The email was short, the kind automatically generated when someone shares an article from a website. It landed in James Zogby’s inbox one day in early 2012. The link was to a story from the Washington Free Beacon. “Hi Zogby,” the message began. “Your friend, Patrick Syring, has recommended this article…”

Oh, God, Zogby thought. He’s back.

Zogby had first encountered him six years earlier. It began with a late-night voicemail at the Arab American Institute, the Washington think tank Zogby had founded in 1995. “I just read James Zogby’s statements online on the MSNBC website, and I condemn him for his anti-Semitism and anti-American statements,” the man declared. “The only good Lebanese is a dead Lebanese. The only good Arab is a dead Arab.”

“F–k the Arabs and F–k James Zogby and his wicked Hizbollah [sic] brothers,” read an anonymous email sent the same night. “They will burn in hellfire on this earth and in the hereafter.”

Zogby didn’t see the messages until he showed up at work the following morning, July 18, 2006, an incredibly hectic moment for the organization. The Israel-Hezbollah War was raging. Lebanon was full of US citizens who had gone to visit relatives and gotten trapped. Zogby, born in America to Lebanese Catholics, was writing columns and going on TV to explain the complicated politics of his ancestral home. His staffers were manning the phone at all hours to help the State Department find and evacuate people.

That night, it was staffer Rebecca Abou-Chedid’s turn to work the phone line. Around midnight, she settled down on the floor of her cubicle to grab a nap when the phone rang: an angry shout—“F—ing Arab!”—and a click as the caller hung up.

The following morning, the director of community relations, Valerie Smith, got her own voicemail: “Hello, Valerie, you f—ing Arab American shit.”

Racist trolls, sadly, were a commonplace in Zogby’s career. In 1980, when he worked for the Palestinian Human Rights Campaign in DC, his offices were firebombed. After 9/11, a man called the Arab American Institute threatening to “slit the throats” of Zogby’s children. The organization hears from so many hate-mail writers that it has long kept a folder for their messages, marked “nuts and crazies.”

Still, Zogby decided to report this one. He got in touch with a contact at the Justice Department after the first threat—“The only good Arab is a dead Arab”—and reported the subsequent flurry of messages, too. A little more than a week later, a Pakistani American man shot his way through Seattle’s Jewish Federation, killing one woman—and AAI’s tormentor used it as a reason to strike again.

“I condemn James Zogby and the AAI,” he wrote in a mass email to the staff, “for perpetrating the murder and shootings.” This time, he signed off as “Patrick in Arlington, VA.”

Zogby’s call to the DOJ wound its way to the desk of Gregory Bristol, a 20-year FBI veteran who had cracked cases of public corruption and chased terrorists and spies. Bristol had just moved from the Enron investigation to a new beat as the agent responsible for covering hate crimes out of the Washington Field Office. In post-9/11 DC, this meant an overwhelming caseload. “The nooses were coming out around then,” he recalls. “One year, we had 100 nooses.”

Against that backdrop, Bristol initially viewed the case as low priority: No one had died or gotten a brick thrown at his head. But there were email addresses and, possibly, an actual name. In one of his earliest voicemails, the caller had identified himself as “Patrick,” plus a last name that sounded a little like “Searing.”

The FBI had woefully inadequate computer search tools at the time, and Bristol had to start by literally going through phone books for names similar to the one in the voice message: Searing, Seering, Syring. Through Google, he did find one Patrick Syring, a State Department employee. The agent didn’t put much stock in it. “I just didn’t think that a person at midlevel management could be doing that,” he says now.

Still, Bristol pulled on the thread. He subpoenaed the email providers, looking for a local match. When the reports came back, they confirmed his Googling. The email subscriber was one William Patrick Syring of Arlington. The man not only worked for State: He was a Foreign Service officer who had served overseas for decades, including two tours in Lebanon.

Bristol started to trail the diplomat—from his Arlington home to the Ballston Metro station, on the Orange Line to Foggy Bottom, then down the couple blocks to State. And then, in the evening, the reverse. It all seemed unlikely: This was a well-dressed and evidently respectable man around 50 years old, living in a placid neighborhood and with no known hate-group activity, just going to his federal job every day. Maybe, Bristol thought, someone had borrowed Syring’s computer—a relative, or a friend staying at the house. As he prepared for the next step—an interview—Bristol believed it still might rule Syring out entirely.

