Carrie Brady, as told to Susan Baer:

Racing into my car, barely able to breathe, I grabbed the first thing I could find to write on—the inside cover of my What to Expect the First Year book—and started scribbling the words coming at me on the phone. “Pulmonary hypertension” . . . “chest compression”. . . “brain damage & don’t know what future holds . . . .”

I had darted out of a birthday party for my friend’s six-year-old son when I got the call. Beth* was the adoption agent for the mother whose baby I was to adopt, and I had a bad feeling. Why was Beth calling me on a Sunday, weeks before the due date? Had the birth mom backed out? The news was worse. The mother, Anna,* had hemorrhaged and given birth in an emergency C-section—five days earlier!—and hadn’t informed anyone. She was fine, but the baby, who’d aspirated blood and been without oxygen, had been helicoptered to a hospital in the mother’s home state down south and might not survive.

Beth told me to stay put in Washington. There was nothing I could do.

The next morning, she called again: The baby had flatlined twice overnight. The birth mother had signed the adoption papers giving up all parental rights, so Beth’s agency was now the guardian. Again, she told me to stay put. The baby was not expected to make it.

Sobbing and bewildered, I went for a walk, made a couple calls—and got on a 5 pm flight to the hospital.

I made the decision to adopt more than three years ago while running product strategy for Google Cloud in London. I had turned 40 and hadn’t yet found anyone I wanted to spend my life with. Everything else had fallen into place. I made sure of that. The middle child in a flag-flying Catholic family in Cleveland, I had earned a soccer scholarship to the University of Michigan, where I was a starting player as a freshman, and completed a five-year engineering program in four years. After college, I took up long-distance racing, racked up marathon and duathlon championship titles, and in 2005 was among the top ten finishers in my age group in Hawaii’s famed Ironman triathlon.

I’d always had boyfriends. My college sweetheart was quarterback of the Michigan football team—the “wrong quarterback,” friends joked, because the other Michigan QB was Tom Brady (no relation but a college classmate and friend). But my romantic relationships never went the distance.

I knew adopting a baby on my own would throw my tidy life into disarray, and friends and family reminded me of that daily. “Why do you want to uproot your life like this?” my mother asked repeatedly. And even: “How will you feel if your child isn’t good at sports?” But after attending an information session, I knew adoption was what I wanted. I felt I could give a different sort of life to a child born into tough circumstances. For the first time, I wasn’t embarrassed about being 40 and single. I didn’t have a guy, but why did creating a family have to go in a certain order?

So I left my job, left London, and in July 2017 moved to Washington, wanting the support of my sister, who lived here, as I started the process. She and her family would soon move to Texas, so I crashed in a friend’s basement in Chevy Chase. Jobless and basically homeless, I’d never been more sure of my purpose.

With international adoption more difficult, as many countries have either closed their doors or tightened regulations, I opted for a domestic adoption. The first thing I learned was that if I wanted to be a mother anytime soon, within two years or so, I’d have to consider a baby who might have some drug dependency. Over the last several years, because of the opioid epidemic, a growing number of infants placed with adoption agents in the US—as many as 60 or 70 percent at some agencies—have had exposure to drugs or alcohol in utero, mostly opioids or treatment drugs such as methadone. The opioid crisis has had such a profound impact on the adoption landscape that placement agencies provide classes on prenatal drug exposure so prospective parents can decide whether it’s something they can handle. I decided I could.

I knew adopting a baby on my own would throw my tidy life into disarray, and friends and family reminded me of that daily. “Why do you want to uproot your life like this?” my mother asked repeatedly.

By the end of 2017, I’d rejoined Google in Washington, rented a two-bedroom apartment in Georgetown, and tackled the blizzard of adoption paperwork. In March 2018, much sooner than I expected, I received an e-mail from my adoption consultant: “BM [birth mother] Anna due with Baby Girl in summer 2018—wants a single parent.” My heart leaped. Anna had placed other children for adoption and was on medically prescribed methadone as treatment for a drug addiction. I knew that meant her baby would likely be born dependent on methadone and go through a period of withdrawal.

Still, when Beth told me Anna was open to a text exchange with me, I reached out immediately.

Me: “Hi Anna, it’s Carrie. I just wanted you to know how grateful I am you picked me 🙂 Bless you!”

Anna: “Ur welcome thank u. I’ve never talked to the family before i really hope u enjoy being a mom and im happy i am able to be the one to do that for u

“Here are ultrasound photos. She is a thumb sucker – I will send more when I get them”

Me: “Anna!!!! You are amazing! I love these! You just made me tear up at work. Yes! I’d love to see whatever you are comfortable sharing. No pressure! Thank you 🙂 She is Beautiful.”

