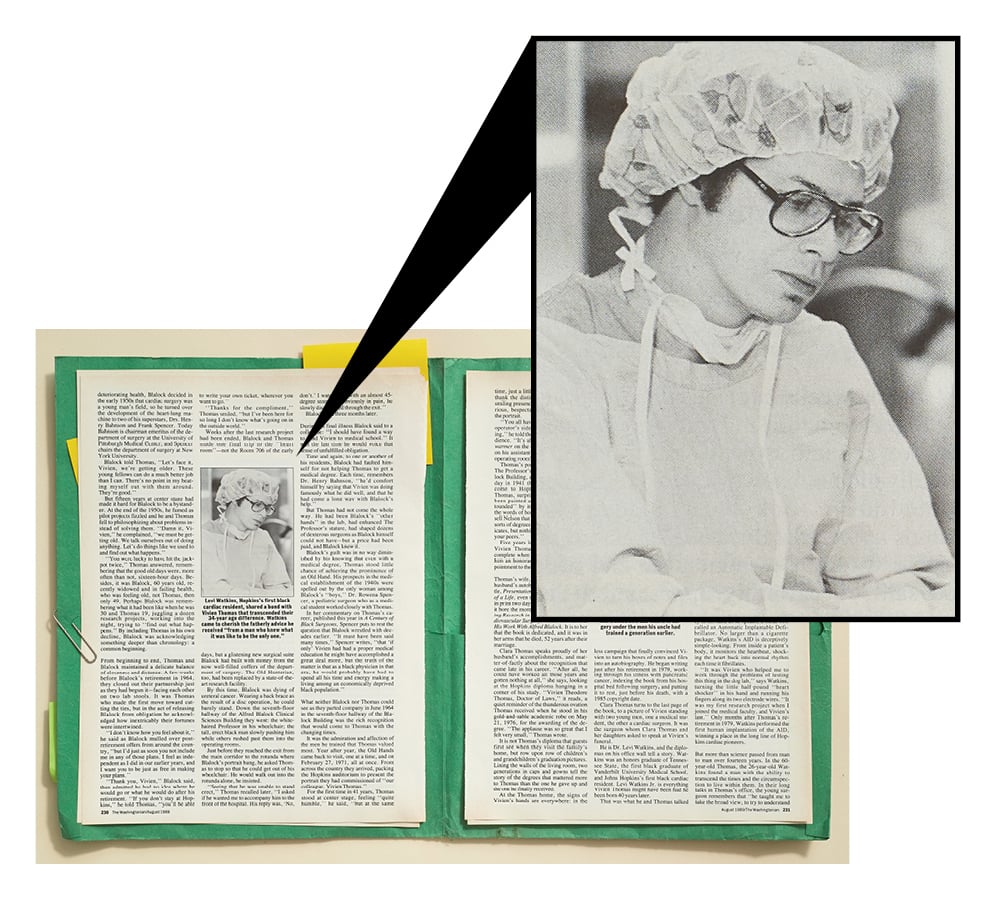

Along the way, Thomas and Blalock grew old together, Thomas gracefully, Blalock more reluctantly. Sidelined by deteriorating health, Blalock decided in the early 1950s that cardiac surgery was a young man’s field, so he turned over the development of the heart-lung machine to two of his superstars, Drs. Henry Bahnson and Frank Spencer. Today Bahnson is chairman emeritus of the department of surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and Spencer chairs the department of surgery at New York University.

Blalock told Thomas, “Let’s face it, Vivien, we’re getting older. These young fellows can do a much better job than I can. There’s no point in my beating myself out with them around. They’re good.”

But fifteen years at center stage had made it hard for Blalock to be a bystander. At the end of the 1950s, he fumed as pilot projects fizzled and he and Thomas fell to philosophizing about problems instead of solving them. “Damn it, Vivien,” he complained, “we must be getting old. We talk ourselves out of doing anything. Let’s do things like we used to and find out what happens.”

