When you pull up to the CIA headquarters in Langley, you have to shout your Social Security number out the window into a speaker, like when you’re ordering fries at a drive-through. Much like the Union that the Agency was formed to protect, the system, it seems, could be more perfect. But I am willing to do what it takes to get the inside story of how the CIA is recruiting and working with the next generation of spies.

One would think it’s basically impossible to get millennials and zoomers into covert jobs. The youngest of this bunch of young people have spent their entire lives online, some since their parents blasted out their first ultrasound picture as a pregnancy announcement, before they’d even gained sentience. If the whole point of being a spy is that nobody knows who you really are and no one can ever find out, how exactly are you supposed to achieve this level of anonymity when you’ve flung untold reams of identifiable content across the digital world? I intended to find out.

So I made it through the visitor center (leaving my phone behind in a locker), drove past what I’m told is a very contentious parking situation where lots of spots are so far from the office that a shuttle has to transport employees from their cars to their desks (a spy’s supposedly glamorous life actually laced with drudgery and inconvenience—how very John le Carré), up to the Original Headquarters Building, with its bright, imposing marble lobby (the one you’ve seen on TV, with the CIA seal in floor tile and the memorial stars carved into the wall), down a hall lined with photos and well-wishes from past Presidents (Trump’s thick Sharpie scrawl, visible from afar, shouts in all-caps, “I’M VERY PROUD OF YOU! YOU ARE THE WORLD’S BEST!”), and through a museum, where items on display include a gun swiped during the bin Laden raid and the gym bag of a young woman who died on Flight 93, her luggage tags from 9/11/01 still attached.

My meeting with Michael T. Burns, associate director for CIA talent, took place in the Office of Public Affairs conference room, a windowless space that, hilariously, is decorated with framed posters of spy movies and TV shows: John Krasinski as Jack Ryan, Daniel Craig as James Bond, a black-and-white photo of The Americans cast doing a panel, alongside CIA formers, called “Reel Life vs. Real Life.” I’m told, many times by many people, that Hollywood portrayals of Langley and of spycraft more broadly are wildly misleading and totally inaccurate—“Everyone thinks it’s like 24, but it’s really more like The Office,” Burns joked—but evidently these depictions don’t bother them too much.

Before I arrived, I’d had a decent number of people say they couldn’t tell me much about how the CIA chooses its young new recruits. But surprisingly, I’d also heard that online footprints don’t necessarily eighty-six your chances. “Most folks that are applying to jobs in the intelligence community have kind of prepared themselves and their portfolios and lifestyles for such an application,” Lisa Maddox, who worked at the CIA from 2008 to 2018, told me. They’re shrewd enough either to be circumspect users of social media from the start or to review (and delete) old problematic tweets and posts. Plus, “the CIA is a pretty modern, savvy organization,” Maddox said. “They want and encourage most officers to have a social-media presence because, quite frankly, it’s a red flag and it looks strange if you don’t. You’ve got to blend in and look normal.” Actually, she speculated, “I would argue that some of the Gen Z–and-younger folks, their networks are so huge online, it’s almost a blessing. You can’t figure out who their close friends are because they’re friends with everybody. It almost negates the exposure.”

Could this really be true?

“Social media is not a huge deal at all,” Burns said as we settled in across from each other at the conference table. Burns has been at the Agency more than 30 years and has the warm and amiable manner of the coach who wants to make sure everybody gets some playing time. He was very keen that I (and, by extension, all millennial and Gen Z readers of this magazine) understand that you do not need to lead a totally offline life to qualify for covert work. In fact, if you are active online, he warned, “don’t abandon your social media the minute you start working here.” (Also: Don’t do crimes and “Don’t say you work here.”)

Burns explained the application process like so: When would-be spies (a.k.a. case officers) apply for jobs, they have no idea if their role will involve covert work or not. If your application—résumé, writing samples, standard-issue government-job stuff—passes muster, you take a personality test, which is handled by in-house psychologists who make determinations about your judgment, your ability to collaborate, and other “softer skills.” If you say you speak any other languages, you’re tested on that proficiency as well.