One October morning, the agent followed Syring to Foggy Bottom and cold-called him from downstairs, asking to talk to him either at FBI headquarters downtown or upstairs at Syring’s office. Syring was cordial and calm. He welcomed Bristol up and waved him into a conference room, turning over the “occupied” sign on the door so they wouldn’t be disturbed.

According to his lawyers, Syring’s anti-Arab sentiments took hold during two stints in Beirut in the 1990s.

Bristol sat down at the table with Syring and read aloud the first “Patrick” email to Zogby: “The only good Lebanese is a dead Lebanese . . . . F–k the Arabs and F–k James Zogby . . . .” Syring listened quietly, apparently unfazed, and immediately admitted he had sent it. According to the FBI report summarizing the interview, he told Bristol he felt “disgusted” with Zogby after seeing him on television talking about the Lebanese war. He had found Zogby’s contact info on the AAI website, then called and emailed because he wanted “to intimidate” him, although not—Syring said—to harm him.

Bristol continued, reading all the other emails aloud and playing recordings of the voice messages, and Syring admitted to those, too. He said he’d randomly selected other AAI employees to target, believing that the more people he contacted, the likelier it was that Zogby would see the missives.

Hate isn’t illegal, but death threats such as “The only good Arab is a dead Arab” are, and Bristol knew he couldn’t betray emotion in the interview, lest he risk jeopardizing any part of the confession. But by this point, he had spent more than 100 hours interviewing Syring’s victims and he was suppressing revulsion. “This is a world that we don’t visit often, the hatemongers,” he says. “It’s not a pleasant place to be.” It was galling to hear Syring admit—with no sense of guilt or regret—that he was their troll. “There was no nervousness on his part,” Bristol remembers, “no reluctance.” Syring couldn’t see what he had done wrong.

