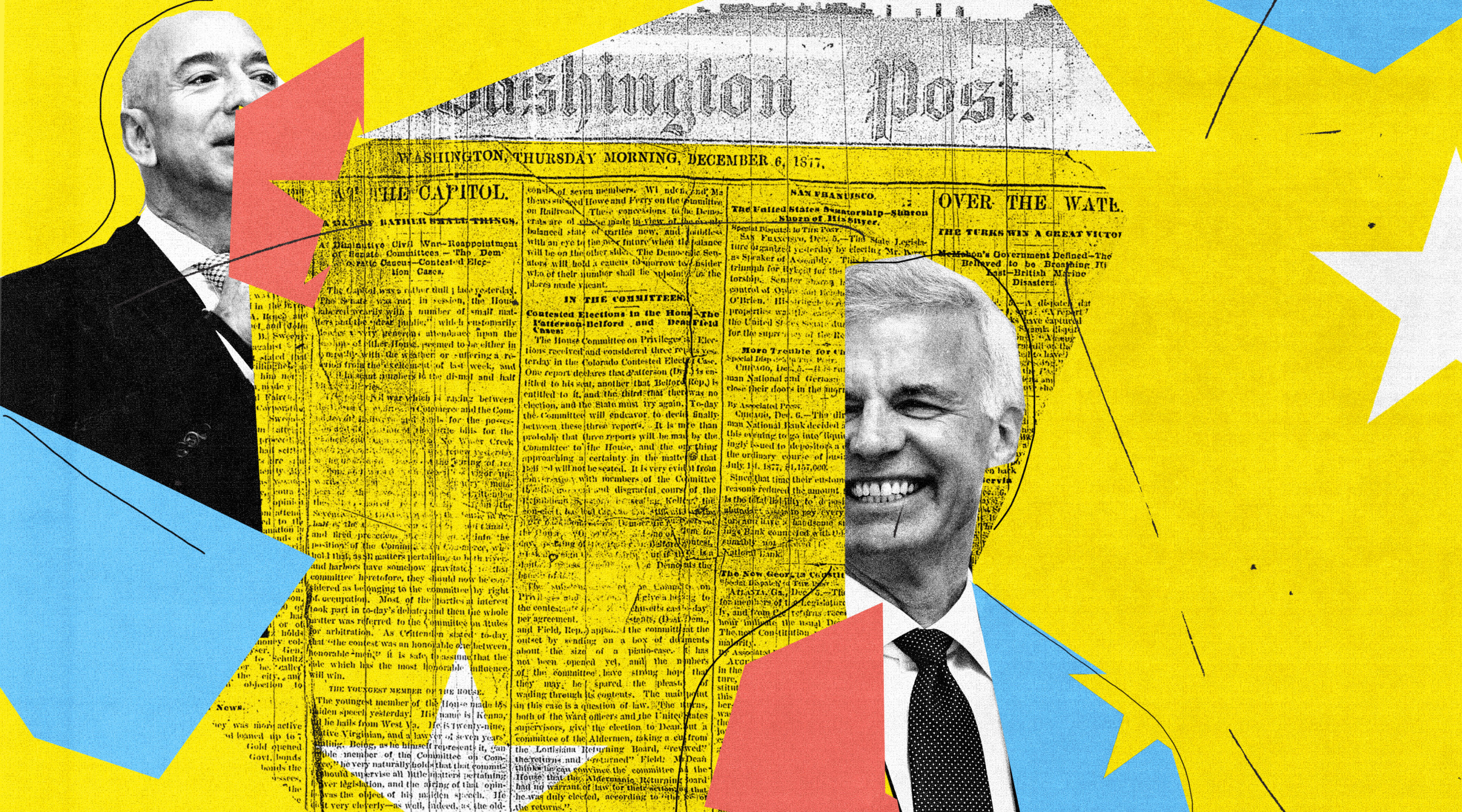

The last round of the tryouts took place over four meals this past spring at Jeff Bezos’s Washington home. Each guest of honor was a contender to become the new executive editor of the Washington Post, and their invitation to Bezos’s $23-million Kalorama mansion included a guest. They supped with Bezos and his partner, TV personality and producer Lauren Sanchez; the paper’s publisher, Fred Ryan; and his wife, Genevieve McSweeney Ryan, dining off dishes emblazoned with the Post logo and taking questions from the world’s richest man about how they might run his newspaper. The plates weren’t the only piece of Post swag Bezos showed off—according to two sources, he also told guests he owns a lock busted by the Watergate burglars.

Almost nothing about the setting—or the paper’s circumstances—resembled the last time the Post had gone shopping for a new editor. In 2013, when Bezos paid the Graham family $250 million for the paper, it was bleeding money. Marty Baron, a laser-focused editor with a reputation for steering hard-hitting city coverage while pinching pennies, had been tapped by the Grahams to winnow ambitions as the business model collapsed.

But then Bezos arrived. He poured rocket fuel on Baron’s latent ambitions—investing millions to nearly double the Post’s ranks, blow out its technical capabilities, and supersize the editorial vision. The big idea, as Baron once described it: “Why are we taking all of the pain of the internet and not taking the gift that the internet had to offer?” Over the next eight years, the Post transformed itself from a dwindling hometown broadsheet to a national media company with a ballooning readership; profitability; ten Pulitzer Prizes; and more than a little swagger. Now, in a Kalorama mansion grander even than Katharine Graham’s former salon, the Post’s billionaire owner and his publisher were choosing the first editor of their era.

