It was around 2:30 AM—a couple hours before closing time at the strip club—when Cesar Sayoc’s coworkers noticed him acting strangely. A bouncer and occasional emcee at the club, Sayoc had worked that night but finished up earlier. Now he’d come back in, taken a seat at a table, and, using the glow from his cell phone, begun leafing through two black binders.

The staff at the Ultra Gentlemen’s Club, just around the corner from the Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach, Florida, had gotten used to Sayoc hanging around when he was off the clock. But his focus on the documents was odd. Curious, a coworker walked over to Sayoc’s table for a peek and saw something disturbing. Inside one of the binders were hundreds of pictures of people’s faces—media clippings that appeared to have been cut out and arranged into a collage. The kind of thing, the coworker later explained to the FBI, “that you see out of a movie that a serial killer would use.”

A short while later, another bizarre incident took place. The coworker walked out of the club and, while outside, heard someone yell, “Fire!” He then saw Sayoc in the parking lot, standing next to an open flame. Although Sayoc explained that he was just burning old bills, the two episodes made the coworker uneasy. He went upstairs and told the night manager about Sayoc’s behavior. At one point, the coworker joked, “What is this guy, the bomber?”

Both men chuckled.

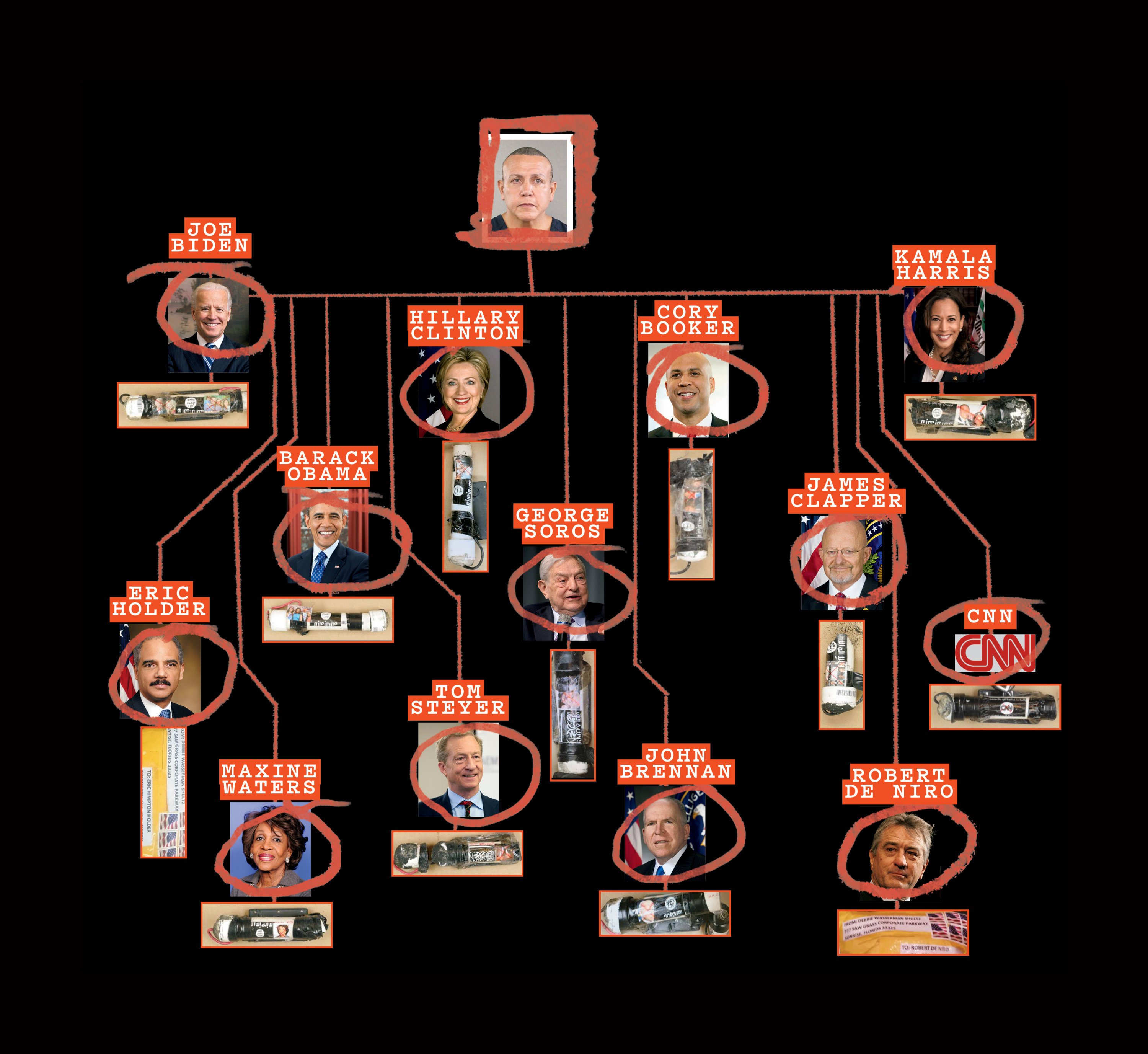

It was October 26, 2018, less than two weeks before that year’s midterm elections—when Democrats hoped to take back the House—and the country was in the grip of a surreal and terrifying mystery. Four days earlier, a mail bomb had been discovered at the suburban New York home of billionaire and liberal activist George Soros. The following day, a similar package was delivered to Hillary Clinton’s residence in Chappaqua, New York. Twenty-four hours later, Barack Obama received one at a PO box his family uses in Washington. By the time it was over, 12 high-profile critics of Donald Trump—including Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Robert