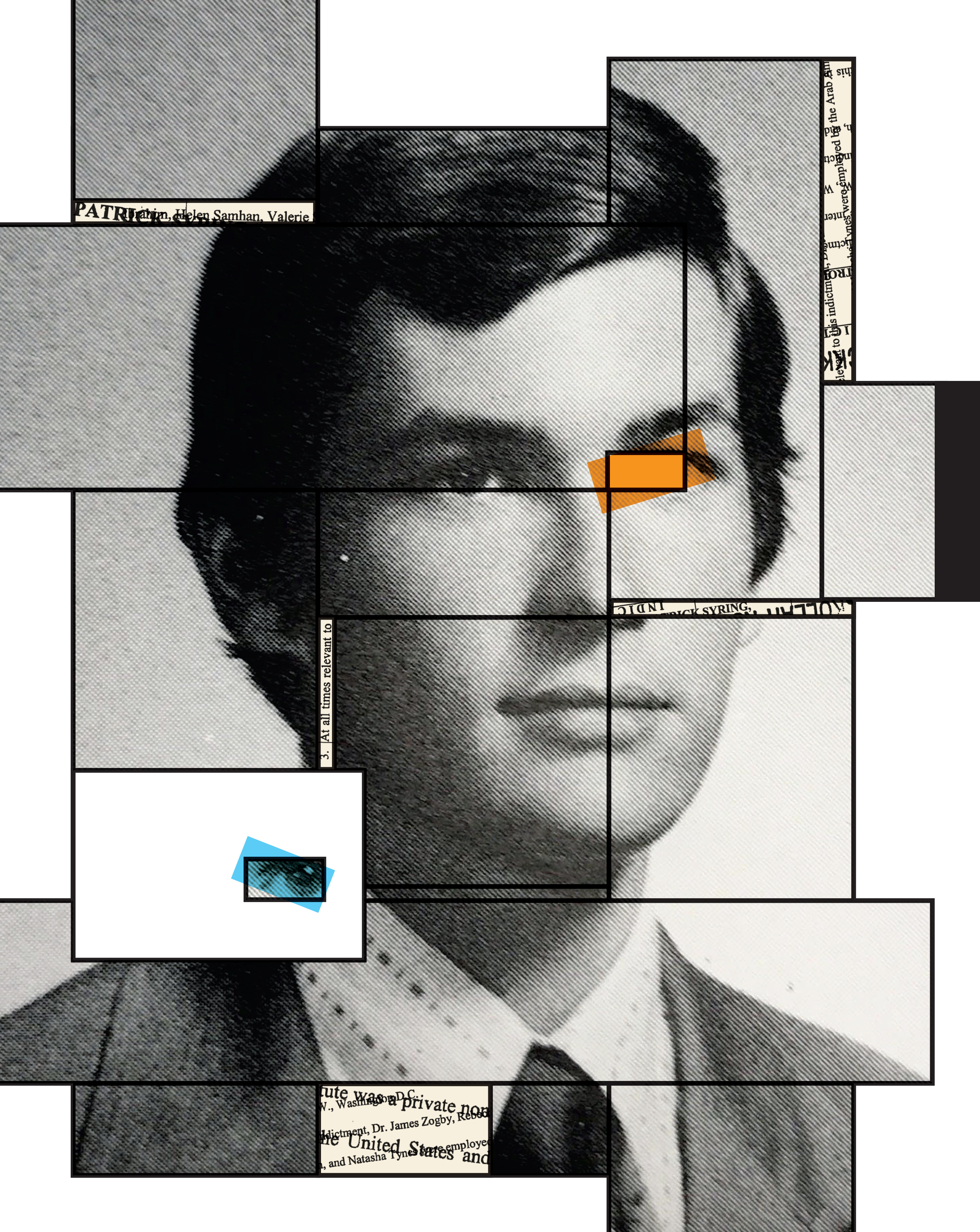

The man who so readily confessed in that State Department conference room had spent more than 20 years representing the United States abroad. Raised in a large Catholic family in Toledo, he had graduated from Notre Dame in 1979 and then from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. He spoke seven languages and had served tours on nearly every continent, working in the consular, visa, and economics offices at posts in Brazil, the Netherlands, Guinea, and beyond. He wasn’t a highflier in State’s bureaucracy, but he was steady. The same held true at home. His Ballston condo was nothing fancy, but he was a loyal, helpful member of the homeowners’ association, the guy whose sidewalk was always shoveled first after a snow.

Many of Syring’s colleagues viewed him as “quiet” or “withdrawn”—“hardly the life of the party,” said one—but that wasn’t necessarily surprising given that he was a gay man who had begun his diplomatic career at a time when staffers could be fired for their sexuality. A diplomat who served with him in Amsterdam in the 1980s summed up the general opinion, calling him “just an ordinary Foreign Service officer, like so many others who were there.” (Through his lawyers, Syring declined to comment for this story.)

What the colleagues didn’t know—what they couldn’t know until prosecutors at the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division plumbed deeper into his files—was that Syring had accumulated a fairly significant rap sheet by the time he placed his first call to Zogby. Syring, it turned out, had a history of terrorizing certain foreigners—a pattern that seems to have raised few red flags at State.

Zogby knew Syring wasn’t his fault, but he still felt guilty: “Why am I inflicting this on everyone around me?”

According to memos written by his defense attorneys, Syring’s anti-Arab sentiments took hold during two stints in Beirut in the 1990s. Then came 9/11. Syring, posted to the US consulate in Frankfurt, became concerned that he had granted a visa to one of the hijackers who flew to the US via Germany. He scoured the visa files and found nothing to support his hunch. Even so, the preoccupation appears to have festered: In 2002, he began circling “country of birth” and writing the letter T–for “terrorist”–on applications from people of Middle Eastern descent. The same year, according to a filing by prosecutors, Syring returned two applications by mail with terrorist written on the envelope.

Syring’s superiors confronted him, but instead of stopping, he doubled down. According to the prosecutors’ filing, he told a supervisor that “applicants supported terrorism solely by virtue of the fact that they were citizens of certain countries.” And off the clock, in one of his first known instances of trolling people from a personal account, he emailed a German bank that had loaned money to Iranians to say it should “burn in hell for eternity.”

At some point between 2002 and 2003 (official records offer conflicting accounts), State finally booted Syring from the consulate. Yet he was allowed to take what’s known as voluntary curtailment—i.e., return to Foggy Bottom for a desk job, with no apparent disciplinary implications. (A spokesperson for State declined to discuss Syring’s career.)

And incredibly, in June 2006, according to one of his lawyers’ filings, State bestowed on Syring an award for “special and outstanding service.”

Just a month later, he made his first call to the AAI offices.