“You were lucky to have hit the jackpot twice,” Thomas answered, remembering that the good old days were, more often than not, sixteen-hour days. Besides, it was Blalock, 60 years old, recently widowed and in failing health, who was feeling old, not Thomas, then only 49. Perhaps Blalock was remembering what it had been like when he was 30 and Thomas 19, juggling a dozen research projects, working into the night, trying to “find out what happens.” By including Thomas in his own decline, Blalock was acknowledging something deeper than chronology: a common beginning.

From beginning to end, Thomas and Blalock maintained a delicate balance of closeness and distance. A few weeks before Blalock’s retirement in 1964, they closed out their partnership just as they had begun it—facing each other on two lab stools. It was Thomas who made the first move toward cutting the ties, but in the act of releasing Blalock from obligation he acknowledged how inextricably their fortunes were intertwined.

“I don’t know how you feel about it,” he said as Blalock mulled over post-retirement offers from around the country, “but I’d just as soon you not include me in any of those plans. I feel as independent as I did in our earlier years, and I want you to be just as free in making your plans.”

“Thank you, Vivien,” Blalock said, then admitted he had no idea where he would go or what he would do after his retirement. “If you don’t stay at Hopkins,” he told Thomas, “you’ll be able to write your own ticket, wherever you want to go.”

“Thanks for the compliment,” Thomas smiled, “but I’ve been here for so long I don’t know what’s going on in the outside world.”

Weeks after the last research project had been ended, Blalock and Thomas made one final trip to the “heart room”—not the Room 706 of the early days, but a glistening new surgical suite Blalock had built with money from the now well-filled coffers of the department of surgery. The Old Hunterian, too, had been replaced by a state-of-the-art research facility.

“I turned to him and said, ‘I certainly appreciated the way you solved that problem. You handled your hands beautifully.’ He looked me in the eye and said, ‘I trained with Vivien.'”

By this time, Blalock was dying of ureteral cancer. Wearing a back brace as the result of a disc operation, he could barely stand. Down the seventh-floor hallway of the Alfred Blalock Clinical Sciences Building they went: the white-haired Professor in his wheelchair; the tall, erect black man slowly pushing him while others rushed past them into the operating rooms.

Just before they reached the exit from the main corridor to the rotunda where Blalock’s portrait hung, he asked Thomas to stop so that he could get out of his wheelchair. He would walk out into the rotunda alone, he insisted.

“Seeing that he was unable to stand erect,” Thomas recalled later, “I asked if he wanted me to accompany him to the front of the hospital. His reply was, ‘No, don’t.’ I watched as with an almost 45-degree stoop and obviously in pain, he slowly disappeared through the exit.”

Blalock died three months later.

During his final illness Blalock said to a colleague: “I should have found a way to send Vivien to medical school.” It was the last time he would voice that sense of unfulfilled obligation.

Time and again, to one or another of his residents, Blalock had faulted himself for not helping Thomas to get a medical degree. Each time, remembers Dr. Henry Bahnson, “he’d comfort himself by saying that Vivien was doing famously what he did well, and that he had come a long way with Blalock’s help.”

But Thomas had not come the whole way. He had been Blalock’s “other hands” in the lab, had enhanced The Professor’s stature, had shaped dozens of dexterous surgeons as Blalock himself could not have—but a price had been paid, and Blalock knew it.

Blalock’s guilt was in no way diminished by his knowing that even with a medical degree, Thomas stood little chance of achieving the prominence of an Old Hand. His prospects in the medical establishment of the 1940s were spelled out by the only woman among Blalock’s “boys,” Dr. Rowena Spencer, a pediatric surgeon who as a medical student worked closely with Thomas.

In her commentary on Thomas’s career, published this year in A Century of Black Surgeons, Spencer puts to rest the question that Blalock wrestled with decades earlier. “It must have been said many times,” Spencer writes, “that ‘if only’ Vivien had had a proper medical education he might have accomplished a great deal more, but the truth of the matter is that as a black physician in that era, he would probably have had to spend all his time and energy making a living among an economically deprived black population.”