By this point, the guest list for the dinners had been narrowed via Zoom calls with dozens of people, in-person interviews between Ryan and the first cut, and strategy memos from the most interesting candidates. Bezos and Ryan talked with four finalists before the boss extended them invitations to dinner. Two were internal: longtime managing editor Cameron Barr and Steven Ginsberg, who edits the national section. The other two were women leading other newsrooms: Meredith Artley, editor in chief of CNN Digital Worldwide, and Sally Buzbee, executive editor of the Associated Press.

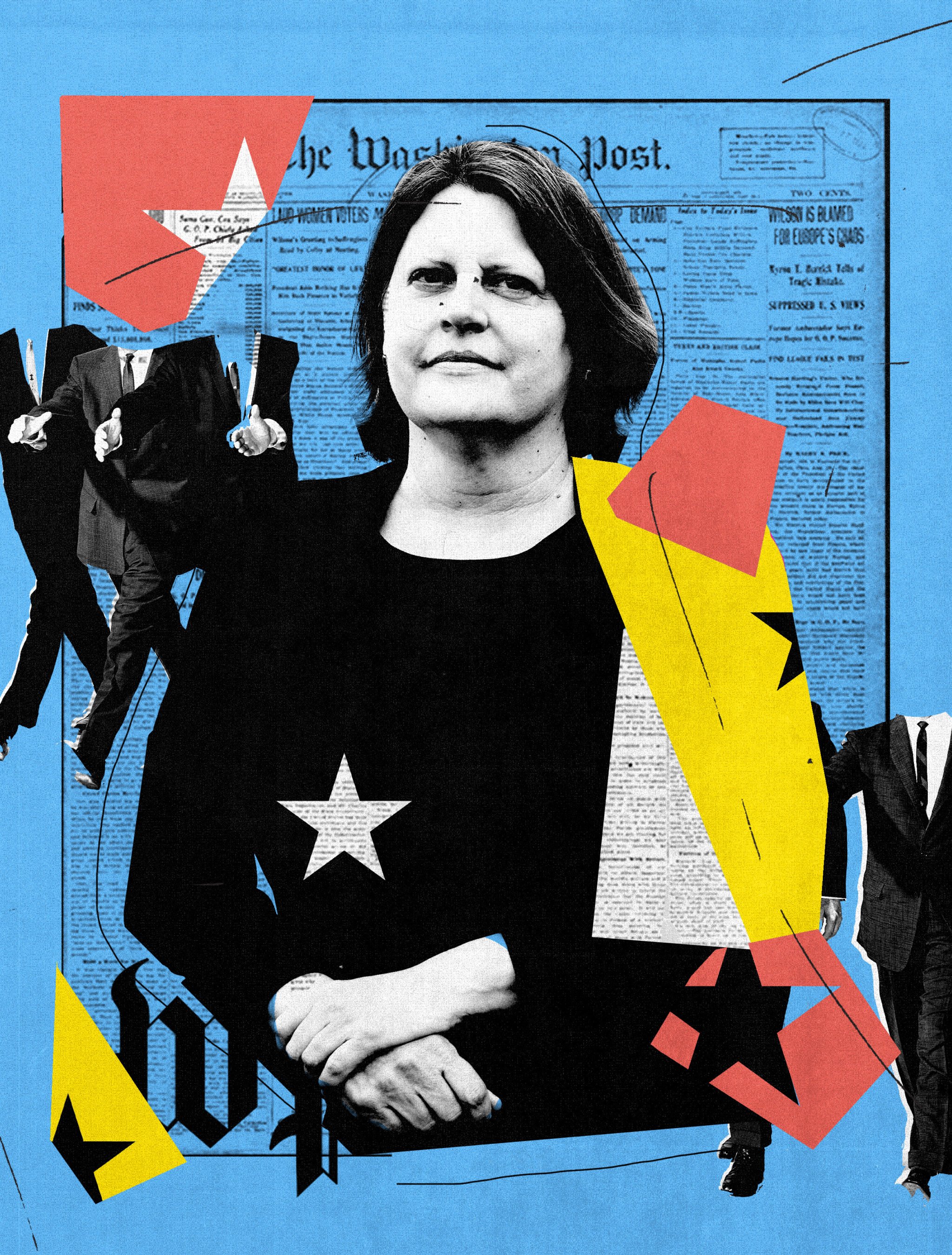

On May 11, Ryan announced that Buzbee—whose AP career included deep-bench experience in DC—had the job. And on June 1, she became the first woman to top the masthead at the 143-year-old paper. “You know, the Post has been fortunate to have some exceptional editors in Ben Bradlee and Marty Baron, and I think Sally is of that ilk,” Ryan says, explaining that he and Bezos left the dinners aligned in their selection. “I was really pleased that we both felt, 100 percent, Sally was the right choice.”

Buzbee inherits a paper with an audience of 80 million to 100 million per month and a newsroom that has mushroomed from fewer than 600 people to roughly 1,000. She has to navigate a charged political environment in which one half of the United States views the Post as a tool of an elite plot to overthrow democracy while the other half views the same people as a vital bulwark against totalitarianism. And she answers to a boss with extremely grand ambitions. The thinking that led to the hiring of Buzbee—leader of an outfit with little of the iconoclasm or romance of the old Post but a global presence that no single newspaper has ever managed—offers a peek at just what those ambitions are.

Yes, Buzbee’s mandate demands more marrying of technology and journalism—the ratio of journalists to engineers at the Post is now 2 to 1. But it also necessitates a new sort of expansion, one that involves not only the budget but the very concept of just what an American newspaper’s audience should be. “We want to grow,” says Ryan. “We want to grow domestically in terms of our readership across the country, and we want to grow globally with international readers. A lot of our strategy revolves around that.” After setting out to build the world’s largest online store, Jeff Bezos now wants to turn the Post into the newspaper for the world.