Having confessed to Bristol, Syring was arrested in the summer of 2008. He was released on his own recognizance and promised the judge he’d stay away from all AAI employees and the office. A few weeks beforehand, State had quietly allowed him to retire. (He was apparently allowed to collect his pension at least up until 2019, according to his lawyers that year.)

The episode barely registered on Washington’s radar—it was August in the middle of a presidential campaign. “Let me just underline the seriousness with which the secretary approaches the idea that the State Department should be a workplace that in no way, shape, or form tolerates discrimination or hateful language or any other action that would violate federal laws or regulations,” Sean McCormack, a State spokesman, said at the time.

Syring was charged with two counts, for sending threats via interstate commerce and for violating Zogby’s and his staff’s right to work in safety regardless of their ethnicity. The latter charge—a crime of hate—hinged on Syring’s threat of violence: “The only good Arab is a dead Arab.”

Syring’s team negotiated a deal: He pleaded guilty to the hate-crime charge, a misdemeanor, in exchange for a year’s probation and no jail time. As far as anyone knew, it was over.

And then it wasn’t. Syring escalated his attacks, the same way he had after being reprimanded in Frankfurt. In a baffling, self-destructive blitz of emails, he blasted LinkTV, a network where Zogby hosted a show, with a repeat of his “only good Arab” threat, and sent screeds to DOJ lawyers—the very bureaucrats with power over his case.

The plea deal fell apart. Syring was arrested and jailed, and the count for sending threats via interstate commerce—a felony—was reinstated.

In the summer of 2008, he was finally sentenced, two years after his initial calls to Zogby. The hearing was the first time Zogby and his colleagues saw him in the flesh: a tall, balding, flush-faced man in an orange jumpsuit. “I realize how much my actions and my words have affected Dr. Zogby and so many other people,” Syring told the judge, speaking rapidly from his prepared statement. He promised never to repeat his behavior.

The judge sentenced Syring to a year in prison and three years of supervised release. This was the last, Zogby thought, that he would hear from “Patrick from Arlington.”

And it is true that during the next four years, as Syring sat in jail and then supervised release, Zogby didn’t hear from him.

Others weren’t so lucky. Syring was hewing to the terms of his release: attending anger-management classes and therapy sessions, completing his community-service landscaping work, doing “a very nice job,” according to the judge. He was, of course, forbidden to contact Zogby. But the initial terms didn’t strictly bar him from contacting people in Zogby’s orbit. And beginning in 2009, he sent dozens of emails to anyone who might have a connection: Arab-American academics, employees of other advocacy groups, AAI’s corporate sponsors, and on and on.

Watching Syring dig through his personal Rolodex, Zogby felt overwhelmed and helpless. After experiencing racism throughout his career, he wasn’t convinced everyone would dismiss Syring’s attacks. He knew how easy stereotypes could stick. “You’re the ‘Arab guy,’ ” he says. “And then you achieve a modicum of success and there’s someone out there writing, ‘This is a terrorist.’ You don’t know how people are taking it.” Haunted by the prospect that people might actually believe Syring’s claims, or at least decide AAI was too much of a liability to work with, Zogby asked his staff to see which of his associates had heard from Syring. Who else might have been told he was a terrorist? Who might, privately, have found that theory somewhat convincing?

Prosecutors pleaded with the judge to extend Syring’s probation, saying he was “conniving” and “manipulative” and “has made every effort to avoid and get around [the court’s] orders.”But according to experts, he was sane. Mental-health evaluations commissioned by the court repeatedly concluded not only that he had no obvious mental-health problems but that he didn’t present a physical threat to anyone. The judge dismissed the government’s entreaties. Syring’s probation ended in January 2012. As far as the law was concerned, he could call whomever he wanted. And now Syring had time on his hands.

Early that year, after passive-aggressively forwarding Zogby the Washington Free Beacon story, Syring launched a fusillade of new hate mail on AAI’s staff: once a week, four times, ten. As the year passed and the bloody aftermath of the Arab Spring consumed the Middle East, he had plenty of material: a court dispute involving “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh, the death of Ambassador Chris Stevens in Benghazi, the tangential involvement of a Lebanese American, Jill Kelley, in the downfall of General David Petraeus. Officials began keeping a list on a yellow legal pad of all the acts for which Syring blamed Zogby, a tally that astonished Zogby when he eventually saw it.