What neither Blalock nor Thomas could see as they parted company in June 1964 in the seventh-floor hallway of the Blalock Building was the rich recognition that would come to Thomas with the changing times.

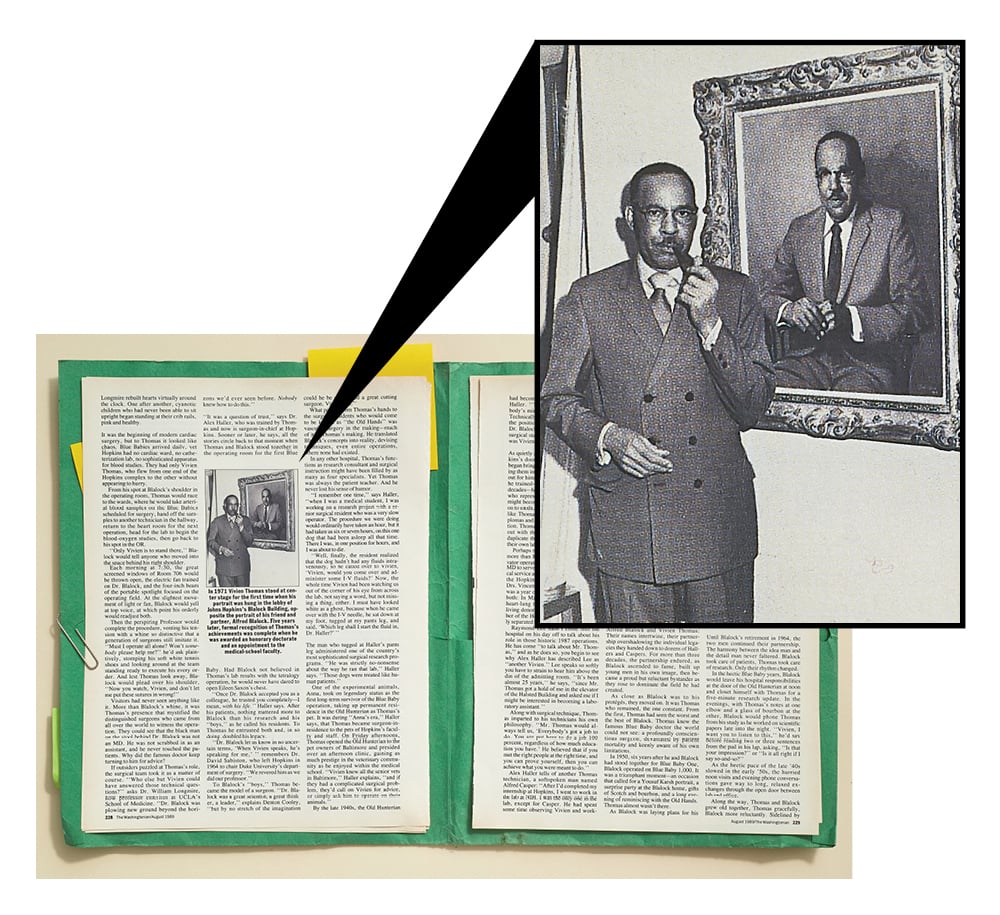

It was the admiration and affection of the men he trained that Thomas valued most. Year after year, the Old Hands came back to visit, one at a time, and on February 27, 1971, all at once. From across the country they arrived, packing the Hopkins auditorium to present the portrait they had commissioned of “our colleague, Vivien Thomas.”

For the first time in 41 years, Thomas stood at center stage, feeling “quite humble,” he said, “but at the same time, just a little bit proud.” He rose to thank the distinguished gathering, his smiling presence contrasting with the serious, bespectacled Vivien Thomas in the portrait.

‘‘You all have got me working on the operator’s side of the table this morning,” he told the standing-room-only audience. “It’s always just a few degrees warmer on the operator’s side than it is on his assistant’s when you get into the operating room!”