Buzbee’s arrival in Washington is a homecoming of sorts. During the six years she headed AP’s Washington bureau, she lived in Tenleytown with her husband, John, a Foreign Service officer, and their two daughters, who graduated from Wilson High School. One of their children died as an infant, and John died from cancer complications at the age of 50 in September 2016. It was only a few months later that Buzbee landed AP’s top job.

By then, she had spent her entire career with the company. After graduating from the University of Kansas, Buzbee reported for AP from Topeka, did a stint in the DC bureau, then became Middle East editor in 2004, running operations from Cairo. Six years later, she was named chief of the Washington bureau, overseeing much of its US political coverage as well as its storied investigations team. Over her three decades in the business, Buzbee, who’s 56, cultivated a reputation as a monk-class journo nerd (“I love journalism so much, I can’t stand it,” she told the New York Times this spring), an image that aligns neatly with the newswire that shaped her.

“I would have conversations with her to say, ‘Listen, we should publish this story, but there’s going to be blowback. They’re going to freeze out our reporter.’ Every time, she was like, ‘I get it, but this is important and it’s worth the freeze-out.’ ”

AP is known for rigorous reporting and unflashy writing, and its stylebook is a journalism bible—there are people still furious about its 2014 decision allowing “over” as well as “more than” when describing a quantity. Its work is carried globally by media outlets, yet the institution is a mostly invisible force. Not long ago, the leader of a newswire wouldn’t even have received a polite “thanks but no thanks” from a major newspaper with a special self-regard that dates back to Watergate.

Buzbee’s résumé, though, has bullet points that would catch the eye of Ryan and Bezos. She has an MBA from Georgetown. She has experience running a big, worldwide organization: AP reportedly has 3,000 employees, three times the Post’s. And she stood up AP’s so-called Nerve Center, which changed how the company distributed content to members around the world.

The center is a high-metabolism, multi-pronged news hub, a complex digital operation designed to keep AP nimble and competitive with other news organizations—monitoring social media, directing AP’s considerable resources to breaking stories, promoting its articles on social platforms—experience that would translate directly to a multifarious organization like the Post. Indeed, Ryan wrote in a memo to the newsroom, that role “helped shape her ambitious vision for the Post’s digital future.”

But the news was a big surprise to staffers who’d been reading the tea leaves—and, even amid the historic nature of the hire, it sparked a wave of sore feelings.

The hands-down staff favorite had been Kevin Merida, a beloved former managing editor who spent nearly 23 years at the Post before leaving for ESPN’s The Undefeated. Recruiting him back would have made him the paper’s first Black editor. For many insiders, that would have been redemption for an employer that has struggled to retain staffers of color, who according to a 2019 report from the Post’s union, make about 15 percent less than their white counterparts. One journalist I spoke with equated the hopes of a Merida comeback to Democrats in the Trump years pining for President Obama.

Yet Merida didn’t even come close to scoring a dinner invite from Bezos. Friends say that rather than courting him, the Post belatedly asked Merida to put himself forward. ESPN and the Los Angeles Times, meanwhile, were wooing him aggressively at the same time, and the LAT named him executive editor on May 3, a week before the Post heralded Buzbee’s hiring. (Merida declined to comment.)

Others were disappointed it wasn’t Ginsberg, the national editor. A Post lifer at 49, he’d worked his way up from copy aide to handling the organization’s most visible coverage, steering many of the articles on Trump Town that shocked people awake via push alerts on their phones. His team bagged half of the Post’s Baron-era Pulitzers. But he’d also never run a publication, and his appointment might have signaled that the Post was content to be known as a politics paper. (Ginsberg declined to comment.)

A widespread theory among some who felt unconsidered in the search process or disappointed in its result is that Buzbee hadn’t pined for the job until Ryan recruited her into the bake-off. The thinking goes that Baron, who preceded both Ryan and Bezos at the paper, never had a clear incentive to listen to Ryan, and by shepherding Buzbee’s candidacy, Ryan not only would be known for a first, but he’d finally have an executive editor who owed him. Ryan allows that the search did involve “very aggressive outreach” but declines to get into specifics about the process.

At any rate, it’s not all that surprising that Bezos didn’t appoint from within. Unlike the New York Times, which almost openly cultivates potential heirs apparent, recent Post editors have been newcomers. Plus, Ginsberg and 57-year-old managing editor Cameron Barr, the other internal contender, would have ascended with baggage. Both are middle-aged white men who made their bones in a newsroom where almost every major desk is headed by a man, and none of the three women with the title of managing editor got a serious look. (Barr didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