Then comes an interview. Where do the interviews take place? “We will tell the applicant,” said Burns, meaning he wouldn’t tell me. A conditional offer of employment becomes official once you pass a security clearance, which, as the initiated know, can take up to a year—a year!—during which you can go live your life, again without committing any felonies or updating your Twitter bio to say “CIA hopeful.”

Oh, and one more thing, nota bene, which I learned from a helpful How We Hire page on the agency’s website: “For your security, if you are interested in or have applied for a job at CIA, do not follow us on social media.”

Naturally, I asked if I could take the personality test. They said no, so I guess we’ll never know if I’m too unstable for spycraft. Nor did I get to take a polygraph, which a millennial CIA analyst who joined the Agency less than five years ago told me via email was a very concerning part of the process, “especially since I applied right after college! I was nervous that the Agency wanted a certain kind of person and that I wouldn’t fit the mold.” This analyst was also a bit concerned about how they could still use social media to support certain causes without violating the Hatch Act, the law that bars federal workers from going all in on partisan activities. But after they had a sit-down with an Agency attorney to talk it out, all was well—“I just don’t post about the Agency, I don’t advocate for or against any particular political parties, and I’m extra-careful about my privacy settings.” (Side note: Though you’d think a person accustomed to being super-active on the group chat would struggle with being separated from their phone all day, this analyst assured me, “The mission is so dynamic that you’ll rarely, if ever, be bored, and the longing for your phone and social media sort of dissipates.”)

Okay, so just for the sake of argument, let’s say the Agency doesn’t mind at all that I’ve immortalized some of my tackiest Halloween costumes on Instagram and may or may not have posted the results of multiple BuzzFeed “Which Gossip Girl Character Are You?” personality quizzes on Facebook. And I, too, have made it through the recruitment process. I’m given an assignment as a case officer. Time to go undercover.

I asked Michael T. Burns: If you give me a fake name, but meanwhile I already have this whole online life where I go by my real name, can’t somebody just take my picture, reverse-Google-image-search it, and blow my cover? “We don’t give people fake names in most cases,” Burns said. “It’s just about not having an association with the Agency.”

