About 20 years since 9/11

This article is part of Washingtonian’s 20th anniversary coverage of 9/11. We talked to an Army chaplain who blessed bodies at the wreckage site about how he has coped in the years since the attacks, we reflected on how the fortification of DC after Sept. 11 changed our town, and we looked at the political legacies of 9/11, including which political careers were born of the tragedy. Read more here.

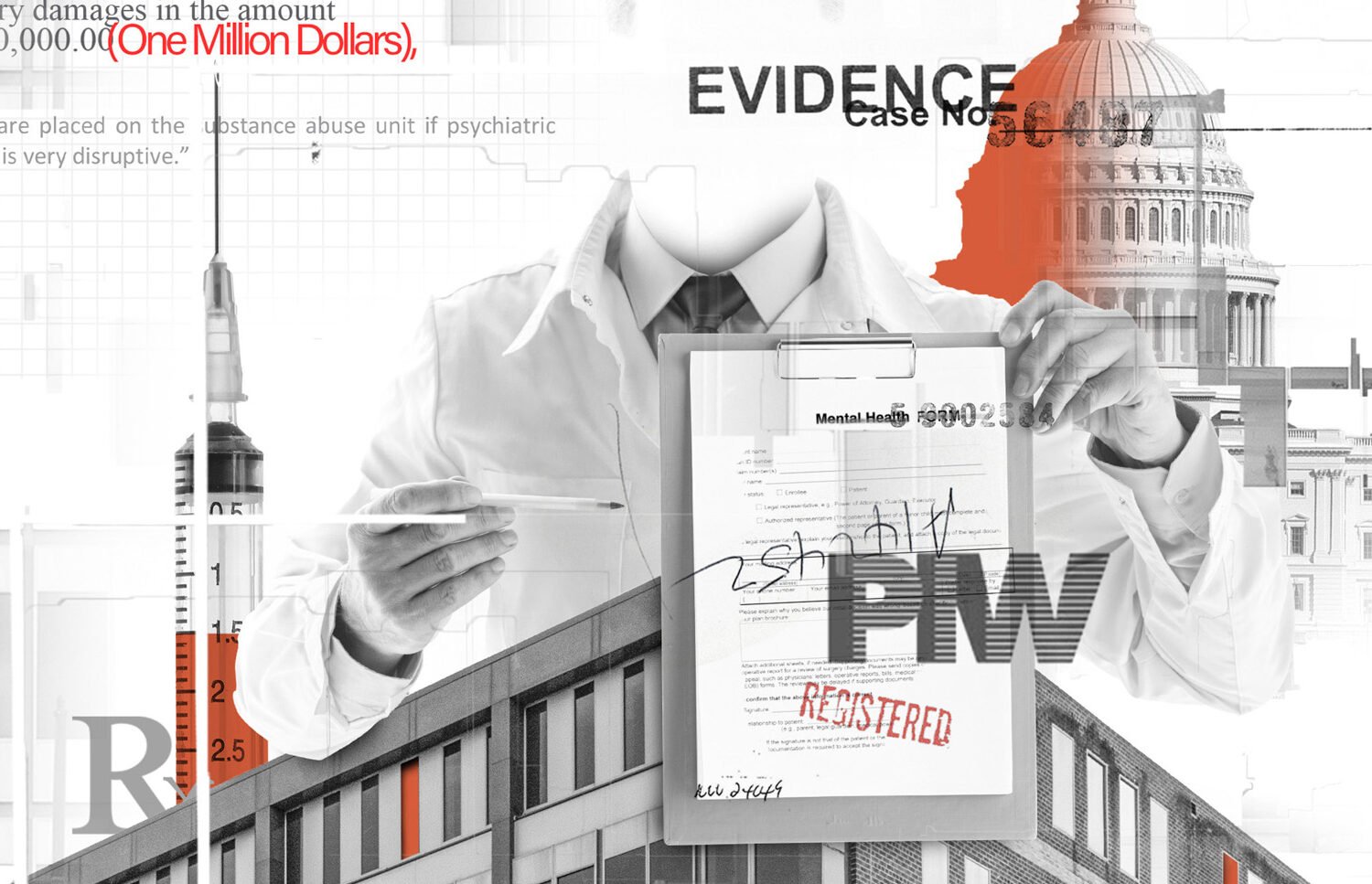

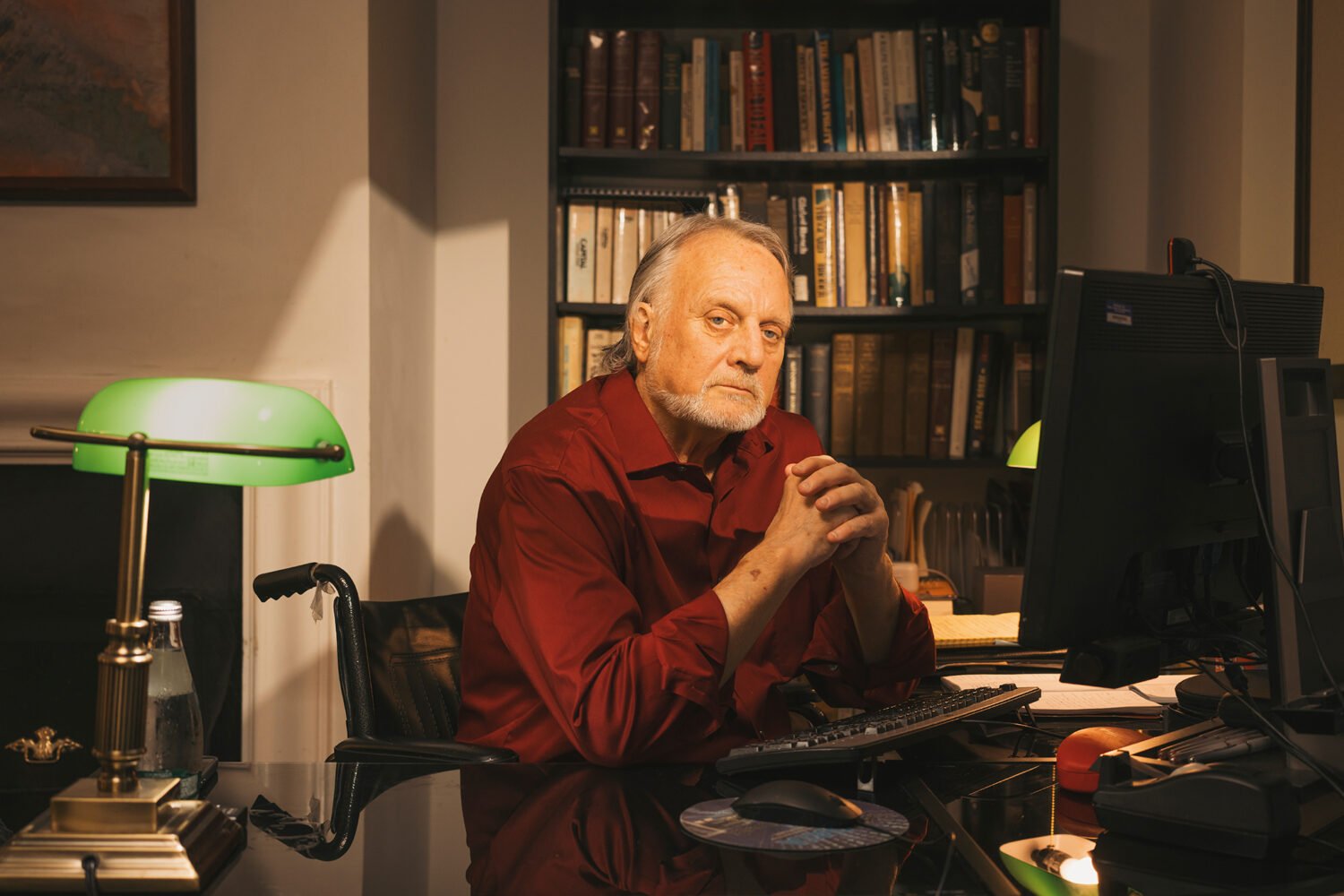

Terry Bradfield was an Army chaplain assigned to the Pentagon on 9/11 who spent weeks at the wreckage, praying over remains and ministering to victims and search personnel. Now retired from the Army and from a post-military job at Wesley Theological Seminary, he reflects on how the attacks shaped our lives in the decades since.