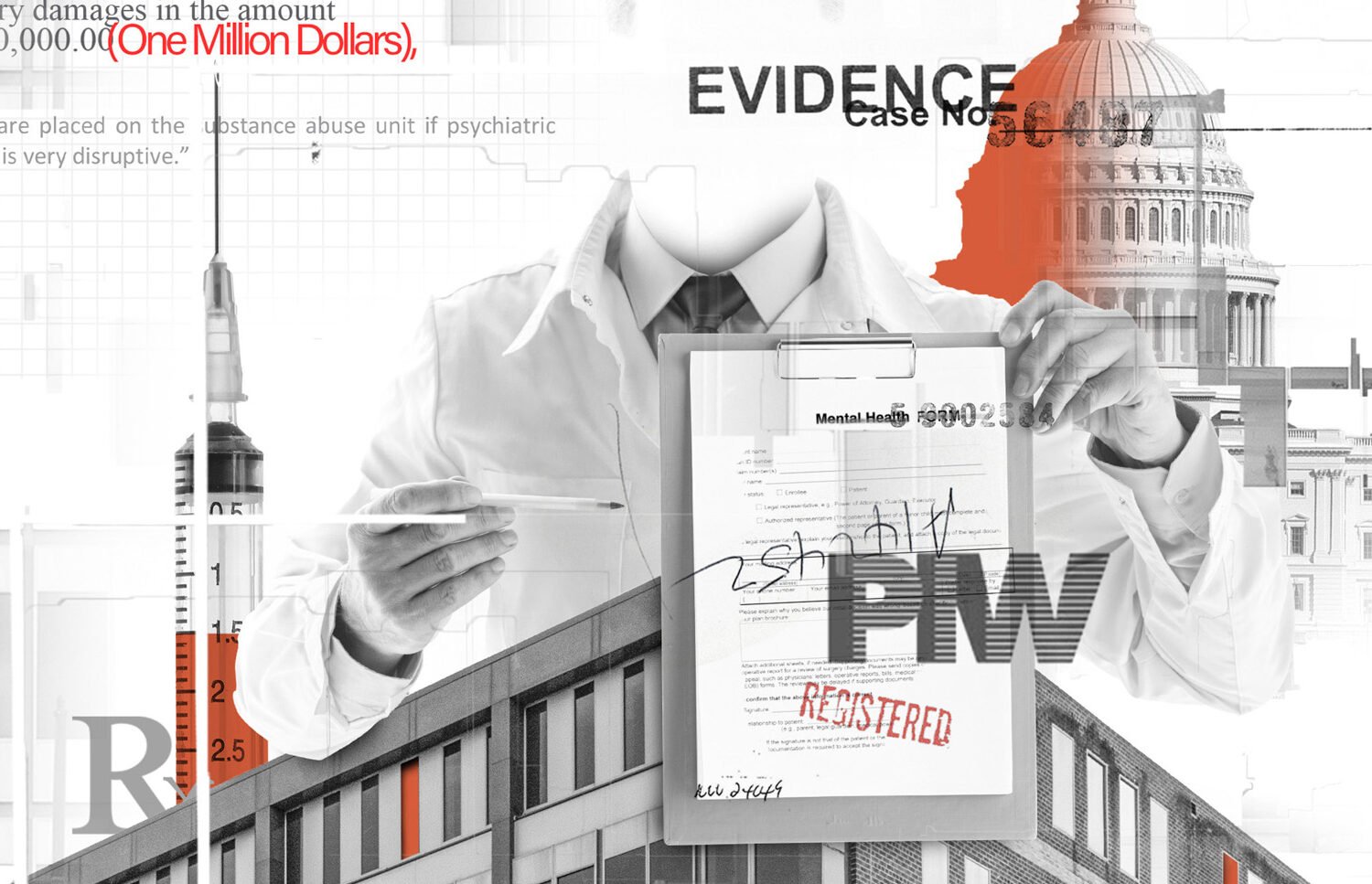

Barr and Ginsberg were also in the chain of command during a #MeToo-era debacle that continues to unsettle the newsroom. It blew up after the brass suspended reporter Felicia Sonmez for tweeting an article about Kobe Bryant settling a sexual-assault lawsuit. (The tweet came hours after Bryant’s death; Baron said Sonmez was “hurting” the paper.) She later revealed that her bosses had banned her from writing any article that touched on #MeToo because she had identified herself as a victim of sexual assault. An outcry over her treatment put the Post in unflattering media-world headlines, and the drama, now in year two, has yet to go away: In July, she sued.

The final candidate—Artley, the CNN honcho—doesn’t seem to have been on the radar of anyone who tried to divine Bezos and Ryan’s search. But it’s easy to see why a tech-mogul owner would have been intrigued by an Artley candidacy. At 47, she was the youngest finalist and has sterling credentials in digital news—working on the Times’ early efforts online, overseeing the influential Online News Association, and running a news site whose traffic dwarfs the Post’s. Of course, her hiring would likely have raised hackles among newsroom types, who like to look down on TV types. Ironically, she was also the only person for whom the job would arguably have been a step down. Why help build a media brand’s global aspirations when you’re already running one known as well in Karachi as in Kalamazoo? (Artley didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

That left Buzbee. When she oversaw AP’s investigations team in Washington, it broke big stories. In 2015, it revealed that Hillary Clinton had kept her private email server in her New York home and, in 2016, that Paul Manafort had helped secretly direct millions of Ukrainian dollars to Washington lobbying firms. “Sally had our back on some really tough stories,” says Ted Bridis, who edited the desk under Buzbee. “I would have conversations with her to say, ‘Listen, we should publish this story, but there’s going to be blowback. They’re going to freeze out our reporter and not return our phone calls, and you have to be prepared for us to not be competitive on this beat until the relationship thaws.’ Every time, she was like, ‘I get it, but this is an important story and it’s worth the freeze-out.’ ”

Bridis, who worked with Buzbee for more than a decade, says she was an editor who could wrestle a thorny article to the ground in a matter of hours and a boss adept at absorbing flak from the government bigwigs subject to AP’s scrutiny. She excelled at marshaling as much of the organization’s investigative “firepower” as possible when big stories beckoned.

Something else: She held an increasingly quaint view about objectivity, frequently invoking the idea that AP had to be like Caesar’s proverbial wife. “ ‘We have to be above reproach,’ ” Bridis says. “I think it was a catechism that she lived by.”