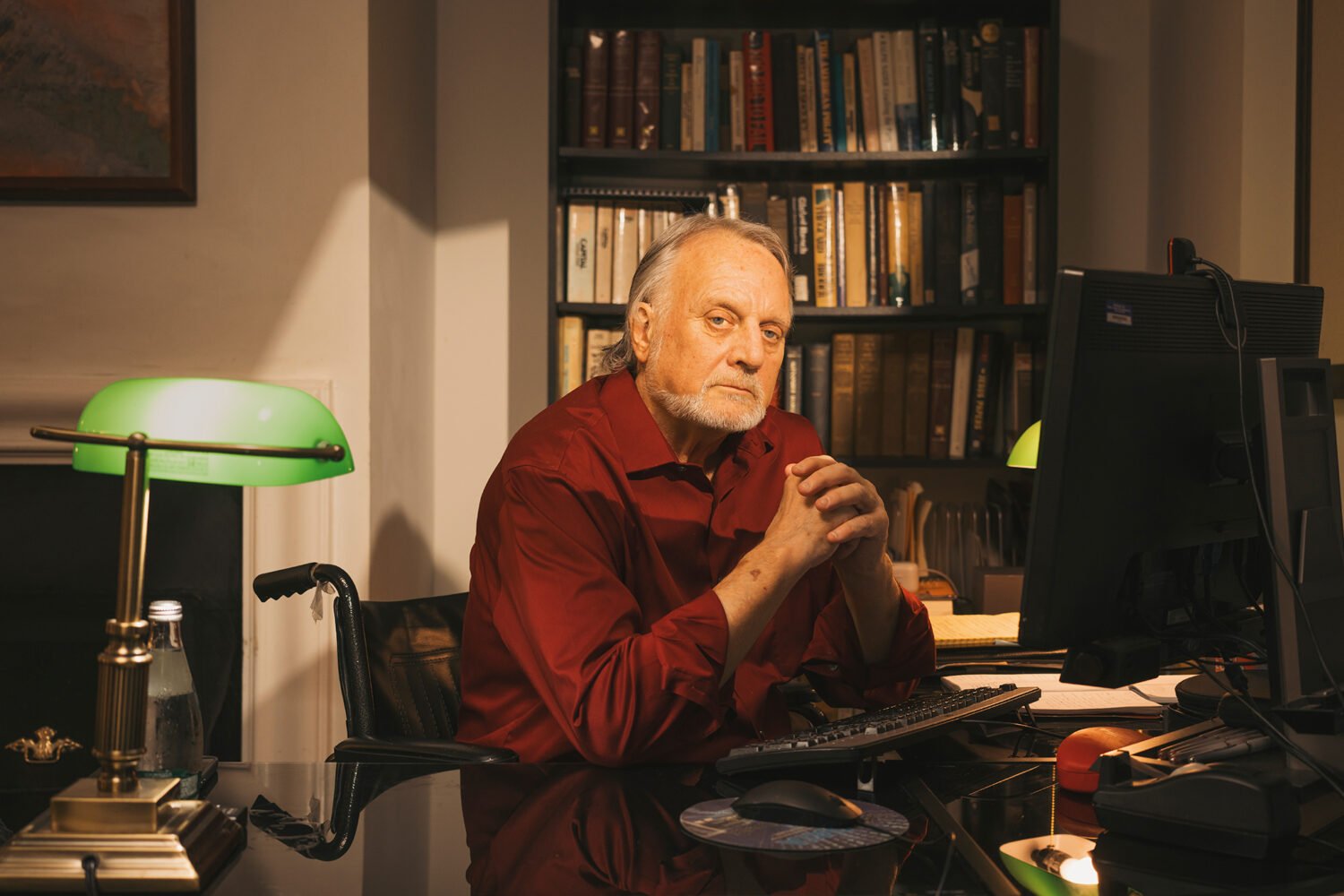

I’m disappointed not to be getting an alias and a disguise—I was hoping wigs would be involved, like maybe Keri Russell’s season-six redhead-with-bangs—but it turns out that, in spycraft as in life, the truth is the best lie. “We incorporate aliases consistent with biometric realities,” said Douglas London, a 34-year veteran of the CIA’s Clandestine Service, the elite branch that runs all of the Agency’s undercover operations.

The beauty of this system, of course, is that, were a person to go ahead and Google me, everything they’d find online would track with the cover I’ve given. The downside, so far as I can see, is that I am (apparently) holding down two rather demanding jobs.

“Cover is best tailored to reality,” London explained. “[And] you shape your own persona to suit cover. So it could actually be something you leverage—you leverage your existing profile to suit your cover requirements. So it’s absolutely not a nonstarter [to be on social media], unless there’s things on your social media that expose what might be considered weaknesses or vulnerabilities, like a party shot of you throwing down a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black. But it’s not a deal-breaker, and the smart case officer uses their public persona to their advantage to support their cover.”

There’s cover for status—e.g., saying you’re a “Foreign Service officer” to justify your presence in whatever country you’re operating in—and cover for action, which is why you’re up to what you’re up to, in the moment. London offered this example, in which I’m still a spy: “Say you’re Jessica Goldstein and you’re in Prague and you’re working for Washingtonian magazine—that’s really who you are! That’s legit. While you’re in Prague, you would be clandestinely meeting some senior official from the foreign ministry, and at the site of that meeting, if someone approaches you, you might [say], ‘Oh, I’m meeting my boyfriend—we’re going dancing,’ or ‘Yeah, we’re in this shady neighborhood because I’m trading currency outside the banks, or buying something black-market.’ . . . But your cover in status is really who you are.”

The beauty of this system, of course, is that, were a person to go ahead and Google me, everything they’d find online would track with the cover I’ve given. The downside, so far as I can see, is that I am (apparently) holding down two rather demanding jobs.