I was ecstatic, but over the next three months, our exchanges were increasingly troubling. Anna wrote that the birth father was beating her. She frequently talked of being sick. She made specific requests about the baby’s name. In April, she asked if I would come meet her, even suggesting we go to an “all-you-can-eat crab leg place” because that’s what she’d been craving. I bought a plane ticket and booked a hotel room, but she canceled the day I was to fly down, saying she had strep throat.

I began worrying even more.

Me to Beth: “I was rereading Anna’s prior doc appointment notes and she always refuses to give urine sample bc dehydration. Makes me wonder if she is hiding something — still taking more or other drugs?”

Beth: “I think it’s a strong possibility she is hiding something.”

Me: “Crap.”

Beth found out Anna had been taking benzodiazepines such as Xanax and Klonopin—whatever she could buy on the street—in addition to her methadone. At some point, she also stopped going to the doctor.

Adoption is a control freak’s worst nightmare. It was excruciating to have such a tenuous grasp on something so important, and hard not to read too much into every unanswered text or canceled date. My adoption consultant told me to hang in there: “It’s not a bad thing to be all in.”

I confided to my sister my worry that if this baby survived with major brain damage, it was going to be too much for me.

Remaining hopeful, I prepared, scheduling maternity leave, hiring a nanny, interviewing pediatricians. I was too superstitious to get too much gear but bought a stroller and car seat and daydreamed about one day having a baby shower.

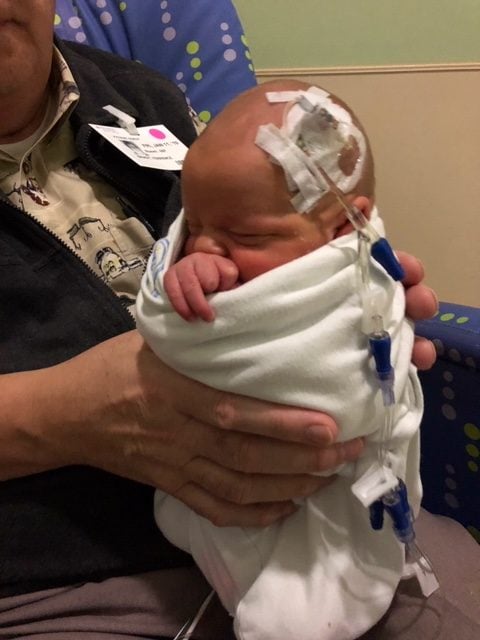

And then, after learning that the baby had flatlined and Anna had given up her parental rights, I raced to a hospital hundreds of miles away to meet the baby girl with peach-fuzz hair. She was in a specialized neonatal intensive-care unit for drug-dependent babies, tethered to a tangle of technology: goggles to shield her eyes from the lights; mini-earmuffs to dull the sounds; a breathing tube down her throat; and other tubes, monitors, and catheters all over her caramel-colored body. Doctors had resuscitated her twice but hadn’t given up hope.

By midweek, my sister and parents had flown in to be with me. My whole rationale for adoption was to be the best mom for whatever baby I was matched with. But now I confided to my sister my worry that if this baby survived with major brain damage, it was going to be too much for me. I prayed about it and hoped the baby would somehow lead me to the answer. I asked Beth, “Do you ever have families looking for special-needs babies?” She said, “Yeah, I do.”

The baby’s heart stopped again Wednesday night, and doctors again resuscitated her. If you make it through this, I whispered to her, I’m here for you until we find you the right family. But on Thursday, doctors determined there was no significant brain activity. With Beth, they decided to take her off the respirator. Even the nurses were crying.

I wanted to have her baptized, so we called in a chaplain. The nurses brought her a dress and booties, and she was removed from all life support. We were able to hold her, the only time she was ever held. I told her why she was here and how sad I felt. I promised to remember her. For the first time, there were no sounds. The room was still.

I kissed her and handed her back to the nurses. She survived about ten more minutes. Outside the NICU, my sister and I fell to the floor in each other’s arms. I screamed through my tears: What just happened? What do I do now?

Back home, my sorrow was unrelenting. I saw a grief counselor, went to church, took long walks—my form of meditation—but felt lost. My parents implored me to give up. “You’re a better aunt than you would be a mother,” my mom told me, trying everything. She begged me at the very least to amend my profile to exclude drug-addicted birth mothers. A friend told me I was being naive and foolish to continue down such an uncertain road.