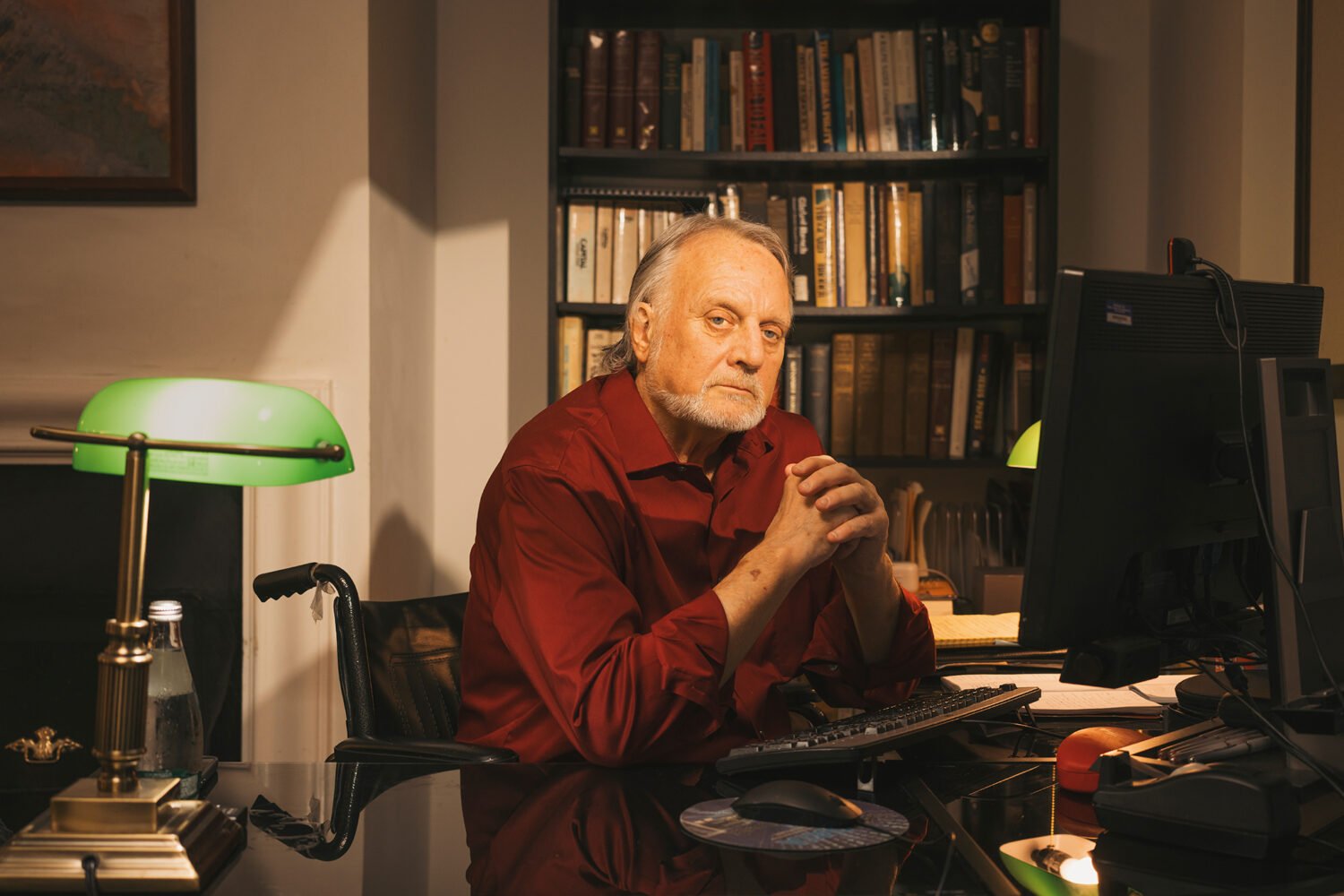

Buzbee’s appointment is an important first, but it’s also a career-defining flex for Fred Ryan, the publisher Bezos tapped to turn the Post profitable. A onetime aide to Ronald Reagan, Ryan migrated into media in the ’90s, becoming president of Allbritton Communications, which owned WJLA (Channel 7) and seven other TV stations. In 2007, he was named CEO of the Allbritton digital offshoot that would come to upend the DC media business with its agile, aggressive political coverage: Politico.

To Bezos, Ryan was a valuable insider, a bedrock member of Washington’s elite-iest elites but also someone with a record of making disrupters and the establishment feel comfortable with one another. At Politico, he had been responsible for landing the type of huge corporate sponsorships that helped turn Allbritton’s big bet on digital news into a moneymaking enterprise, and he muscled the scrappy outlet into the top tier by arranging for it to host presidential debates at a time when big news-breaking online was still a novelty.

The Post was the opposite of scrappy when Ryan arrived in 2014. It had a new paywall but no digital-subscription team. Bezos, who had some experience converting people from browsers to subscribers, opened the spigot so the company could build out the tech infrastructure that would enable greater volumes of content and the pipelines for transporting it into readers’ feeds. Engineers and data scientists joined the newsroom, while a tech chief and managing editors who were focused on digital products oversaw an effort to make the Post ubiquitous.

Having Bezos had its perks: Amazon Prime members got free six-month subscriptions, and the Post app got nice placement on new Kindle Fire tablets. But other experiments attempted to guide people from being readers of, say, health articles to paying patrons by keeping track of what they read and showing them offers before they hit their article limit. Digital-only subscriptions began to rise by eye-raising multiples: 145 percent year over year from 2015 to 2016, for instance.

The Silicon Valley–style mandate became iterate, iterate, iterate. “This is one of the great benefits of Jeff Bezos owning the Washington Post,” Ryan says. “You can have great journalism. But if you cannot get it out to the way people are consuming today and tomorrow, that journalism is not having the impact it could have.” Bezos, he says, does a call every two weeks with product teams: “They’ll go through the flow of perhaps a new subscription process to see how that works, or a new product that will help our site load faster or be more engaging, more riveting, in the storytelling.”

