“I thought I would die eating cured salami,” says Margaux Riccio, starting in on the unlikely story of how she came to be the vegan co-owner of one of the buzziest new plant-only restaurants in Washington—and also the nemesis of a lot of people who would be her natural customers.

The place is called Bubbie’s, and the tale goes like this:

Riccio grew up around her father’s California steakhouse, among a big meat-eating Italian family. She started cooking at the Atlas Room on H Street, Northeast, in 2010, but two years later she was forced to quit the kitchen, stricken with hives and mysterious allergies. When doctors eventually diagnosed one of the main culprits—dairy—it was ruinous for a chef who liked to hit Bistrot du Coin for ham-and-Gruyère tartine and crème brûlée on her days off. Her partner was vegetarian, so suddenly there was not only no prosciutto or lamb in their home, but no milk or fresh mozzarella, either. “I was just starving,” she says.

Riccio started experimenting with plant-based cooking, crafting a passable imitation chicken from wheat gluten and tofu, and a feta from soy. She made everything by hand, manipulating the ingredients so the resulting proteins would exactly mimic the foods she missed. In 2016, when she was able to get back into a professional kitchen full-time again, she was functionally vegan. And an innovative vegan cook.

That year, she started cooking at Pow Pow, a new fast-casual spot on H Street whose Asian-oriented menu was stuffed with rice bowls and “egg rolls the size of your arm.” Riccio began working some of her meat-free creations into the mix, so that eventually the restaurant pitched a mirrored menu. Every dish could be made vegan.

It sounds simple, but picture the average restaurant menu: Even now, in our supposedly veg-friendly culture, vegan offerings are typically tucked into a corner like afterthoughts. Not only that, but Riccio’s non-meat options were wild replicas of the real thing. Vegan diners would pepper Pow Pow staff with questions about the food—how had they converted chickpeas into such a delicious simulacrum of pork? But Riccio refused to emerge from the kitchen to talk it up. “I hid in the shadows,” she says. “I didn’t want to come out as a plant-based chef.”

For one thing, she’s a bit shy. But she was also a woman toiling at the culinary fringes, smack in the age of competitive butchering and of cooks who worshipped at the altar of offal-loving bad boy Anthony Bourdain. “I had already taken enough stuff with being a female chef to begin with,” says Riccio. “And then to change completely to being just a plant-based chef?” No. It was too marginal.

But two years into the venture, Shaun Sharkey, Riccio’s romantic partner, who was also a partner in the restaurant, was itching to take Pow Pow 100 percent vegan. Riccio, feeling more confident, was ready, too. “We were passionate about it,” Sharkey says. His business partners, though, weren’t sold.

So Sharkey asked Riccio to secretly whip up a completely meatless and dairy-free version of Pow Pow’s summer menu for a meeting of the owners. “At the end of the meeting, he says, ‘What do you think of the new meats and cheeses?’ ” recalls Riccio. “Our partners said, ‘It’s great, it’s great,’ ” at which point Sharkey copped to the ruse. “He tricked them.”