Thomas’s portrait was hung opposite The Professor’s in the lobby of the Blalock Building, almost 30 years from the day in 1941 that he and Blalock had come to Hopkins from Vanderbilt. Thomas, surprised that his portrait had been painted at all, said he was “astounded” by its placement. But it was the words of hospital president Dr. Russell Nelson that hit home: “There are all sorts of degrees and diplomas and certificates, but nothing equals recognition by your peers.”

Five years later, the recognition of Vivien Thomas’s achievements was complete when Johns Hopkins awarded him an honorary doctorate and an appointment to the medical-school faculty.

Thomas’s wife, Clara, still refers to her husband’s autobiography by Vivien’s title, Presentation of a Portrait: The Story of a Life, even though when it appeared in print two days after his death in 1985, it bore the more formal title of Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery: Vivien Thomas and His Work With Alfred Blalock. It is to her that the book is dedicated, and it was in her arms that he died, 52 years after their marriage.

Clara Thomas speaks proudly of her husband’s accomplishments, and matter-of-factly about the recognition that came late in his career. “After all, he could have worked all those years and gotten nothing at all,” she says, looking at the Hopkins diploma hanging in a corner of his study. “Vivien Theodore Thomas, Doctor of Laws,” it reads, a quiet reminder of the thunderous ovation Thomas received when he stood in his gold-and-sable academic robe on May 21, 1976, for the awarding of the degree. “The applause was so great that I felt very small,” Thomas wrote.

It is not Thomas’s diploma that guests first see when they visit the family’s home, but row upon row of children’s and grandchildren’s graduation pictures. Lining the walls of the living room, two generations in caps and gowns tell the story of the degrees that mattered more to Thomas than the one he gave up and the one he finally received.

At the Thomas home, the signs of Vivien’s hands are everywhere: in the backyard rose garden, the mahogany mantelpiece he made from an old piano top, the Victorian sofa he upholstered, the quilt his mother made from a design he had drawn when he was nine years old.

The book was the last work of Vivien Thomas’s life, and probably the most difficult. It was the Old Hands’ relentless campaign that finally convinced Vivien to turn his boxes of notes and files into an autobiography. He began writing just after his retirement in 1979, working through his illness with pancreatic cancer, indexing the book from his hospital bed following surgery, and putting it to rest, just before his death, with a 1985 copyright date.

Clara Thomas turns to the last page of the book, to a picture of Vivien standing with two young men, one a medical student, the other a cardiac surgeon. It was the surgeon whom Clara Thomas and her daughters asked to speak at Vivien’s funeral.

He is Dr. Levi Watkins, and the diplomas on his office wall tell a story. Watkins was an honors graduate of Tennessee State, the first black graduate of Vanderbilt University Medical School, and Johns Hopkins’s first black cardiac resident. Levi Watkins Jr. is everything Vivien Thomas might have been had he been born 40 years later.

That was what he and Thomas talked about the day they met in the hospital cafeteria, a few weeks after Watkins had come to Hopkins as an intern in 1971. “You’re the man in the picture,” he had said. And Thomas had smiled and invited him up to his office.

“He was so modest that I had to keep asking him, ‘What did you do to get your picture on the wall?’ ” says Watkins of his first meeting with a man who was for fourteen years “a colleague, a counselor, a friend.”

“Even though I only knew him a fraction of the time some of the other surgeons did, I felt very close to him. From the very beginning, there was this deeper bond between us: I knew that he had been where I had been, and I had been where he could not go.”

Both men were aware that their differences ran deep: Watkins, whose exposure to the early civil-rights movement as a parishioner of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. had taught him to be “out front and vocal about minority participation”; and Thomas, whose upbringing in Louisiana and Tennessee in the early years of the century had taught him the opposite. “I think Vivien admired what I did,” says Watkins, “but he knew that we were different. There was a generation’s difference between Vivien and me, and it was a big generation. Survival was a much stronger element in his background. Vivien was a trailblazer by his work.”