Eight years later, the Post has gone from 35,000 digital subscribers to 3 million, while its average Sunday print circulation has dropped by 46 percent, to 335,000, according to the most recent figures from the Alliance for Audited Media. And the paper that described itself as “For and About Washington” when Bezos bought it now collects 95 percent of its digital traffic from outside the DC area. Last year was its biggest ever for digital advertising, Ryan says, and it’s on track to beat that in 2021. Its events business also boomed unexpectedly in 2020, as the Post spun up virtual sessions with newsmakers; it now plans to make the events permanent. The company collects revenue from developing digital tools as well. It built its own content-management system, for instance, which it also sells to other publishers and corporate entities such as BP. (As a private company, the Post doesn’t share specifics about its business.)

But to meet the ambitions of the owner, the Post has to worm into way more than Fire tablets. The price of digital ads depends on the number of people reading. And while the company made startling gains during the Trump years—more than 100,000 people, a Post record, viewed David Fahrenthold’s Access Hollywood article simultaneously when it went live in October 2016—the Post’s US traffic in the first six months under the comparatively boring Joe Biden tumbled, just as it has at other top news outfits: It had almost 28 percent fewer unique readers in June 2021 (73.7 million) than in June 2020 (101.6 million).

So what do you do when the goose that laid the golden egg moves to Mar-a-Lago? One tack involves messaging. During the Trump era, while the New York Times and CNN made TV ads positioning themselves as homes to truth and facts, the Post’s branding efforts were mostly limited to slapping Bezos’s “Democracy Dies in Darkness” slogan on the masthead. This July, though, the Post announced it was establishing a chief-subscriptions-officer job to convert more readers into subscribers and installing Michael Ribero, a veteran of Sling TV and Paramount+, in the gig.

But the new Big Idea is taking shape on the editorial side: turning the Post into a go-to for global readers.

The company has spent the last few years beefing up in subject areas that transcend borders. The staff on the business desk grew by more than 50 percent, to up the focus on tech—the business, its intersection with Washington, and its place in consumers’ lives. The Post built a gender-focused vertical called The Lily, a digital play for millennial women readers. Its opinions side, which accounts for a significant amount of web traffic, started a popular franchise called Global Opinions that takes op-eds from international writers.

Prior to Trump, the Post also created a desk dubbed Morning Mix. It’s essentially the overnight team, but instead of writing up 2 am house fires, it first found its niche trawling the continents for grabby stories as likely to land clicks in Paris, Texas, as in Paris, France (a french woman stole $5.8 million worth of diamonds and replaced them with pebbles in an elaborate heist). In the Trump years, when the news cycle never paused under a President who’d tweet at 2 am, the squad evolved to help out with stories of bigger import. The Post has also relentlessly improved Live Updates, its breaking-news template, which dish out bite-size developments in big, ongoing stories and are often the most read pages on its website, a spokesperson says. It wasn’t the first with such a format, but its version is more reader- and mobile-friendly than others’.

International readership now makes up a third of total traffic, Ryan says. But the clickiest content has also been some of the most difficult to produce—meaning that going beyond that number will take work. The solution is not so unlike the Nerve Center that Buzbee helped AP establish: The Post has been spending big to set up 26 foreign bureaus as well as news hubs in London and Seoul.

“That’s not just for news gathering, but that’s for news production,” Ryan says. “It puts us in this position where 24-7 we can be breaking stories, we can be editing stories, we can be alerting on stories, and we’ll have teams of journalists with a full range of skill sets, from reporters to graphic artists to eventually videographers, to be able to gather news and produce it on a 24-hour cycle instead of the limitations of Washington business hours.”

The idea for the internationally based squads is first to target elites—“government officials, journalists, people in academic institutions,” Ryan says—with investigative coverage and analysis of the world’s power centers, businesses, and politics. One example: the recent Pegasus Project, a Post collaboration with 16 other news organizations that examined how governments all over the world used spyware made by an Israeli company to compromise the phones of politicians, journalists, and activists. From there, the bet is that the Post’s mix of breaking news and its eye for story curation (including those “Hey, Martha!” tales)—in bigger volume—can make inroads with less schmancy types, a not-imperfect analog to the way it went from being a paper for the gilded DC area to being a national read for a much more diverse group of people.

The business model starts with subscriptions, Ryan says. The Post offers a no-ads deal in Europe for about $85 a year after a promo period, a bit more than half the cost of a Premium Digital subscription in the US. This isn’t a new strategy in the global media business, but it is a new direction for the Post—and thanks to Jeff Bezos’s pockets, the company is ready to spend. Ryan draws a comparison to how the company had the luxury of staffing up before the 2016 election. He and Baron wanted to cover it aggressively, but Baron needed more people. They added to the political and investigative teams till they were larger than they’d ever been. Says Ryan: “We’ll be doing more of that overseas.”

If one thing is clear in today’s still-shaky environment for big, legacy newspapers, it’s that those companies need more than investigative journalism to survive. The New York Times has gone all in on service journalism and brand extensions that help readers navigate modern life—and the strategy is working. During its August earnings call, the Times noted that 46 percent of its paid digital subscribers last year came for the non-core-news products: its cooking app, its puzzles and games, its podcasts. (Soon, the Gray Lady will release a standalone subscription for Wirecutter, its consumer-tech app.)

Unlike the Times, the Post already has a foothold in the folkways of Gen-Z: its delightfully surreal TikTok.

The Los Angeles Times, which has soul-searched in recent years, is eyeing a related approach with Merida now at its helm. The paper “can become irresistible,” he told CNN’s Brian Stelter recently, if it finds ways to become “central to your lives.” Merida floated opportunities in entertainment—maybe comedy parties or DJ battles, “a broader kind of ecosystem of content you can wrap around the journalism. And compete for people who would not have thought about the LA Times before.”