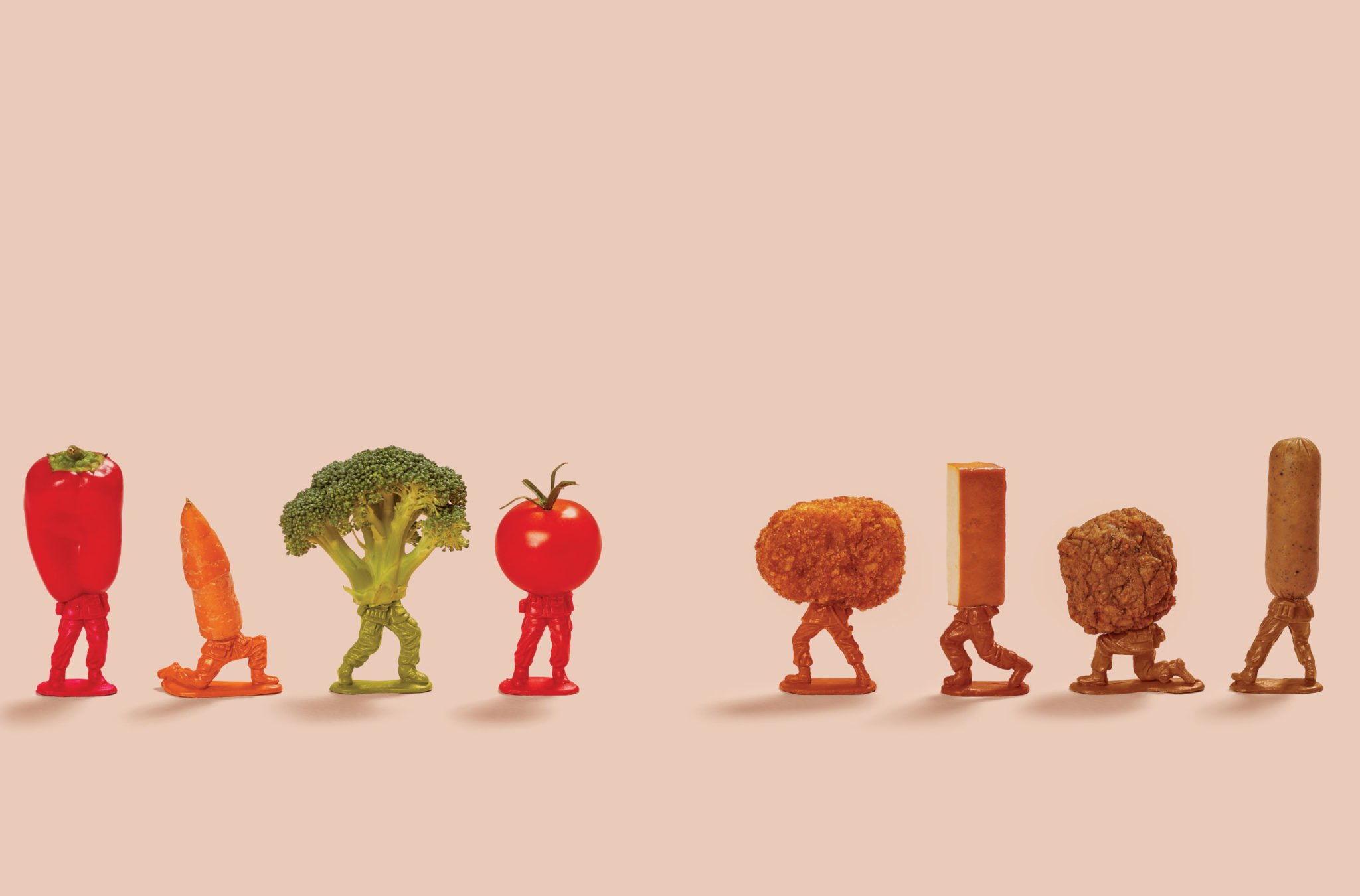

See, in certain plant-only circles—what Riccio would tell you are the non-militant ones—the Holy Grail is fare that’s good enough to fool carnivores. Savory fake bacon. Tender wannabe beef. Poser food. Riccio owns the genre. Rocking her polka-dot kerchiefs and wickedly nostalgic culinary vibes, she’s nailed the plant-based versions of the foods she’d kill to eat again.

After taking Pow Pow fully vegan, she and Sharkey launched Bubbie’s Plant Burgers & Fizz as a pop-up, selling “pork belly” on Texas toast and delectably greasy “sausage” biscuits: decadent, diner-style vegan food that goes down perfectly with a hangover, or maybe after a ten-mile run on the Mount Vernon Trail. From there, the couple opened Plant Food Lab, a Dupont Circle incubator to experiment with vegan concepts before spinning them out around DC, installing Bubbie’s as the first occupant. Then Riccio cofounded a wholesale vegan-cheese outfit, too. (Her absolute dream: Drive to a Wawa, buy a deli sandwich loaded with her Muenster cheese.)

