Ben Sasse made waves Wednesday with a proposal in the Wall Street Journal to reform the US Senate. Writing that it’s time to “think big,” the junior Senator from Nebraska offered ideas as boring as abolishing standing committees—and as wildly fun as press-ganging 100 senators to live inside a single dormitory. (Here at Washingtonian, we are big fans of this idea).

But Sasse is taking it in the teeth from liberals and progressives alike when it comes to his most radical idea: Abolishing the 17th Amendment, the part of the Constitution that allows for the popular election of senators. Before the amendment passed in 1913, senators were chosen by state legislatures. Left Twitter has not been kind to Sasse’s idea:

What's amazing about that Ben Sasse op-ed is the subtext: Mr. Civic Virtue turned hacky Trump Enabler is basically blaming…his voters for his own moral cowardice, begging to be freed from democratic accountability to he can be the Good Decent man he knows himself to be.

— Chris Hayes (@chrislhayes) September 9, 2020

The movement to popularly elect senators came at the height of the Progressive era, when activists were primarily concerned about corruption. A wave of scandals had convinced many Americans that Senate seats could be bought and sold by corrupted state legislatures, whose leadership could be easily manipulated by organized money.

But Sasse’s concern in 2020 isn’t corruption. It’s partisan polarization. “Today—thanks to the internet, 24/7 cable news and a cottage industry dedicated to political addiction—politics is polarized and national,” Sasse writes. “That would change if state legislatures had direct control over who serves in the Senate.”

Sasse is correct that the so-called nationalization of American politics is a serious problem. But Sasse is probably wrong if he thinks that devolving the election of senators to 50 separate state legislatures would be any solution, or make the Senate any less polarized. If anything, Sasse’s idea would probably make things worse.

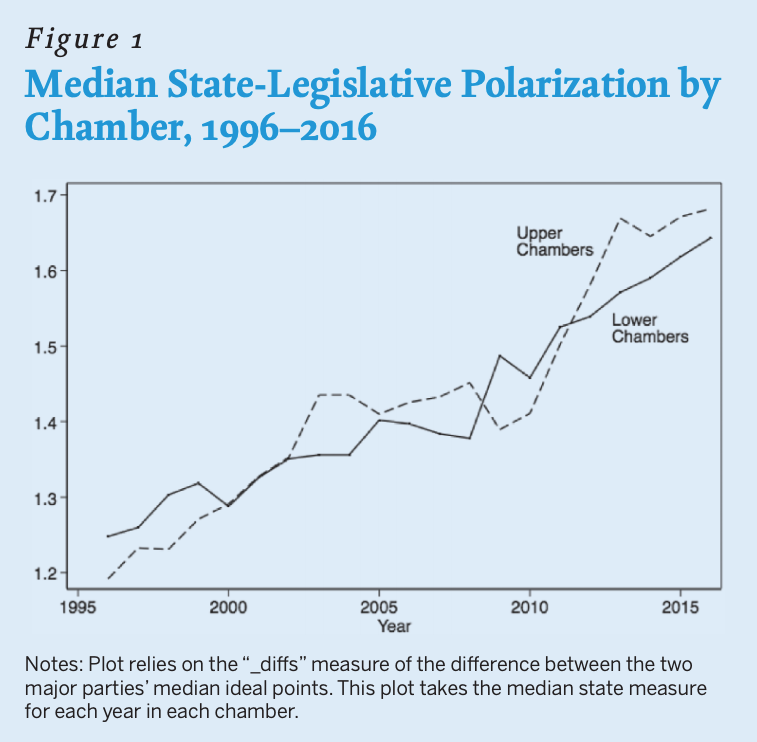

The reason is that state legislatures are just as polarized as the rest of the country, including Congress itself. Over the past 15 years, as political scientists have observed a steep rise in partisan polarization in all aspects of American public life, their research has documented a similar climb in polarization inside state legislative chambers, too.

This is largely due to the work of two researches, Boris Shor and Nolan McCarty, who have tracked partisan polarization in legislatures since 2011. By using a median scoring system, Shor and McCarty have demonstrated that, while polarization is far from uniform across all 50 states, state legislative chambers are about as politically polarized in their voting behavior as Congress is. (In 2014, Shor found that about half of state legislatures were actually more polarized than Congress.) Seth Masket, a professor of political science at Denver University, summarizes the research this way: “As clearly shown in the figure [below], polarization has proceeded apace at the state level, mirroring national-level trends during the same period.”