Two months later, Beth called: Another birth mother, also from the South, had chosen my profile and was to have a baby boy at the end of the year. She, too, was in a methadone treatment program for a drug addiction. Beth cautioned me that she had placed her last child for adoption only to back out after the birth and keep the baby.

Still grieving—and out more than $40,000 from the first effort—I heard myself tell Beth, “I’m ready.”

Instead of deterring me, the loss of the baby girl made me more determined to become a mother, especially to a drug-dependent baby. Having seen a NICU full of infants shaking and crying with withdrawal symptoms and hardly a birth mother in sight, it was something I felt certain I was called to do.

Me: “Hi Kelly,* Beth sent your email address and said you’d like me to reach out…I know life is busy, so when you get a minute, it would be great to hear more about you and your family plan. Very best, Carrie”

Kelly: “Hi!!! I’m so happy to hear from you!! I was absolutely drawn to your profile instantly! So I guess now you’re in my plan… I am curious to know about how you feel about the Methadone situation. I’ll send you some ultrasound pictures once I figure out where I put them.”

Me: “What a wonderful note to get. Tell me more about the methadone situation. No, it does not freak me out. I would love to hear from you after your doc appt. Xoxo”

Kelly was a thirtysomething white divorced mother, and the father, she’d said, was one of two men—one white, one African American—with whom she’d had relationships. She told me she’d turned to opioid painkillers years ago to handle stress and had become addicted. She’d been on methadone for three years, so her baby would likely be dependent on the drug. Through information provided by my adoption consultant, I knew the detox period could last weeks to months. There wasn’t much data on longer-term effects from prenatal opioid or methadone exposure, but some studies showed none of the developmental problems associated with fetal alcohol syndrome.

Kelly, like Anna, also brought up getting together, so in mid-October I flew to her hometown to meet her, along with Beth, at a Starbucks. Kelly arrived an hour late and told all kinds of stories about her life that sounded fishy. A background check had turned up some unsettling information. Not wanting to rock the boat, I never brought it up.

I spent a sleepless night wondering if going forward was worth the risk of another heartbreak, not to mention the financial strain. But my gut told me Kelly was trying to get her life back on track. She seemed goodhearted. She didn’t ask me for money. I decided to stick with her and worry about only two things: Was she going to a doctor, and would she go through with the adoption?

Her texts were usually upbeat and reassuring.

Kelly: “So I just want you to know that I am super happy to have met you. I am even more excited and confident about my decision. I look forward to you being an awesome mom for this little pumpkin. I’m sending you ultrasound photos.”

Me: “Omg ?. Is that a big or small penis? ??”

Kelly: “Hahahaha… hopefully a good sized one… fingers crossed for little man’s sake!!”

Me: “You are so wonderful. Please take care of you for the baby and for you!”

For the next several months, Kelly was my life. I was at her beck and call, and we texted almost daily. In December, as the due date neared, I made another trip to her hometown and joined her for a doctor’s appointment. I told her I’d decided to name the baby Grayson, and she loved it. We decided it would be our secret until he was born. I gave her a necklace that matched one I’d bought for myself—a slim gold bar engraved with a small G. It was one of the best days ever.

Christmas and New Year’s came and went. With Kelly more than a week overdue, doctors planned to induce her. I flew down the day before the scheduled delivery and took Kelly to a hospital with a specialized NICU for babies with “neonatal abstinence syndrome,” or NAS. On the way, we stopped at a 7-Eleven, where she bought two huge chocolate bars and bags of Skittles and Starbursts. She used her rewards card when I paid, which spit out a bunch of coupons for cigarettes. I’d suspected she was a smoker—she’d even smelled of cigarettes when I’d picked her up that day—but she’d always denied smoking during the pregnancy.

The day of the birth didn’t start out well. Kelly was angry and agitated because the hospital was late getting her methadone. When she finally received it, she was a different person. I winced watching her swallow a drug while she was still carrying my baby.

She allowed me to stay for the delivery, so I was by her side all day, fetching ice for her to chew or holding her hand through contractions. Grayson was born around 4 pm—6.9 pounds, 20 inches long. I cut the cord and was the first to hold him. For once, I felt no fear.

I brought him to Kelly and squeezed onto the bed next to her, both of us overcome. “He’s beautiful,” I said. She agreed and, noting his pale skin, quipped, “It was definitely the white guy.” We laughed through our tears.

Grayson was calm from the methadone still in his system. But by the next afternoon, less than 24 hours old, he was having tremors and crying a high-pitched cry I’d been warned about. He tore at his face so violently that nurses had to tape brick-like pads to his hands. I’d been prepared for his pain, but my heart ached to see it. “Buddy, we can get through this,” I told him. “I promise you.”

