Antonio Mugica was in his London headquarters, about a week after Election Day in 2020, when he learned that had become a central villain in Donald Trump’s Big Lie. At first, the idea seemed more preposterous than dangerous. Mugica couldn’t imagine that anyone would take seriously the notion that his election technology company, Smartmatic, had rigged the presidential race. After all, Smartmatic’s software had been used in only a single county, Los Angeles, and it had nothing to do with tabulating votes. So when the absurd claim surfaced, Mugica reassured himself: “No one is going to believe this bullshit.”

But for the agitators of MAGA fanaticism, a controversy in Smartmatic’s past had made it an ideal bogeyman. Fourteen years earlier, the administration of President George W. Bush had investigated the firm after learning that Mugica, who was born in Venezuela, had had a prior business dealing with the regime of Hugo Chávez. And in the days after the election was called for Joe Biden, Trump’s most rabid allies would twist the details of this decade-and-a-half-old kerfuffle to cast Mugica’s team as perpetrators of a diabolical plot.

Mugica and his colleagues were targeted by death threats. “The only way to resolve your interference in Western democracy,” read one such taunt, “is to shoot dead your company executives.”

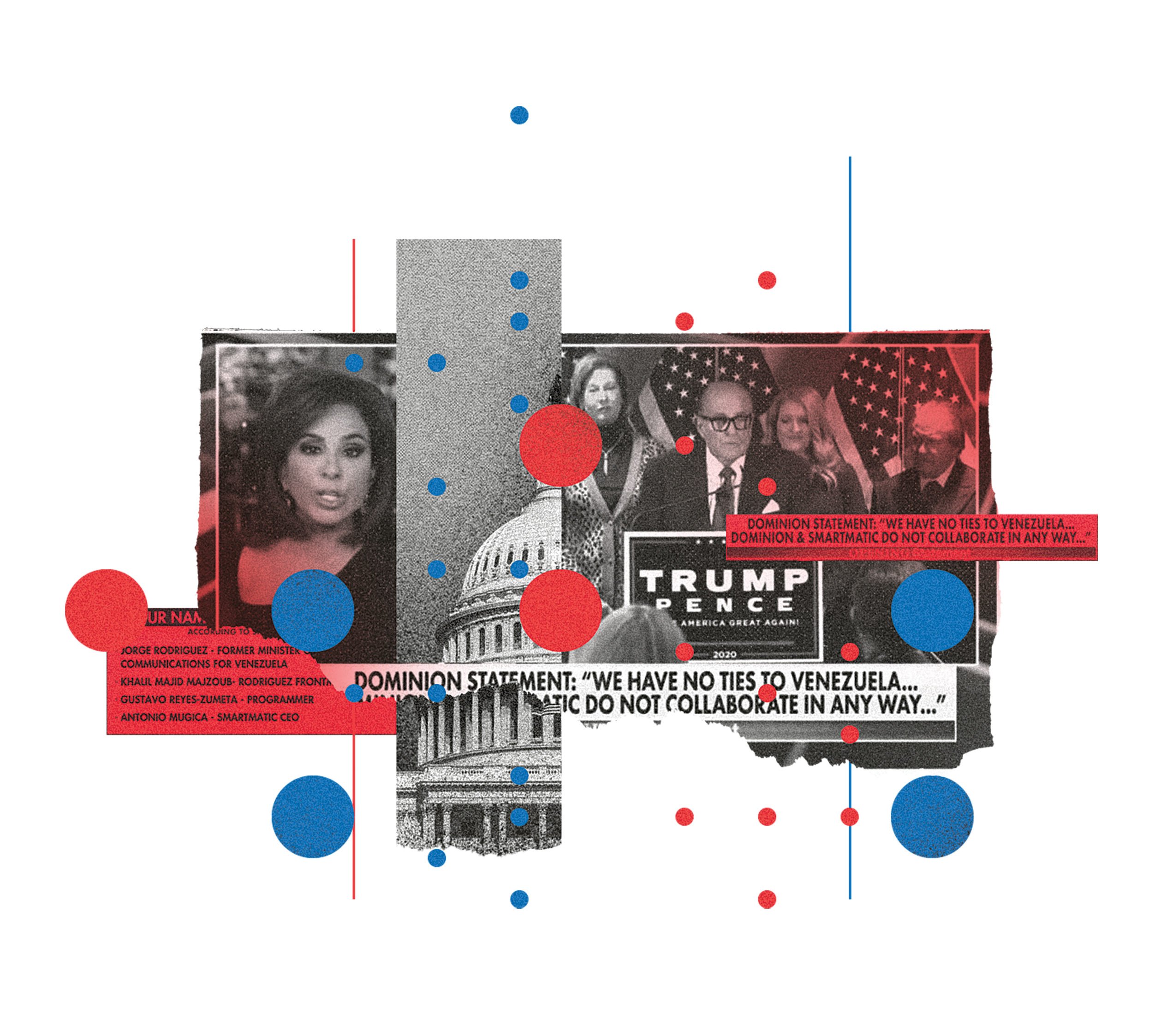

“You’re gonna be astonished when I tell you how [Smartmatic] was formed,” Rudy Giuliani told Fox Business Network’s Lou Dobbs on November 12, 2020, according to a transcript included in documents Smartmatic subsequently filed in court. “It was formed, really, by three Venezuelans, who were very close to . . . dictator, Chávez, of Venezuela. And it was formed in order to fix elections.”

Then another conspiracy theorist explained to viewers that Smartmatic’s software could be loaded onto voting machines in order to effectuate the fraud. “They can do it from Germany or Venezuela, even,” Sidney Powell, then a lawyer for the Trump campaign, said during a Fox News appearance. “We’ve identified mathematically the exact algorithms they used and plan to use from the beginning to modify the votes, in this case, to make sure Biden won.”

“We’re up to about 623 [thousand] unlawful ballots in Pennsylvania and about 320 [thousand] unlawful ballots in Michigan,” Giuliani told Fox Business Network. “This was a stolen election.”

As the delusions gained traction in the pro-Trump echo chamber, Mugica’s company slipped into chaos. Over the course of a few days, the smears managed to undercut the underpinning of Smartmatic’s business: faith in the security of its software. The firm was overwhelmed with panicked phone calls from election officials in some of the dozens of other countries that use its technology; some were so concerned that they cut ties with the company. All the while, Mugica and his colleagues were targeted by hateful messages and death threats. “The only way to resolve your interference in Western democracy,” read one such taunt, “is to shoot dead your company executives.”