Zogby often commuted home to Virginia with his daughter Sarah, and she could always tell when he’d gotten a Patrick email. Like many DC nonprofits, the Arab American Institute is staffed mostly by mission-driven twentysomethings. The organization inspires an outsize level of loyalty—many employees described it to me as a “family,” with Zogby, a father of five, a benevolent and inspiring grandfather figure. Besides his fear for his wife and children, he felt an enormous responsibility toward his work family, who were feeling the effects of Syring’s hate themselves. Interns had to be briefed on the situation. It became a rite of passage for new employees: Your bio went up on the AAI site, a Patrick email popped up in your inbox.

“These kids . . . came here to get a Washington experience,” Zogby says. “This is not the experience they bargained for.” He knew Syring wasn’t his fault, but he still felt guilty sometimes: “Why am I inflicting this on everyone around me?”

Just as he had boasted to Bristol, Syring was intimidating them—the messages adhering to a banal rhythm (Arab Americans are genocidal murderers, all Arab Americans are complicit)—yet he was carefully avoiding threats of harm. Unlike vows to kill or maim, vulgar racist messages are protected by the Constitution. Syring appeared to have an expert grasp of the distinction and seemed to relish flirting with it, once forwarding an article that used the words he’d been locked up for—“The only good Arab . . .”—but never using them himself.

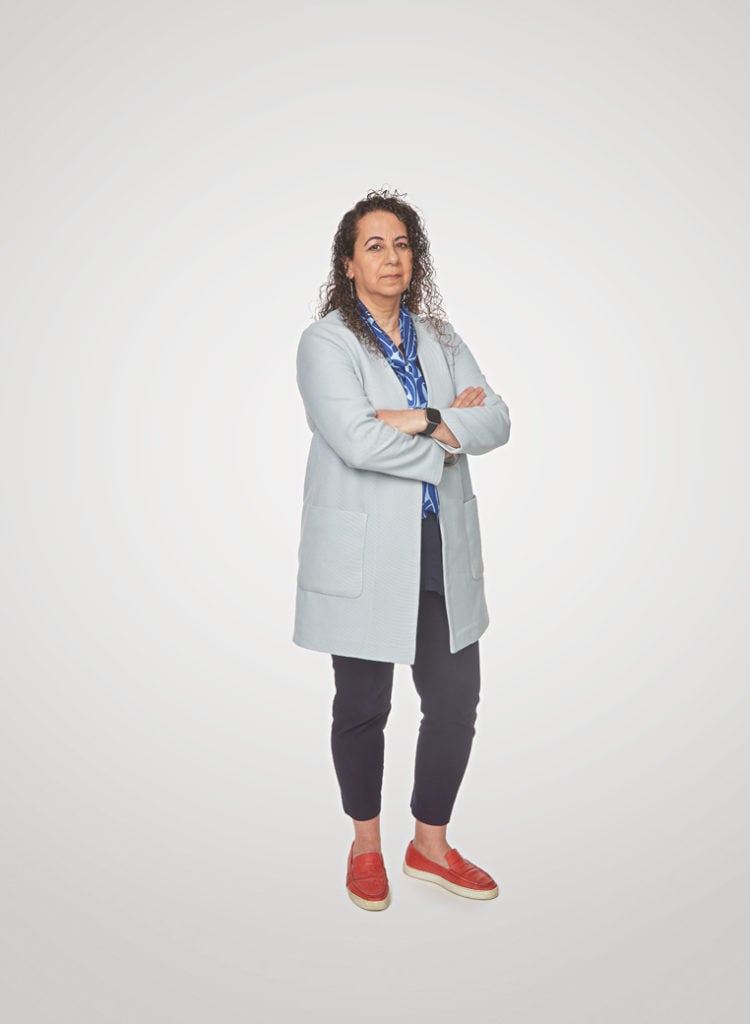

Staffers were frustrated. Maya Berry, who became the institute’s executive director in 2011, said they would dutifully forward Syring’s messages to the FBI “and we would hear nothing.” The limits of the law were maddening, while the limits of his capabilities were a gruesome conundrum: Was he just a despicable troll? Or a mass shooter lying in wait? And how would you know before it was too late? Their boss was a Washington figure with tremendous clout, a guy who had relationships with presidents and who had held a meeting with Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice shortly after her employee began sending hate mail. Yet in this particular instance, Zogby’s noxious, persistent troll held more power than he did.

