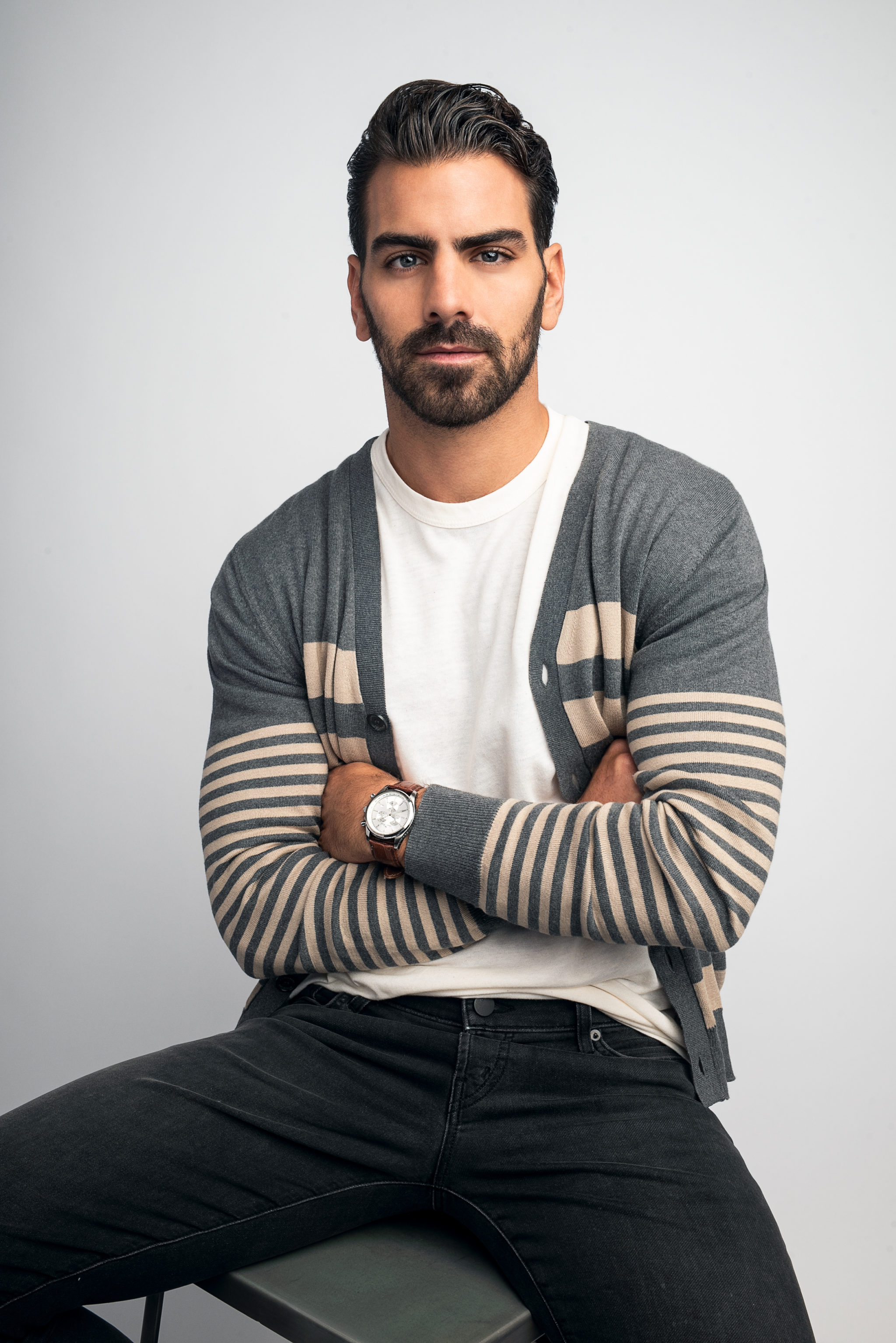

With his smoldering looks and killer rumba moves, Nyle DiMarco won two high-profile reality shows within the span of six months: America’s Next Top Model in late 2015 and Dancing With the Stars the following May. He was the first deaf person to top either competition. Now DiMarco is involved with another reality show—but of a very different variety. The new Netflix docuseries he has created, Deaf U, trades dance-floor fireworks for campus high jinks, capturing student life at DiMarco’s alma mater, Gallaudet, the DC university for the deaf. “Gallaudet really needed a reality show,” DiMarco says in sign language through an interpreter. “It’s not just about the deafness. There’s so much drama, so many layers, and such a range of diversity within our community.”

Premiering October 9, Deaf U follows the social lives of seven students as they navigate personal trauma, gossipy friends, and casual sex. The series is addictively entertaining, but it’s also meant to draw attention to the broader world of deaf education. DiMarco, an executive producer, is from a multigenerational deaf family and grew up using American Sign Language. That’s rare, though: The vast majority of deaf children in the US are born to hearing parents. “I’ve met deaf people who had no background in sign language, but they lived ten minutes away from a deaf school,” he says. “They didn’t know there were other deaf people out there using a language and having a culture. That information has been withheld from those people. I’m working to change that.”

But Deaf U also offers plenty of unfiltered antics: messy hookups, sloppy drunkenness, even cornhole at Wunder Garten. Pre-pandemic DC plays a big role: Cameras follow cast members to a fire pit at the Wharf, the dance floor at Rosebar, and a slam-poetry night at an outpost of the local restaurant/bookstore chain Busboys and Poets. “I hope that people see that in the deaf community, deafness is not really a disability,” says Alexa Paulay-Simmons, the student at the center of a lot of the show’s drama, through an ASL interpreter. “It’s more of an identity.”

DiMarco’s next projects likewise focus on the deaf community. He’s developing a Netflix doc on a deaf football player as well as a movie about the heated 1988 protests that arose after Gallaudet appointed a president who wasn’t deaf. He’s also working on a sitcom in which he’d star. DiMarco hopes to help the entertainment industry “see that it is possible to write deaf characters—that we’re not just a monolith,” he says. “Deaf people face the same things that hearing people do every day.”

This article appears in the October 2020 issue of Washingtonian.