Watkins holds part of Thomas’s legacy in his hand as he speaks, a metal box called an Automatic Implantable Defibrillator. No larger than a cigarette package, Watkins’s AID is deceptively simple-looking. From inside a patient’s body, it monitors the heartbeat, shocking the heart back into normal rhythm each time it fibrillates.

“It was Vivien who helped me to work through the problems of testing this thing in the dog lab,” says Watkins, turning the little half-pound “heart shocker” in his hand and running his fingers along its two electrode wires. “It was my first research project when I joined the medical faculty, and Vivien’s last.” Only months after Thomas’s retirement in 1979, Watkins performed the first human implantation of the AID, winning a place in the long line of Hopkins cardiac pioneers.

But more than science passed from man to man over fourteen years. In the 60-year-old Thomas, the 26-year-old Watkins found a man with the ability to transcend the times and the circumspection to live within them. In their long talks in Thomas’s office, the young surgeon remembers that “he taught me to take the broad view, to try to understand Hopkins and its perspective on race. He talked about how powerful Hopkins was, how traditional. He was concerned with my being too political and antagonizing the people I had to work with. He would check on me from time to time, just to make sure everything was all right. He worried about my getting out there alone.”

It was ‘‘fatherly advice,” Watkins says fondly, “from a man who knew what it was like to be the only one.” When Thomas retired, one era ended and another began, for that was the year that Levi Watkins joined the medical-school admissions committee. Within four years, minority enrollment quadrupled. “When Vivien saw the number of black medical students increasing so dramatically, he was happy—he was happy,” says Watkins.

Always one for gentle statements, Thomas celebrated the changing times on the last page of his book: Thomas is shown standing proudly next to Levi Watkins and a third-year medical student named Reginald Davis, who is holding his infant son. According to the caption, the photograph was taken in 1979 in front of the hospital’s Broadway entrance. But the true message lies in what the caption does not say: In 1941, the Broadway entrance was for whites only.