The Bezos Way is a bit different, imagining that the Post might eventually become the world’s most read newspaper—a kind of “everything store” for information. Will it work? “I think there’s a challenge built into that strategy,” says Rick Edmonds, a longtime media-business analyst at the Poynter Institute. The Post is entering into a crowded market overseas, with competitors like the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, the Economist, and the Financial Times all fighting for the top-tier readers, and organizations like Reuters and, yes, AP—which now makes 40 percent of its revenue outside the US—aiming at the middle of the market. Politico has already built a lasting franchise covering EU news from Brussels.

The Post will have to convince people in its target markets to take it in addition to, if not in place of, the New York Times, which is better known outside the US. But, Edmonds says, the Post does have two great advantages: Bezos’s money and the sensibility it’s developed for re-reporting and amplifying around-the-world stories through channels like Morning Mix. “They’re tuned,” he notes, “to what makes a really good story.”

In its August earnings call, the Times noted the latent opportunity: “at least 100 million people who are expected to pay for English-language journalism and a unique moment in which daily habits are up for grabs.” For the Post, though, which hasn’t made the same kind of play for non-news audiences, the Trump slump sounds a cautionary note. In the second quarter of 2021, a spokesperson says, the company averaged about 20 million international readers per month—that’s a drop from what it had been during Black Lives Matter protests, the onset of Covid, and January 6. Hooking into other new audiences, in other words, will be key.

Ryan recently announced a task force, called Next Generation, led by an editorial and a business staffer, that will recommend ways for the Post to come for young readers. And in contrast with the Times, it already has a foothold in the folkways of Gen Z: its delightfully surreal TikTok account. A 30-year-old digital native named Dave Jorgenson launched the account for the paper two years ago, to the bemusement of some in the newsroom. Today, it has 1 million followers—less than Gordon Ramsay’s total but some three times what Washington’s NFL team has. (The Times has posted only one TikTok video; the LAT has a more robust account but only around 500 followers.) Post internal research conducted this spring found that about a third of its TikTok audience said they’d never looked at the Post before they encountered Jorgenson’s videos, and about 80 percent said they trusted the Post more than other news sources.

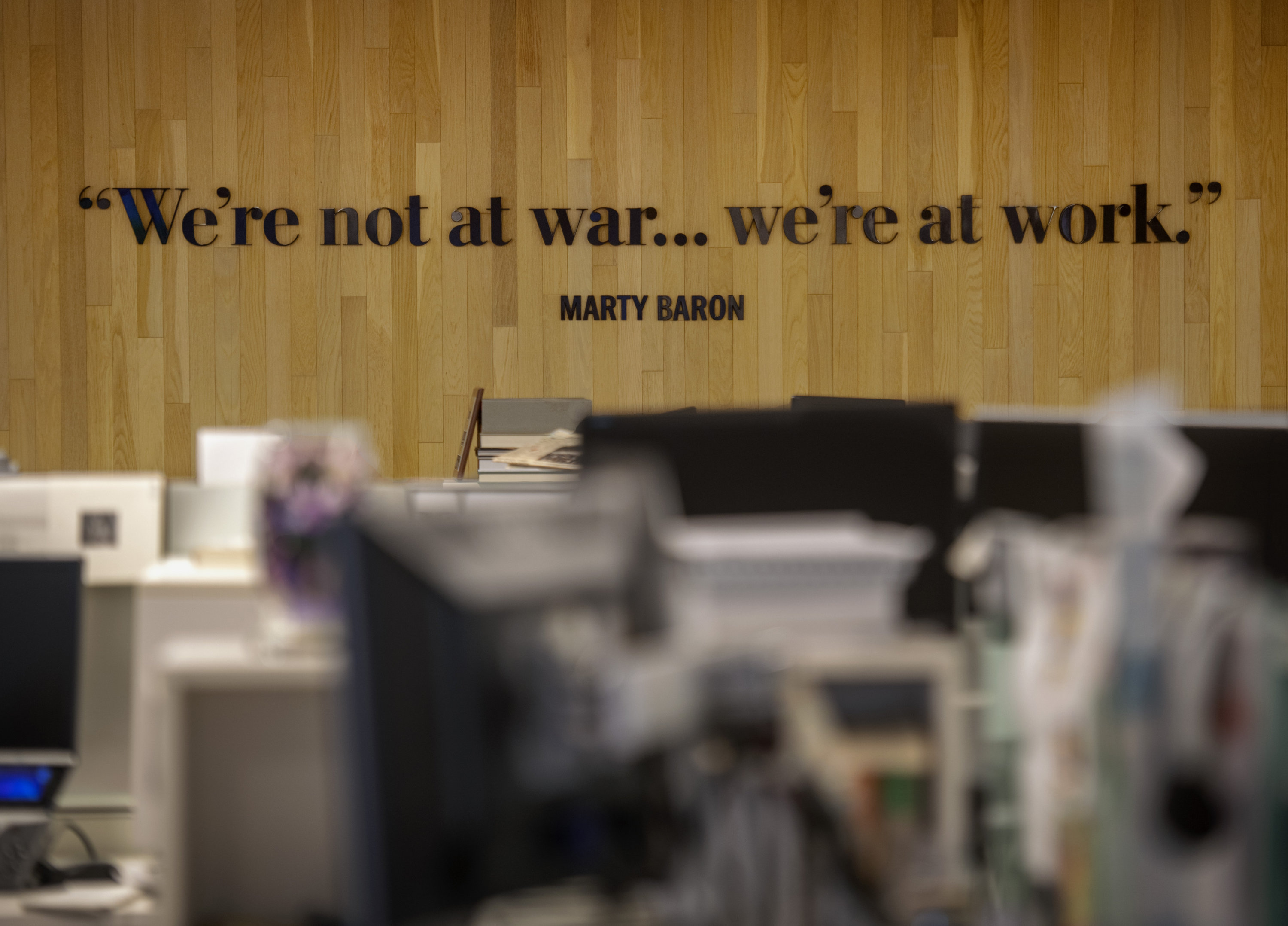

Buzbee took up residence in the newsroom in June, working from the K Street office most days—one of the few people to do so before phase one of its Covid reopening began on July 6. Two weeks into her tenure, a now-famous Baron-ism, uttered in response to one of Trump’s attacks on the paper—“We’re not at war . . . we’re at work”—was being mounted on a wall near the national desk.