With everyone’s focus now on Grayson, the dynamic started to shift. Kelly was having trouble letting go of the decision-making. The hospital staff was dealing more with me, and she seemed to feel judged and embarrassed that Grayson was struggling. She kept kissing him, telling him “I love you” and apologizing for his condition. It was very uncomfortable.

I tried to be supportive and respectful. But that night, something was off. Kelly had never been angry with me before but suddenly glared at me and asked to be alone with Grayson. I went back to my hotel, sick to my stomach. She texted, saying I wasn’t who she’d thought I was—the exact words she’d used to describe the couple who’d planned to adopt her daughter. Beth agreed she might be backing out.

In the morning, I went for a walk by the water. I blared two songs in my earbuds—“You Are Not Alone” by Michael Jackson and the country song“Everything’s Gonna Be Alright.” I decided to leave it up to God. If Grayson was meant for Kelly, then I would have to live with that. It took a lot of walking and crying, but I finally convinced myself that the right thing would happen.

When I arrived at the hospital, Kelly was holding Grayson. They looked so peaceful. I told her I just wanted the best for him and would love her even if she wanted to change her mind.

She said no and apologized. We cried and hugged, and she said she was going to go sign the adoption papers and get back to her children at home. Packing up her things afterward, she hugged Grayson and me goodbye. I felt like my heart was going to explode.

My euphoria was short-lived. The lights and noises were too much stimulation for Grayson, so he was moved to an individual room in the NICU. Now that I was family, I could stay at the Ronald McDonald House nearby. Kelly continued to text, and I tried to sound positive, not wanting her to feel guiltier than she already did. But the doctors told me Grayson’s blood had a higher concentration of red blood cells than was normal, a condition that can result from maternal smoking. He was getting fluids through an IV but might need a blood transfusion.

I broached the smoking subject again.

Me: “How much did you smoke with him? For real.”

Kelly: “Practically not at all. Really. Might have had one in a month. Didn’t find out pregnant until 24 weeks or so. Smoked during that time. Maybe a pack a week. Why, what’s wrong now?”

Me: “They think the red blood issue is from smoking. He will clear it. We know he can. It would just be helpful to really understand how much.”

Kelly: “Can’t be from smoking cause the smoking was practically nil.”

Thankfully, the fluids resolved the issue; Grayson avoided a transfusion. But his withdrawal symptoms were escalating. His poor little body was so rigid, I could pick him up by his elbows, and his tremors were brutal. They would start at his feet and work their way up to his head and hands. Every time he started to fall asleep, the tremors would wake him with a jolt, and he’d cry from exhaustion and pain. We swaddled him tightly and put sand weights in his crib—around him and on him—to keep him as immobile as possible.

On Tuesday, his first day weaning from the morphine, the tremors and wailing returned and his body stiffened up again. I was used to this by now, but that night was somehow worse—sadder because we were back to where we’d started.

His crying wasn’t like any baby cry I’d ever heard. Imagine the screams of someone being tortured. That’s what it sounded like—pure anguish—and nothing would stop it. Not a pacifier, not a bottle, not holding or swaddling or rocking him. His nervous system was so sensitive that a rocker was too much movement. Instead, we’d have to hold him upright and gently move him up and down as if on a slow elevator. The nurses told me skin-on-skin contact was the best tonic, but he was so electric, it would take three people to get him to lie against my chest.

I would try to comfort him for about 30 or 40 minutes, and then the nurses would take over for a session—you can’t emotionally handle anything longer.

By Friday, with his symptoms worsening, doctors decided morphine would allow him a little relief.

I had such mixed feelings. With his pain numbed by the drug, he seemed like a “normal” newborn throughout that weekend. He ate and slept. His cry was a typical baby cry, music to me! But I knew it was all temporary.

On Tuesday, his first day weaning from the morphine, the tremors and wailing returned and his body stiffened up again. I was used to this by now, but that night was somehow worse—sadder because we were back to where we’d started.

I tried every trick I could think of to soothe him. Music, tight swaddle, slow warm bath, the elevator move. Nine o’clock, 11 pm, 1 am—he was still miserable. For the first time, with nurses scarce that night, I felt totally overwhelmed and unsure of my ability to cope.

I finally got him into his crib with the sand weights, pulled down one side of the crib to lay my head down next to his, and started singing the country song I’d listened to on my morning walks to the hospital: “Everything’s gonna be alright. Nobody’s gotta worry ’bout nothing. Don’t go hitting that panic button. It ain’t near as bad as you think. Everything’s gonna be alright. Alright. Alright.”