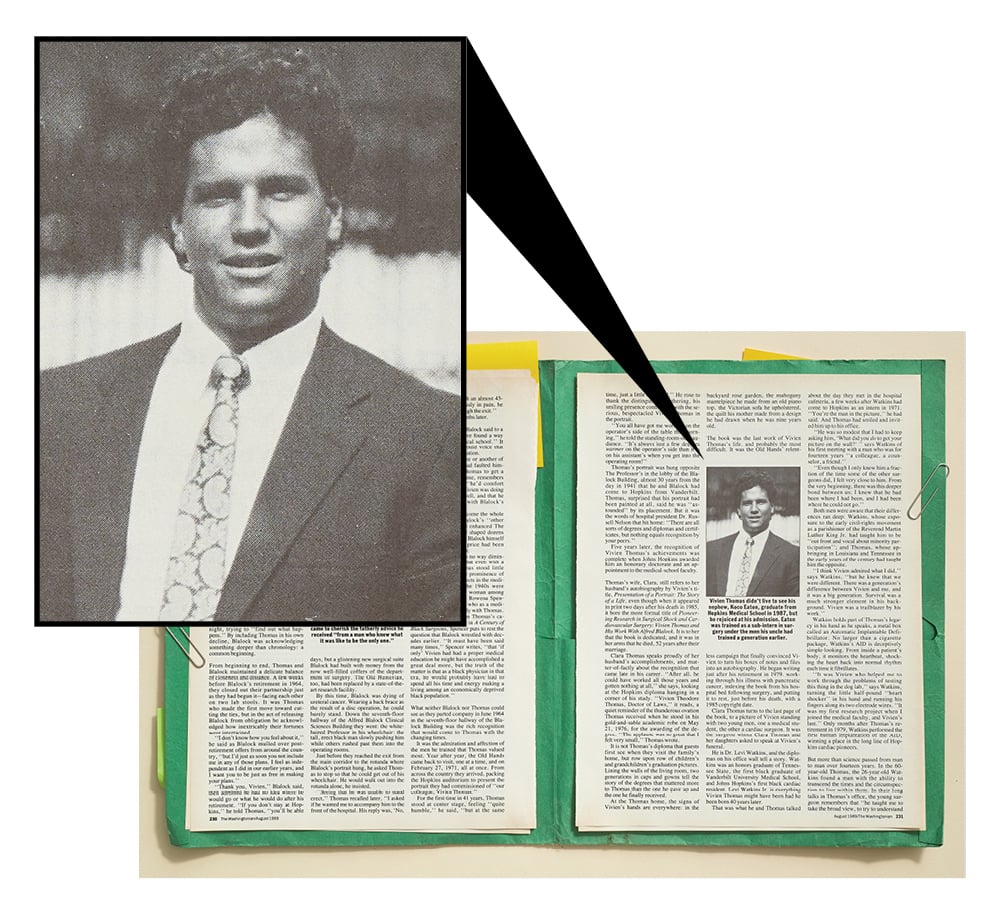

Had the photograph been taken eight years later, it might have included Thomas’s nephew, Koco Eaton, a 1987 graduate of the Johns Hopkins Medical School, trained as a sub-intern in surgery by the men his uncle had trained a generation earlier. Thomas did not live to see his nephew graduate, but he rejoiced at his admission. “I remember Vivien coming to me in my office,” says Watkins, “and telling me how much it meant to him to have all the doors open for Koco that had been closed to him.”

Up and down the halls of Hopkins, Koco Eaton turned heads—not because he was black, but because he was the nephew of Vivien Thomas.

It was on a summer afternoon in 1928 that Vivien Thomas says he learned the standard of perfection that won him so much esteem. He was just out of high school, working on the Fisk University maintenance crew to earn money for his college tuition. He had spent all morning fixing a piece of worn flooring in one of the faculty houses. Shortly after noon, the foreman came by to inspect.

“He took one look,” Thomas remembered, and said, ‘Thomas, that won’t do. I can tell you put it in.’ Without another word, he turned and left. I was stung, but I replaced the piece of flooring. This time I could barely discern which piece I had put in. . . . Several days later the foreman said to me, ‘Thomas, you could have fixed that floor right in the first place.’ I knew that I had already learned the lesson which I still remember and try to adhere to: Whatever you do, always do your best. . . . I never had to repeat or redo another assignment.”

So it went for more than half a century. “The Master,” Rollins Hanlon called him the day he presented Thomas’s portrait on behalf of the Old Hands. Hanlon, the surgeon and scholar, spoke of Thomas’s hands, and of the man who was greater still; of the synergy of two great men, Thomas and Blalock.

Today, in heavy gilt frames, those two men silently look at each other from opposite walls of the Blalock Building, just as one morning 40 years ago they stood in silence at Hopkins. Thomas had surprised The Professor with an operation he had conceived, then kept secret until healing was completed. The first and only one conceived entirely by Thomas, it was a complex but now common operation called an atrial septectomy.

“The foreman said, ‘Thomas, you could have fixed that floor right in the first place.’ I knew that I had learned the lesson I still try to adhere to: Whatever you do, always do your best.”

Using a canine model, he had found a way to improve circulation in patients whose great vessels were transposed. The problem had stymied Blalock for months, and now it seemed that Thomas had solved it.

“Neither he nor I spoke for some four or five minutes while he stood there examining the heart, running the tip of his finger back and forth through the moderate-size defect in the atrial septum, feeling the healed edges of the defect. . . . We examined the outside of the heart and found the suture line with most of the silk still intact. This was the only evidence that an incision had been made in the heart.

“Internal healing of the incision was without flaw. The sutures could not be seen from within, and on gross examination the edges of the defect were smooth and covered with endocardium. Dr. Blalock finally broke the silence by asking, ‘Vivien, are you sure you did this?’ I answered in the affirmative, and then after a pause he said, ‘Well, this looks like something the Lord made.’ ”

A reprinted version of this August 1989 article appears in the May 2020 issue of Washingtonian.