Baron wasn’t a celeb-editor when he first took the gears, either, but between the 2015 release of Spotlight, about his work at the Boston Globe, and his steady stewardship of the Post during a right-wing administration determined to discredit it as fake news, he joined Ben Bradlee in the ranks of Post legends, becoming a boss whommany pined to impress with illuminating work. How does Buzbee follow them into the firmament of Post stars?

Baron led, in part, by stressing traditional journalism values—going to work, not war. Prizing objectivity above all else. But to some corners of the newsroom today—when any reporter can become a celebrity via Twitter and other social media—that approach feels distressingly out of date. The complexifier here, as Bezos might say, is that reporters with big social-media followings can help inject Post stories into the mainstream, and get even more attention by going on TV to talk about their work. Unfortunately, once you convince journalists they’re interesting, they tend not to shut up.

These struggles have been epic at the Post, where most of its social-media policy was written in 2011—an eternity ago in digital years. A plan to update it after Sonmez-gate went nowhere during Baron’s last year. And the newsroom is nervous about how Buzbee will handle it.

There’s little model for a social-media policy that doesn’t have unintended consequences. Ban journalists from tweeting about stuff that’s not on their beat? You could conceivably be forced to discipline, say, finance reporters who tweet about DC’s best hamburgers. Direct them simply to refrain from publishing anything that wouldn’t appear in the paper? Are you going to assign editors to review every proposed tweet or Facebook post? “I don’t see what the solution is here,” Elisabeth Bumiller, chief of the New York Times Washington bureau said during a recent roundtable convened by Politico.

Two people I talked to suspect that Ryan believes the Post has veered too far to the left and that appointing the chief of a newswire would be a good course correction.

Also complexifying: the intersection between the handwringing over social media and the generational changes wracking newsrooms. Baron clashed repeatedly with former star reporter Wesley Lowery over his Twitter account, but those fights were animated less by the content of Lowery’s posts than by what they represented: a debate between journalists who came of age believing their job was to avoid any tinge of bias in their work and often younger, more digitally inclined people who view the polite old rules of engagement as a formula for not calling out powerful malefactors. This generational dynamic—over things like whether to call Donald Trump’s falsehoods “lies” or how to describe police killings—has been around several years. But it may have reached its pinnacle last summer when Times opinion editor James Bennet got the boot after he ran an op-ed by Senator Tom Cotton that advocated sending federal troops to quell demonstrations. A generally younger set of staffers was horrified that their paper had run such a take. Traditionalists, meanwhile, were appalled that internal critics—unswayed by arguments that the section was designed to showcase diverse opinions—had unseated a heavyweight Timesman. Higher-ups at publications across the country have been worrying ever since about what “woke newsrooms” augur for their profession.

At the Post, the conundrum reverberates in all corners. During his editor search for Buzbee, Ryan asked several candidates about how they’d keep the newsroom under control, according to multiple people who have spoken with them. Two people I talked to suspect that Ryan believes the paper has veered too far to the left and that appointing the chief of a newswire would be a course correction.

Those who come to the Post from other publications often describe their surprise at how top-down its culture can be. The mythology of the place—Watergate! The Pentagon Papers! Snowden!—is so bright, it often blinds managers to how profoundly disaffected employees who aren’t white, pedigreed, political reporters can feel. For all the veneration of Ben Bradlee, it’s worth considering that he once put the kibosh on hiring a reporter because “nothing clanks when he walks.” Sonmez’s lawsuit alleges it was known in the newsroom that one of her male colleagues sent “an unsolicited photo of his underwear-covered crotch to a young woman” and was never banned from certain coverage the way she was. (The Post declined to comment on the lawsuit.)

Many in the Post ranks have hopes that Buzbee ushers in a culture that feels fairer and more humane. Her first big move came in late July when she named assistant national editor Lori Montgomery to be editor of the business desk. Before, only one other big department (features) had a woman at the helm.

Shortly afterward, Buzbee told staffers in a town hall that the paper will finally update its social-media policy, a process she plans to begin this fall. She said she hoped for a “collaborative” effort and a road map that reflects the Post’s standards of “accuracy, fairness, and lack of bias but that also balances that with our reporters’ very reasonable desire to interact with our audiences and with the world in authentic ways.”

Buzbee’s rollout to staff via Zoom back in June frustrated a good number of people who found her vague and given to platitudes. Since then, though, she’s been on a listening tour of the newsroom, and the early reviews are mostly positive—the word “disarming” comes up a lot. She is said to be frustrated that the lingering pandemic has kept the newsroom mostly empty—the all-staff return planned for mid-September has been delayed at least a month.

The Post declined to make Buzbee available for an interview. Instead, it provided a written quote: “Priority one has been to listen and learn. . . . The most important thing I could do in my first few weeks was get to know the newsroom, and I’ve been immersing myself in the reporting and digital operations and seeing where there are opportunities for growth.”

This article appears in the September 2021 issue of Washingtonian.