Between the standalone restaurants she hopes to seed around town and the ones she’s already supplying with her cheese, Riccio is assembling a mini-empire to feed diners who have spent the entirety of their vegan-eating lives pining for “chicken” that doesn’t chomp like rubber.

But here’s the thing: Amid all her success, she still can’t bring herself to identify as vegan. And there’s a whole tribe of plant-only diners who look at chefs like her and instead of seeing triumph—more people for the cause!—they see sellouts, people who cater to animal-eaters, even in fake form. “Vegans hate me,” Riccio says, and laughs.

Vegan dining is only newly mainstream, but Washington has a long history with the cuisine. For decades until 2012, Soul Veg, a mac-and-cheese cafeteria-style restaurant near Howard University, was a cultural outpost for the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem, a group who believed that eating vegan was the key to eternal life. In the 1990s, Delights of the Garden in Georgetown was one of the it spots. “It was a Black-owned restaurant filled with young Black people,” remembers Tracye McQuirter, a nutritionist and the author of By Any Greens Necessary, a guide to going vegan for Black women. “That’s where we would go on Friday and Saturday nights and hang out and listen to poetry, hear live music, and eat raw vegan cuisine.” The scene was small but vibrant, pioneered by Black chefs who came to it with spiritual or political designs, or for reasons of personal health.

The gastronomic virtues of the food, though, didn’t always match the virtues of the intent. This wasn’t just true around DC. Without enough of an audience to justify blue-sky innovation, there’d never been an incentive for chefs or producers to bother experimenting much with fare that mainstream food culture considered hippie-dippie. And for vegans who enjoy eating not only for sustenance but for pleasure, too—yes, that’s a thing; I say this firsthand—the landscape often felt horribly bleak.

All that’s changed over the past decade or so, as eating became a political act for a much wider swath of people. In the post–Omnivore’s Dilemma era, when more people are skipping meat until 6 and the $14 salad is ubiquitous, the customer base for veggie and vegan fare has gentrified. So have the ambitions. Where vegans had long settled for plasticky imitation cheese and mushy, tasteless “burgers,” suddenly startup money began flowing as investors saw a payday among a new food elite: a generation of consumers who lean gourmet but don’t want to spend their food dollars flying in Wagyu beef and destroying the climate.

The Silicon Valley venture-capital firm Kleiner Perkins and the Gates Foundation pumped funds into Beyond Meat, an LA company that figured out how to turn pea protein into a remarkable look-alike of beef. That in turn sparked a startup craze of plant-based burger joints. (Beyond has a similarly flush competitor, Impossible Burger.) Vegan food has gotten . . . insanely good. Which no plant-food-loving person would have said even five years ago.

But not shockingly for anyone who followed the fights between Big Beer and its upstart craft rivals, to take one example, as the vegan scene has blown up, so have all kinds of ideological factions and (sometimes amusing) stylistic clashes among its faithful.

And Washington—home of frenetically innovating small-batch chefs like Margaux Riccio but also a burger king looking to become the Vegan Burger King—happens to be a hotbed of the philosophical debates.

You might remember Spike Mendelsohn. He launched his first Good Stuff Eatery on Capitol Hill in 2008 after a stint on Bravo’s Top Chef as the Chicago season’s fedora-wearing fan favorite. The burger restaurant was a go-to for Obama-administration types, and it helped vault Mendelsohn into a wonkier sort of VIPdom, inside the food-policy world. In 2015 he became chair of DC’s Food Policy Council, and in 2017 he met Honest Tea cofounder Seth Goldman while sitting on a local panel. The Bethesda entrepreneur was executive chair of Beyond at the time and gave Mendelsohn a packet of patties. “Just try them,” Goldman said.