That research confirms what journalists and government groups have been observing for several years. As legislatures become dominated by one party or another, their legislative behavior tends to become more extreme. And the possibility for mixed chambers also seems to have diminished. Today, 48 states see their legislatures controlled by a single party. (Minnesota is the only state in the country with a divided legislature.) And when it comes to controlling those legislatures, Republicans have a big advantage over Democrats, 29 to 19.

This all makes Sasse’s proposal to reduce partisanship—which it probably won’t do—sound merely like a Potemkin argument to just get more Republicans elected to the Senate. And in any case, it certainly won’t turn the dysfunctional upper chamber into a bastion of comity and fellow feeling.

But it’s worth pausing to consider what would happen if the United States did abolish the 17th Amendment—and whether the ramifications wouldn’t, in fact, benefit Democrats in the long run.

If state legislatures were tasked with electing US senators, it’s easy to imagine what would happen next: state legislatures would become even more polarized than they are now. If local elections suddenly carried the weight of choosing the next senator, national media would congeal far more often around close state elections or contested chambers. PACs and SuperPACs would pour money into tight races. National political figures would fly into the local airport and squeeze in a stump speech or two for a besieged local incumbent.

In short, we’d likely see the phenomenon of what researcher Dan Hopkins calls “nationalized” politics—the growing tendency of Americans to vote for their party tribe, from president to county coroner—seep even further into state contests, turning extremely local state elections into quasi-national events.

Whether this is a good thing or not, there’s at least one group in America that would benefit a lot from this kind of newfound passion: The Democratic Party. Because voter turnout is far lower in local and odd-year elections, and because the large majority of state legislatures—39 out of 50—are elected in odd-year or non-presidential election years, state contests have long showed higher Republican turnout than Democratic. (There are many hypotheses to explain this, but one is that local politics is all about place-based social investment—and wealthy voters are more likely than poor voters to be homeowners.)

Whatever the reason, political analysts like Sasha Issenberg have argued for years that Democrats need to become more passionate and mobilized around local and state elections. Other analysts, like the writer Joseph O’Neill and professor Eitan Hersh at Tufts University, have argued for versions of a post-Trump Democratic party, one that is heavily invested in machine politics at the ultra-local level. As Hersh writes in his book Politics Is for Power, for Democrats to succeed in small communities as well as big cities, they “need robust, long-term party engagement,” adding, “that’s what they lack in communities all around the country.” Nationalizing local elections as part of a greater struggle for control of the Senate would certainly bring Hersh’s vision closer to reality.

And while the divide of state legislatures certainly gives an advantage to Republicans today, it’s not a dramatic advantage, nor a permanent one. True, if legislatures could pack the Senate today, Democrats might have 39 Senate seats—six fewer than they currently have. But state legislatures would choose senators every six years. And in a world in which national parties are deeply invested in local races, it’s far from obvious that Democrats couldn’t recoup this deficit, or do even better.

By increasing the perceived electoral importance of state legislatures, abolishing the 17th Amendment could conceivably have other positive effects. In research published last year, Masket of Denver University identified the key factors that have caused the growing partisanship in state legislatures. One of the biggest culprits: the corrosion and death of once-robust local newspapers and journalism outlets. Masket summarizes research showing that when more reporters and outlets are covering legislative districts and state houses, the more diminished partisan polarization becomes. So perhaps giving state legislatures the power to choose the Senate might spawn a rebirth of the interest and funding for local journalism.

But these suppositions would be the result of heightened polarization, not the outcomes of diminished polarization in the Senate—as Sasse tries to argue. Masket finds that idea hard to swallow. Increasingly, state races seem to hinge as much on national politics as local issues. In an email, Masket described his research into the 2018 gubernatorial contest in Colorado. “The main issue most voters seemed to care about, across both parties, was how the new governor would treat President Trump!” Masket wrote. The point, he said, is that “putting state politicians in charge of US Senate elections means that state politics will revolve even more around national issues”—not less, as Sasse believes.

So going back to the days when state governments got to choose their senators probably won’t improve the Senate’s partisan blood feud. That would just be moving the source of the Senate’s gridlock from the partisan frying pan into the partisan fire. But in a hyper-partisan world—which shows no signs of changing—that might not be such a terrible thing for Democrats.