Zogby wasn’t Syring’s only target by a long shot, but most of his other targets were in Zogby’s world, many of them Arab American themselves. His vitriolic interests also ranged. For instance, he carried on a years-long, hate-filled correspondence with a Washington Blade columnist, Richard Rosendall, about things like abortion. And he was also trolling the lead prosecutor on his case, Mark Blumberg.

Hoping to build a new case, Keith Palli, the FBI agent who took over the case after Bristol retired, got a warrant to search Syring’s condo in late 2014. The home, as Palli remembers it, was one of the cleanest he’d ever searched—both in the sense of not containing anything incriminating and also just plain clean. Piles of books and newspapers were everywhere, but it was all orderly—including the bedroom closet containing his large collection of legal documents. Palli noted a wine rack, a small porn collection, souvenirs from abroad—just the modest home of an older man who lived alone and spent most of his time riding his bike, traveling, and going to the gym. There was no sign that Syring posed a physical threat—no firearms, no floor plan of the AAI offices, no written-out plans of attack.

After the search, Syring was quiet for a month. But early in the new year, he was hitting AAI with new messages nearly every day. It was as if the FBI’s slap on the wrist had only encouraged him. “The longer that he would go and no one would bother him, he would start to get more and more emboldened,” says Palli. “Almost like he wanted . . . a reaction.”

On June 12, 2016, an Afghan American man shot and killed 49 people at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando. It had been almost exactly ten years since Syring materialized in Zogby’s life. Hearing the news, Zogby had no time to mourn—instead, he braced himself for what was coming.

“I, and all LGBT Americans, will not be intimidated by America’s monster terrorists,” Syring wrote in a screed that soon hit Zogby’s inbox. “James Zogby and all Arab Americans, are homophobic monsters who murdered 49 LGBT Americans.”

It was a hard summer. Donald Trump’s presidential campaign was taking flight, ratcheting up ethnic tensions across America. It seemed entirely plausible that someone like Syring might decide it was time to take matters into his own hands and eliminate the “monsters” himself.

Berry’s office shares a wall with the elevator bank, and every time she was there late, the “ping” of the doors opening gave her a start. When they left for the night, staffers would check over their shoulders. For years, Zogby’s wife, Eileen, stowed a picture of Syring at home, just in case. Junior employees kept their own copy in their phones. “Is this knowledge I want to have?” Heba Mohammad, then the institute’s national field coordinator, remembers thinking. “Because every 60-year-old man with a bald head . . . am I going to think it’s him?”

Zogby and Berry asked the Department of Homeland Security for a walk-through of the offices to assess for vulnerabilities. The exercise was the opposite of reassuring. AAI occupies about half the sixth floor of its K Street building. Coming out of the elevators, you turn right for Zogby’s office or left for the main office, where most employees sit behind a large glass wall in open-plan desks. There’s no exit besides the glass door in that wall. If someone came out of the elevators with an assault rifle, he’d be able to kill most of the staff in seconds.

The building added some new security measures, but it was clear that a worst-case scenario would not be preventable. AAI staffers began some grim preparations. Berry kept in a drawer the DHS checklist for how to respond to an attack and read it when she felt anxious. Zogby visualized an assault so clearly that he could picture the color of Syring’s gun—in his mind, always silver. Margaret Lowry, who was then the institute’s special-projects manager, mentally rehearsed rushing the interns and the staffers with children into a back room. “All it takes is one thing for it to be the day that Patrick wakes up and decides today’s the day,” she remembers thinking.

After Trump’s election, Syring’s invective felt more threatening. He was clearly emboldened by the new administration. Yet although he continued to creep up to the line, he didn’t cross it.

Then, suddenly, he slipped. On May 30, 2017, just before the first anniversary of the Pulse shooting, he wrote to Zogby and several colleagues that “James Zogby is a devil. . . . LGBT Americans will never be safe until we cleanse America of Zogby and his evil, filthy, vile, despicable, abhorrent LGBT-hating Arab American monsters.”

On June 12: “Death to all Arab Americans.”

And an hour later: “We will never forget. We will never forgive: James Zogby’s Orlando genocide: Orlando June 12, 2016. The only good Arab American is a dead Arab American.”