Mendelsohn was skeptical. He’d been disappointed by other imitation burgers—watery patties that fell apart in the pan. But when he fired up a Beyond, he says, it “cooked perfect—that perfect texture and the Maillard reaction you look for,” referring to the browning caused when sugars and amino acids combine.

He started thinking about his own household. His wife is vegan, and he’s flexitarian—or, he jokes, the “very loose term [you] hide under” when you trend vegetarian but aren’t dogmatic about it. Flexitarians would dig beefy vegan burgers. And there are a lot more flexitarians than vegans. (According to one study, by the market-research firm Packaged Facts, some 36 percent of Americans consider themselves flexitarian, while only 3 percent eat vegan.) By 2019, Mendelsohn and a team that includes Goldman’s son, Jonah, were opening a chain called PLNT Burger, with plans to build it into the fast-vegan spot, and not just for Washington. Says Mendelsohn: “I’m pretty much my customer, right?”

The first location was inside a Whole Foods in Silver Spring, all oranges and teals and purples, the bright beachy vibe accented with peppy, live-green aphorisms like eat the change you wish to see in the world. In less than two years, PLNT has opened in eight others of the grocer’s stores across the Washington area and Pennsylvania. It wants to grow throughout the Mid-Atlantic and beyond Whole Foods, serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner from scores of locations, eventually including drive-throughs, too.

The pace of expansion would have been unthinkable not that long ago. “If I had opened a veggie-burger spot in 2002, nobody ever would have come,” says Doron Petersan, who instead opened a popular vegan bakery, Sticky Fingers, in Dupont that year. The proposition is totally different now. “Omnivores will see: ‘Oh, Spike Mendelsohn is putting his name on this burger—it has to be good,’ ” says Jonah Goldman, PLNT’s head of marketing. “And they’ll open their minds and open their mouths.”

To certain vegan eaters, a planet full of PLNT Burgers would be nirvana. The heart of Mendelsohn’s menu is a slate of Beyond Meat burgers, customized with his chef’s touch and layered with flavors. One version of the “Steakhouse” I tried was piled with lid-melted “provolone,” shoestring potatoes, steak sauce, and an impossibly savory mushroom “bacon”: a punch-you-in-the-face experience when you’re used to bare patties with bitsy carrots poking out the sides. Who cares if you’re eating it next to a tableful of omnivores? Delicious, reasonably priced fast food (PLNT’s sandwiches start at $6.95) as accessible as a Whole Foods—yes, please.

Unless you’re in the crowd who can’t stomach the thought of a vegan industrial complex. “His business model seems like McDonald’s,” says Riccio. “We’re never going to beat their prices.”

Don’t get her wrong: Riccio loves the idea of more casual flexitarians and even die-hard carnivores discovering the food. “He’s going to bring more people in that might, like the bros, not [otherwise] be okay with it.” But she worries about how chefs attempting to do something more independent, on a smaller scale, will compete with the corporate types.

Mendelsohn understands the knock. “I get access because I am who I am, right?” But no, he is not about to apologize for joining forces with Big Vegan.

His argument: He can offer cheffy feedback to vendors that could help make their food even better. Going mass market lowers retail costs, no small matter given vegan food’s bougie reputation. And is there any food more spiritually, culturally American than the burger? Shifting market tastes toward plants can help break the link that so many of us have between celebrating the good things in life and eating meat. Says Mendelsohn: “You only have real, effective change in our food system when you scale.”

From a purely economic standpoint, it all makes sense. But there’s a card-carrying class of purists—Vegan People, as Riccio thinks of them—who’d be less than psyched about a chef who made his name in red meat now authoring and benefiting from a change for the social good (regardless of how good).

The Vegan People are one of the reasons Riccio doesn’t like to describe herself or her food as vegan.

She told me about the spat she found herself in after she started selling her cheese wholesale to other restaurants, some 70 pounds a week alone to Call Your Mother, the (non-vegan) bagel joint in Park View and Capitol Hill. Call Your Mother’s bagels contain honey—which is shunned by some vegans over what they see as the exploitation of bees. “They came for me on Instagram for that one,” Riccio says. “But I put an asterisk on it, saying, ‘Order it with rye!’