Most of the CIA’s spies are not running around telling people they’re reporters just enjoying a night out with a hot date in Holešovice. (Or are they?) My editor, for one, assures me he doesn’t have a Prague correspondent and he suspects that any half-competent enemy intelligence agency would think there’s something fishy about a Washington-area lifestyle magazine assigning someone to the Czech Republic. And I do have it on good authority that he’s right; the CIA doesn’t really like its spies to pretend being reporters. Typically, “a lot of them are going to be passing off as diplomats for the State Department,” said Andrew Hammond, historian and curator at the International Spy Museum, “so as long as there’s a digital footprint that supports that cover identity, that’s fine.”

What about the extraordinary cases in which fake identities are required? For this, I consulted the expert of all experts: Jonna Mendez, former chief of disguise in the CIA’s Office of Technical Service. (For the Bond fans out there, she was our Q.) “The fact is that we have always been using deception, whatever form it would take, to allow our operating officers to go out under false names,” she said. “The need has never changed. So many places in the world, and so many operational acts, can only be done in another identity.” What has changed is the playing field: What used to need to work only in an analog capacity now has to transfer to cyberspace as well.

Mendez theorized that there could be a way to futz with an online presence temporarily, for cover purposes: “You might want to say, ‘Maybe let’s keep the pictures, and I could rewrite my history. Here I am with some school chums, but I’m not in this state or country, I’m in that state or country.’ You probably only do that on a temporary basis, and then when you don’t need that [narrative], you flip it back to your own.”

She mentioned a mission involving her husband, fellow former CIA officer Tony Mendez, which you likely know about because he’s the guy Argo is based on and this scene is in the movie. Remember when Ben Affleck–as-Tony gives a business card with an LA phone number to an immigration officer challenging his story? And the officer dials the number and someone picks up the phone to say, “Studio 6 productions, may I help you?”

“That was called backstopping,” Mendez said. “And now . . . we transfer these capabilities into a digital world.”

She doesn’t know exactly how the CIA backstops now, and even if she did, she wouldn’t tell. But she doesn’t doubt there are ways, given the capabilities of the disguise department during her tenure, which ended in 1993. “We could do almost anything with disguise by the time I left,” she said. “We could change you into specifically another person or generally another person. We could change your gender. We could change your ethnicity. We could change your skin tone. We could change your nationality. We could turn you into anything, or we could turn you into another you, so there could be two of you if that would be useful.”

Okay, so young people who want to work at the CIA need not fear that their TikToks render them unemployable. But do young people even want to work at the CIA?

The Agency knows it has a, shall we say, image problem, with its youngest potential recruits—some of whom are younger than the war in Afghanistan and many of whom, as a cohort, are more skeptical of institutions—wary of the work the United States government and military undertake, and suspicious of the means with which they execute those missions. It’s not an unprecedented wave of antiestablishment sentiment. College students were famously among the most vocal opponents of the Agency during the Vietnam War, and the CIA responded to their criticism . . . by spying on them in what the New York Times would later reveal was a massive, illegal intelligence operation.

But this more recent skepticism and scrutiny are hitting at a time when intelligence agencies are facing intense competition from filthy-rich tech companies for future hires. Even though the CIA saw a major surge in applications in the immediate wake of September 11 (it received three times as many résumés in 2002 as it did in 2001), that fervor faded as the war on terror dragged on and reporting exposed the unsettling contours of the CIA’s tactics. A 2018 Pew study found that only 47 percent of millennials agree that the intelligence community “plays a vital role in protecting the country,” compared with 78 percent of respondents in their grandparents’ generation. According to an earlier Pew study, millennials also hold more critical views of the CIA’s post-9/11 interrogation methods, including its use of so-called black sites to hold, question, and, in some cases, torture individuals suspected of terrorism.