De Niro—would be targeted, along with a news network. Each package contained an envelope of powder designed to look like anthrax. And affixed to the bombs was an image of a black flag like those used by ISIS, as well as a picture of the intended victim with a red X marked across his or her face.

The explosives had an amateurish quality. The perpetrator sometimes misspelled his intended recipients’ names—writing “Maxim Waters,” for instance, for California congresswoman and frequent Trump Twitter target Maxine Waters. And although the handmade pipe bombs were packed with fertilizer, explosive powder from fireworks, and glass shards, they weren’t assembled properly, so none actually detonated. Still, the near daily mail-bomb attacks on some of America’s most powerful figures dominated the news cycle. CNN anchors Poppy Harlow and Jim Sciutto were discussing the incidents on air when an explosive device was discovered in the very New York offices they were broadcasting from. They fled the building and continued reporting live from the sidewalk.

With the election approaching, authorities mobilized a massive effort to identify and locate the mastermind of the plot—the so-called MAGA bomber. The FBI’s New York Joint Terrorism Task Force led a team of 50 different law-enforcement agencies in a nationwide manhunt, investigating more than a thousand leads and tips. Each day that they failed to apprehend the perpetrator, additional explosives were discovered and the threat escalated.

At the strip club down the street from Trump’s golf course, Sayoc’s coworker returned downstairs and found Sayoc seated at a table again. The television was tuned to a news station. When a segment came on about the bombs, the coworker erupted. “Who would do this?” he asked. “They should kill him, that son of a bitch.” Sayoc remained quiet. He just stared at the TV, nodding his head in silence.

Eventually, the few remaining employees left the club and locked the doors for the night. As Sayoc walked toward his van, he called back to his coworkers.

“Love you guys!” he said.