“And they still came for me. We keep pointing out, ‘If you’re 100 percent vegan, that’s great. I’m not going to argue with you about honey. But my thought is: You’re ordering [my] cream cheese now because it’s close enough.’ ”

Unapologetic vegan Ran Nussbacher, cofounder of two restaurants called Shouk, is all good with the idea of competing with a carnivore. “Somebody like Spike, who does, yes, generate a lot of revenue from sales of meat but is also spending time making plant-based burgers more accessible is exactly the kind of stuff you love to see,” he says.

Raised on the veggie-forward cooking of his native Israel, Nussbacher came to the US to study at Brown. In 2008, he arrived in Washington to work for Opower, part of a young crew who turned the software firm into one of the area’s hottest tech companies. The firm set out to convince people to lower their energy consumption through gentle prodding, such as usage reports adorned with smiley faces when they consumed less than their neighbors; in 2016 it sold to Oracle for $532 million. Having a front-row seat for a grand experiment in behavioral science helped give Nussbacher the idea for Shouk, a business that might tackle climate change from a different angle.

His partner, Dennis Friedman, is the chef in the venture, while Nussbacher brings the MBA and the change-the-world intensity of early Silicon Valley types. Their first Shouk opened in 2016 on K Street near the convention center, a second in 2018 in the Union Market area of Northeast DC. Unlike other plant-forward spots, nothing about the branding or the aesthetic of Shouk telegraphs the agenda: With its warm woods and weathered-tin counters, it just feels like a cool place to eat. The fare—mushroom shawarma, eggplant patties—is inspired by the street food of Nussbacher’s youth. But honestly, you’d have to study the menu a minute to realize it’s vegan. And that’s by design. “It’s not weird food,” he says. “It’s just great food. There’s no need to label it.”

Which is to say that Nussbacher is all for a Vegan Burger King democratizing plant-based food, but like certain Vegan People, he has a philosophical beef with those who insist that it also resemble or taste like a meat-eater’s dream.

Shouk’s signature veggie patty contains a dozen ingredients with recognizable names—cauliflower, black beans, oats—cooked separately before being combined. And the patty still looks like cauliflower, black beans, oats. “It’s not trying to hide anything,” Nussbacher says. “We want to connect people to the idea that eating vegetables in their natural form can be delightful. An important part of this shift is to reconnect people to actual vegetables, to actual plants, not just food tech.”

Other DC vegan hot spots showcase veggies in all their glory, like H Street’s Fancy Radish with its charred baby beets, or Elizabeth’s Gone Raw, south of Logan Circle, and its caramelized parsnips. But a lot of the most popular stuff in Washington right now is the poser fare—soy-based “crabcakes” at Senbeb, Harmony Cafe’s sweet-and-sour “shrimp,” NuVegan’s wheat-gluten “chick’n” drummies, much of Margaux Riccio’s menu at Bubbie’s.

Some customers who walk in can get pretty fired up. “Vegans yell at me constantly about my pork,” says Riccio, “like, ‘Why would I want to eat something that tastes like pork?’ ” Or “ ‘I don’t want things that taste like a dead animal. What do you have that’s not?’ ”

For fun, I called PETA for its take on Vegan vs. Vegan, thinking the hard-line organization devoted to the ethical treatment of animals probably held a hard line on the issue. Nope. “Make it in the shape of a whole chicken or suckling pig, for all I care,” Ingrid Newkirk, president of the Dupont Circle–based group, told me. But the message was not exactly unified. Lisa Lange, the organization’s senior VP for communications, said, “If we’re making ‘turkey’ look like turkey, we’re perpetuating the idea that turkey are ours to eat, and they’re not.”