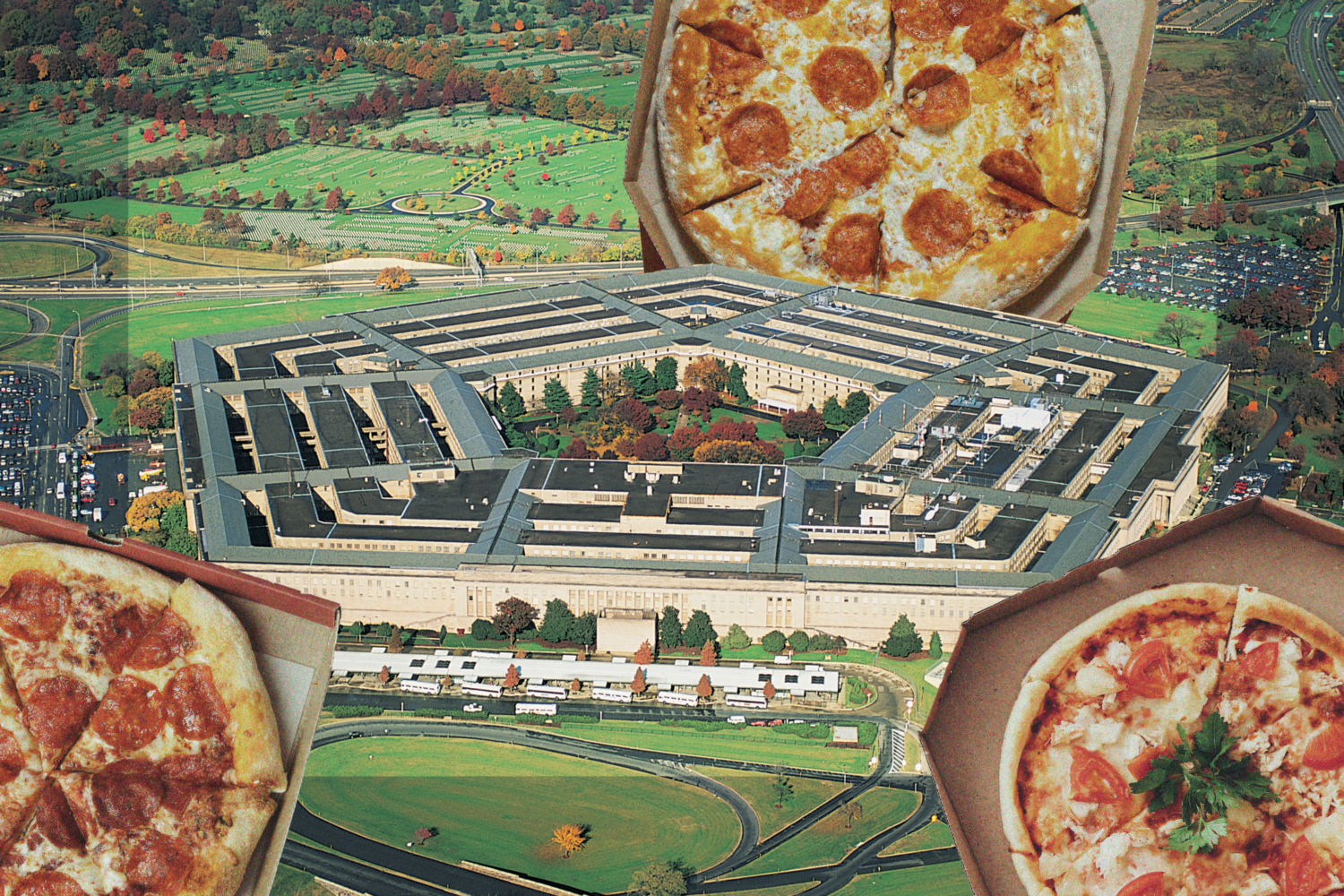

“It started out like any regular day. I’d drive in early [to the Office of the Chief of Chaplains in Crystal City], work out, shower, and be in the office by 8:30. I was hoping to meet one of my counterparts in the Pentagon. And just as I walked out of the elevator, the bus pulled away. If I’d caught that bus, I would have been one hallway in from the impact. I wouldn’t have survived.

“I got [back upstairs] and somebody said, ‘There’s a report of an airplane hitting the towers.’ We were watching the TV and saw [through the window] a huge black cloud erupt from what obviously was the Pentagon. Then one of the commentators said they’d just received word that a plane crashed into the Pentagon. That’s when everything went kaflooey.