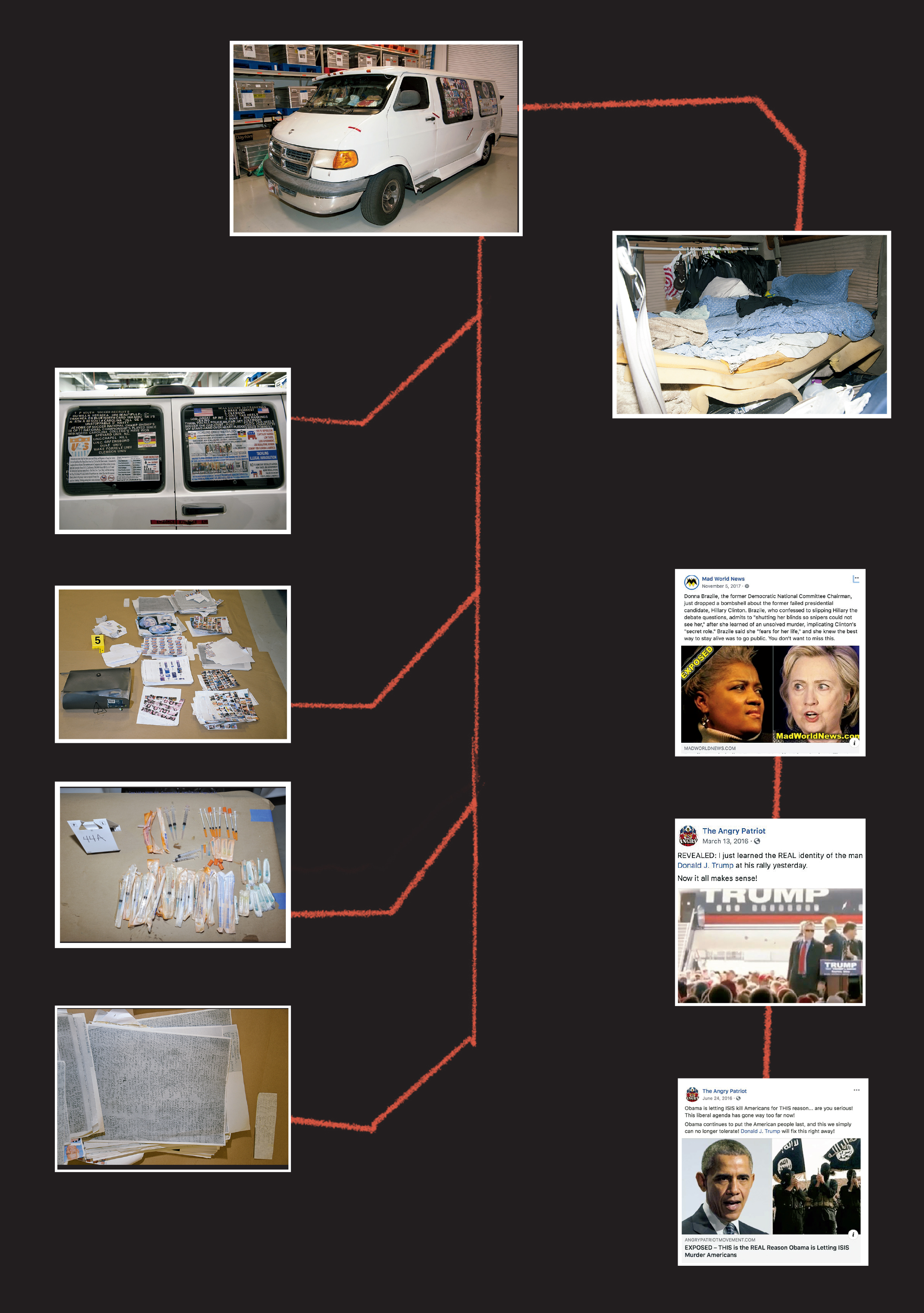

A few hours later, 50 officers with their guns drawn ambushed Sayoc outside an AutoZone store. His coworker’s uneasy feelings—about the weird binders, the unexplained fire in the parking lot—no longer amounted to run-of-the-mill jokes about that creepy guy from work. Investigators discovered that Sayoc’s van, which doubled as his home, was plastered with pro-Trump posters. Inside, they found evidence of an unhinged man with a political obsession: a Trump-Pence T-shirt pulled over the passenger seat, headshots of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton tossed among the clutter, and page after page of chilling writings, including “Kill your enemy.”

Cesar Sayoc was indeed the MAGA bomber, and his campaign of terror had come to an end. He went on to plead guilty to 65 felonies—including 16 counts of using a weapon of mass destruction.

During the court proceedings, his attorneys made clear what had been apparent from the start: Sayoc’s actions were motivated by his support for the President. This admission, though, sparked a new mystery. Out of the tens of millions of Trump die-hards, only Sayoc, as far as anyone knows, had turned that MAGA energy into serial attacks against sitting lawmakers, former government officials, and an out-of-favor TV network. What had pushed him over the edge?

“The first thing you hear entering [a] Trump rally is we are not going to take it anymore, the forgotten ones, etc. It was fun. It became like a new found drug.”

The answer, according to previously unpublished documents and interviews with those who knew Sayoc, involves a story of mental illness and childhood trauma. But it also involves a radicalization in the fever swamps of right-wing online conspiracy theories and cable-TV hosts. Most important, it involves a devotion to Donald J. Trump that began well before the 45th President entered politics, when he was just a realty-TV star whose comeback myth made him a patron saint for a certain class of American dreamer.