It was the same—unlawful—threat Syring had issued against AAI in 2006 and had promised never to repeat.

For the second time in roughly a decade, a grand jury recommended an indictment. Prosecutors charged Syring with hate crimes and unlawful threats against seven AAI employees. Once again, he was not initially detained. And once again, he returned to his keyboard, forbidden to contact Zogby and his colleagues, but this time spraying members of the Arlington County Board. In early 2019, ahead of trial, the judge finally ordered him locked up.

With Syring behind bars at least temporarily, Zogby and his colleagues enjoyed a nearly forgotten sense of normalcy. But they cycled through waves of anger and confusion, too. Syring had blitzed them with some 700 hate-filled emails over five years–without any consequences, until now. He’d caused PTSD-like symptoms in some of them: Berry began to feel anxious in crowds; Lowry, who had started law school, always sat at the end of the row in lectures for an easy escape; several began to feel sick in the morning while checking their inboxes.

“Is he brooding? Is he plotting? Is he thinking dark thoughts?”

Even Palli, the FBI agent, told me that despite knowing for years that the bureau didn’t yet have enough evidence for a case, he found Syring “scary” and worried about the AAI employees. How could so many experts have concluded that Syring wouldn’t hurt them when his victims felt with such a visceral certainty that he would?

Part of it, at least for some people involved in the case, was that Syring just didn’t seem the type—white, older, someone who’d spent decades in a cautious bureaucracy. It didn’t make sense that a man with so much to lose would operate at such a high personal cost. Bristol had initially hedged his investigation for this reason, believing that a midlevel State Department employee probably wouldn’t also be a racist troll. (He says he would never make that assumption now.) Some people even came away with a favorable, or at least neutral, impression. As the judge who had presided over his first case said at his sentencing hearing in 2008, “Mr. Syring strikes me . . . as intelligent, well spoken, well educated.” After his second arrest, in 2017, Syring was initially allowed to walk free.

“From the prospective [sic] of his attorneys,” his lawyers wrote in a 2019 sentencing memo, “to the likely disbelief of the prosecution, court, victims and perhaps public, Mr. Syring is kind, considerate, thoughtful and anything but confrontational” (their emphasis, presumably added to discount the idea that he might ever drift from murderous language to murderous behavior).

But for AAI employees, the notion that Syring’s persona was at odds with his actions ignored the reality of hatred. Mostly Arab American themselves, they have lifetimes of experience with people who “wouldn’t harm a fly,” as one neighbor described Syring. How might the case have played out, they and others wondered, if Syring were Arab American and his targets were a group of politically connected white professionals?

A central part of Syring’s defense was the repeated assessments by mental-health professionals that he didn’t pose a physical risk. Forensic risk assessors rely on two methods: their own professional judgment and actuarial data correlating certain behaviors or history with commission of a violent crime. Syring had almost none of the known red flags for a major attack. He had no history of violence and no previous criminal record. He had a steady job and a relatively stable personal life. In all his time harassing AAI’s staff, he never crossed a physical threshold such as showing up at someone’s home. All of these facts bolstered, for years, the argument that Syring’s emails didn’t amount to a true threat.

Yet when it comes to evaluating that specific risk, it’s not clear that data gathered prior to the rise of cyberstalking is even useful, says Paul Elizondo, a forensic psychiatrist at the University of California, San Francisco, who has studied cyberbullying extensively: “Right now it’s just a very poorly understood area, because this is very much new behavior within the last three decades.”