I cried and couldn’t stop. When a nurse finally came in, I asked her to please pick Grayson up so I could take a break. I left the room and called my brother in Las Vegas. “It’s too much—I can’t watch him like this anymore,” I wailed into my phone, sliding down the hallway wall. “It’s too much.”

A nurse saw me bawling in the hallway and encouraged me to go get some sleep. The next couple days were only mildly better—the tremors and other symptoms, even unusual ones like sneezing jags, continued. Babies with NAS receive a “score” that reflects the severity of their symptoms, and his was still high. But by the end of our second week in the hospital, his score had edged down just enough for him to be discharged. The best thing for him now, the nurses assured me, was to be home. It’s the nurture part that gets these babies through, they said.

Because I couldn’t leave the state with Grayson until certain paperwork had been completed, we went to an Airbnb. A week later, we got the green light to go home.

For two more months, Grayson struggled, crying that piercing cry, sometimes for hours on end, clenching up his face and body, and appearing mad at the world for many of his waking hours. He rarely slept more than two hours at a time, and once he started crying, it was hard to get him to stop.

I tried to keep his environment peaceful. I kept the lights low and was careful about who visited. Gentle music—Beethoven or Norah Jones—seemed to calm him. He liked going for walks, so even in February I’d nestle him in the baby carrier and zip my down jacket around both of us. I didn’t venture too far in case he lost it and I’d have to dash home.

Having dug deep into my savings for adoption, I couldn’t afford a regular doula or nurse, but my friends and sister all gave me occasional breaks. Despite my parents’ initial reservations, they became loving grandparents and often came to stay. When I finally had the baby shower I’d hoped for, I brought coffee mugs for everyone with Grayson’s photo and the lyrics that had become my mantra: “Everything’s gonna be alright.”

Soon, it was. In April 2019, as suddenly as snapping my fingers, Grayson got better. At three months old, he would take a pacifier and soothe himself. He started sleeping three and four hours at a time and then through the night. I never heard that awful cry again. Besides normal pediatrician visits, he was seen monthly by a developmental therapist, who dismissed us after about a year: Grayson had hit all of his milestones and showed no signs of any delay.

I don’t know what the future holds for Grayson and me. From day one, I’d never talked to other mothers who’d adopted drug-exposed babies.

About a year and a half ago, we moved to Del Ray, where my living room is now happily cluttered with toys, a giant stuffed bear, and a jogging stroller that my Michigan soccer teammates sent me. With Grayson at my side, I planted a sunflower in the backyard in memory of the baby girl who I believe has been our guardian angel. That is now a summer tradition for us.

And then last December, nearly a year after Grayson was born and more than two since I decided this would be my path, my son and I, along with our nanny, Monica, and good friend Aviva, crammed into a tiny office in a Bank of America in Georgetown to finalize the adoption. Rather than fly to a courthouse where Grayson was born, I was able to have the judge call my cell and, with a notary in the room as a witness, complete the proceedings via speakerphone.

Grayson sat on Monica’s lap and devoured silver-dollar keto pancakes while I answered the judge’s questions. I told her my son now “eats like a professional boxer, sleeps like a teenager, and laughs like every day is the best.” I read some more words I’d prepared, telling Grayson how happy I was for the privilege of a life with him: “I love you more than I ever thought possible. Today’s your day, buddy.”

The judge was tender and kind. “It is my great pleasure to sign the final judgment finalizing this adoption this holiday season,” she said, “making Grayson yours as if he was born to you.”

We all wiped away tears—even the notary. “Thank you for coming,” she said, blotting her eyes with a paper towel. “I have mostly divorces and prenups.”

Monica took Grayson home, and I walked to a coffee shop by the canal before getting on with my day. I hadn’t realized what a burden the uncertainty of the last two years had been. I just wanted to sit alone, experience what it felt like to be without that weight, and let the judge’s words echo in my head: as if he was born to you.

That’s how it has always felt.

I don’t know what the future holds for Grayson and me, of course. From day one, I’d never talked to other mothers who’d adopted drug-exposed babies. I hadn’t wanted to. Why stress about what might happen when I already knew this was going to be my path? I’ll never be far from the memory of how Grayson came into the world. If health issues arise for him at age two or three, or later, I know I’ll wonder if the methadone is the cause. But all that is tucked in the back of my mind. For now, my son is learning new words every day and running all over the backyard with our dog. I’m ready for the marathon.

*Name has been changed.

This article appears in the December 2020 issue of Washingtonian.