“I related to him,” Sayoc told a psychiatrist after his arrest. “Trump is for the forgotten people.”

Even among the throngs of Trump fanatics who emerged during the 2016 campaign, Cesar Sayoc stood out. With a hulking frame and arms that could bench-press nearly 500 pounds, Sayoc wore a red MAGA hat, chanted “Lock her up!” at rallies, and handed out Trump-for-President flyers on the streets. He custom-made his own posters (clinton paid domestic terrorists to incite violence and pretend to be bernie supporters), plastered them onto his van, and drove this makeshift MAGA-mobile through his South Florida community. He bombarded friends with pro-Trump social-media posts. His entire schedule, in fact, revolved around MAGA commitments. He’d be at the gym in time to watch Fox & Friends each morning, and he’d be back in front of the TV for Sean Hannity’s show in the evening.

Sayoc’s reverence for Trump, according to his lawyers, was rooted in deeply personal forces. Donald R. Jones, who’d represented Sayoc in the past, told the judge in the bombing case that throughout the 2016 campaign, Sayoc “became more and more attached to the belief that the cause of ‘making America great again’ through Trump’s election would somehow also include making the unfair world he had previously been exposed to by weak men in his life better.” For Sayoc, 56 and suffering from the traumas of his past, the celebrity wasn’t just a would-be President. “Sayoc found in Donald Trump,” Jones added, “a sort of surrogate father.”

Sayoc’s own father had abandoned the family when Sayoc was around five. His parents owned a household-goods business; Cesar Sr. would disappear for months at a time, telling his family he was building a factory in the Philippines, his native country. In reality, he was living a double life, off spending his wife’s earnings on gambling, drugs, and other women. While the couple was divorcing, Cesar Sr. promised his son he’d return to take him to the Philippines one day. This, too, was a lie. Cesar Sr. never paid alimony. He didn’t call. He never even sent a birthday card. As Sayoc waited for his father to come home, he became distant and withdrawn. He threw tantrums, and his schoolwork declined. In 1973, growing concerned, his mother sent him to St. Stanislaus, an all-boys Catholic boarding school in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi.

Shortly after he enrolled, Sayoc began begging to come home. His mother considered the 11-year-old’s distress part of a normal adjustment to a new school. In reality, something much more sinister was going on. A priest in charge of Sayoc’s dorm, according to court documents, was sexually abusing her son. The abuse began with inappropriate touching, then escalated. “He started kissing me,” Sayoc told the psychiatrist during the mail-bombing case, “and then he would take my pants down and anally rape me.”

Sayoc looked for help within the school, but according to the court records, no one believed him. “I would wear three or four pairs of pants during the day to protect myself,” he told the psychiatrist. Eventually, Sayoc made a desperate call to his mother one night after he’d been molested. Though he wouldn’t explain the source of his misery—“You are supposed to protect the church”—he insisted that if she didn’t let him come home, he’d kill himself. His mother relented, but it would be more than 35 years before she learned the details of her son’s trauma. (Sayoc sued the school in 2013, and the parties settled.)

According to his court filings, Sayoc was born with serious cognitive problems and learning disabilities, including dyslexia. “I hate to say this,” his sister Christina admitted in a letter to the judge, “but his intelligence level was quite low.” Meanwhile, as a shy, skinny teenager who spoke with a stutter, Sayoc was an easy mark for the bullies at North Miami Beach High School. Before long, though, he found a way to protect himself.

Sayoc, then 15, started using steroids, popping pills at first before moving on to needles. “You are supposed to take them only once a week,” he told the psychiatrist. “But I was injecting myself every day.” According to a report from an expert in steroid use included in the defense’s filings, the sexual trauma Sayoc endured at St. Stanislaus “may well have contributed to his resolve to be bigger and stronger and never again be a victim.”

By the early ’90s, Sayoc was working in South Florida strip clubs, first as a bouncer and eventually as a performer. For a guy who was naturally shy—often described as a gentle, even docile, giant—the jobs held a particular appeal, helping him get over his fears of approaching women. The longer he worked in the industry, though, the more pressure he felt to build muscle. He ratcheted up his steroid use, injecting himself with human growth hormone and consuming as many as 170 vitamins a day. While the drugs helped him feel safe from predators, they also triggered volatile mood swings. “Sometimes,” he told the psychiatrist, “[I] feel like I’m going insane.”