In the 20 years since its founding, Smartmatic had processed roughly 5 billion votes on behalf of governments all over the world—and not once had it experienced a security breach. But in mid-November 2020, with his customers rattled and his employees frightened, Mugica convened his top lieutenants to convey the gravity of the crisis. “Look,” he told them, “this could wipe us out.”

It was then that Mugica made a decision that would turn his anonymous tech company into a high-profile cause. He hired a notoriously tough libel lawyer who, in February 2021, filed a $2.7-billion defamation lawsuit against the people and media organizations that Smartmatic considered the chief promoters of Trump’s stolen-election conspiracy, including Giuliani, Powell, Fox News, and the cable-news celebrities Lou Dobbs, Maria Bartiromo, and Jeanine Pirro—all of whom have denied defaming the company. (Smartmatic subsequently sued the far-right broadcasting outlets One America News Network and Newsmax as well as MyPillow founder Mike Lindell. OAN, Newsmax, and Lindell have denied the allegations of defamation; Newsmax has filed a counter-lawsuit against Smartmatic.) The company is actually one of two casualties of the election-rigging conspiracy theory that has turned itself into a combatant in the war on disinformation—a second target, Dominion Voting Systems, has also filed defamation complaints seeking billions of dollars in damages against Giuliani, Powell, and Fox News, among others. (All three have denied Dominion’s defamation claims.)

After the rise of QAnon and the fallout of Pizzagate, the delusions of “Stop the Steal!” and the threat to American democracy wrought by January 6, it’s only natural to wonder what crises may confront us this year as, once again, the 45th President is stirring animus and voters are preparing to cast ballots during the midterm elections. And even though the resolution of these lawsuits could still be a way off, they very well may come to represent an urgent and critical new countermeasure in the battle for truth in public discourse—a blunt weapon against the real fake news. “My sole responsibility is to do my best for Smartmatic and try to win this case for Smartmatic,” says Erik Connolly, Smartmatic’s lawyer. But, he continues, “there is a broader audience that hopes this lawsuit can send a message about disinformation being spread by news organizations and hoping that news organizations will get back to publishing the facts.”