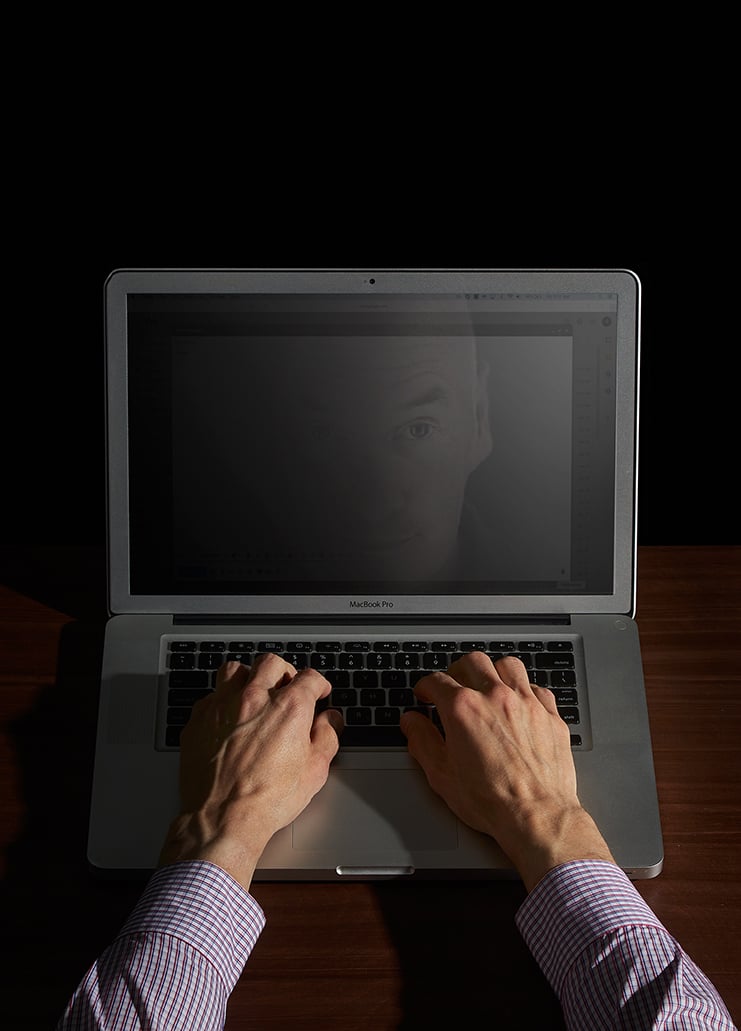

Did the legal system’s inability to quickly squelch Syring put Zogby and his organization in danger? In the end, his actions fell into a space of unknown unknowns, where nearly everyone involved saw risk and yet no one felt they had the right information to act. Zogby and his colleagues lived in that blank space for what seemed like an eternity. But they were hurt as surely as if Syring had physically attacked them. He didn’t have to pick up a gun to do it. He merely had to turn on his laptop and type.

Syring’s trial was held in DC in May 2019, and the jury convicted him on all counts. Zogby reached his hand back over his seat to hold Berry’s as they listened to the fourteen “guiltys,” and she saw he was crying. “Seeing Jim break down like that,” she recalls, “that’s like seeing my father break down.”

Syring was sentenced to five years in prison and three years of supervised release. Manacled and, according to his lawyers, more than 40 pounds lighter since his incarceration, Syring sat stonily at his table during the hearing, barely raising his head.

With their abuser behind bars, AAI employees are now free from the corrosive fear that once defined their lives. Berry used to tremble every time Zogby went to smoke his daily cigar at a local restaurant where the owner always saved him an outside table. After the sentencing, she could go out and sit with him without checking around both corners for Syring. Lowry finally broke her old nervous habits of sitting by the library exits and at the end of the row in lecture halls.

But, as AAI development director Jennifer Salan puts it, the dominant feeling is one of “dread delayed.” This time, no one at AAI believes that Syring’s sentence, long as it is, will deter him as soon as he’s free to menace them again. Syring still owns his condo in Arlington. His black Honda Fit is still parked in its spot outside, with a bottle of hand sanitizer tucked up front and a neat stack of maps behind the passenger’s seat, awaiting his return.

For a while, Zogby thought about Syring relatively little. Just months after the sentencing, Eileen, his wife of 51 years, suffered a stroke. She died on March 11, 2020, days before the entire country shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic. Isolated from his large and loving family, Zogby grieved alone. “[Syring] was the last thing on my mind,” he says.

Yet as time has passed, Syring sometimes creeps into his thoughts. “Is he brooding?” Zogby wonders. “Is he plotting? Is he thinking dark thoughts? Is he getting help? Does he understand now, finally, that what he did was wrong?”

Zogby will be 78 when Syring gets out of prison, if he serves his full sentence, and 81 when his probation ends. If Syring reappears in Zogby’s life at that point, it will mark 20 years and counting that his obsession has persisted—20 years in which Zogby has never fully understood what Syring might be capable of doing to him. “I didn’t know, I never knew,” he told me recently. “And I still don’t know.”

This article appears in the June 2021 issue.