When people ding Mendelsohn for slinging plant burgers without swearing off meat, he tries logic. “Listen,” he says, “I’m doing my best, and you want me here” as a translator to the carnivores. “Like, I understand the Philly cheesesteak,” he says—he knows what they’re supposed to taste like. “I’m happy to talk to those people, to hand out free hugs, do whatever I need to do. But I think I’m doing the transition my way, and I think I’m doing it the right way.”

To Riccio, the purity tests are mostly a sideshow. When she was cooking at Pow Pow, a Chick-fil-A opened nearby. She didn’t like the corporation’s practice of donating to groups with anti-LGBTQ+ stances. So on Sundays, when Chick-fil-A is closed, she started selling a limited-edition fried-chik’n sandwich. People crushed her ordering system to get their sammie before the day’s batch sold out, debating whether to have it naked or stuffed with cashew mozzarella. Could every one of those customers have been a veg-head? She doubts it. And how will plant-based food ever ditch its elitist rap if her kind of vegan people don’t broaden the tent?

But the restaurant business is a customer-service business, so Riccio tries to read the room rather than argue with it, steering people to what she suspects will fit their palate and their politics. Out-in-the open vegans are nudged toward her beet burgers, independents and carnivores to her “pastrami.”

Just please don’t get partisan about it. “I need you to say my food’s good,” she says. “I don’t want you to qualify it as ‘good for vegan.’ ”

At the time Mendelsohn and his partners were mocking up brand concepts and recipe-testing for PLNT Burger, Duane Cheers was trying to get his own vegan burger business off the ground and was struggling.

Cheers had grown up in Prince George’s County, graduated from Morgan State University, and spent his early adult years trying to make it as an entrepreneur, having both a house and a car repossessed. For decades, he’d watched his mother help manage her lupus by eating a vegan diet but struggle to find foods she liked. He teamed up with a friend, Danita Claytor, whose own mom had strained to eat healthy after a cancer diagnosis, and with Jumoké Jackson, a chef and caterer who got his start at Ben’s Chili Bowl and was known in the business as Mr. Foodtastic. The trio worked up different burger variations, cooking by hand and trying to stray from the meaty imitations they’d tried. They wanted to make a good veggie burger, targeted at Black eaters. It didn’t need the mouthfeel of red meat. It didn’t have to bleed. They didn’t have access to food technicians or a lab. And anyway, as Cheers puts it, they didn’t want to be Jurassic Park.

The winner incorporated pea protein, hemp powder, pepper sauce, and mango concentrate. It’s GMO- and soy-free, and it doesn’t leave you with a leaden stomach the way the meatier concoctions can. There’s no sacrifice on taste—the Everything Legendary burger is a flavor-packed patty. Yet even though the burgers were a hit at local pop-ups, the company was having trouble getting traction.

Cheers went to Baruch Ben-Yehudah, a pioneer in the DC vegan world who got his start in the restaurant business with the Hebrew Israelites and eventually ran his own cafeteria-style spot, Everlasting Life, in Capitol Heights. Cheers had eaten at Ben-Yehudah’s place for years with his mother and hoped he’d put the burgers on his menu. But the pitch fell flat. Dr. Baruch, as Ben-Yehudah is known in vegan circles, loved the healthfulness of the patties, but they were pricey: $45 for a four-pack retail. Everything Legendary didn’t have the production capacity to supply a restaurant, or the money to get there. And Cheers was struggling to secure funding through traditional channels, running the company mostly off a credit card.

Then, this past February, Cheers and his partners landed a slot on Shark Tank, the TV show where entrepreneurs try to sell a panel of celeb investors on their concept. The sharks devoured the product—and Cheers’s turbo energy. After Mark Cuban, a vegetarian, declared that he was putting down $300,000 on a $1.4-million valuation and taking a 22-percent stake in Everything Legendary, Cheers started yelling, “That’s what I’m talking about, man! That’s what I’m talking about!” and body-slamming his partners like a come-from-behind victor at the Super Bowl.