Antonio Mugica wouldn’t have been involved in the 2020 election at all were it not for the voting debacle that had gripped America two decades earlier. Back in 2000, he was building his tech startup from the dining room of his father’s vacation house in Palm Beach County, Florida. The firm was focused on developing software that enabled physical devices to communicate with one another through online networks—technology that would come to be known as “the internet of things.” But when Palm Beach became the epicenter of the hanging-chad controversy during the 2000 presidential election, one of Mugica’s business partners suggested they change course: “You always tell me how secure our network is,” the business partner said. “Why don’t you use all of this security for a voting solution?”

Mugica had long been fascinated by the vulnerabilities of computer systems. Growing up in Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, he was enamored with the 1980s hacker flick War Games, and he eventually learned how to penetrate networks himself. “You could say I was a hacker,” he recalls. “I never did anything wrong, but I did kind of break into things and, let’s say, gain access to systems just for the sake of doing it.” After graduating from nearby Simón Bolívar University, he teamed up with two other Venezuelan nationals to form a business partnership. Hoping to land some of the venture capital that was then pouring into tech startups, he relocated the operation to Florida in 2000. Then, after the Supreme Court’s Bush v. Gore ruling, Mugica decided to take his partner’s suggestion.

It was an ideal time to enter the business. Following the chaos in Florida, Congress passed a law providing nearly $4 billion in funding for states to replace their outdated punch-card voting systems with newer technology and to make other upgrades. Some foreign nations were transitioning to electronic voting as well. Over the next nearly two decades, Smartmatic would create software and machines that enabled governments around the world to conduct a full range of election activities—casting votes, counting ballots, authenticating voters—electronically. The firm’s tools have been deployed in many Western nations (the UK, France, Italy), but they’ve proved particularly beneficial in developing countries—Bolivia, Zambia, and Sierra Leone—where prior episodes of corruption had shaken faith in the electoral process. In 2010, for instance, Smartmatic’s innovations managed to reduce, from six weeks to just two hours, the time it took for Filipinos to learn the outcome of their national elections. Public trust in the results surged, the number of protests plunged, and post-election violence declined.

Smartmatic’s American expansion proved more complicated. In 2005, the firm purchased Sequoia Voting Systems, a British-owned company with a growing footprint in the US. While the deal would eventually provide Smartmatic with an entrée into 17 states and DC, it also enmeshed the firm in controversy. One year after the merger, Sequoia ran into trouble when trying to convert the voting systems in Chicago and Cook County, Illinois, from punch-card-based to electronic, and the snags delayed the release of some local election results. Amid the foul-up, a Chicago alderman expressed alarm over the firm’s Venezuelan-born owners. “We may have stumbled across what could be [an] international conspiracy to subvert the electoral process in the United States of America,” he said.

It took a certain cable-news rabble-rouser, though, to elevate the municipal mess into a national news story. “We know what we’re dealing with,” Lou Dobbs, then working for CNN, told viewers. “And it is a dysfunctional government [Venezuela] that is trying to render our elections precisely the same.”

Hysterics aside, the spat raised legitimate questions surrounding the foreign ownership of America’s election infrastructure. Carolyn Maloney, a Democratic congresswoman from New York, was bothered by the way Sequoia’s corporate structure had been set up; its maze of holding companies and foreign trusts made it difficult to discern the firm’s ties to the Venezuela-born businessmen. “There seems to have been an obvious effort to obscure the ownership of the company,” Maloney said at the time. For its part, Smartmatic said the corporate structure had been modeled on those of similar offshore firms, such as Royal Dutch Shell.

US officials were also concerned about Mugica’s past dealings with higher-ups in his homeland. In 2004, according to media reports from around that time, Smartmatic had been part of a consortium of firms handling the recall election against Chávez. But Venezuelan officials also chose for the consortium a second company, called Bizta, whose investors included two Smartmatic cofounders and which had previously received what Venezuelan officials described as a roughly $200,000 loan from the socialist government, the New York Times reported. The loan had reportedly been secured against a 28-percent stake in Bizta, and in exchange for the financing, a Venezuelan official received a seat on Bizta’s board.