“I managed the phones that day and tried to get a couple hours’ sleep on a couch that night. The next morning, I went to the site to help. It was a horrendous sight. The plane’s right wingtip would have been right where the door of my old office was [before the chaplains moved out during renovations]. It was devastating, to the extent of being sick, looking at the place where all of these people I worked with had perished.

“My primary position was with the mortuary van. I would assist with bringing the remains into the van, where a doctor pronounced death. I would then honor those remains. Sometimes I’d read a quote from Scripture or say a prayer or just mutter something absolutely incomprehensible, I’m sure. We almost never received anything that was recognizable as a human being.

“One time, we shut the door of the van and all four of us stayed inside. I remember sitting in the absolute darkness and chill, not totally uncomfortable, losing myself in thoughts. I didn’t pay attention to who was alive in that van. But I was very aware of who was not alive.”

“I had phantom smells for almost ten years. I’d get a whiff of something and I was back at the rubble pile, just like that. I’d have sort of a sinking feeling, a hollowness. Sometimes I can still see individual stones in that pile, at that place.

“I have a very strong compartmentalization tendency. I put things in drawers and shut the drawers. I acquired a lot of anecdotal lessons, nice little stories that make you feel good, that I can pull out in a sermon or in a talk. But I also know the wrapping of those things are all of my emotions. If I can get the emotions unraveled to get to the thing, then I’m doing good. If I can’t, I’ll usually find myself in tears. I’ll go off by myself until I can get the wrapping back in place. My wife said it’s PTSD, and I said, ‘I’ve never been diagnosed, so it isn’t.’ I have not spoken to a therapist about it.

“My wife knows when something in the news or in general has affected me. She says I go silent. I used to never shut up when I was upset about something; I just talked about it until I got it worked out. Well, now I work it all out silently. And not just for a few minutes—this’ll be a days-long thing.

“The building collapse in Miami [this year] brought it all back. Those pictures of the dogs, the rubble pile—any of us who were at the Pentagon or Ground Zero, we have a really good idea of what went on down there. The force of feelings they’re having. I remember rescue guys hiding in the Pentagon rubble so that the dog could find something alive. I asked them about that and they said, ‘We have to do this for the morale of the dog. The dog gets discouraged if all it ever finds are remains.’ I said, ‘You think that dogs are the only ones who get discouraged?’ ”

“I had a fairly rosy view of life before this happened. I’d been in the Army for 19 years at that point; I’d seen enough that could have made me a little more hard-hearted. But I wasn’t. And [the attacks] changed my general outlook on the natural goodness of the world. First of all, I was downright pissed off that somebody had the gall to ram airplanes into the Trade Center and the Pentagon and think about doing it to the Capitol or the White House. There were some of us who could list, let’s just say, a lot of folks we had worked with in one capacity or another who were [killed].

“We got bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I was very much opposed to those actions. I made that known to my superiors, which wasn’t necessarily smart. In 2004, I asked the bishop not to reappoint me. I retired. And it was mostly because I had a hard time letting go of the personal insult of the attack. I think I eventually got to the point where I was able to let go of that notion. I still have a strong core of optimism about me, but I have a fairly tough veneer of realism now—it’s more brittle than before 9/11. So the optimism isn’t able to pop through quite as easily.

“I think immediately after, there was a strong sense of shared grief, to some extent shared resolve, a sense that there was something greater than ideological differences that tied us together. For anybody who came around 395 and Route 1 to get to work—and that was a huge number of people—all the construction at the Pentagon was a strong, visible reminder. I think that feeling lasted pretty much into that first year.

“But I think we went back to a fairly normal existence. I think that’s the nature of who we are as a people and a culture. We’re very tribal, very insular. Our memories don’t last very long. We tend to go back to our old ways very quickly. I saw people do just what I did: put it in a drawer and lock it away. Now you’ve got 20 years of people who weren’t even born when the attack happened; another huge part of the population is no longer alive to remember it. I think the glue that was squeezed out of the tube then is all dried up now. It’s no good to hold anything together anymore.

“When I was still working, I usually took off on 9/11. I got away from the phone and computer and went out to hike or golf, anyplace where I could get away from the images. I think [my peers] have soldiered through. You think about it occasionally, and if it’s just you and the buddies, you’ll talk about it and raise a glass to the memory of those that were lost, which helps you to then identify your particular losses and all of that. Then you say: That’s enough of that. Let’s get back to living.”

This article appears in the September 2021 issue of Washingtonian.