“While traveling the country as an exotic dancer, he married a fellow stripper, then split from her three months later. He opened

a dry-cleaning business, and it collapsed shortly thereafter.”

In 1994, while living with his grandparents, Sayoc pushed his grandfather to the ground during an argument. “I was so jacked up on steroids,” Sayoc told the psychiatrist. “They had to call the sheriff to get me out of the house.” A few years later, during a dispute with the electric company, Sayoc threatened to blow up the utility if it turned off his power, telling the customer-service rep, “It would be worse than September 11.” Sayoc was arrested; he pleaded guilty to one count of making bomb threats and spent a year on probation. Despite it all, he couldn’t bring himself to quit the steroids. “It made me feel strong and good about myself,” he told the psychiatrist. “I felt I really needed them.”

Sayoc’s adult years were defined by failure. While traveling the country as an exotic dancer, he married a fellow stripper, then split from her three months later. He opened a dry-cleaning business, and it collapsed shortly thereafter. With his strip-club earnings, he eventually bought a $385,000 house. But during the 2008 recession, he lost his job, watched his home go into foreclosure, and moved into his van.

Before the mail bombings, he was arrested at least nine times for various offenses, including car theft and shoplifting. “He was just kind of like a sad-sack situation,” says Scott Saul, a lawyer who once represented Sayoc. “His only prior [charges] were probably because he’s poor and he’s stealing from Peter to pay Paul.” (Sayoc does have one violent-crime conviction—for a battery charge related to one of his thefts.) In 2012, Sayoc filed for bankruptcy. Homeless, estranged from his family, and mentally unraveling, he considered taking his own life. “And then,” as he told the psychiatrist, “here comes Donald Trump.”

Sayoc first became familiar with the celebrity real-estate mogul through his audiobooks. When he was at his darkest point—cooking meals in a portable crockpot and showering at the gym—he began listening to them “obsessively,” as a way to cope with the trauma of his sexual abuse, according to documents filed in his 2013 lawsuit against St. Stanislaus. As Sayoc explained in a letter to the judge in the mail-bombing case, “I was deeply depressed, low self esteem, confidence, self worth, anxiety, panic, phobias, psychologically damaged, scared for life, a growing rage anger, let down, antisocial, loner, etc. A lot of people who have gone through what I have gone through do not make it.” The arc of Trump’s success resonated. As Sayoc told the psychiatrist, “[Trump] lost $952 million and now he is a billionaire.”

Sayoc credited Trump with saving his life. Listening to Think Like a Billionaire: Everything You Need to Know About Success, Real Estate, and Life, and Trump: How to Get Rich inspired him to work multiple jobs and try to get back on his feet. He went to a Trump-sponsored career-advancement seminar, tuned in to Trump’s TV shows, and bought Trump-branded business suits. According to Sayoc’s defense attorneys, Trump came to represent “everything [Sayoc] wanted to be: self-made, success-

ful, a ‘playboy.’ ”

It wasn’t the first time Sayoc had reinvented himself—he’d fabricated whole new identities before. In 2014, in the course of a lawsuit against an acquaintance, Sayoc claimed he had booked shows for the Chippendales, played soccer in Italy for A.C. Milan, trained under professional wrestling coach Eddie Sharkey in Minnesota, and been middle linebacker for the Arizona Rattlers of the Arena football league. “All my peers sought me out for advice,” he stated, “because I was that kind of a leader that, you know, I’m not practicing all week to lose on Sunday.”

For years, Sayoc also falsely claimed to be of Native American descent. According to Ron Lowy, a lawyer who represented Sayoc in earlier matters, the ruse was linked to Sayoc’s father’s abandonment, which filled him with feelings of inadequacy. “So in order to try to complete himself, he decided to create an identity,” Lowy says, “even though it was one that had no relationship to reality.”

Politics, however, wasn’t of much interest to Sayoc. Prior to 2015, he didn’t vote or go to political events. But once his personal idol jumped into the 2016 contest, Sayoc could focus on little else. He attended rallies in Fort Lauderdale, Miami, and Chicago. “The first thing you hear entering Trump rally is we are not going to take it anymore, the forgotten ones, etc,” Sayoc said in a letter to the judge. “You met people from all walks life, creed, color, etc. It was fun. It became like a new found drug.”