Venezuelan officials told the Times that Bizta had repaid the loan prior to the recall election—which Chávez won. At the time, Mugica explained to the Times that he didn’t recall ever meeting the Venezuelan official who sat on Bizta’s board. But the dealings were enough to convince the Bush administration in 2006 to launch an investigation into Smartmatic’s earlier acquisition of Sequoia Voting Systems. Eventually, Mugica announced plans to sell off Sequoia rather than deal with the fallout.

Over the next few years, Smartmatic focused on its overseas expansion while developing a strategy to reenter the lucrative American market. Company leaders populated the board of its subsidiary that operates in the US with former senior federal officials—Peter Neffenger, the ex–TSA director; Paul DeGregorio, former chairman of the US Election Assistance Commission—to boost its credibility in the States. And in 2016, the firm regained a foothold when Republican officials in Utah used its software for the party’s presidential caucus. Two years later, Los Angeles County awarded the firm a $282-million contract for new electronic voting devices and software.

Though it would be Smartmatic’s only US customer for the 2020 election, Mugica viewed the LA contract as a massive opportunity. It was, after all, the largest—and perhaps most complex—voting jurisdiction in the country. If everything went smoothly there, Smartmatic could leverage the success to expand into other territory.

In LA, November 3, 2020, transpired just as Mugica had hoped. The county’s new Smartmatic-powered voting system encountered no major hiccups as it processed nearly 4.3 million ballots. The distribution of votes—71 percent of which went to Biden, 27 percent to Trump—was nearly identical to the results from four years earlier. “Actually, it was like a very boring day,” recalls Roger Piñate, one of Smartmatic’s cofounders. In the election-technology business, as Piñate puts it, “boring is good.”

By November 12, the script had flipped. Giuliani was floating the Smartmatic conspiracy on Fox Business Network. And in the weeks that followed, as the Big Lie gained traction, he and other Trump loyalists made Smartmatic the linchpin of their delusional conspiracy.

According to transcripts included in Smartmatic’s court filings, the Trumpers huffed out lies about its origins. (“[Smartmatic is] a company that was founded by Chávez, and by Chávez’s two allies, who still own it,” Giuliani said on Fox News.) They sought to link it to MAGA bugaboos. (“We know that $400 million of money came into Smartmatic from China only a few weeks before the election,” Sidney Powell told Fox Business Network, “that there are George Soros connections to this entire endeavor.”) They said the firm was corrupt, building software that’s “designed to rig elections” (Powell) and deploying “tried-and-true methods for fixing elections” (Giuliani).

“It can set and run an algorithm,” as Powell put it, “to take a certain percentage of votes from President Trump and flip them to President Biden, which we might never have uncovered, had the votes for President Trump not been so overwhelming in so many of these states that it broke the algorithm that had been plugged into the system.”

After listening to Giuliani spread the conspiracy theory on a Fox Business Network program, Lou Dobbs—who had been instrumental in elevating the Sequoia/Smartmatic controversy 14 years earlier—described an even farther-reaching plot. “This looks to me,” he said on his Fox Business Network show one night, “like it’s the end of what has been a four-and-a-half . . . year-long effort to overthrow the President of the United States.”

As the MAGA extremists trained their megaphones on Mugica’s firm, he and his colleagues were inundated with hate. Anonymous emails and phone messages menaced everyone from rank-and-file employees to the teenage son of one of the company’s executives.

“God sees what you are doing and in the end you will have to answer for your sins.”

“Location acquired. . . . Here we come.”

“What’s it like to live in fear?”

At one point, a package arrived at the company’s office in Los Angeles. Inside the parcel, employees discovered photographs of mangled human remains, according to the Financial Times. “This will be you next,” read the note.

While he increased security at Smartmatic’s offices and worked to calm frightened employees, Mugica faced a more fundamental concern. The vote-rigging conspiracy threatened to chase away his current customers, scare off future clients, and drive the firm out of business. “Because,” he says, “in the end, what we’re selling around the world is trust.”