Everything Legendary is using the money to ramp up production and is selling its patties in more than 300 Targets in 28 states. “When you talk about me,” says Cheers, “someone living on someone’s couch—I was renting out a basement room from a lady who didn’t even have a pullout couch, just a regular couch—and where I am now, you’re talking about $2.1 million in sales since Shark Tank launched. That’s in five months—life literally changed.”

Cheers says he won’t let himself spend more than four consecutive nights at home before hitting the road to promote the patties. He’s in supermarkets constantly, checking to make sure Everything Legendary is shelved as its contracts insist upon—and if not, he’ll start moving things around. He loves talking up customers. “When I go into Safeway, let me see somebody pick up some Beyond Burgers right in front of me: I’m gonna make ’em put it down. . . . I’m like, ‘Have you heard about Everything Legendary? Did you know this company was just on Shark Tank? Did you know they’re from the DC area? Did you know that they’re Black-owned?’ ” He goes on. “I’m like, ‘Yo, here’s my cell-phone number. You go try the burger. If it’s not good, give me a call and I’ll get you the money back.’ ”

Cuban’s funding has helped Everything Legendary drive down its prices to $7 for a two-pack now, but that’s still about 75 cents more per patty than Beyond’s. Cheers calls his burger the Rolls-Royce to “the other guys’ Toyota,” pushing its origins in a chef’s kitchen, as opposed to the laboratory of a food technician. The bet is on the plant-forward eater who trends health-conscious and leans more purist than the one in search of the guilty pleasure. “Not meat. Not trying to fake it either,” as its marketing pitch goes.

Unexpectedly, the pandemic has been a curse and a boon to Cheers and his rivals—a curse because Covid levied an awful precariousness upon restaurants and their suppliers, but a boon because talk of the virus’s origins in China’s wet markets has more people thinking about what they eat. DC is already considered prime vegan territory: One recent tally by the Vegan Word blog ranks it third in US cities in terms of the density of vegan restaurants, with 3.6 per 100,000 residents. (Portland, Oregon, is first.) The most prolific purveyors in the scene all hope it will grow bigger still.

This fall, PLNT is establishing a beachhead in Manhattan by opening its first standalone burger joint in Union Square, while Nussbacher has just begun selling Shouk patties online and nationwide, and will soon launch restaurants in Bethesda and Rockville. “This is where consumers want to go,” Nussbacher says, noting that he hopes to eventually open “hundreds” of Shouks.

Riccio and Sharkey are preparing to open Bubbie’s as a standalone restaurant in Adams Morgan. They’re in talks to bring other concepts through Plant Food Lab—one Bolivian restaurant has expressed interest—and they’ll soon use the space to test out Cenzo’s Upper West Side, an all-vegan Italian deli. (The incubator is designed so that all logos and other branding can be swapped out in less than a week.) Dine around town and you see Riccio’s Vertage cheese increasingly popping up on menus—at Donut Run in Takoma DC, Cielo Rojo in Takoma Park, and Andy’s Pizza (in Navy Yard, NoMa, Shaw, and Tysons).

Cheers is making inroads now, too. Although he’s mostly focused on grocers, this past summer, post–Shark Tank, he called on Everlasting Life again. This time he made the sale. “We benefit from his exposure,” says Ben-Yehudah. The burgers are on the menu alongside Ben-Yehudah’s mac and cheese, drumsticks, and garlic kale salad, the mainstays that have kept him in business for decades. In 2014, he opened a storefront in Takoma, and in 2018 inside the Anacostia Arts Center. Now in his mid-fifties, Dr. Baruch has been at this just about longer than anyone in Washington, long enough to remember “when it was just a couple places to go to.”

Not that that’s stopping him from adapting to changing times. This year, he started the process of switching the restaurants’ name to Elife. “ ‘Everlasting Life’ has a religious connotation,” he tells me. “Too many people thought we were a church.”

This article appears in the October 2021 issue of Washingtonian.