After Trump the candidate called Mexicans “rapists,” Sayoc’s own racist views took on a Trumpian flavor. During a 2015 get-together with his former junior-college teammates—Sayoc had been a soccer star before dropping out of college—he alarmed his old friends. “He was saying things like, ‘Build a wall to keep all the Mexicans out,’ ex-teammate Eddie Tadlock told the New York Times. In 2017, Sayoc took a second job at a pizza shop. His manager, Debra Gureghian, told the Times that he spoke admiringly of Adolf Hitler, insisted that Hispanics and African Americans were taking over the world, and—repeating Trump’s infamous conspiracy theory—alleged that President Obama wasn’t a US citizen. “When he found out I was a lesbian,” Gureghian, the pizza-shop manager, told the Miami Herald, “he told me I should burn in hell and I was a deformity, that God made a mistake with me and I should go on an island with Hillary Clinton and Rachel Maddow and Ellen DeGeneres and President Barack Obama and all the misfits of the world.”

“With their Fox News defense, lawyers argued that the President and his media cheerleaders had essentially driven Sayoc over the edge.”

In 2017, Sayoc traveled to DC for Trump’s inauguration. Over the next year and a half, he grew increasingly obsessive and unstable, according to pleadings made by his lawyers in their request for leniency. They argued that some of the blame for Sayoc’s actions lay with the pro-Trump media, which was allegedly filling his already-troubled mind with conspiracy theories and disinformation. This became part of Sayoc’s defense—call it the Fox News defense, arguing that the President and his media cheerleaders had essentially driven Sayoc over the edge.

The attorneys said he was linked to hundreds of right-wing Facebook groups, many of which promoted “the idea that Trump’s critics were dangerous, unpatriotic, and evil.” His lawyers singled out Sean Hannity, whose cable-news program Sayoc watched each night and who told viewers at one point that a large “number of Democratic leaders [were] encouraging mob violence against their political opponents.”

The defense also pointed to the President himself, who frequently called out his political adversaries by name. In mid-2018, for example, Trump claimed in a tweet that Maxine Waters—a future Sayoc victim—“has just called for harm to supporters, of which there are many, of the Make America Great Again Movement. Be careful what you wish for Max!” (Days earlier, the congresswoman had said: “If you see anybody from that cabinet in a restaurant, in a department store, at a gasoline station, you get out and you create a crowd and you push back on them and you tell them they’re not welcome anymore, anywhere.”)

On account of his cognitive limitations and mental illness, his lawyers argued, Sayoc was unable to tell the difference between hyperbole or conspiracy theory and the truth. As he put it in a letter to the judge, “I was getting so wrapped up in this new found fun drug.”

As Trump cast himself as an innocent victim of “fake news” and corrupt Democrats, Sayoc came to believe he was being targeted, too. In 2018, he was working a new second job as a deliveryman for Papa John’s when a deliveryman for the pizza chain was shot and killed in New York City. The murder occurred not long after the chain’s founder had been in the news for making racist comments. As a result, according to his defense filings, Sayoc concluded that delivery people like him were being systematically executed in retaliation. Sayoc also grew concerned that Antifa militants were out to get him. When his van was vandalized, he became convinced that all his pro-Trump images had spurred liberals to smash his window, slash his tires, and cut the fuel lines in an attempt to kill him. He reported the crime and afterward no longer felt safe sleeping in the van. “I felt that all of the Democratic Party leadership,” he told the psychiatrist, “was encouraging attacks on my van.”

As the paranoia became all-consuming, Sayoc used his Facebook account to spew threats against America’s most visible critics of Trump: “Death Death Death to all Clintons,” “Your Days are number Steyer…,” “Di Niro will vanish soon,” “Death to Obama criminal Soros socialist paid puppet.” Offline, meanwhile, he sought the assistance of the supernatural.

For nearly 20 years before then, he’d made regular visits to the South Florida botanica of Lisa Massa, who used Santería rituals to address Sayoc’s various troubles. Once, Sayoc told the psychiatrist, he asked her to help expunge his criminal record and she conducted a ritual that involved placing handcuffs on a plate. “She is gifted with powers,” he said. After Trump launched his presidential campaign, Sayoc put Massa’s influence to work in the political arena, paying her to perform candle-burning rituals intended to benefit his candidate.