Defamation suits won’t be enough to redress the structural and cultural forces that continue to sustain viral conspiracies like the Big Lie.

Seeing no other way to protect his company, Mugica began searching the internet for a few good litigators. One name stood out: Erik Connolly.

Three years earlier, the Chicago lawyer had won the biggest media defamation settlement in the country’s history. It was a whopper of a case, against ABC News—Connolly secured a settlement of a reported $177 million or more for his client, Beef Products Inc., after the network had repeatedly described the company’s meat as “pink slime.”

When he was first contacted by Smartmatic, Connolly spent an hour or so clicking through the coverage. Through his initial and subsequent research, he identified three overarching factual assertions the Trumpers had made, which he would later spell out in court documents: One, Smartmatic was under the control of the Venezuelan government; two, its election technology had been used in many of the most closely contested US states; three, it had switched votes from Trump to Biden in order to rig the outcome.

“Those are three core facts that are very easy for me to demonstrate aren’t true,” Connolly says. “And so, based on that set of facts, it seemed like they would be able to have a very strong case.”

Connolly and a team of eight attorneys spent several weeks sifting through news clips and social-media posts to identify specific lies—they eventually flagged more than 100 claims that they considered false and misleading—and trace them back to their sources.

In December 2020, he fired off letters to Fox News, OAN, and Newsmax demanding that they retract prior false statements about his client. But Connolly and Mugica soon concluded that there was only one way to repair the financial damage and recover the firm’s reputation: Expose the big lie about the Big Lie. “You get a jury saying what these people said about this company wasn’t true,” Connolly says. “And we are telling the world that.”

Defamation cases are notoriously difficult to win. And Mugica’s firm is after an extraordinarily large judgment: $2.7 billion. That’s the minimum amount of financial damages it says it incurred as a result of the smears. (The second target of the conspiracy theory, Dominion, is suing Fox News, Powell, and Giuliani for $4.2 billion. All three have denied Dominion’s defamation claims.)

Courts tend to weigh free-speech rights carefully. And not surprisingly, Paul Clement—the Washington superlawyer who’s representing Fox News and its current and former hosts in this case—has put forth a First Amendment defense. “Smartmatic’s 285-page, $2.7 billion complaint is not just meritless,” Clement and other lawyers said in a court filing on behalf of Maria Bartiromo, “it is a legal shakedown designed to chill speech and punish reporting on issues that cut to the heart of our democracy.”

The argument of Clement and Fox News’s other attorneys goes like this: Trump’s effort to overturn the 2020 election results was a news event of enormous consequence. And Fox Corp.’s networks and current and former hosts were simply covering this event and providing a forum for Trump’s surrogates—such as Giuliani and Powell—to back up their allegations that Smartmatic had rigged the election. “If those surrogates fabricated evidence or told lies with actual malice, then a defamation action may lie against them,” Fox News argued in court documents, “but not against the media that covered their allegations and allowed them to try to substantiate them.”

“Smartmatic’s $2.7 billion complaint is not just meritless,” Clement and other lawyers said in a court filing on behalf of Maria Bartiromo, “it is a legal shakedown designed to chill speech and punish reporting on issues that cut to the heart of our democracy.”

For their parts, lawyers for Powell and Giuliani have argued in court documents that the claims against them should be dismissed under New York’s anti-SLAPP statute, which offers protection against frivolous lawsuits involving speech in a “public forum in connection with an issue of public interest.” (Neither lawyer responded to Washingtonian’s requests for comment on Smartmatic’s legal complaint.)

At the same time, the lawyers for Giuliani, Powell, Fox Corp., and its current and former hosts have also added an interesting wrinkle to their defenses. In most defamation cases, plaintiffs must prove only that the published statements about them were false, harmful assertions of fact that were made negligently. In this case, the lawyers have all argued that Smartmatic isn’t a private entity but rather a public figure. If the judge agrees, Smartmatic would be forced to clear a much higher legal threshold; the company would have to prove that the election-related smears had been made with “actual malice”—or, as the Supreme Court has said, “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

On this point, the defendants are likely to prevail, says University of Missouri School of Law dean Lyrissa Lidsky, because Smartmatic voluntarily chose to engage in a business—helping governments run elections—that warrants a high level of scrutiny. “If I were the judge,” she says, “I would pronounce them a public figure.”