At the same time, the brass knows it needs to diversify the ranks. Langley was historically lousy with WASPy white guys—mostly Yalies, though Princetonians would do—who, in turn, focused their recruitment efforts on young men just like them. Only six years ago, in 2015, civil-rights activist Vernon Jordan chaired a study on diversity for then–CIA chief John Brennan, which found that “over the past twenty years—in several critical areas—the senior leadership of the CIA has become less diverse. . . . The Agency’s workforce is not diverse . . . . In fact, the more senior the Agency’s workforce is, the less diverse it is.” Demographic data from four years after that (2019), collected by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, revealed that intelligence agencies were still behind the federal and civil workforce in minority representation and that the spy agencies’ head counts were 61 percent male, 39 percent female.

Given the ever-sprawling nature of America’s intelligence missions, how can the CIA court allies and catch terrorists without case officers who can blend in anywhere and connect with people of all backgrounds and creeds? Burns, who wore a Virginia Tech lanyard around his neck during our interview (he earned his bachelor’s there), said the Agency aims to improve in this department, and he cited its outreach to historically Black colleges and universities as one example of that effort. The CIA has started bringing younger officers on college visits, too, so recruits can “see themselves” in the Agency.

Because most of us—possible future spies included—spend most of our time looking at our phones, the CIA also zhuzhed up its online presence and finally joined the rest of us on social media. In 2014, @CIA practically broke Twitter with a zinger of an introduction: “We can neither confirm nor deny that this is our first tweet.” The Agency joined Facebook, too. The feeds don’t exactly dish out Argo-style capers—it’s mostly job postings and archival bits that make for slightly better reading than a government white paper. (It has just over a million followers on Facebook and 3.2 million on Twitter.) But the @cia you see on Instagram is a little voicier and a little more personal.

Two years ago, the trio of millennials who reportedly work on that account unveiled a Humans of CIA campaign, inspired by the popular Humans of New York photo series. Pics of actual employees and officers, their faces typically shielded from view, appear alongside first-person stories about the work they do and why. It’s fairly predictable, proud-to-serve stuff, although headquarters has apparently given its blessing to some cutesier content, too. One hashtag series, #LoveAtLangley, featured stories of employees who fell in love with their fellow officers. (No lie, it was pegged to Valentine’s Day.)

Traction on the account—it’s got 406,000 followers—is just okay. The FBI has 1.9 million, and Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff has a million. Although plenty of people were paying attention this past spring when @cia released a video spot about an Agency employee named Mija who ID’d herself as “a woman of color,” “a mom,” and “a cisgender millennial who’s been diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder.” The clip was intended to showcase the inclusive nature of the CIA but was roundly mocked across the internet. “If you’re a Chinese communist, or an Iranian Mullah, or Kim Jong Un…would this scare you? We’ve come a long way from Jason Bourne,” tweeted GOP senator Ted Cruz, who apparently didn’t get the memo about the CIA being more like The Office than 24 (or else spent too much time staring at the posters in Burns’s conference room). Trevor Noah devoted a Daily Show segment to the spot, asking, “If you’re such good spies, shouldn’t you already know who you should hire?”

View this post on Instagram

Even CIA.gov got a new look. Headquarters relaunched the website this year, and it now bears all the visual signifiers of a millennial- and Gen Z–friendly organization: sans-serif font, slick new logo, and dog-training advice (presumably because some millennial-whisperer told them that puppies always do numbers online). Job listings on the site include information about starting salaries; the Agency is even posting openings on LinkedIn.

The charm offensive hasn’t won over the most progressive and extremely online young people—a typical take, from Refinery29, accused Langley of “using trendy aesthetics” to “veil what they truly operate and exist to do . . . to impose violence on both Americans and people in other countries.” But, by perhaps the most important metric, these efforts are resonating. A CIA spokesperson told me that its 2021 class is “the third-largest in a decade and represents the most diverse talent pool, including persons with disabilities, since 2010.”

Reflecting on the qualities the Agency is looking for in spies, I have to admit that even without knowing how well I’d do on the psych exam, I’m probably not the recruit they’re looking for. You’re reading this story in the only language I speak fluently. My cyber-savvy pretty much begins and ends at “Have you tried turning it off and turning it back on again?” Probably for the best to stick with the job I’ve already got.

Or maybe that’s just my cover.

This article appears in the November 2021 issue of Washingtonian.