There were also rites, Sayoc claimed, targeting Trump’s enemies. “When the Democrats wished bad on Donald Trump,” he told the psychiatrist, “she did a reverse wish so that bad would come to the Democrats.” Sayoc said he’d assist with these “reverse wishes” by buying Massa’s special candles—which ranged from $20 to $65—and lighting them in his van. “Sometimes,” he told the psychiatrist, “I would do 20 candles at a time.” (Massa confirms the pro-Trump rituals but denies performing rituals involving any other political figures.)

At some point during Sayoc’s breakdown, he resolved to take more drastic action. In 2017 and 2018, according to federal prosecutors, Sayoc plugged a number of alarming terms into Google: “How to kill all democrats,” “Kill George soros head off,” “Kill all socialist.” In March 2018, he searched the phrases “What a letter bomb” and “How do they make letter bomb”; among the results was a YouTube video labeled “demonstration of a letter bomb.” Sayoc clicked on it. He bought PVC pipe, electrical wiring, digital alarm clocks, fireworks, stamps, and envelopes. From the inside of his van, he assembled what prosecutors described as 16 improvised explosive devices. He looked up the addresses of his victims online, slipped each device into an envelope, and labeled them with the return address of Florida Democratic congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz. On October 17, 2018, he mailed the first of his 16 packages.

“In my delusions,” Sayoc said in a letter to the judge, “I felt this was a way to get these people off my back.”

As FBI agents scrambled to unmask the MAGA bomber, Sayoc appeared to revel in his work. After his first bomb was discovered at George Soros’s home, Sayoc texted a link to a Times story about the incident to 18 people. By then, he’d already sent most of his homemade explosives. But during the four days between the discovery of the Soros bomb and his arrest—as a panicked nation remained glued to the nonstop news coverage of the bombings—Sayoc mailed at least four additional explosives. At one point, a security camera captured Sayoc watching a CNN broadcast about his attacks. He was grinning.

On October 26, 2018, Stacy Saccal, general manager at the Ultra Gentlemen’s Club, woke up to a call from one of her bartenders saying, “Turn on the news.” She flipped on the TV and gasped, “Oh, my God. It’s really him.” Federal law-enforcement officials had tracked Sayoc to Florida after finding his fingerprint on the envelope of a bomb he’d mailed to Maxine Waters. By the time Saccal got to the strip club, the satellite trucks had already arrived.

The spectacle of his arrest upended the lives of Sayoc’s stunned family. After federal investigators seized his mother’s computer, she was unable to run her cosmetics business and, according to Lowy, it subsequently shut down. Neighbors in her Florida condominium, concerned that bombs may have been built on the property, accosted her. “She had been the condominium president,” says Lowy, who represented the family, “and overnight she was the pariah of the building.”

Sayoc was sent to a federal detention center in New York and placed in solitary confinement, where his mind deteriorated further, according to the psychiatrist’s report. He heard voices and saw electricity shooting out of inanimate objects. After telling his mother in a recorded phone call that he tried to hang himself, he was placed on suicide watch. According to the psychiatrist, Sayoc was suffering from severe personality disorder and steroid-induced mental disorder. With the help of antianxiety medication, he became more stable.

Authorities eventually recovered his DNA from 12 of the bombs that Sayoc had dropped in the mail. His defense lawyers maintained all along that Sayoc had built the devices only to terrify his victims, rather than injure them. Borrowing one of Trump’s signature terms, they claimed the packages contained “hoax” bombs. Still, in pleading guilty, Sayoc admitted being aware of the risk that they might explode. “Now that I am a sober man,” he told the judge at his sentencing, “I know that I was a sick man.”

In August 2019, Sayoc was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison. The judge explained that in deciding against a life sentence, he took into account Sayoc’s mental disadvantages and sexual victimization. But he also agreed with the defense’s argument that Sayoc intentionally designed the bombs so they were unlikely to detonate.

It will be a long time before Sayoc can hitch his wagon to another political candidate. But the specter of the MAGA bomber looms over the 2020 election. As Sayoc’s former attorney Ron Lowy sees it, the country is filled with potential bombers, damaged souls who need just a little nudge from their favorite Facebook group or talk-show conspiracist, or maybe even their favorite President. “[Trump] should realize there are sick people out there,” Lowy says. “People that are susceptible to this.”

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)