Even so, Lidsky believes that Mugica and Smartmatic have a credible claim. She explains it this way: The defendants would have known that the conspiracy theory wasn’t true if they had bothered to conduct a simple Google search; after all, Smartmatic played no role in the election outside of Los Angeles County. Should the case proceed into discovery, Connolly and his team could very well unearth damaging emails and other internal materials showing exactly what the pro-Trump flamethrowers may have known to be false before they went on television to broadcast their lies. “It’s hard to prove actual malice,” Lidsky says, “but this is the rare case in which it looks at the outset like there’s a pretty decent chance the plaintiffs can do it.”

In legal filings, lawyers for Giuliani, Powell, Fox Corp., and its current and former hosts have disputed this notion, insisting that none of the defendants acted with actual malice.

Last August, the two sides met virtually for a hearing on a Fox News motion to dismiss the case. David Cohen, the New York state judge presiding over the matter, seemed skeptical. During oral arguments, he referenced a false statement made on the air by Lou Dobbs: that Smartmatic’s technology had been banned in Texas prior to the 2020 election. “How is that not defamatory?” Cohen inquired, according to CNBC.com.

In the roughly 15 months since Connolly teamed up with Smartmatic, there have been a number of developments inside the right-wing media ecosystem. In December 2020, after Connolly sent his initial cease-and-desist letters, a Newsmax host read a facts-clarifying statement from the far-right media outlet on the air, saying: “No evidence has been offered that Dominion or Smartmatic used software or reprogrammed software that manipulated votes in the 2020 election.” In February 2021, 24 hours after Smartmatic’s lawsuit landed, Dobbs’s show was canceled, a move Fox News described as part of previously planned changes. And last summer, when Fox broadcast a live speech by Donald Trump in which he continued to spread the Big Lie, the network also aired a disclaimer that read: “The voting system companies have denied the various allegations made by President Trump and his counsel regarding the 2020 election.”

But the pro-Trump networks and broadcasters have billions of reasons (literally) to be concerned about Smartmatic’s lawsuit. “The damages,” Lidsky says, “could be ruinous for some of these people, some of these media organizations.”

For those who revile Trump and the far-right media world he feeds—and for the left flank of American politics already on edge about 2024—there’s a cautionary note here, though. “[Litigation is] part of an agenda for addressing misinformation and disinformation and outright lies,” says Timothy Zick, a professor at William & Mary Law School. “But it’s a really inefficient one.” Defamation suits are extremely expensive and time-consuming to bring—they won’t be enough to redress the structural and cultural forces that continue to sustain viral conspiracies like the Big Lie.

Nevertheless, in early March, Smartmatic got some encouraging news. Judge Cohen dismissed all claims against two of the defendants: Pirro, because her comments in question hadn’t targeted the voting-technology firm, and Powell, for issues related to jurisdiction. Powell’s attorney, Howard Kleinhendler, told Washingtonian that his client believes the judge was correct to dismiss the claims against her. But the judge allowed the lawsuit against Fox News, Dobbs, and Bartiromo to move forward. “Even assuming that Fox News did not intentionally allow this false narrative to be broadcasted,” the judge concluded, “there is a substantial basis for plaintiffs’ claim that, at a minimum, Fox News turned a blind eye to a litany of outrageous claims about plaintiffs, unprecedented in the history of American elections, so inherently improbable that it evinced a reckless disregard for the truth.” The ruling against Giuliani was split; the judge dismissed some of the claims against him and allowed others to proceed.

Fox, for its part, plans to immediately appeal the ruling and file a counterclaim under New York’s anti-SLAPP law. “The trial court has already dismissed the claims against Jeanine Pirro, and we firmly believe that in subsequent proceedings the claims against Maria Bartiromo, Lou Dobbs and the Fox defendants will suffer the same fate, and that Smartmatic’s damages claims will be exposed as wholly unsubstantiated,” Clement said in a statement. “The First Amendment stakes in this lawsuit could not be higher, as allegations about the integrity of a presidential election leveled by lawyers for the sitting President are inherently newsworthy.”

This article appears in the April 2022 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)